American culture is in a moment of reckoning. With the Women’s March, #MeToo, and Black Lives Matter, there has been a demand for greater accountability among the powerful, and an insistence that we pay close attention to privilege and its blindspots. This gut-check has extended beyond the realm of civil rights to encompass repairing the historical record. This past March, The New York Times began “Overlooked,” an effort to rectify an imbalance in its own obituary coverage since 1851. “Who gets remembered—and how—inherently involves judgment,” noted Amisha Padnani and Jessica Bennett in their introduction to the project. It all comes down to the chroniclers, the gatekeepers.

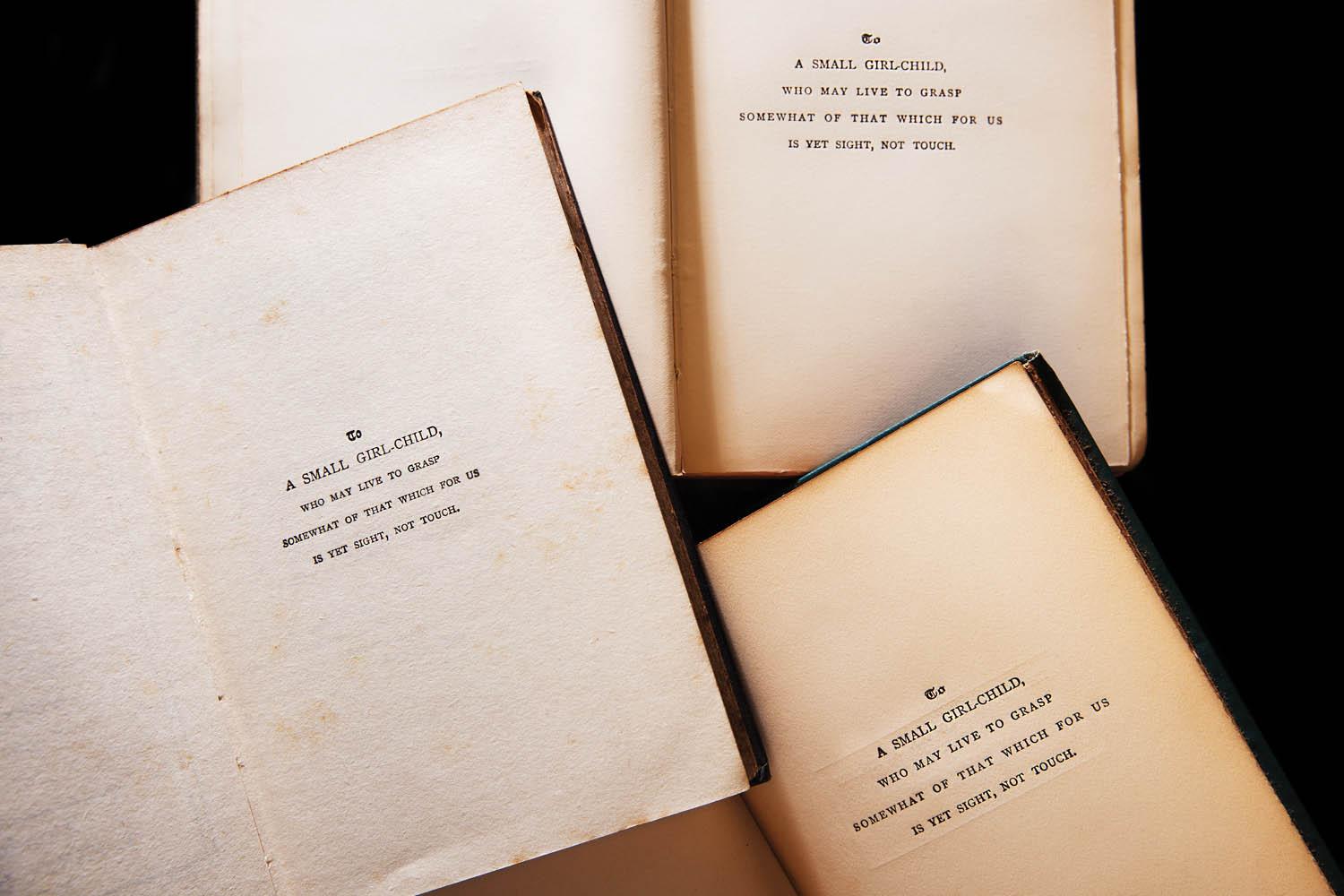

