Cococi, a small town in the Brazilian state of Ceará, was once part of a thriving cattle industry, populated by cowboys and wealthy landowners, and owned by a single powerful family—the Feitosas—whose descendants continue to influence politics and businesses in northeast Brazil. By 1970, a family feud, exacerbated by drought, led to Cocosi being mostly deserted, and today the town serves as a symbol of the region’s economic struggle.

The bush cowboys of Cocosi—known as vaqueiros—are, like others in northeast Brazil, an endangered profession, facing pressures both natural and man-made. Drought, modernization, and societal shifts have whittled away at various artisanal professions of this region, trades born out of necessity and reflecting a rich, multifaceted culture.

Rafael de Araujo Feitosa, shy at thirty-six, with a slight frame and blue eyes, is one of the last of the working vaqueiros in Ceará. Though he shares the name of his powerful ancestors, he possesses none of their former wealth. Meanwhile, the cattle skulls scattered across the ranch are a reminder that his days as a vaqueiro are numbered. With little food and water, the cows that remain won’t survive long.

According to Rafael and other cowboys, it isn’t just the drought that threatens his profession. “The cows here were originally made to run wild over vast expanses of treacherous land,” Feitosa says. “As land was purchased, ranch owners corralled their cows into much smaller plots with fences, and so the animal’s wild nature has been tamed over time. Now you can be a cowboy with just a motorcycle and jeans.”

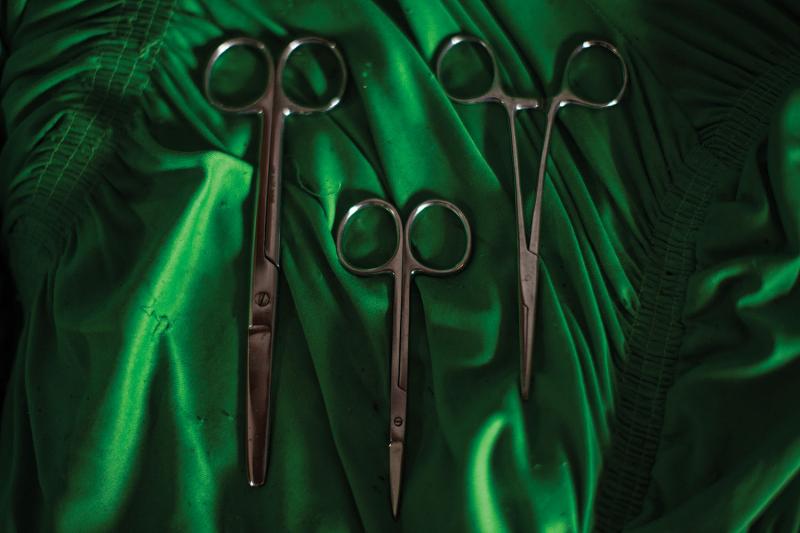

And as the vaqueiro fades, so do the trades that have evolved around him. Seleiros—artisans who craft saddles and the cowboys’ leather gear to protect them from the thick, dry brush that covers the valley—are one example. Espedito Veloso de Carvalho, one of the most well known seleiros in the region, comes from a long line of cowboys and leather artisans. His grandfather was said to have outfitted Brazil’s most notorious bandit, Lampião, as well as his entire gang. With traditional work disappearing, Carvalho has evolved his family business into a brand that includes high-end bags and sandals. He appears to be the exception, since the majority of leather makers in the northeast eke out a living dressing rodeo cowboys and repairing women’s shoes.

Unpredictable climate, unsustainable practices: While the fate of certain trades might seem like a cautionary tale, other artisanal traditions in this part of Brazil are succumbing to a more powerful, and arguably inevitable, phenomenon—modernization. The work landscape in the northeast has been radically transformed by its effects—from a more sophisticated stewardship of resources to improvements in technology. Industrial advances and environmental restrictions have reduced the number of Brazil’s salt miners, and the global marketplace has squeezed the country’s iron-ore workers, who find themselves displaced by an overabundance of cheaply made tools competing with those they’ve made for generations. Midwives, too, are in less demand as hospitals have become more accessible and offer the increasingly popular option of giving birth by cesarean section.

As a matter of survival, some artisans have reorganized themselves and their approach to their trade. One example is the Academy of Cordelistas in Crato, currently run by poet Luciano Carneiro. This academy is dedicated to preserving the tradition of the cordel, a booklet written by poets and illustrated by block-print artists, which evolved from an oral tradition of disseminating news and social issues to a mostly illiterate public, carried over from eighteenth-century Iberia. As various forms of media have reached the backcountry, the cordel has evolved from a news source into a collector’s item, an artifact of sorts. Yet block-print artists such as Carlos Henrique and poets such as Carneiro hope that by formalizing their tradition they can find a way to preserve it. “The loss of popular culture has caused people to live their lives through television instead of living life in the streets,” Carneiro lamented. “However, the cordel has already survived the birth of the radio, television, and now the internet. So I know it will persevere.”

— Nadia Shira Cohen