How can language serve in the face of staggering violence? In Requiem, her poem cycle that bears witness to the Soviet Great Terror, Anna Akhmatova renders a striking scene. The poet, whose son had been taken by the KGB, waits with other women outside Leningrad Prison. They are hoping to catch a glimpse of their loved ones.

How can language serve in the face of staggering violence? In Requiem, her poem cycle that bears witness to the Soviet Great Terror, Anna Akhmatova renders a striking scene. The poet, whose son had been taken by the KGB, waits with other women outside Leningrad Prison. They are hoping to catch a glimpse of their loved ones.

On that occasion there was a woman standing behind me,

her lips blue with cold, who, of course, had never in

her life heard my name. Jolted out of the torpor

characteristic of all of us, she said into my ear

(everyone whispered there)—“Could one ever describe

this?’ And I answered—“I can.” It was then that

something like a smile slid across what had previously

been just a face.

These lines came back to me as I made my way through Masha Gessen’s work in preparation for this interview. In her 2017 article “The Autocrat’s Language,” published in the New York Review of Books, Gessen outlines a relationship between the health of language and the possibilities of social change: “When something cannot be described, it does not become a fact of shared reality.” From her reporting on the war in Chechnya to her historical account of “Hitler’s War and Stalin’s Peace” told through her grandmothers’ lives to her writing on the risks and repressions of the current US government, Gessen refuses those lenses of nationalism, totalitarianism, and autocracy that distort language in service of consolidating power. Amid attacks on language—which preempt and justify other violences—Gessen’s careful looking and precise naming has often offered a common place to be, a way to imagine otherwise.

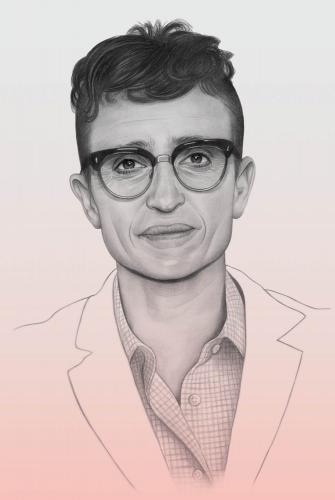

Born into a Jewish family in Moscow, Masha Gessen immigrated to the United States as a teenager. At seventeen, she began reporting for a gay newspaper in Boston. Between 1984 and 1992, Gessen covered the AIDS crisis, distilling and amplifying information in the context of deliberate government confusion and opacity. In 1991, Gessen returned to the Soviet Union on a magazine assignment. She stayed for twenty-two years, building a life as a journalist and activist. Following the 2012 protests, Putin capitalized on the efficacy of queer-baiting protestors and began a systematic anti-gay campaign. Gessen—who had been the first openly gay public figure in Russia and a vocal opponent of Putin—received pointed threats against her family. In 2013, she returned to the United States.

Gessen is the author of eleven books, including The Man Without a Face: The Unlikely Rise of Vladimir Putin (2012), Words Will Break Cement: The Passion of Pussy Riot (2014), and The Future is History: How Totalitarianism Reclaimed Russia (2017), which won the National Book Award for Nonfiction. The recipient of numerous awards, including a Guggenheim Fellowship and a Carnegie Fellowship, Gessen is a staff writer at the New Yorker and the John J. McCloy Professor of American Institutions and International Diplomacy at Amherst College.

We spoke in May at a café in Manhattan’s West Village.

Editor’s Note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Claire Schwartz: According to the poet Marie Howe, who studied with Joseph Brodsky at Columbia, Brodsky said: “You Americans are so naïve. You think evil is going to come into your houses wearing big black boots. It doesn’t come like that. Look at the language. It begins in the language.” You’ve written about the relationship between language and the social imagination—in particular, about the ways that totalitarian regimes in Russia and, more recently, the current government in the United States, have eroded public speech. Would you describe what you mean by that and how you see language functioning in public space right now?

Masha Gessen: For totalitarian regimes, language is an instrument of subjugation. It’s a way of controlling both behavior and thought. Attempting to ensure that words mean what the regime says they mean is a way of undermining people’s ability to inhabit a shared reality outside of what the regime says reality is. There are all sorts of tricks the regime performs along the way—such as using a word to mean its opposite, or almost its opposite.

