Nothing helps. There is no magic amulet, no proven talisman that will bring words out of the air, filter them through me and out through my pen onto the page. There is nothing that will make me write better words, somehow, exactly-what-I’m-looking-for words, than those that I might eke, squeeze, power (oh please!) out of myself without help.

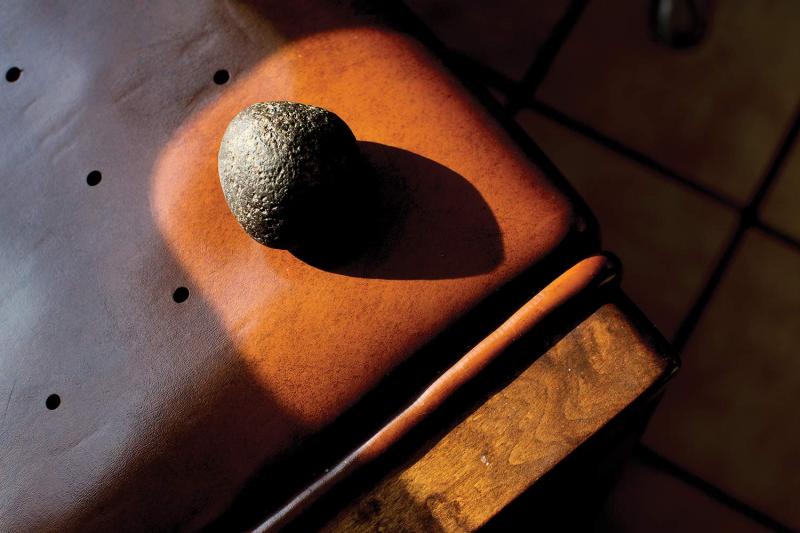

Then why is my desk so littered with stuff? What is it all doing there? Some of these objects have been there from when I was beginning my first novel nearly thirty years ago and some even longer. This rock, for example. Spheroid if not quite perfectly round, the size of a large lemon, smooth but with a pigskin’s pebble-grain texture, blackish, and heavy as iron. Originally lava from a volcano, or a meteoric fireball from outer space, hurled into the Guatemalan mountainside where I found it sometime in the early 1980s, hardened into cold stone. I hold it in my palm, lightly bouncing it, like a pitcher weighing his next pitch, staring in at the page. The trio of jaguar figurines, collected at different times over the years, word-hungry hunters who silently prowl my jungle of anxiety and nerves. The machine-gun bullet that a Sandinista soldier pulled from a bandolier draped around his torso and handed to me when we were on patrol along Nicaragua’s northern border is not something I attach a particular meaning to, though it has also stood atop my desk for many years. I like to see it there and also to hold it, jabbing my thumb against its lethal spire. A small photograph of my dad holding me in his arms, next to a small headshot of my late wife, Aura, when she was also three or so, a juxtaposition of photos I treasured when she was still alive because it showed how alike we looked at that age, chubby-cheeked, dark-eyed, smiley, assuring us that our child was also going to look like that, the adorable child we never had our chance to bring into the world. A toy soldier from my childhood, a medieval knight, actually, in silvery mail and helmet and yellow tunic. I remember the day I bought it—I was ten or so—in a Guatemala City toy store, its paint moist in the rainy-season humidity of the store, smudging my fingers. He came home to Massachusetts where, in epic battles waged in our basement den that went on for days or even weeks—my first novels, I like to think—despite being a medieval knight, he triumphed over warriors of all centuries, some also painted but the majority monochrome plastic peons, Revolutionary and Civil War soldiers, Nazis, World War II GIs, and so on. In one hand he held a shield, yellow with a blue cross, and in the other a sword. His sword-wielding arm is missing now, and the one that held the shield is severed at the elbow, because although in the basement I could direct his heroism and keep him safe, in outdoor battles in backyard loam piles or in nearby woods he was as vulnerable to flung rocks, firecrackers, and cherry bombs as all my troops. He was no ordinary soldier; even without visible arms and weapons, he was an even greater superhero than Thor. His name was Donny. I don’t know why, I guess I just liked the name. Go fight for me, Donny. Skewer some words with your invisible sword and bring them back, bloody and wriggly. Donny stoically stood his ground on quaking pine desktops as the old Olivetti typewriter rattled toward him like a slow tank, motored by my pounding, and witnessed succeeding generations of desktop computers and laptops; but mostly, from the start, he has observed me bent over the tablets of lined paper—usually yellow, sometimes light green or gray when I can find them—on which I write all my early drafts, until something, a finally achieved immersion that wants to gallop, propels me to the keyboard.

