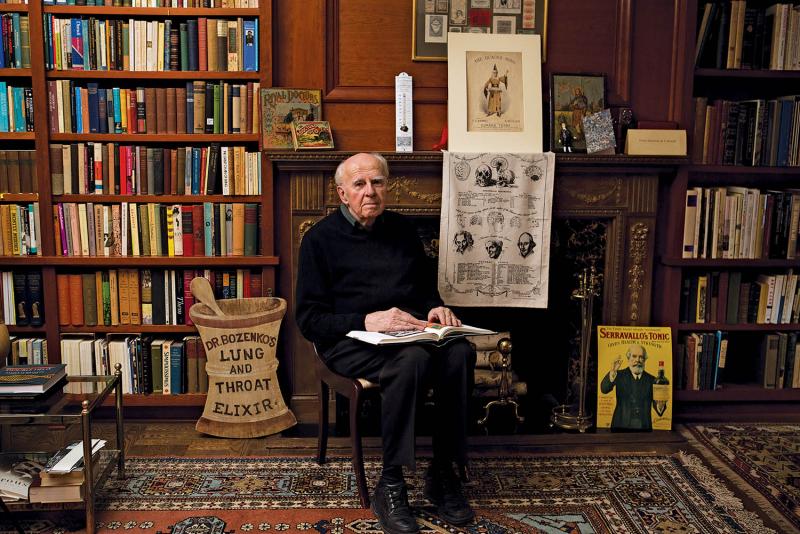

On September 23, 2014, William Helfand joined Jack Hitt onstage at the Institute Library in New Haven, Connecticut, as part of the ongoing series “Amateur Hour,” in which various tinkerers, zealots, and collectors discuss their obsessions. Helfand, whose interest in quackery began as a hobby while he was employed at the pharmaceutical firm Merck & Co., has amassed what is arguably the greatest collection of quackery art and ephemera in the world. Much of his collection is now housed at the Library Company of Philadelphia as well as the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Yale Medical School Library. The conversation that follows was recorded live and has been edited for brevity and meaning.

Jack Hitt: Bill, what exactly is a quack?

Bill Helfand: Well, example A would be a man named James Morison, who did a lot of advertising for his pills in England in the 1830s and 1840s. He developed his product because, he said, he became ill and nobody could cure him. He devised a theory—that there was only one disease, really, and that one disease was impure blood, and the way to treat it was with vegetable drugs. And so he created Morison’s Universal Vegetable Pills. For years, they were sold in America and all over Europe. He made only two different strengths: Morison’s Pills Number 1, and Morison’s Pills Number 2.

What were they?

The pills were laxatives, and with his one theory, he claimed he could cure anything. He could cure smallpox. He could cure cancer.

Didn’t people realize that the pills didn’t work after taking one?

Morison said that if one won’t work, take two. And if two won’t work, take four, and so on. I became interested in Morison basically because of all the caricatures cartoonists had made of him. But he published wonderful ones himself. One was entitled “Medical Confessions of Medical Murder.” Morison often inveighed against the evils that medicine would bring—in advertisements he called it “the guinea trade,” that is, regular doctors would charge you in guineas. Take Morison’s pills—you’ll get better no matter what you have.

I think many of us have this impression that quackery is this one brief moment, largely in America, that happened in the nineteenth century.

Quackery has always been with us. There are many images of the quack coming to a small town dating back to the sixteenth century. Quackery is not the oldest profession. We know what is the oldest profession. But it’s probably the second-oldest profession. It was one of the easiest things to get into because all you had to do was say my product cures some serious disease, and you did not have to back it up.

It was that easy?

A quack may have had the ability to read and understand and might well have known as much as many physicians would have known—at least up through most of the nineteenth century.

So, for a while it was hard to tell the difference?

James Boswell went to quacks as well as orthodox physicians. You went to a regular physician for whatever ailed you, except maybe a venereal disease. You didn’t particularly want him to know that you’d caught a venereal disease or word would get around. So you went to a quack, who made a living of offering panaceas for all kinds of venereal disease.

And of course the standard treatment for syphilis in those days was mercury.

Which was effective, but the side effects—mercury poisoning—were almost as bad as the venereal disease itself. You lost your teeth. You smelled bad no matter where you went. When the New World was found, one of the first medicines to be imported back to Europe was guaiac, where they felt the resin from trees would be a cure for venereal disease, but it was not that effective. Nothing beat mercury until penicillin came out, which was a godsend.