I’ll give you an example. Just after the Russian Revolution, the Soviet Union mobilized the language of internationalism. But internationalism in the context of early Soviet Russia didn’t have anything to do with internationalism. In a sense, it was the opposite of internationalism; it was a new kind of empire-building. It was empire-building based on ideas of ethnic sovereignty, self-determination—where every ethnic group was supposed to have its own education system, its own literature, its own land—with porous borders, but nonetheless borders. If an ethnic group didn’t have a written language, one was going to be created for it.

Then, in the mid-1930s, official policy changed from internationalism to the Friendship of Peoples. Friendship of Peoples was actually a much more exclusively imperial project in which—though lip service was still paid to ethnic self-determination—ethnic self-determination was basically frozen at the level at which it had been in 1934. There was a great expression that went along with Friendship of Peoples: The Russian people were “first among equals.” (This was ten years before Animal Farm: “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.”) That meant that ethnic Russians would have key posts in every ostensibly national government throughout the Soviet Empire. So, that’s an example of how not only is language used to undermine a sense of reality, but language is used to undermine itself, further undermining a sense of reality. That’s a key instrument of the totalitarian state.

I don’t think that’s what’s happening now in America. I don’t think Trump could build a totalitarian regime if he tried. But he has such strong instincts that if he could, he would. It’s not for nothing that The Origins of Totalitarianism has been flying off the shelves. So, thinking about totalitarianism helps to think about Trump. He has this instinct for using language to undermine reality. It’s not just the lies. It’s when he says, “This is going to mean what I say it means.” That’s when it gets really creepy.

How does this totalitarian manipulation of language diminish our ability to envision—and therefore to enact—political change?

There’s only so much language available to us at any given time. If words are taken out of circulation, that undermines our ability to communicate. Without our ability to communicate, we can’t inhabit a shared reality. That’s what we do, right? We tell each other what we see and how we see things and what we see ourselves doing at any given time. That becomes our reality.

With fewer words, we have fewer tools for constructing our reality. It’s like: Can you build a house without a table saw? Probably. Can you build a house without a hammer? I don’t know about that. Can you build a house without a hammer or nails? No. If Trump has undermined the number forty-five, we can probably do without it. But if he manages to rid the language of superlatives altogether, it’s going to make things more difficult. That’s an actual risk.

The Soviet Union followed by Putinism managed to render words like democracy, citizenship, society practically inoperative. I think we are having a really hard time with politics. If we define politics as the process of figuring out how to inhabit the world together—that’s what politics is—then when people say, “Oh, that’s just politics,” they are using the word to mean its opposite. If you use the word politics solely to refer to electoral politics and then you do such violence to electoral politics that it becomes the opposite of what it’s supposed to mean, then the word politics becomes unusable.

You’ve pointed out that totalitarian ideologies are hermetically sealed. They work to make an outside unthinkable, uninhabitable. It strikes me that throughout your work, there is a robust sense of outsiderness—which, as a reader, I experience as the ongoing possibility of another way. How has this concept of the outside functioned for you?

There’s a very basic outsiderness. I write in a language that I speak with an accent. New York City is the only place in the world where I’m able to blend in. When I was a younger reporter, I used to fade into the background. That was different from blending in, but I could minimize my presence. Physically I don’t take up a lot of room, so as long as I kept my mouth shut, I could sit there quietly and render myself like a piece of furniture. Other than that, I’ve always stuck out. So, it’s not like I had much of a choice about writing from an outside perspective.

Also, nothing is exactly normal for me. I immigrated to this country when I was a teenager. That’s a dislocating enough experience that it precludes naturalizing the world around me. Nothing is taken for granted. That’s not always a great way to live. People naturalize things because that’s what makes the world a comfortable place to inhabit. But anything that’s uncomfortable to inhabit is interesting to describe. I find the world endlessly interesting to describe because none of it, for me, was always there and will always be.