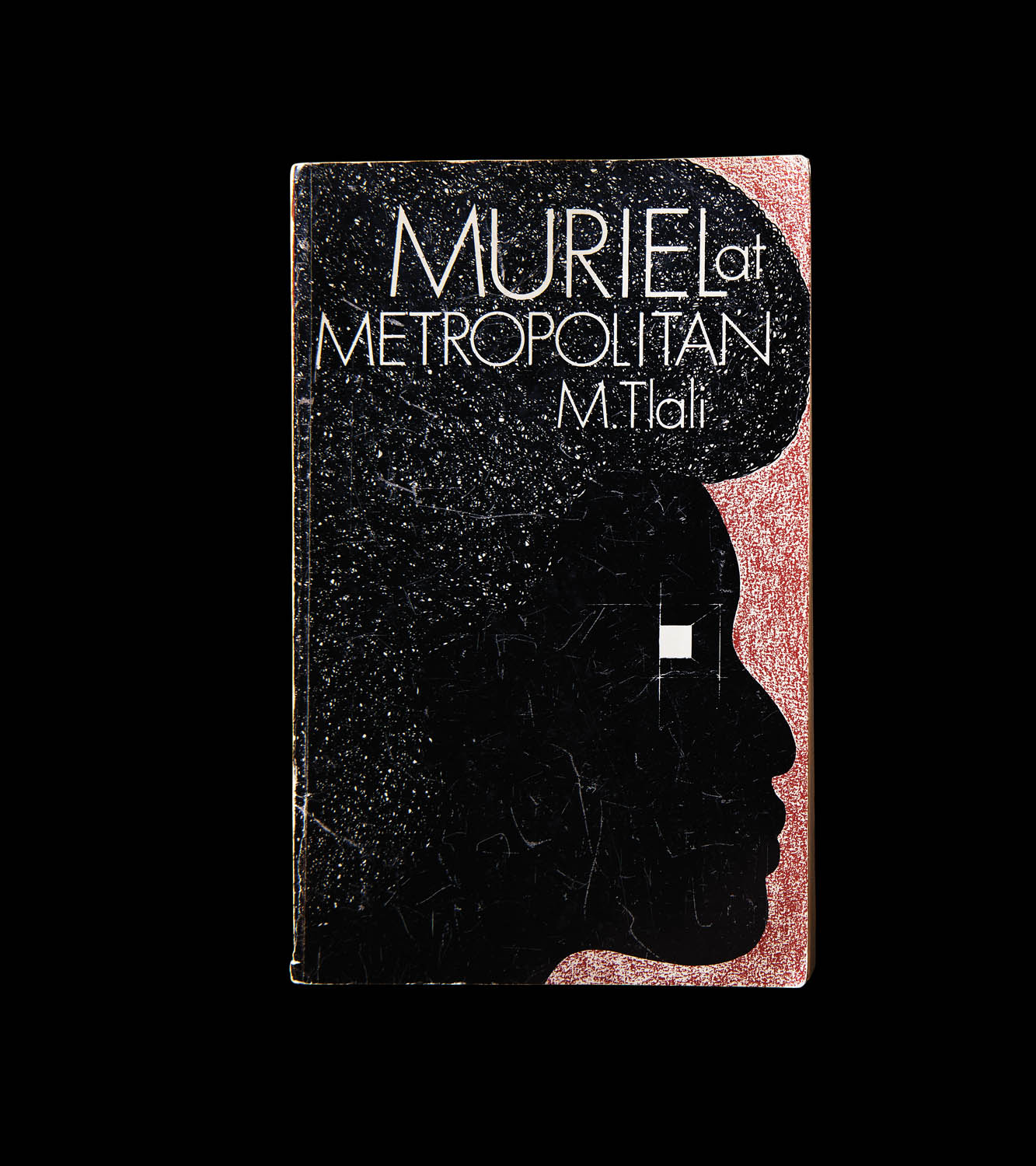

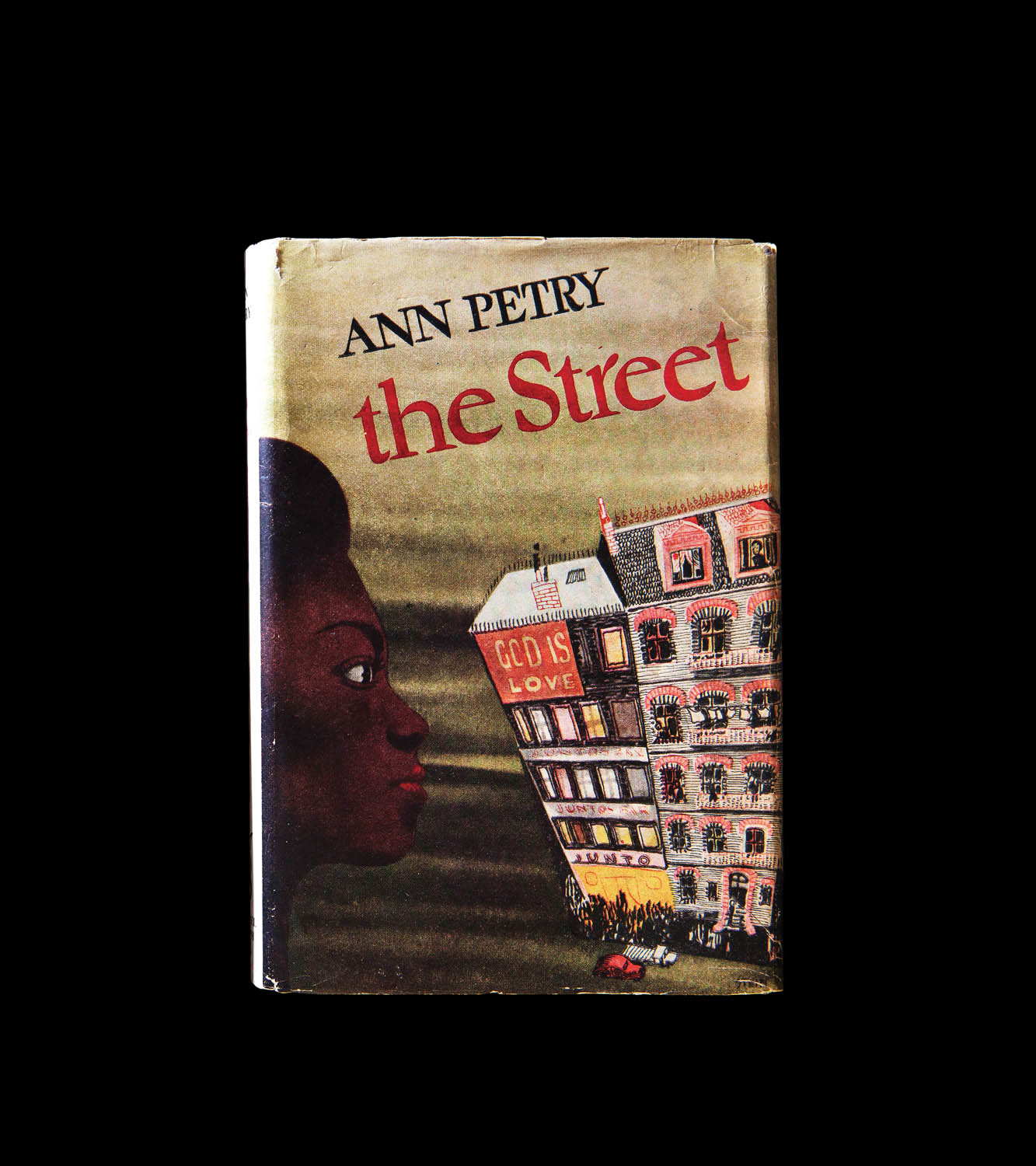

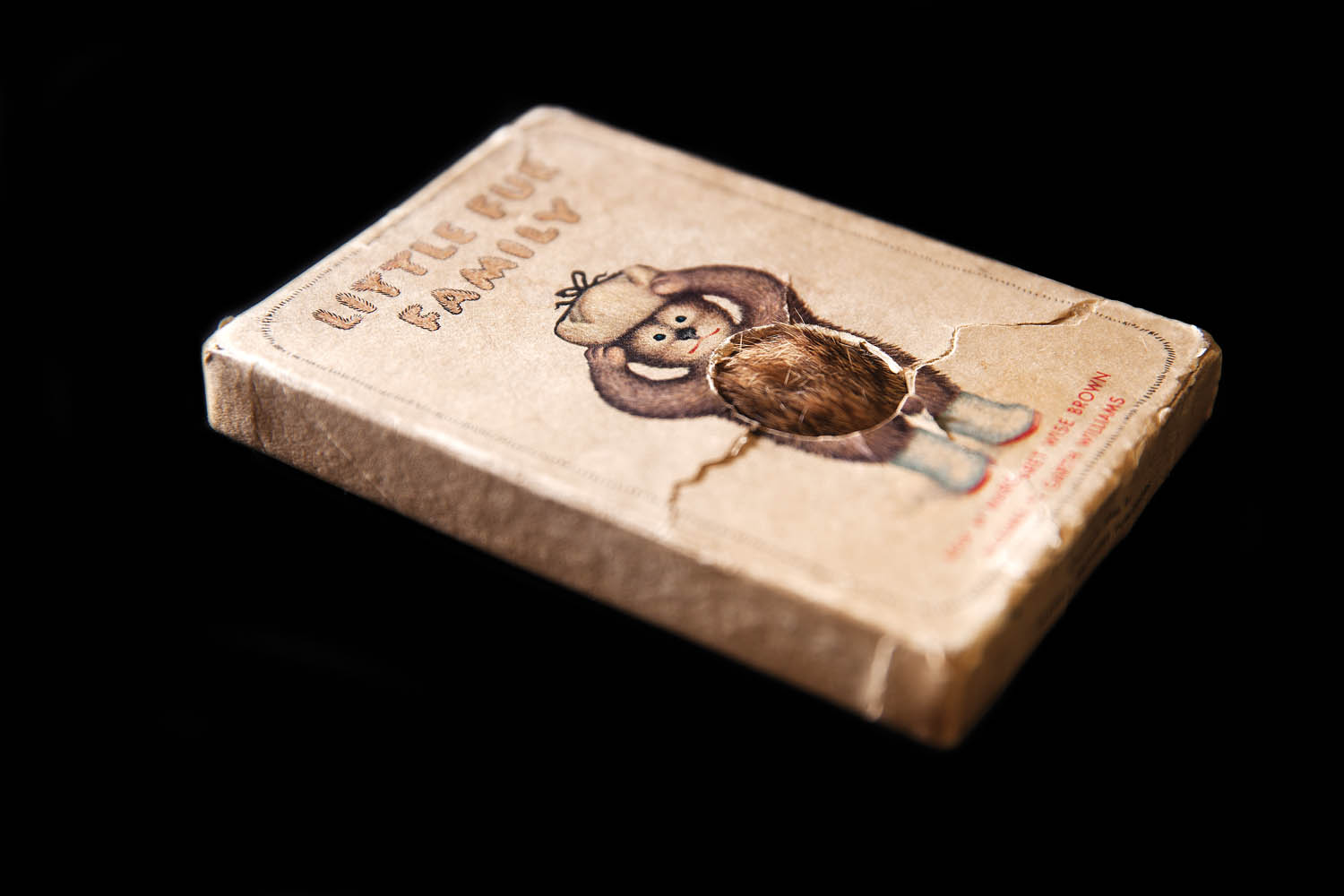

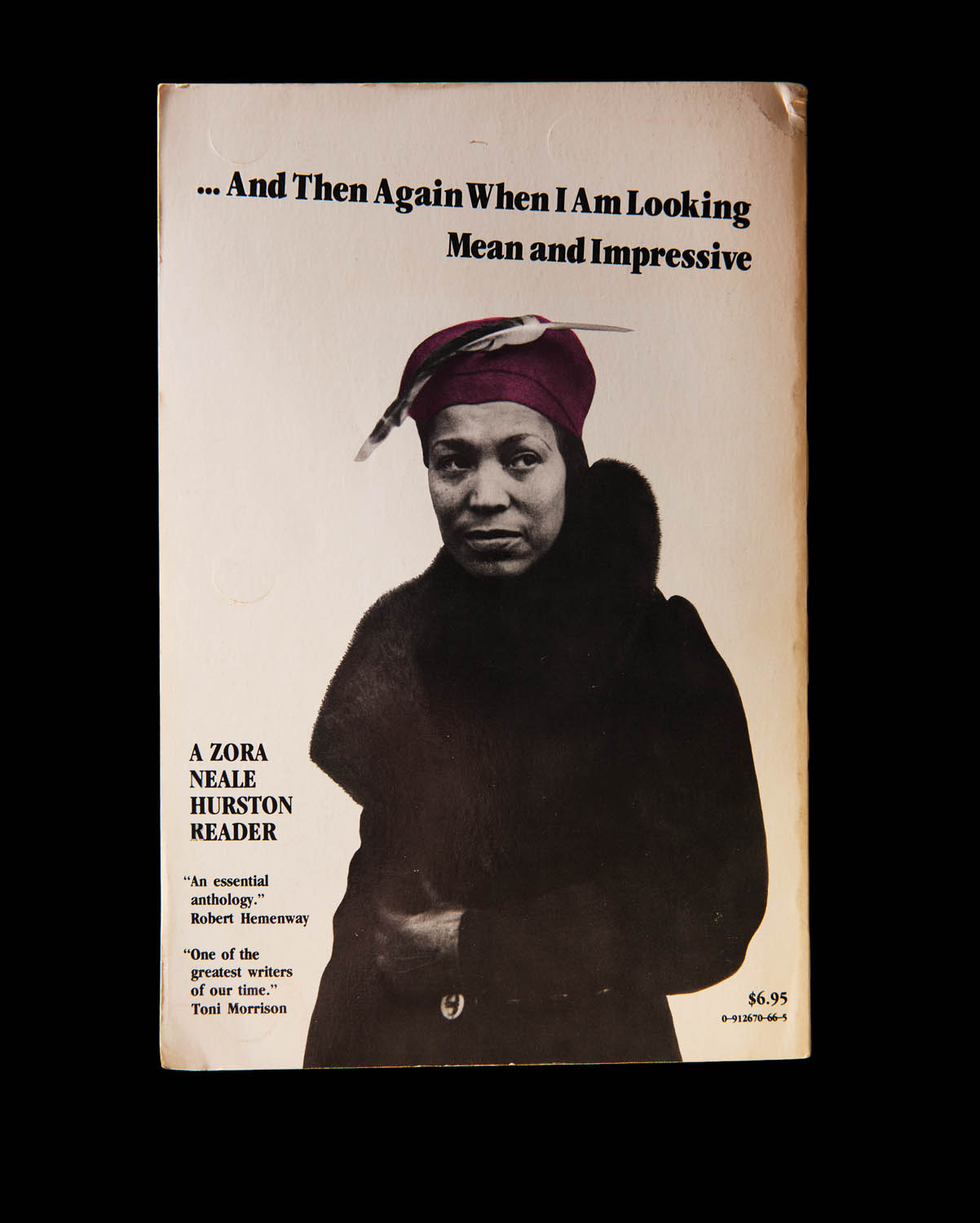

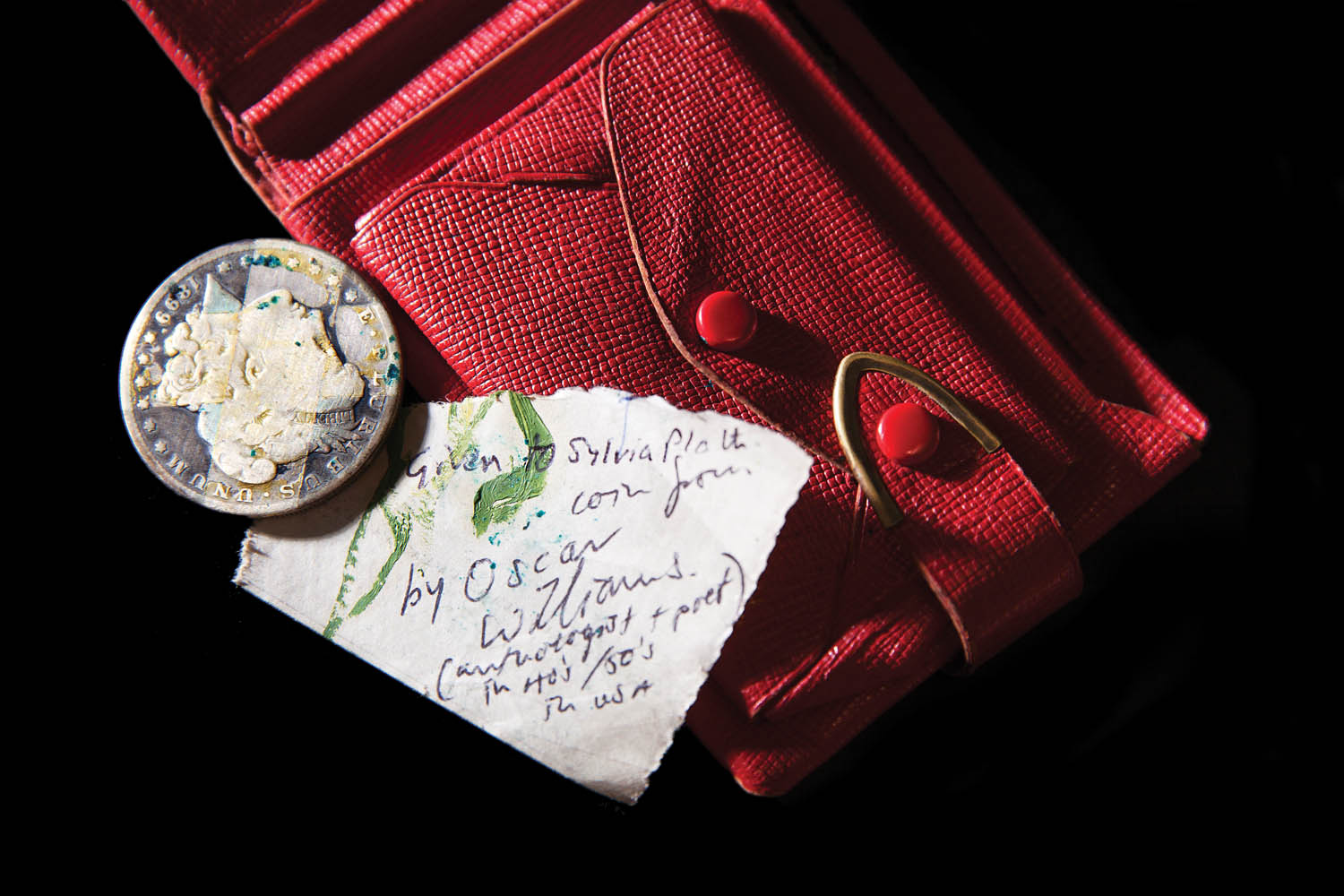

Until recently, much of the history made by women and people of color went unrecorded, preserved instead in unconventional ways. That’s because men—most often well-educated white men—have traditionally served as the arbiters of taste, with many of our cultural institutions founded on their arbitration. Since the contributions of women and people of color have not been regarded the same as those of white men, neither has their work. This exclusion, which easily leads to erasure, is felt acutely in the rarefied world of book collecting.