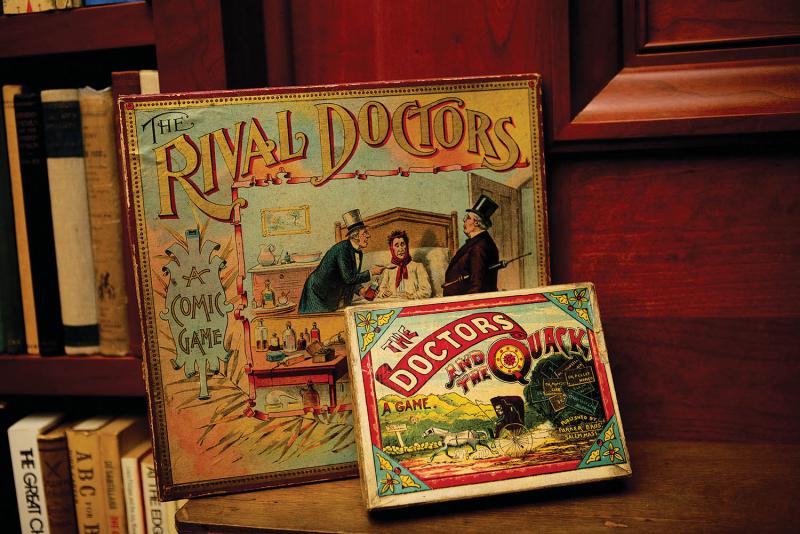

And quacks were regular figures in the popular culture of that time?

Absolutely. James Gillray was among the best caricaturists in what was the golden age of caricatures in Great Britain—the late eighteenth, early nineteenth century. One of his more famous images shows John Bull—then the political cartoon stand-in for all of Great Britain—being treated by a quack doctor with metallic tractors—three-inch-long, pointed metal rods, which were applied to an area of inflammation. They would supposedly draw out poisonous electrical fluids and cure the ailment. Of course they didn’t work. There was no reason behind them. The inventor was an American named Elisha Perkins, and he did fairly well with selling them and sent his son over to England to develop a market for them. And while in England it was proven to be a fraud.

So the metallic tractors literally just touch someone’s inflammation or face or whatever—

Yes, just touch.

It wasn’t even acupuncture or something?

No, just touch. Pure quackery.

So a true quack could make a medicine or a therapy out of almost anything?

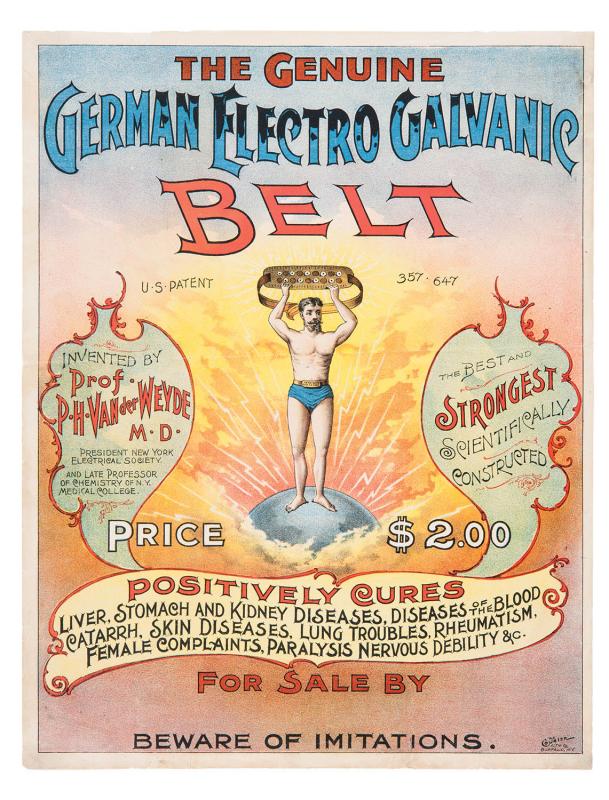

People who made medicines out of thin air liked to take advantage of every new discovery that came along. If all of a sudden we discovered radioactivity, radioactivity would become a cure for rheumatism.

They did that?

Take electricity. When it was invented, people made electro-galvanic belts, prescribed them, and advertised them profusely. They made electric shirts, electric shoes, electric everything. And of course, it was inconceivable that these inventions wouldn’t have an effect. They had to have some effect. And they did, because the electrodes were made with copper and tin, and when the body sweat against them, you could feel a tingle: Hey, this thing is working! It’s like Morison’s Pills, which were laxatives. Of course they worked.

You could tell it worked! But what you’re also saying is that many people couldn’t tell the difference between the efficacy of Western medicine and quackery.

Up until maybe three-quarters through the nineteenth century, let’s say 1875, I think you stood just as good a chance of going to a quack for your illness as to an authentic physician. After that, medicine kept growing and improving, and knowledge of diseases, what caused them and what could help cure them, improved. It’s at your peril that you go today.