Totalitarianism mines stability. Totalitarian regimes set out this idea of an imaginary past which then casts a straight line to an inevitable future. This is consonant with this language of “Make America Great Again.” Without collapsing into sameness very distinct histories, can totalitarian regimes teach us something about the United States now?

Imaginary pasts are a necessary—though not sufficient—condition for totalitarianism. We can look at what so many countries have done with the imaginary past and say, “This is a landmark on this path.” It doesn’t mean that that’s where the road leads. The truth is, we don’t know where it leads. We don’t know what’s going to happen. In fact, we won’t know until after it’s happened.

I was at the Sydney Writers’ Festival this past week, and someone asked me a question from the audience about how the 1972 Munich Olympics should have been covered differently in light of what followed. It’s a beautifully anachronistic question. They didn’t know what would follow. It wasn’t predetermined. That’s the problem with history. It’s written in such a way that makes the course of events seem inevitable. To the extent that I can, I’ve always tried to write about accidents as accidents.

On one hand, you’ve spoken about outsiderness as a source of possibility for your writing. On the other hand, the production of an outside-as-threat is a condition of systemic oppression. Then there’s the question of the formation of an outside-from-within. You write, for example, about how the Kremlin’s articulated position of homophobia came about via a tactic of queer-baiting in response to protests in 2012.

That’s not the outside. That’s actually quite different in a very important way. That’s taking a group of citizens—pick a minority, any minority—and stripping them, legally or symbolically, of the protections of citizenship. That’s what Putin has done with queers. It’s been mostly symbolic, but it’s also legal because the Constitutional Court has interpreted the phrase “propaganda of homosexuality” to mean “the intentional and uncontrolled dissemination of information that can cause harm to the spiritual or physical development of children, including forming in them the erroneous impression of social equality of traditional and non-traditional marital relations.”

Erroneous impression of social equality is a key phrase. It enshrines second-class citizenship in law, something that had never happened in Russian law before and, to my knowledge, hasn’t happened since. In [Hannah] Arendt’s analysis, this ability to strip people of their “right to have rights” is a necessary condition for totalitarianism. Trump is doing the same thing.

You can read it in many different ways. You can read it as sadism. You can read it as the manufacturing of an internal enemy. And you can read it as stripping people of the right to have rights. The last to me is the most nefarious because it tells me that we’re doing real damage to the fabric of American society. It’s not unprecedented. Japanese internment is a perfect example. McCarthyism. Once you start going down that road, you’re hard-pressed to find a period in American history where it wasn’t practiced on some scale against some group.

Maybe I’m panicking because I haven’t actually witnessed it before, but it seems to me that the scale, the volume, and the lack of articulated opposition to this process are terrifying. Let me say what I mean by “articulated opposition.” As long as opposition is articulated as “But they’re good and deserving people,” it will be insufficient. The only opposition that could possibly work is one that shows how this treatment of immigrants destroys America: “We are good and deserving people such that we cannot do this to anyone.”

The social meaning of family operates on different scales. You’re speaking about the ways the Russian state criminalizes certain family structures. You’ve also invoked Hungarian sociologist Bálint Magyar’s concept of the “mafia state,” which refers to a state run by a patriarch who aims to accumulate power and wealth for his “family,” those who directly surround him. That applies to Putin’s Russia. And family-as-governing-body finds literal expression in the Trump administration. Is there anything to be said for how family functions across and between these scales?

It’s an interesting idea. I’m hesitant to start riffing on it. It requires a bunch of conceptual leaps to make a connection between the mafia state and the construction of the family.

I think the American idea of marriage and family is…sad. Existing within it, to some extent or another, always makes me feel contorted. I feel like I live in a country of people who are contorted, who have naturalized the contortion, and who are demanding contortion from their fellow citizens and their fellow family members to maintain this structure. I resist it to the extent that I can—but that’s also a form of contortion.

It strikes me that in your work, friendship is also important. I’m thinking in particular about the sustaining friendship between your grandmothers that you write about in Ester and Ruzya: How My Grandmothers Survived Hitler’s War and Stalin’s Peace. A less legislated or regulated form of relation, friendship can exist alongside and in the spaces of the failures of those more official relationships.

