Last year, László Krasznahorkai, the apocalypse-obsessed Hungarian novelist, won the Man Booker International Prize, which recognizes “continued creativity, development and overall contribution to fiction on the world stage.” Past winners are heavyweights—Alice Munro, Philip Roth, Chinua Achebe—and the honor usually only reaffirms what we already know. Out of all the big prize-receivers, Krasznahorkai is perhaps the most innovative and exasperating. Until recently, he hasn’t had much of an audience outside of Europe. But thanks to New Directions, purveyors of chic experimentalists like Clarice Lispector and César Aira, and two brilliant translators, Ottilie Mulzet and George Szirtes, we’ve been graced with Krasznahorkai’s four taxing, darkly comic novels: Satantango, War & War, The Melancholy of Resistance, and Seiobo There Below. Read together, his novels delight, confuse, surprise, and fatigue the careful reader, often within a single page. In other words, don’t try to catch snatches before bed. Krasznahorkai relentlessly compounds clauses and asides and, at times, stretches the sentences to seven, eight pages. In Melancholy of Resistance, there are no paragraph breaks. And yet, on visits to the States, his readings attract standing-room-only crowds. In the last few years, his work has garnered a cult following. On two occasions, during the preparation of this piece, people stopped me in cafés, pointing to the stack of Krasznahorkai’s books on my table, expressing their enthusiasm for his bleak comedy and particular brand of absurdity. Both times, I was urged to seek out the dreary, black-and-white films on which he’s collaborated with the avant-garde director Béla Tarr. The conversations ended in starry-eyed camaraderie, akin to the sparks between thrill seekers who’ve both traversed Machu Picchu. This zeal seems to rival that of the early days of Roberto Bolaño’s posthumous fandom. The growing attraction to work so strange and demanding begs the question: What launches an innovative writer onto the global stage? That question is as easy to answer as, “What the hell are we going to do about climate change?”

Last year, László Krasznahorkai, the apocalypse-obsessed Hungarian novelist, won the Man Booker International Prize, which recognizes “continued creativity, development and overall contribution to fiction on the world stage.” Past winners are heavyweights—Alice Munro, Philip Roth, Chinua Achebe—and the honor usually only reaffirms what we already know. Out of all the big prize-receivers, Krasznahorkai is perhaps the most innovative and exasperating. Until recently, he hasn’t had much of an audience outside of Europe. But thanks to New Directions, purveyors of chic experimentalists like Clarice Lispector and César Aira, and two brilliant translators, Ottilie Mulzet and George Szirtes, we’ve been graced with Krasznahorkai’s four taxing, darkly comic novels: Satantango, War & War, The Melancholy of Resistance, and Seiobo There Below. Read together, his novels delight, confuse, surprise, and fatigue the careful reader, often within a single page. In other words, don’t try to catch snatches before bed. Krasznahorkai relentlessly compounds clauses and asides and, at times, stretches the sentences to seven, eight pages. In Melancholy of Resistance, there are no paragraph breaks. And yet, on visits to the States, his readings attract standing-room-only crowds. In the last few years, his work has garnered a cult following. On two occasions, during the preparation of this piece, people stopped me in cafés, pointing to the stack of Krasznahorkai’s books on my table, expressing their enthusiasm for his bleak comedy and particular brand of absurdity. Both times, I was urged to seek out the dreary, black-and-white films on which he’s collaborated with the avant-garde director Béla Tarr. The conversations ended in starry-eyed camaraderie, akin to the sparks between thrill seekers who’ve both traversed Machu Picchu. This zeal seems to rival that of the early days of Roberto Bolaño’s posthumous fandom. The growing attraction to work so strange and demanding begs the question: What launches an innovative writer onto the global stage? That question is as easy to answer as, “What the hell are we going to do about climate change?”

W. G. Sebald, who shared Krasznahorkai’s meandering, melancholic spirit—and the same penchant for winding sentences—said, “The universality of Krasznahorkai’s writing rivals that of Gogol’s Dead Souls and far surpasses all the lesser concerns of contemporary writing.” What exactly are those “lesser concerns”? For Sebald, it was the unexamined self. As Joshua Cohen writes in the New York Times, “Sebald’s self-definition was the shadow subject of everything he wrote.” He often sought to reconcile himself to the horrors of the Holocaust, to World War II, and to the memories of his father, a Nazi soldier who was imprisoned in a French POW camp for the first three years of Sebald’s life. Krasznahorkai’s novels consider hamlets in decrepitude, deranged circuses, imprisoned minds, and varying degrees of personal and political hell. Dead Souls follows a schemer who roams the Russian countryside, buying up dead serfs—censuses only appeared every ten years—in order to muster collateral for a loan so that he might purchase land. The book is often seen as a satire of Russia’s social systems after the War of 1812. Lesser concerns, it seems, are those that eschew the self in relation to bloodshed, psychological trauma, the upheavals of war.