Many are still with us?

Well, there are questionable areas, homeopathy being one, wherein the cure involves the minutest amount of medication. One teaspoon falling into the Atlantic Ocean is too strong. Many people do believe in it. Some people think acupuncture is great, and in many cases it is great and many cases not. In the early nineteenth century, Samuel Thomson felt that a plant called lobelia had in it some effective ingredients that would cure most diseases—just heat and lobelia alone. And he developed his theories for curing a lot of types of illness and became extremely popular. There were shops specializing in “Thomsonian medicines.” Thomsonian almanacs existed. Americans strongly believed in water—using internal water and external baths, cold baths, hot baths—to cure various diseases. Europeans still believe in the water cure. Baden-Baden. If you’re French, you can get a physician to prescribe several weeks of cure in Vichy.

So, was American quackery any different from Old World bunkum?

I don’t think so. We had a frontier mentality for a long time. For many years there were parts of the country where there was no reasonable medical help that you could get to come to the house if you broke a leg. The physician would be pretty far away in many cases. So the vendors of medical aids, the people who were the colporteurs from Europe, came and developed routes throughout the country, through places that didn’t have large populations. And the housewife would buy medicines from them, and this sprung up some purely American ways of doing business with these products, one of which became known as the American medicine show.

Was there more than one?

There were many, like the Kickapoo Indian Medicine Show. They hired white people who darkened their faces to become Indians. There were many Indian medicines because, in those days, people would say, “Did you ever see a sick Indian?”

Was there any one great impresario of the medicine show?

Well, Clark Stanley was a real person and he was famous for his remedy: Clark Stanley’s Snake Oil Liniment. He used to appear at county fairs and medicine shows and have a stand. He would get a crowd around him, bring out his snake and chop the snake’s head off and cut out the tallow from underneath the skin of the snake and describe how he made the snake oil, and then he’d sell the package. You can see from the advertisement that it was good for many things, which is one of the key methods of recognizing a quack. When you’ve got too many things that it will cure, there is something wrong. Nothing cures that many things—except Morison’s Pills.

There was no truth in advertising back then.

Which is probably why the slogan on the side of the box says, “Good for everything a liniment should be good for.”

But it wasn’t just medicine, it was a show.

They used to come out and start with somebody who would entertain the crowd and get them in a good mood: musicians, singers, dancers, comedians. Much of television, in some ways, is just an offshoot of the great American medicine show. Some of the comedians in Hollywood—Danny Kaye, for example—worked the medicine-show circuit. And once the entertainers in a medicine show got the audience warmed up, they’d hand it over to the quack. He would make his spiel for the product he was selling, and they often had an entire line of products they would sell. I’ll give you one story. Many years ago, the Smithsonian Institution invited the people who were the docs selling the medicine as well as the entertainers to Washington to talk about their experiences working in the medicine show.

Retired quacks?

Yeah. These were quacks who had worked the circuit. The Smithsonian had these people come out on the Mall and go through their spiel, what they used to sell the product. One remains fresh in my mind, one of the older surviving quacks, a man named Doc Milton Bartok. During the Depression years, he worked out of storefronts in large cities, where he set up and he would sell his medicines. And so Doc Bartok was there, and he drew a crowd around him talking about his product. He started off with a visual aid, a view of the inside of the body, and he said—and I try to remember him as best I can—“My product is not for everything. It is only for problems of the liver, the kidney, and the bowels. Now let me just show you what happens when you eat some food.” And he would point to the large intestine, then to the small intestine. And he’d show how the small intestine is composed of an ascending colon, a transverse colon, and a descending colon. And he said, “The food in the body comes in and it goes up the ascending colon, over the transverse colon, and down the other. But you may well ask, ‘How on Earth does the food go up the ascending colon? What drives it up?’ Well, let me tell you, God in his wisdom has placed a little sack on the bottom of that ascending colon called the appendix, and every once in a while it squirts the food up. It pushes it up.”

Science!

I raised my hand. “Hey, hey, doc, where did you learn that? Was it a book? Did somebody teach you? School? Where did you learn it?” And he said, “Well, ya see,” and then he goes rambling on into some other field. I said, “No, no. I’ve asked you a specific question. Where did you learn that? Where did you get that information from? What magazine? What textbook?” He said, “Well I’ve studied hard.” I raised my hand a third time: “Where did you get that from?” He said: “I made it up.”

When I was reading about quackery, I saw that the flea circus, freak shows, and even the amateur hour were often features of the traveling medicine show.

Many personalities in the entertainment world came out of that milieu.

I’m curious about your connecting the medicine show with TV.

