Once upon a time in America, five dollars would buy enough gas to drive from Tucson, Arizona, to California. This was during the postwar 1940s, when Jack Kerouac and Neal Cassady were making the cross-country road trips, at speeds over a hundred miles an hour, that would provide Kerouac with the material for his classic Beat novel, On the Road. Of course, if one doesn’t have the five dollars, it might as well be five thousand. And if one has the cash but feels guilty for having it, the exhilaration of unbounded flight becomes tainted by all sorts of qualms. Now surviving, now thriving, now crash-landing—at crippling physical cost to himself and destructive emotional cost to those close enough to him to recognize the dynamics of his riven psyche (family, friends, and lovers, among whom the writer Joyce Johnson was one)—Jack Kerouac forged a voice that has come to be appreciated as a landmark literary invention in American letters. Its elements are ecstasy arising from misery (like Thomas Wolfe), catalogues of desire (think Whitman and Melville), and Kerouac’s very own technique of reaching rock bottom before emerging with a recreated world in his hands:

I was delirious … hurrying to a plank where all the angels dove off and flew into the holy void of uncreated emptiness, the potent and inconceivable radiancies shining in bright Mind Essence, innumerable lotus-lands falling open in the magic mothswarm of heaven … I felt sweet, swinging bliss, like a big shot of heroin in the mainline vein; like a gulp of wine late in the afternoon and it makes you shudder; my feet tingled. I thought I was going to die the very next moment. But I didn’t die, and walked four miles and picked up ten long butts and took them back to Marylou’s hotel room and poured their tobacco in my old pipe and lit up. I was too young to know what had happened.

His is a voice like no other: musical in the variations-on-a-theme style of Bebop virtuosi (Kerouac’s actual jazz writings, alone, would put him in that pantheon); deeply evocative of spiritual perspectives, from mysticism to nihilism, without the academic lingo; invested with so many psychological flavors that melancholy tastes like joy, euphoria secretes soul-horror, and every Yes arrives twinned to its brother, No. It’s also a voice that has stimulated many imitators and a “First thought, best thought” school of non-revision, especially among poets. Unconscious impulse was the mantra at the time, and Allen Ginsberg, one of Kerouac’s closest friends when this voice was being developed, was the loudest publicist for Kerouac’s idea that spontaneity in writing is all. But make no mistake: The Beats revised. Those who were published, beginning with Kerouac, were edited. As any improvising musician will tell you, the continuous production of arresting and memorable art that seems spontaneous requires nerves of steel and the strictest discipline, although the rewards may be orgasmic and wild.

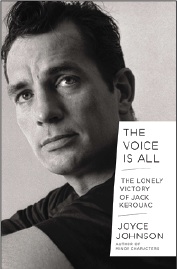

The cost of gasoline in the late 1940s is only a tiny detail in Joyce Johnson’s magnificent bildungsroman biography, The Voice Is All: The Lonely Victory of Jack Kerouac. It takes her subject from childhood as the son of French-Canadians in Massachusetts past the point when the young man throws away his football scholarship to Columbia and spends several years as a wanderer on land and sea before he enters one of the bleakest moments in his life, in his thirtieth year. The book is a cliffhanger of sorts, with its last glimpse of the writer as a kind of Pandora, clinging to the hope that, although he is sinking deeper and deeper into physical and psychological despair, his work will endure. At that moment, indeed, only fortitude and faith could have kept him going: Kerouac was poverty-stricken; heartbroken that he had deep-sixed two marriages and failed to win commercial and critical success for his first published novel, The Town and the City; filled with reservations that he hadn’t lived up to his artistic standards in his next novel, On the Road; suffering from phlebitis (acquired through addiction to Benzedrine) and other longtime chemical insults to his once-Davidic, athlete’s body; and prey to one of the suffocating depressions that had overtaken him since the funeral of his elder brother, when he was only four. “I feel like I’ve done wrong, to myself the most wrong,” Kerouac wrote to Cassady. “I’m throwing away something that I can’t even find in the incredible clutter of my being.” It was November 1951, and he was dashing this off in his mother’s basement apartment in Queens.

