On November 14, 2012, Schuyler Towne joined Joshua Foer onstage at the Institute Library in New Haven, Connecticut, as part of the ongoing series “Amateur Hour,” in which various tinkerers, zealots, and collectors discuss their obsessions. Towne, thirty, is an expert lockpicker. Since 2006, he has competed in several locksport competitions, including the Dutch Open at LockCon, in Friesland. Towne’s other passions have included competitive curling as well as theater (which led to a brief off-Broadway career). The conversation that follows was recorded live and has been edited for brevity and meaning.

Joshua Foer: So we sent out an invitation to everybody who was coming here tonight to bring the most challenging-looking lock they own, and I see one that is very intimidating right here. Tell us a little about this lock.

This is basically the U-Haul version of a lock made by the Abus company called the Abus Diskus. It’s got a really tight keyway. Everything is at a smaller diameter, which means it can be annoying to work on with normal tools. The Abus Diskus and the Brinks R70 and the Master 40 are all basically the same lock, and they tend to be kind of a rite of passage in the American locksport community because usually, in order to pick them, you have to apply too much tension. Tension is very important when you’re picking locks. You usually want light tension. People say that you want three butterflies’ worth of tension on the end of the pick, if that’s a useful measurement. And with this lock, in order to overcome the force of the shackle, you have to apply very heavy tension, which makes it difficult to feel what’s going on inside.

I suspect that talking about lockpicking is a bit like dancing architecture. But walk us through what you’re thinking as you try to open this lock—and what’s that small case in your lap?

This case was given to me by one of my students because he got sick of me using all sorts of crappy cases. I use cardboard for my trays, and I use nickel tweezers for pinning locks. I’m really cheap about all this stuff. So he went out and got me a gorgeous pair of $40 tweezers and this beautiful box for picks and my practice locks, things like that.

All of these things look more or less like shards of metal.

Like dental tools. The best lockpicker in the world is a German dentist. Anyway, some of these are of my own design, like these here, which are chemically etched and were spot-welded in my bathroom. This here was one of the first picks I ever owned. These over here were made by a guy who goes by the handle Criminal Hate, a really good pickmaker. I have a couple here made by a guy who goes by Tooly McGee. I love his work. This is a hand-molded pick made by a guy named Legion. All sorts of stuff. I made this small tool from a piece of metal removed from a windshield-wiper blade.

You made that?

Yes. I go to AutoZone after work when I close, at my job as a barista, and I pick through their trash and take as many windshield-wiper blades as I can. It’s a very good time of year for it right now.

Okay, so what’s inside this lock that you’re about to open, and how are you going to open it?

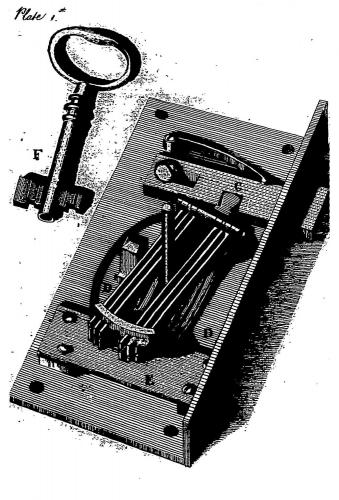

If you look at a key, you’ll see that it has several peaks and valleys on it. You can tell the number of pins in your lock by looking at the number of valleys. The number of valleys is the number of pins. The depths of those valleys correspond directly to the length of the pins. Now, in this case there are four pin chambers, and each of those pin chambers has two pins in it—a key pin and a driver pin. It’s the driver pin that does the locking in a lock. The key pins are what I manipulate with the pick. The driver pins sit between what’s called the plug—this portion that will rotate when you put your key into it—and the upper part of the lock—what’s called the bible. So part of the driver pin will be in the plug and part of it will be in the bible. Above that is the spring, pushing everything into the keyway.

So basically, to open this lock, the name of the game is to get all these little pins to be precisely aligned along an even plane so that the barrel turns.

Exactly.

How are you doing that with that little tool in your hand?

Well, by applying a light pressure on the plug, I’m taking advantage of a lot of tiny mechanical differences in different parts of the lock. Not every pin will be exactly the same. Some might be slightly ovoid, some might not be perfectly deburred, they might even be misaligned from when they were milled—equipment, you know, slowly degrades when you’re milling the locks, and over time these imperfections will be introduced into the lock. But by applying light pressure, we’re finding the weirdest pin first. When we find that pin, and lift it up, the plug will actually rotate a tiny amount, just the minutest amount. But when it does, it traps the driver pin outside of the plug, and it’s no longer blocking the plug. And now the next-weirdest pin is binding it, and so I search for that one. And when I set that pin, it rotates a tiny bit, and so on and so forth, until all the pins have been set to the positions that the key would naturally set them in, at which point it rotates.