It is less regulated and less legislated. It’s also much less privileged. In mainstream American culture, friendship is optional. Family is mandatory. If you have friends and you don’t have family, then you’re certainly a second-class citizen socially. Also, legally. You can’t get tax advantages from shacking up with your friends.

In the 1980s, I was involved in drafting one of the first pieces of legislation on domestic partnerships as part of a working group in Boston led by [then] City Councilor David Scondras. I was arguing for a framework for creating domestic partnerships with more than two people. There was no way that was going to pass.

Think about this. This is when same-sex marriage seemed like an absolute pipe dream. In that context, it would make sense to position domestic partnership as something separate and different and apart. But, even in that working group, people wanted to specify that any benefit that was going to accrue had to accrue either to a blood relation or a sexual relation. If you didn’t share bodily fluids of some sort or another, then you weren’t going to have financial benefits or protection from the state.

Why did people object to an arrangement with more than two partners?

I think a lot of it was romantic, actually. People wanted domestic partnership to be like marriage. Some sort of marriage-lite. Now that I think about it, the problem was not that a framework with more than two partners wouldn’t have passed, but that none of the people I was talking to wanted that. They didn’t want to be thought of as friends or community. They wanted to be thought of as a married couple. Anything else felt like a dilution of their union.

Is that related to the appeal to the rhetoric of choicelessness when thinking about queerness and gender identity?

Of course. At the basis of that idea of marriage is the idea of one true love. You don’t choose it. You just have to locate that person who is predetermined, and then live together choicelessly ever after. Same with blood relations. You don’t choose them.

Even if you don’t have it yet, you can imagine that someday you will find that predetermined person, and then you will have your little island of stability. That’s actually a quote from my grandmother’s husband. He was a nuclear physicist. I did a story for Wired magazine on the nuclear research that continued in Russian towns long after 1990, when the state made massive funding cuts to science. In the town my grandmother’s husband worked in, they managed to synthesize one of the missing elements in the Periodic Table. He explained to me that they were looking for a particular combination of atoms that survives in a stable state for more than a fraction of a second, which apparently at that level in the Periodic Table is a long time. He said, “We’re looking for a little island of stability.” I remember thinking, “Oh my god. Aren’t we all?”

I think the idea that chosen communities should be somehow validated was too terrifying because chosen communities are unstable.

Often your work attends to moments of crisis or rupture where a different kind of future comes into reach. These are often contingent spaces—such as this working group you described—where the vision of another way is present, even if only for a moment, before it is foreclosed by what comes to pass. Are there any past visions of the future that you would want to return to, that you think might speak to this moment?

That is an invitation to be nostalgic, and I am so suspicious of nostalgia.

For all I’ve said, I’m really not at all nostalgic for the eighties or nineties. I may be a little bit nostalgic for the queer culture of the eighties, but that’s inseparable from being nostalgic for being twenty and being able to dance all night and for all sorts of abilities that I’ve lost just because I’m old. Because really, in many ways, for me, this country is a better place to live than it was in the eighties. This city is certainly a better place to live now than it was in the eighties. I don’t want to be disingenuous about that.

I’m not sure the question requires nostalgia. I meant it as a way of repositioning the imagination—bringing forward something that never was, but which once felt thinkable or imaginable before what was came to be. Are there any questions from the past no longer being asked in the same way that feel useful to this moment?

Absolutely. In the eighties, conversations about sex and relationships and structures of family and community were a lot more interesting. You know what? That’s one thing I’m really nostalgic for: queer community. Because I was gone [back to Russia] for so many years, I feel that I’m often just parallel to queer community. It lets me in, but I don’t live in it. If there was one thing that was amazing about the eighties, it was this sense of being in a community—a community of people I knew, and a community of people I didn’t know locally. And then a community of people I didn’t know nationally. Internationally, too.