Here, Johnson includes an addendum—one of the most brilliant authorial strokes in the book—that pulls back to a long shot, and we see Kerouac’s imagination galvanized by what he has been writing to Cassady. This letter, the first of four, confesses a flattening despair, and becomes the launching pad for Kerouac’s greatest invention—his mature literary style. With this scene, Johnson has completed her reconstruction of the Kerouac her younger self would meet; she has solved the puzzle of who he was and why he was so restless and tormented; and she achieves her book’s mission: to pinpoint Kerouac’s discovery of the literary voice he would use for the rest of his abbreviated life.

In the nearly two decades left to him, he would write many other novels, enjoy some happy as well as harrowing hours, and, for a little while, light up the life of a young woman who, more than a half century later, would return the favor by illuminating his life and work for a new generation. If I say that The Voice Is All deserves to be read alongside The Sorrows of Young Werther and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, both autobiographical novels about writers coming of age, I do not mean that Johnson has written fiction—though, as the author of several well-received novels herself, she might easily have done so. On the contrary: Her biography is scrupulous, heavily footnoted; and spot comparisons with Paul Maher’s acclaimed chronicle Kerouac: The Definitive Biography strongly suggest that she didn’t stray from the well-documented facts. Indeed, she has been fastidious in offering every point of view whenever the records disagree. Johnson has poured herself into this book in the way artists do into works of the imagination.

As Kerouac’s lover for two years in the late 1950s, Johnson was part of his larger story—an experience she has already memorialized in her award-winning 1983 memoir, Minor Characters, and enlarged upon in her annotated collection of her correspondence with Kerouac between 1957–58, Door Wide Open. Half a shelf in the Kerouac library is taken up with memoirs by his lovers, carnal and platonic. But Johnson has more than personal anecdote to offer. In her late seventies now, she is a woman of some experience: She has been married twice, both times to painters, and has a son, the writer Daniel Pinchbeck. She has worked in book publishing, taught writing at major universities, and has proven herself as an eclectic author. In fact, at twenty-one, Joyce Glassman (her maiden name) was awarded an enviable contract for her first novel, at an age when Kerouac couldn’t get his manuscripts in a publisher’s door.

It was around then, at the dawn of her adulthood, that she and Kerouac met on a blind date set up by Ginsberg. Their love affair wouldn’t last. Well before she met this charismatic man with the smashed life, she had fallen in love with writing itself as represented by Henry James, whom Kerouac disdained for his practice of intensive revision. Although their affair came to an end over Kerouac’s insulting displays of infidelity and because Johnson’s Jewish heritage was unacceptable to his mother, there were deeper reasons, too. The very deepest may have been that Johnson espoused a writing process in direct opposition to the one he practiced. If they had stayed together, he would have had to reconsider not only the drug- and alcohol-induced highs and lows that stimulated his writing but his very identity as a writer. Kerouac did record their romance, though, in his autobiographical novel about the late 1950s, Desolation Angels, which he wrote after their painful break-up on a Manhattan street corner, just as George Balanchine was restaging “The Seven Deadly Sins,” Nabokov’s Lolita was unhinging readers, and the US began to perceive there was something amiss in Cuba and Vietnam. He writes of Johnson (whom he calls Alyce Newman in the novel): “[I]t was the beginning of perhaps the best love affair I ever had … Alyce and I were wonderful healthy lovers—She only wanted me to make her happy and she did everything in her power to make me happy too, which was enough… .” In the novel, the narrator asks Alyce who her literary models are, then adds that “all her models were wrong, yet I knew she could do it, be the first great woman writer of the world, but I guess, I think, she wanted babies anyhow anyway—She was sweet and I still love her tonight.”

The Voice Is All patiently chronicles many trailblazing and sometimes downright unbelievable aspects of sexual relations among the Beats (thousands of “sticky” encounters and not one reported incidence of an STD?), while digging for the impulses that drove so many of them to misogyny and callousness toward their children. It offers proof that Kerouac had vision when he saw greatness in Joyce Johnson, and suggests that Henry James was a more sustaining model than those whom Kerouac claimed (Wolfe, Hemingway, Céline, Genet, Antonin Artaud). The book also evokes the truism that putting one’s writing over and above the human beings in one’s life may bring fame and love, but only after one is dead. Yet Kerouac, wracked from earliest childhood by the split between his background as a speaker of French-Canadian Joual and his lifelong effort to forge something new in English, wanted desperately to be recognized and loved. He also wanted to make a living from his work. To complicate matters, he was on a search—almost mythic in its obsession—for a father and a mother of dreams, as well as for the Penelope-wife who would ground him with her strength and beauty. He thought his male friends and editors and critics would help him realize his attempts to become a whole, fully functional person. Some were able to do that now and then. Many tried, in various idiosyncratic ways. All ultimately failed.