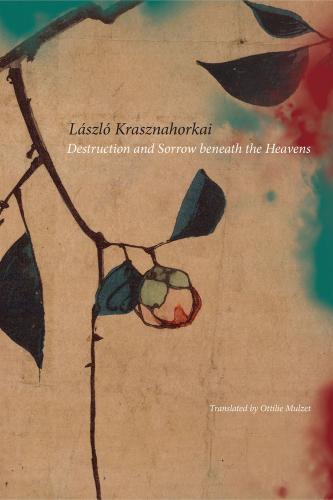

But universal doesn’t necessarily mean translatable. If it did, we might have seen Satantango, Krasznahorkai’s first novel, appear in English sooner than twenty-seven years after it was originally published. But in his latest book, Destruction and Sorrow beneath the Heavens: Reportage—his first book of literary reportage—Krasznahorkai shows an intense, empathic engagement with a foreign culture, an outlook that US writers ought to admire.

Unless American readers do some digging, it might be hard to come up with a list of great Hungarian writers—or any Hungarian writers, for that matter. English translations are sparse. Aside from the publication of Péter Nádas’s gargantuan, intricately structured Parallel Stories (FSG 2011), as well as gems like Gyula Krúdy’s Adventures of Sindbad (2011) and Magda Szabó’s Door (2015)—the latter pair published under the imprint of the New York Review of Books—English speakers have been largely deprived of the modern Hungarian canon. The language is complex (a hodgepodge of borrowed words and phrases range from Turkish to English) and the country is small (roughly the size of West Virginia). Its literature has long been overshadowed by that of its Russian and German neighbors. Postwar Stalinization confined literary expression to socialist realism. In the 1950s and sixties, many writers, including Gyula Obersovszky and Tibor Déry, were imprisoned.

Hungarian is one of a handful of languages in the Uralic family—the same family as Finnish and Estonian. Because it frequently employs voiceless stops, fricatives, and nasals, Hungarian is often grouped with Arabic and Japanese as one of the most difficult languages to learn. In his introduction to Krúdy’s Sunflower, John Lukacs points to “the loneliness of the Hungarian language” as one of the culprits for Krúdy’s obscurity. Péter Esterházy, Krasznahorkai’s contemporary and one of Hungary’s major modern voices, views this isolation as empowerment. He quotes Mihály Babits, saying the language “lacks solid, ready-made phrases.” As a result, Esterházy adds, “there are no clearly defined prohibitions; in a certain sense everything is possible and everything has to be invented over and over again. Every single sentence is an individual achievement.”

This notion explains two things: One, writers such as Esterházy, Nádas, and Krasznahorkai, who are often said to revel in stylistic experimentation, don’t necessarily experiment at all. They embrace their language, albeit with books that are long, dense, and strange. And second, in Krasznahorkai, every sentence conjures a moment or thought or action to the point of seemingly unending exhaustion. He collects sensations with long arms, exploding single gestures and freezing them against frenzied backgrounds. His realism is madness. Strains of thought loop and lunge and, as in the Austrian maximalist Thomas Bernhard’s work, don’t let up. Sentences sometimes last several pages, leaving you to double back, dizzy in search of the kernel of subject and verb that began the whole thought or action in the first place. But even in this dizziness—and unlike the work of some of the more “difficult” maximalists like Thomas Pynchon—Krasznahorkai’s sentences continually qualify minute gestures. For pages, time will sometimes stop altogether, and you are suspended in grammatical unreality while every speck of dust is taken into account. An intense logic cuts through the depths of despair. Krasznahorkai’s awareness is encyclopedic, but he neither deploys empty lyricism nor overextends intellectual prowess. There is, as well, a peculiar melancholy, a humor so subtle and strange that one would have to go to Kafka to match the uneasiness of laughter in the face of seemingly unbearable pain.

Hungarians’ language has left them exiled. History, too, has left its bruises on their psyche. Communism flanks their memories; the Holocaust haunts the remaining Jews, who made up roughly 6 percent of the population during World War II, and now make up less than 1 percent. Throughout the Cold War, Hungary’s writers were relentlessly censored. So they translated. It was also a period of intense purification. In 1944, half a million books were burned in Budapest. Post–World War II, a political committee sifted through the translations of Shakespeare, selecting one to canonize in the name of uniformity.