One of the things I’ve heard you say is that you can break into my house.

I could probably break into the majority of people’s houses in this room, yes.

And presumably, you’re not alone—there are a lot of people like you who can break into our houses, which raises the question: Why do we even have locks?

Well, that’s directly related to the Great Lock Controversy of 1851.

I was hoping you were going to go there.

The reason we bother even having locks on our houses is because, a long time ago, we near-collectively, as a society, both here and in Europe, made an unconscious decision that we were going to treat locks as a social construct more than a mechanical one. The lock on your front door has likely not had a major revision since 1886, when the patent for producing keys with a shape to them was brought about. Before that, it was flat steel keys, for the most part.

What you’re saying is that we all collectively acknowledged that the technology we’re using to keep our doors closed is basically really old, not very useful, and yet we keep putting locks on our doors anyway?

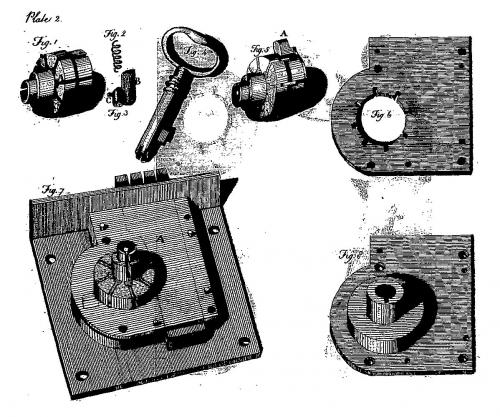

Yeah, and there isn’t a good reason for that, because there are phenomenal locks out there. Anyway, from about 2,000 bc-ish to 1770-ish, lock technology was awful. But in the late 1700s, a man named Robert Barron was credited with the invention of the first lever lock in modern history—a lock with a moveable tumbler, so that a key would affect something moving inside. Around this time, a man named Joseph Bramah writes Barron a letter saying, Hey, awesome lock, but here are all the problems with it, and here are all the things that you can do improve it, et cetera. But Bramah doesn’t improve upon the lock. Instead, he has a much crazier lock in his back pocket, the Bramah safety lock, really one of the first locks that somebody could put in your hands and say, “Though I made this, I cannot open it. Though I’ve sold one to you, and you can pick it apart and look at it, you won’t be able to open somebody else’s, even though it’s made with the same technology, just with different keys.” Though you can spec this system, you cannot defeat this system. And that was an absolute sea change for the industry.

And that was the lock at the center of the 1851 Great Lock Controversy?

Exactly. Because soon after he makes this lock, it gets picked by somebody. And people start saying, “Oh, you can pick this thing with a hairpin!” And people start taking out advertisements saying it’s worthless, that it’s just as junky as everybody else’s. A locksmith began advertising his services for opening them for folks who’d lost their keys.

So we’ve got this impenetrable lock that is actually penetrable.

Yes. Somebody manages to pick it, and then Bramah creates an improvement on the lock: serrations.

Got it. Now, remind us what you’re doing with the lock in your hands—

I’m actually going into the open end of the keyway now. Still going clockwise, though, and not getting much feedback. So at some point I might—oh! Bam. Open. There you go.

[Applause.]

Okay. You’ve got me on pins and needles waiting to find out how this impenetrable lock that was penetrable resulted in us changing how we think about security.

Can I pick another lock while we’re talking?

Sure.

[A Master combination lock is handed to him.]

So we’re going to open this one with a beer can and a pair of scissors, but I’ll keep talking about the lock controversy while I do it. [He proceeds to slice off both ends of a beer can, then cut the can lenghthwise and into strips.] The thing about Master combination locks, by the way, is that for a very long time they coded algorithmically rather than randomly. So if you can derive any single number in the combination, you can pop it into a spreadsheet and get, like, forty-four combinations to try, one of which will work. There are also extensive codebooks. I have a ton of books just laying around my house that are filled with combinations for these.

Anyway, the Great Lock Controversy. So, in order to assure everyone that his lock is awesome again, Bramah puts up a challenge in the window of his shop, and he actually puts the Bramah safety lock on a wooden board with an engraving that says something like, “The operator who can make a tool to open this lock will be awarded a prize of 200 guinea upon its opening.”

Which I presume is a lot of money.

I would assume so. In the meantime, all sorts of other locks are being invented, and this concept of the lockpicking contest really takes off——both in England and America. And this lock sits in Bramah’s window in Piccadilly Square from the late 1770s, early 1780s, to 1851 before it’s successfully opened.

For seventy years?