Although I read the Beat poets as an undergraduate at Vassar in the late 1960s—and heard many give readings—I never could bring myself to read Kerouac’s works. That was the writing my Yale fiancé and his circle favored. They were boys’ books, even by the look of them. I knew intuitively that the women within wouldn’t be happy campers. But that was then. When I recently went to a bookstore near Barnard, where I teach, to purchase a copy of On the Road for this review, the young woman who rang it up couldn’t resist saying how much she loves the book. I wonder if she will read The Voice Is All; I can’t help but wonder what she will think of it. For here as elsewhere in her books, Johnson addresses, without compromise and sometimes with asperity, the Beat misogyny she was able to observe firsthand. Even so, she avers that, although most of the guys were jerks to women, their deeply held conviction that Cold-War-addled, atom-bomb-anxious America needed a sexual revolution led ultimately to the rise of feminism, which benefited women, too. As for the concomitant Beat epiphany that the repressed, flannel-suited suburbs needed to be returned to Eden via a massive ingestion of recreational drugs, Johnson looks on with dismay. But she doesn’t get on a soapbox—she just reports.

It’s worth noting that she was also there to hear Kerouac’s outbursts of anti-Semitism, even though she, Ginsberg, and some of his other intimates were Jewish; and she goes on to explain that the rhetoric was likely engendered by a pair of very messed-up parents and early childhood experiences. To her credit, in the course of nearly 440 pages, she’s careful to permit only a few references to Kerouac’s insanely demanding mother as a monster. She also accords Kerouac the respect of demonstrating, through quotation and paraphrase of his own work, that whatever criticism anyone may have had of him, he thought of all of them first. Johnson wants us to understand that, just as no Kerouac chronicler is likely to surpass Kerouac in scenes that detail his lovemaking, no critic’s verbal lash could surpass his own self-loathing. Her scene of the twenty-something Jack passing out in a public toilet during one of his countless benders, as sailors evacuated themselves on his slumped body, is a vision of Hell that, I daresay, rivals Rimbaud.

But more rewarding than Johnson’s inside storytelling are her insights into Kerouac’s ambitions as a writer. She charts the evolution of his outsider identity and his assimilationist ideal; his ideas concerning what is a first draft and what is final; his double allegiance to simplicity and complexity; his wish to have his sentences parsed like poetry even as they struggled to project complicated stories and philosophical speculations; his shyness when he was sober and his appetite for adventure when he was drunk.

This past decade has seen a resurgence of interest in Kerouac. Owing to the gift of his papers to the Berg Collection of the New York Public Library, many ideas about him have had to be revised; and books such as Johnson’s, as well as Maher’s, and a collection of Kerouac letters have been made possible. The Library of America has just published a collection of his poetry, edited by Marilène Phipps-Kettlewell. More scholarship is probably pending. And yet, only publications that have been authorized by the estate of the writer’s third and last wife, Stella Kerouac, are permitted to quote directly from his unpublished papers. One of the beauties of The Voice Is All, which is not so authorized, is how deftly and carefully Johnson presents Kerouac’s unpublished thoughts and writings in paraphrase. She is a marvel, also, at delineating borders when it comes to distinguishing his thoughts from other observers’ and memoirists’, including her own. To see how and why she learned to do that, one might go back to Minor Characters for her initial account of how important Kerouac’s first novel, The Town and the City, was to the twenty-one-year-old Joyce Glassman. She had stolen a copy of it from the shelf of the literary agency where she was working and, as she read, she was overwhelmed by the sense that its author, a total stranger, was writing her own life as if he had X-rayed it. Yes, Kerouac had uncanny vision, as in this from On the Road:

The mere thought of looking out the window at Mexico—which was now something else in my mind—was like recoiling from some gloriously riddled glittering treasure-box that you’re afraid to look at because of your eyes, they bend inward, the riches and the treasures are too much to take all at once. I gulped. I saw streams of gold pouring through the sky and right across the tattered roof of the poor old car, right across my eyeballs and indeed right inside them; it was everywhere.

Thanks to Johnson, it is possible to understand just how complex the origins of his prose were. You may still not share her pleasure in Kerouac’s writing, but you aren’t likely, as I once did, to discount it.