Like the Czechs and Russians, Hungarian writers are often unafraid of existential directness. Krasznahorkai’s War & War begins, “I no longer care if I die, said Korin, then, after a long silence, pointed to the nearby flooded quarry: Are those swans?” His books are full of these kinds of ruminations and occasionally absurd non sequiturs, which seem to bear the mark of modern Hungarian literature writ large—lyricism verging on a kind of transcendental meditation and keen observations of the natural world. But Krasznahorkai does curious things: He takes this fondness for the Romantic a step further, maybe three steps further. In Sunflower, Krúdy describes a flock of birds in this way: “The birds left off their daily doings; the Lord’s diminutive laborers flew off in silence toward their little homes, grown quiet, just like humans toward eveningtime.” In Seiobo There Below, Krasznahorkai favors the microscopic: “… this hunter, it leans forward, its neck folded in an S-form, and it now extends its head and long hard beak out from this S-form, and strains the whole, but at the same time it is strained downward …” and on he goes for another page and a half. In this way, he both affirms and subverts his Hungarian habit for accumulation.

In a 2012 interview with Guernica, Krasznahorkai said, “The disciplined madness has its own speed, and this speed leads my characters from the possibility of terror to the very edge of terror itself.” This teetering is immediately apparent in Destruction and Sorrow, in which Krasznahorkai adds a curious twist to his reportage by using a deeply opinionated third-person omniscient narrator to relay the experiences of his alter ego, a poet named László Dante, and his companion, “the interpreter.”

The first quarter of the book chronicles Dante’s intensely observed pilgrimage to Jiu-huashan, located in Anhui, an eastern province of China, and one of four sacred Buddhist mountains. The book opens with a pessimistic stream of consciousness: “There is nothing more hopeless in this world than the so-called south-western regional bus station in Nanjing on May 5, 2002, shortly before seven o’clock in the drizzling rain and the unappeasable icy wind…” The irony here offers an antidote to the weighty title. Dante’s garrulousness offers humor, too, as if he is saying, “There’s nothing more hopeless than this one single moment in time, and it will pass.” But in the meantime, he will go on.

Krasznahorkai painstakingly describes the claustrophobic bus trip from the city, the uncharacteristically cold day in May, and the fog that shrouds the mountain. The word “grimy” appears many times in this section; until Dante finally reaches a workshop in which “that wondrous Shakyamuni was made,” he is intermittently discouraged and amazed by the “unknown fog.” When he meets the atelier master, though, he’s “possessed by a kind of cloudless gaiety, like someone who is overcome by impishness…” Dante seeks but also refutes closure, comforted by his conversation with the master and later, as they travel back down the mountain, with a porter. But after all this, he is “lost in the fog.”

The last three‑quarters of the book contains a series of conversations with officials, poets, calligraphers, museum directors, and managers of public historic gardens. Dante seeks to reconcile classical China to what he fears is an intellectual apocalypse, a decline into “the world’s most dispiriting glittering department stores,” and “aggressively nauseating Chinese pop music.”

He views Buddhist temples, monasteries, and museums as “counterfeits … in the name of reconstruction.” The book’s raison d’être might be found here, during a conversation with the poet Tang Xiaodu:

[Dante] sees this last ancient civilisation, this exquisite manifestation of the creative spirit of mankind, as dead, and he is afraid that apart from Tang Xiaodu there is no one to really talk to about this, and he is afraid that there won’t be anyone to talk to about this, because his experience is that people consider exactly the opposite to be true, and celebrate the renewal of Chinese traditions in cultural monuments restored in the most dreadful and coarse ignorance, or their attention is engaged exclusively by modern life, and are altogether unconcerned with that which was, even if it has passed, their own spiritual tradition.

Dante visits cities around the country, including Hangzhou, Beijing, Shaoxing, and Zhejiang, among others. But he has no interest in playing amiable travel writer. Dante is largely distraught, and the book unfolds as a sort of rat-race quest for the remaining glimmers of classical Chinese culture. All of this is done up in lengthy gripes about modern Chinese culture, technology, and the accelerating speed of consumerism.