Yeah, like four generations of people. People lived and died genuinely believing that the security arms race was over, that Bramah had solved it. And as important as his lock was to the future of security, the fact that he opened up this contest was also important, because it led to similar things happening all over the place. The Royal Society actually put a bounty on great lock designs, with the idea being that you could bring them one and they would reimburse you some amount of money for your efforts as long as you allowed someone to make use of your design. You couldn’t patent it, that was the only rule. It was sort of a precursor to the open-source movement, with this society of engineers and artists and great thinkers actually paying for great lock designs.

Show us what you’ve been doing here.

I’ve cut a little shim out of the aluminum, with a little handle. I’m going to tuck it in along the outside of the shackle that’s on the opposite side of what’s called the locking dog. I’m going to try and get it seated in there nice and deep, then I’m going to pass the handles around the shackle, and now, as I rotate 180 degrees, and turn my handles to the outside, the shim will interrupt the locking dog. Agh, I tore it apart.

Did you break the lock?

I broke my shim. I’ll make another one. Okay, so everyone else starts doing these competitions, and an American named Alfred Hobbs makes a name for himself by winning them. At the same time he invents his own lock. His thing was, he’d visit bank directors and tell them, “If I can open your lock, you have to buy my lock and install it.” And bankers would say, “Pfft, go for it.” And he would open their locks and consequently sell a lot of his own. One of the best stories about Hobbs takes place at the Merchants’ Exchange in New York City, sometime in the 1840s. They were holding a public contest—thirty days to test against their vault, $500 on the line. Hobbs picked it in an hour.

And by the way, this idea of giving someone thirty days to work on a lock was a direct result of this concept of perfect security. Today, I only know of one nation—Japan—that tests for surreptitious entry on a national level. They will actually give a rating for your lock.

They’re testing to see how pickable a lock is, and then the lock gets scored?

Right. A team of pickers is given fifteen minutes to work on a lock. If they don’t open it in fifteen minutes, they give three master pickers an additional fifteen minutes. If the lock isn’t open after those two sessions, it’s considered “high security.” And I know master pickers. I have people approach me and say, “Oh man, I’m down to five minutes on the Schlage Primuses, but my stupid Medeco times are up to ten minutes.” Those are two very serious American, high-security locks. I’ve picked a small handful of Medecos, but I’ve never come close to opening a Schlage Primus in my life. These people are popping them in, like, five minutes—they’re incredibly talented. They are master pickers, I am not. I’m a talker, I talk a lot.

And the funny thing is, only a few of these people are actually locksmiths. The best picker in the world is the German dentist I mentioned. Manfred Bölker. He’s amazing.

Let’s talk about him for a moment, because you’ve gone head-to-head with him. I think most people will find it amazing that there are competitions where people get together from all over the world and are handed a lock and told, “Go.” What is an international lock-picking contest like?

The first one that I went to was in 2006. I was terrified. Before going to the competition, I had yet to pick a six-pin lock. Just the idea of picking a six-pin lock was incredible. Of course, in the competition, it was only six-pin locks. So I was terribly intimidated before I went out. I flew into Amsterdam and stayed with somebody there—slept on the floor of their office—and then I was given a ride up to Friesland.

What are the competitors like?

It’s just a bunch of randos, which was the best part. I figured there would be a type, that I would encounter a group of very serious and incredibly hard-core, competitive people. And they are hard-core, competitive people. Well, let me just tell you about the number-two lockpicker in the world, Arthur Bühl. He’s this six-seven German private investigator. He has this amazing mullet that goes all the way down to his thighs.

Of course he does.

And he wears these incredible, seventies-looking suits, and he chain smokes, and he drinks constantly. My first time there, I never saw him go to sleep. At four in the morning, I’d be wandering off to bed and he’d be holding court somewhere, picking locks. As best I can tell, he went three days without ever having slept. He’s just this incredible force of nature. Watching him pick is like witnessing a tiny act of violence. He’s just massive.

On the exact opposite end of the scale is the number-one picker, this German dentist who will hang just like everyone else, he’ll stay up late, he’ll drink, and he’ll talk. But he’s so mild-mannered, and much quieter, and much more studious. And his picking style is directly related to that personality. He is just so incredibly patient and methodical and observant.

How many of these people are criminals?

At the competition? Not a one of them. It’s a small, like 80- to 100-person, invite-only event, and you have to be vouched for by somebody in order to attend.

Is it possible that they’re just criminals who are so good they don’t get caught?

No. There’s an extraordinary ethical line. It’s hard to explain. I can give you all kinds of anecdotal evidence of people I know in the locksport community who have been approached to do things like give expert testimony, or train cops. I mean, a good friend of mine has a day job, spends a lot of his time working, but when he comes home at night, he is actively advancing the art of lock forensics. And this is in his spare time. This is the mindset of almost everybody in this community.