It still happens. This past week in Sydney, I went to the invitation-only writers party at the opening of the festival. To set the scene: I got there, and there were a few people. There was very small food being taken around very slowly. This guy started talking to me. He was really snooty. At the end of the party, he came up to me and he said, “I’m sorry. I didn’t realize who you were.” He actually explicitly apologized for being snooty. It was that kind of party. And then, this young queer guy from Sydney introduced himself. The second question out of his mouth was, “Are you seeing anybody?” It suddenly hit me: I love how we do this just by virtue of being queer. Because we do. Because we can. For the next half hour, we were talking about how we negotiate monogamy and sex and his boyfriend and the person I’m seeing. All of that together. I get it in little bites, but I don’t get to have continuity with it.

Do you know models of community that have sustained that closeness and synthesis over years, or does that feel like it’s something that necessarily disintegrates or changes over time?

I think that people my age who stayed in this country actually do have that. When I reconnect with my older friends—people who were embedded in a queer community in the eighties—a lot of them have maintained that community. It’s a lovely thing.

I have community in Moscow. It was a much smaller community. It was our little node of four families, and then a larger community of maybe a dozen families. The little node traveled as a pack through life. When my friend was giving birth, her older kid stayed with me, and another friend did the rounds in Moscow, collecting newborn clothes and diapers. There was seamlessly shared childcare for the first few weeks. With us, the sort of thing that, in many societies, would be negotiated by the biological family was always shared. I miss that terribly.

I keep coming back to the question of holding difference within these spaces that are seeking a kind of social reconstitution—both within the communities they enact, as well as on a larger scale. For example, I’ve been at Black Lives Matter protests where a group of white people, ostensibly in solidarity, will start chanting, “Whose streets, our streets?”—no accounting for the fact that white entitlement to public space has so much to do with what produced the need for the movement in the first place. You often write about the social space of protest. Are there models you’ve seen for how we responsibly hold difference as we do the work of critiquing those structures that give disparate value to our differences?

ACT UP was trying to do that work. It was not just a protest space; it was a place of caregiving. Also of sex and a lot of sexual discovery. Women who identified as dykes started sleeping with men who identified as fags and it was weird and awesome and transgressive. It was a space of new connections and new relationships. I miss that. But we paid a hell of a price.

I also saw some semblance of that emerge in war zones. Things are thrown into relief when people are dying all around you. And from here it’s one step to say that life is precious, and when you realize you’re mortal, you no longer take anything for granted. But…yeah!

There is this great temptation to flatten difference because part of what appeals about these spaces is the sense of belonging. There was certainly a social hierarchy in ACT UP, and people who were dying were at the top of the pyramid. There’s a romance to being the tragic hero. Tragedy is compelling. Sympathy is addictive. In his memoir, Dale Peck writes about this guy, whom I knew quite well, actually. He had a very convoluted life story. He said he was HIV positive. All of it turned out to be a lie. I think that’s the greatest example of this hunger for belonging.

There was also this “lesbians get AIDS, too” thing, which I was always incredibly uncomfortable with. Of course lesbians get AIDS, but they don’t get AIDS as lesbians. AIDS didn’t accrue to lesbians as lesbians in the same way it accrued to gay men as gay men. But it seemed so unfair. Lesbians were taking care of all of these gay men. They were helping them fight. And some of them actually did have HIV. It was so tempting to use the frame because the frame was so compelling. That was an impossibly difficult thing to sort out.

Different stories obviously intersect differently with your own identities. How do you think about the ways those identities shape your reporting?

I don’t think of it in terms of identity. I prefer to think of it in terms of empathy. It’s a slight distinction. Empathy is based on experience. I think the older I get, the more qualified I am to exercise empathy. At this point, my experience has been so varied that it’s difficult for me to imagine a situation in which I can’t exercise empathy at all. Which is not to say that I’m some incredibly big-hearted person. I’m definitively not. But if you’re going to write about human beings, it’s better to have the capacity for empathy.

You describe The Future Is History as the story of “freedom not desired.” “Freedom” is one of these words that, in many contexts, has been evacuated of meaning—or rebranded as imperialism. What does freedom mean for you?

One of the moments when I felt most free was when I moved back to this country, and I realized I didn’t have to call my partner to fetch me late at night; it was safe just to go up to my own front door and open it. That goes a long way to making you feel like you can do things. When you’re constantly under attack, you’re not free. For me, freedom is really the absence of fear.