His single-minded search provides the fuel for a curious range of observations. When he’s bored or overwhelmed, he skips over details, summing up his visits to landmarks with phrases like “the terrible onslaught of banalities.” But when he gets excited, a certain hush blankets the sentence with meditative repetitions, as it does here when he feels a whiff of contentment: “That is to say today, exactly today, and today it is exactly Wednesday, his questions have all run out, and so now that there are no questions left within him, with these having died away he begins to sense that where the questions have ceased to be, something else is beginning, something which perhaps could be designated as perfect immediacy.”

In all his discursiveness, Dante is rendered speechless by overpriced museums and monasteries turned amusement parks, cartoonish little Buddha statues for sale, and the overall avaricious sheen. He’s unafraid of expressing dissatisfaction, and ironically, speechlessness. His exasperation sometimes feels redundant, but his insatiability is a sight to behold. After so many days, he even tires out his translator. In a moment of rare cheerfulness, “Dante tries to whip up some enthusiasm in the interpreter in the hotel room, who, however, just once again collapses dead tired onto the bed.”

Dante confronts many officials and fellow writers with his grievances, including the diminishment of classical Chinese literature, lackadaisical government, the curiously apathetic literati, the oblivious general public, and bland educators. When he and his translator visit the Guoqing Si monastery, they consult with the abbot about the “confusing multiplicity of the remaining texts” of Chinese Buddhism and the manifold strands of Chinese Buddhism. What would the Buddha think of the varied interpretations? During their conversation, a secretary rushes in and rushes out, interrupting with phone calls for the abbot. Instead of answering Dante’s question, the abbot gives them a history lesson on the monastery and, eventually, an unsatisfying response. “There is no point,” Dante says.

Countless other sojourns can overwhelm those unfamiliar with China. Rarely does Dante, in his frustration, take time to ground the reader with the immaculate details of the first section. In this way, Destruction and Sorrow reads more like spiritual reportage. Dante’s genuine eagerness makes him seem both young and old—young because he’s so fueled with outrage and with passion, old because he’s often cranky and quick to dismiss contemporary culture. Destruction and Sorrow isn’t a book for anyone interested in a panoramic view of reform‑era China. (For that, look no further than Evan Osnos’s Age of Ambition or Peter Hessler’s wonderful China trilogy.) Rather, Destruction and Sorrow is an insider’s lament, a devotee’s quest gone wrong and then right and then dubious. Does Krasznahorkai via László Dante ever find what he’s looking for? “If you correct your mind, the rest of your life will fall into place,” says Lao Tzu. This is what Krasznahorkai’s journey, surprisingly, ultimately becomes: a journey of reappraisal.

War & War first appeared in Hungary in 1999, Destruction and Sorrow in 2004, and Seiobo There Below in 2008. Stateside, we’re receiving Destruction and Sorrow after, rather than between, the two. But Destruction and Sorrow makes much more sense after War & War, a psychologically claustrophobic book that explores war-addled entrapment. But Seiobo There Below marks a dramatic shift. We see a Japanese goddess looming over numerous artists and their art. Lush descriptions of nature, water, and abounding metaphysical beauty sing with a sublime grandeur, showing him at his most precise and optimistic—if one can call it that. Destruction and Sorrow offers a dose of redemption in limbo, a despondent parody that teems with the same soul-stirring incredulity of the Inferno, only Krasznahorkai’s hell is above ground. The ever-lurching prose collects mental detritus along the way, piling on any number of anxieties, but the pinpricks of optimism allow for a certain relief his earlier work lacks. It requires a right mind—and a sympathetic ear—to endure it. I recommend the sandwich method, reading War & War, Destruction and Sorrow, and Seiobo There Below as a sort of existential trilogy, one that moves from dread to purgatory and finally, to the sublime.

In the US, we can’t seem to get enough stories about adultery, or coming-of-age, or the recovery of memory, where the character reaches back through trauma to discover something redemptive. It’s not that these aren’t legitimate concerns, but when compared with the work of Krasznahorkai, with Sebald, with Doris Les-sing and Marilynne Robinson, they seem much less urgent. Voices can blend together; schools, too—the minimalists, the dirty realists, etc. But Krasznahorkai’s unique vision, his willingness to look outward and turn sharply away from the navel, and his indefatigable searches for the real, ultimately catapult him onto a world stage.

Is Krasznahorkai strange? Yes. Demanding? Absolutely. But he offers a refreshingly un-American perspective. You won’t find any domestic realism here, no embittered wives traipsing across town to find their cheating husbands, no couples quarreling as the baby cries in the next room, no professor-pupil affairs splitting apart families. Rather, you’ll find a bold artist who bends convention and presents a universe so slanted and strange that it’s difficult, once committed, to look away.