Every book generates its own special way of living with it during the years it takes to write. Most of The Divine Husband was written in Mexico City, and during those years it was almost unthinkable for me not to cap off the work day with a visit to the gym, a spinning class usually, during which I’d try to get myself into a sort of rocking-horse trance over the novel, after which I’d head alone to my favorite cantina for a tequila. That first tequila would reliably induce a state of lucid concentration, during which I’d write in my notebook, notes about what to work on tomorrow, or sentences that I’d already begun shaping at the gym. That state never endured into the second tequila, when it would be time to seek out my friends. The next book I wrote was also mostly written in Mexico City, but by then I was living with Aura and no longer went alone to cantinas in the evenings. Every book I’ve written has had its guest totem as well, something that accompanies me only until I’ve finished that book. Though when I remember my first novel, which I began in my late twenties in Guatemala City and finished seven years later, the only objects that come to mind—apart from the rock, already with me there—are cigarettes, thousands upon thousands of cigarettes. Also the paper bags a physician ordered me to hold over mouth and nose to breathe in and out of in order to subdue the panic attacks that went away, never to return, as soon as I’d finished that book. For the second novel, I hung a nautical map of the New York harbor over my desk, and so on. During the years after Aura’s death, when I was writing about Aura and about us, her wedding dress, torn at the hems from that night of dancing until dawn, hung over the tall floor-to-ceiling mirror in our brownstone parlor-floor apartment in Brooklyn. No other of my talismanic objects has ever been so intimately related to the writing of a book as that one was, for I was possessed by the idea that what I was doing, in recalling Aura in words, in trying to bring her words back, in trying to bring Aura back in stories, was filling that dress up with words, believing it to be like a cabbalistic search for the right sequence of words to strike the spark of life, and that if I found that sequence I’d walk into that room and find Aura restored to life like the statue of Queen Hermione in the last act of The Winter’s Tale, standing there in her wedding dress and wondering why she was wearing it.

The rock, the bullet, the word-hunting jaguars, the toy knight with his invisible sword, the photographs: These are on my desk in Brooklyn.

But often I am not in Brooklyn, and over the last few years have spent more time in Mexico City. What accompanies me everywhere I go is my physical restlessness—it’s simply hard for me to sit still. Nervousness, anxiety, sometimes terror, even my dyslexia, are all components of that restlessness. The struggle to wrestle myself into a state of physical composure and concentration is, for me, the struggle to write. I ask the rock to be like a paperweight on my fluttering nerves. Cigarettes, alas, used to work wonders, every deep inhalation toxically pinning me down. For several years in Mexico City I lived in Colonia Condesa, near Parque México, which has an avenue running in an oval around it. That avenue has many cafés, and I was able to master restlessness by starting my writing day in one café, after a while moving on to the next, and then to the next, counterclockwise all around the park, from one cup of coffee or glass of juice to the next, until I’d circled the park and finally felt settled enough to head back to my apartment to continue working.

Of course Aura’s sudden death six years ago at age thirty changed everything. A giant boulder of reality was rolled into the path of that part of my imagination that used to make things up, that sought meaning in fantasy, in the fictionalizing imagination’s transforming of reality. I wrote my book about Aura, and then another, recently finished, in some ways a sequel to the first. Finally I was ready to return to the wholly fictional novel—much changed now, of course—that I was working on when Aura died. To me, fiction still seems as essential to life as laughter. But maybe I’ve never before felt so frightened of the empty page as I do lately, so nervous, anxious, and restless. I recently heard Richard Ford define talent as “a species of vigor.” Restlessness, fear, and nerves can be a kind of vigor, generating an energy that has to be put to work.

But before I can get back to that novel, I have to write this essay. I circle the block, walking around it once, twice. These special things I’ve kept on my desk for so many years, they’re like private secrets and heroes. I don’t have my rock with me, but I feel its weight. Jaguars prowl, and Donny raises his invisible sword. The words suddenly come, “Nothing helps. There is no magic amulet, no proven talisman …”