Are there any locks that cannot be picked?

Sure. One of them is the Abloy Protec. It’s a disc-detainer mechanism. Disc detainers are different from pin tumblers, but we can still apply the same method. When you apply force on a system and then manipulate the individual tumblers, as that force is being applied, you can set those in place or you can decode what’s going on. The whole concept of tension and manipulation of the tumblers is called the tentative method, and it appears to have come about around the time of the invention of the Bramah safety lock.

So, imagine if you could create a lock that, the moment you applied that tension, you could no longer manipulate any of the tumblers inside. Your only real shot is arranging them in a certain pattern and then applying tension and hoping for the right combination—slowly brute-forcing your way through it. That’s what the Abloy Protec managed to do. The moment you applied tension, you can no longer manipulate it. So we have to learn a new way of picking.

The idea behind this series, “Amateur Hour,” is to reclaim the word amateur from its pejorative connotations—as somebody who is unschooled—and reclaim its original etymology, from the Latin word for love—people who really love the things they choose to pursue. So what is it about lockpicking that moves you?

You know, the first lock that I picked had this yellow band around it, with stacked sheets of metal, like you would see in a normal Master lock. This was just in 2006, I was twenty-two. And the great thing about the very first lock that I picked is that when the plug rotated, the shackle was sprung, and it went, “Shnk.” It was this great, visceral, auditory, physical—I mean, it shook in my hand. And then I picked another lock, and another, and then I started teaching people around me how to pick locks. As much good information as I’ve given over the years, I’ve given so much misinformation, because I operate with enthusiasm far more than I operate with accuracy.

I think that’s a sound principle to live by.

But that excitement. I mean, I picked everywhere for a while. At our local bar, I would pick regularly. If I had a couple too many drinks, I would try to make the people at the tables learn how to pick. I carried around this messenger bag with a bunch of padlocks on it that I’d never opened, like a bandolier, and I would pick as I was walking to work. I was picking constantly in those early days. I met this locksmith in a sketchy, sub-basement parking lot, who, for like a couple hundred dollars, gave me several hundred locks, just transferring them into my trunk of my car. It was awesome. I would just pull locks apart, I would take photos of the locks. And then, after about a year and a half of that, I didn’t really care anymore. It had been a great ride. That tends to be how I am with things.

So, some colleagues noticed that I’d stopped picking at work so much, that I was clearly losing interest. I accidentally left my Facebook page up one day, and somebody posted something like, “Looks like lockpicking is over. Now I’m just into My Little Pony”— some goofy, off-the-cuff thing. Before I even saw the post, I had people calling my cell phone, e-mailing me, people were posting on it like crazy. The community just reached out its internet claw and hauled me back in.

And one of the big projects I did when I decided to recommit myself was catalogue my entire collection, which at that time comprised about 700 locks. Today it’s up in the thousands. And in the process of doing that cataloguing I found a padlock that said Yale & Towne Manufacturing Company. Henry Robinson Towne and Linus Yale Jr. They only worked together for three months. But looking into it, I realized that my branch of the family was his branch of the family, which had branched off generations before. So there isn’t a really good blood connection to him at all, but still, he’s one of ours.

And what Henry Robinson Towne did was to take this incredible collection of beautiful mechanical engineering ideas and make them the standard for the world to use. He wrote about locks extensively, and he thought about them extensively. He was this great thinker on the subject of what security meant. He was probably the last great American manufacturer that beat this drum of “any lock with a key can be picked.”

And it was Yale who’d had that epiphany, who’d shared it with Towne, because—well, here’s the three-sentence version of the Great Lock Controversy: Hobbs rolls in, picks all the locks. The British, all of their hearts are broken, and it changes society after about a decade. Because during that decade, many more contests are held, all of the locks are opened, confidence and public faith completely falls away. And it’s that lack of faith that created the social contract, because after Hobbs, people thought, We’re going to get back to a perfect lock! Somebody’s going to invent it! And there were amazing locks coming out and getting defeated, faster and faster and faster as these methods became codified and tools were developed. And after so much of this, public trust just completely fell out. Punch magazine put out an editorial that boiled down to: We understand that you need to test the security of locks by picking them. We also understand that you need to learn anatomy by cutting people apart. Let’s not do either in the streets. And people became much less tolerant of these open bounties and less tolerant of these picking competitions. And basically, by the latter half of the 1880s, people said, “Screw it, this is good enough. If there’s a lock on the door and we’ve all decided to live in a society together, well, that’s cool.” And so your lock today is incredibly similar.

Special thanks to Lightside Photographic Services, New York.