Well, the modern infomercial is quackery in its pure form. It’s whatever they can get away with at 4 a.m. Just to watch what they do and what they can get away with. It’s remarkable—I mean, I feel cleansed by just listening.

One of the things that I was reading mentioned that, toward the end of the nineteenth century, these quack medicines were using really potent drugs. Like, we were teething children with cocaine and opiates.

In the nineteenth century you could put cocaine into a product without saying it’s cocaine. Vin Mariani did that. It was sold as a “tonic wine” that “fortifies and refreshes body & brain.”

Who sold it?

Angelo Mariani was an Italian pharmacist who moved to France to work, and he was a master at advertising. Even in the 1870s. He developed a product called Mariani Wine in English or Vin Mariani in French. He imported the leaves of the coca plant, which grow high up in Peru, and he steeped them in Bordeaux wine. He would say in his advertising that only select grapes make the wine that is in Vin Mariani. You can’t make it from any old grape. So he made Vin Mariani, and it contained cocaine, obviously, from the leaves.

How was he a master at advertising it?

He would send a case of it to important people throughout the world. He sent it to the Pope. And the Pope would get the case of this stuff, and then dictate a thank-you note to Mariani. Mariani would take an engraving of the Pope, along with a copy of his letter, and he published these in annual volumes called the Album Mariani. Each contained a hundred biographies, or advertisements. I think it published for fourteen volumes.

Who else did he rope in?

President McKinley. Thomas Edison was in it. Sarah Bernhardt.

Right. So did they have any idea that they were going to be turned around and used to hawk his wine?

They may have. It became a bestseller. Coca-Cola is based upon it, using soda water.

Let me get this straight. The cocaine was okay in America, but the wine—that’s over the line. When did all this change?

They took the cocaine out before the Pure Food and Drug Act was passed in 1906. In fact, a lot of this changed after the passage of that law.

That actually marks the end of the Quack Era, right?

No, there’s no end to the Quack Era.

Well, okay, not the end of quackery, but the end of its siglo de oro.

There was an end to people getting away with everything that they got away with before. There’s a lot less of it. But, like I said, turn on any television. When I was a younger man, I eventually started going around giving talks to women’s groups and church groups and synagogue groups about the evils of quackery. Eventually that led me to find out if I could become a quack myself.

You formally enrolled in a quack school?

My alma mater is called the Anglo-American Institute for Drugless Therapy. It was in Bournemouth, England, at the time. They gave courses in osteopathy and naturopathy. I even got a scholarship to study there, and am today a licensed naturopath. My diploma has three different colors and a golden seal.

You showed me your class notes, and I was particularly taken by the lecture on ethics.

A very loose use of that word, considering.

The professor seemed to know more about Andrew Carnegie than Hippocrates. He advised that you keep the patient—and here I’m reading from your notes—“seated in a chair facing you and in the light. The patient’s chair should be hard, of a straight-back type while your own should be quite comfortable in nature and of a slightly higher plane. This necessitates the patient lifting his thoughts to yours.” That’s beautiful.

By the way, I recently Googled my alma mater and I found that it does not exist.

To graduate you had to write a thesis paper, which I have here. You politely discuss three of the leading fields of quack nonsense of your day.

Zone therapy, which involved reading the bottom of the foot.

And iridiagnosis.

Where you look at the imperfections of the iris and determine all kinds of health issues.

A kind of ocular palmistry. The third one involved a machine?

Yes. Radionics came with a box that had wires and dials. It was 1965. People were amazed by IBM. The idea was that all matter exists in a state of vibration and that every part of the body has its own frequency. This machine was invented by a physician, Albert Abrams from San Francisco. You could put anything in there—nail clippings, hair, sweat. Twist the dials and make a diagnosis! If you leased one of Abrams’s radionic vibrational diagnostic-and-treatment machines, there was only one requirement: You had to sign a waiver that you would never open up the machine to see what was inside.

But, to earn a degree, you had to invent your own entire field of quackery. So let me read from your thesis: “This new thesis, or hypothesis, should be known as the areola or areolar method of diagnosis. It uses the nipple and the area surrounding it on the site, on which various diagnoses of illness should be made.” This is genius. “The variables that enter into differences are many, the diameter of the nipple itself, the outside diameter of the edge of the areola, the height of the nipple, and its pigmentation.”

Male genius peaks, they say, in one’s thirties.

I am sad to say that I have checked, and the science of nipples never took off. Baffling, really. In your thesis, you conclude, “I feel that the areola hypothesis has a great future. I feel that in years to come it will create a quartet of diagnostic procedures as the backbone of the diagnostic armamentarium of the naturopath.”

I’m rather proud of that sentence.