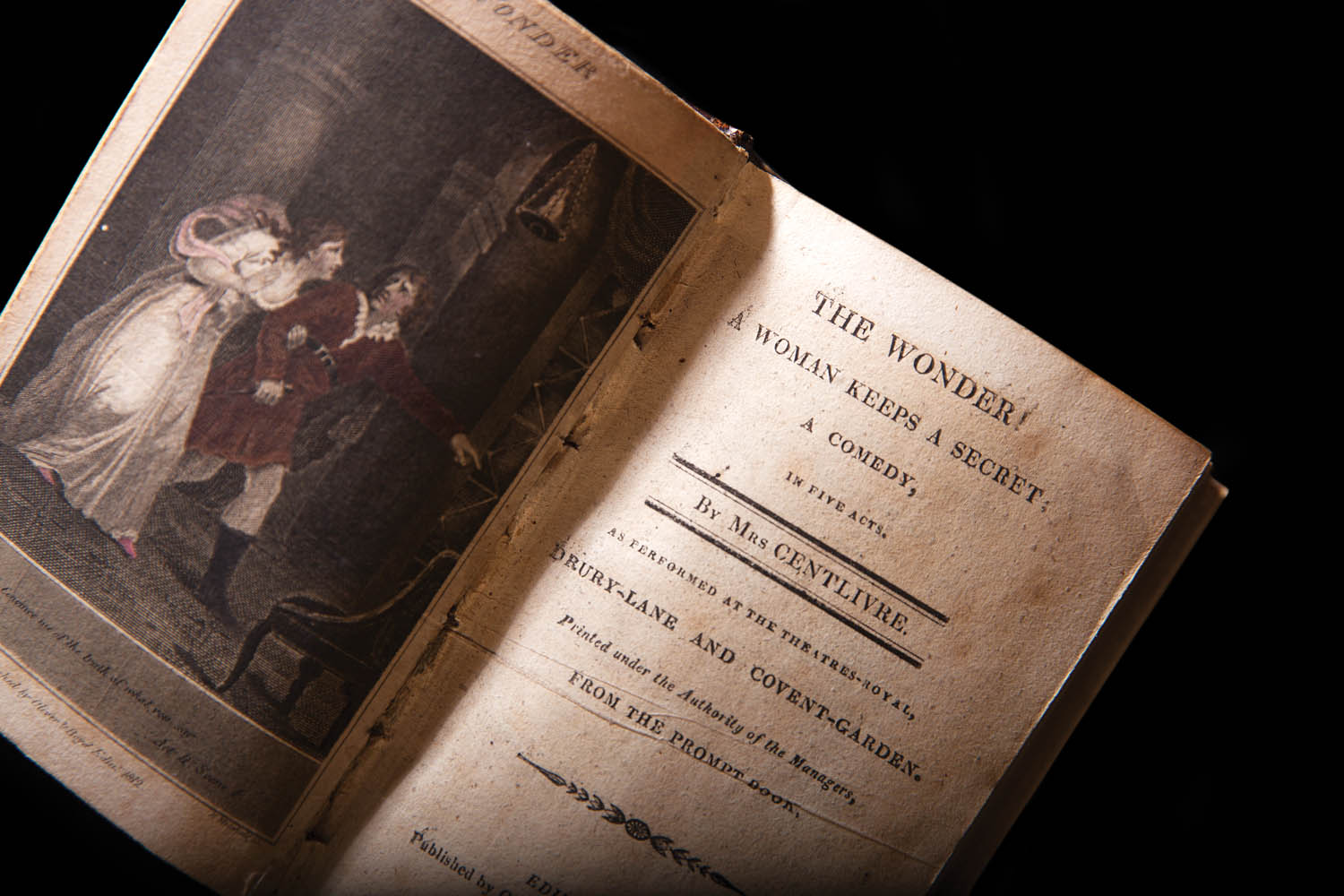

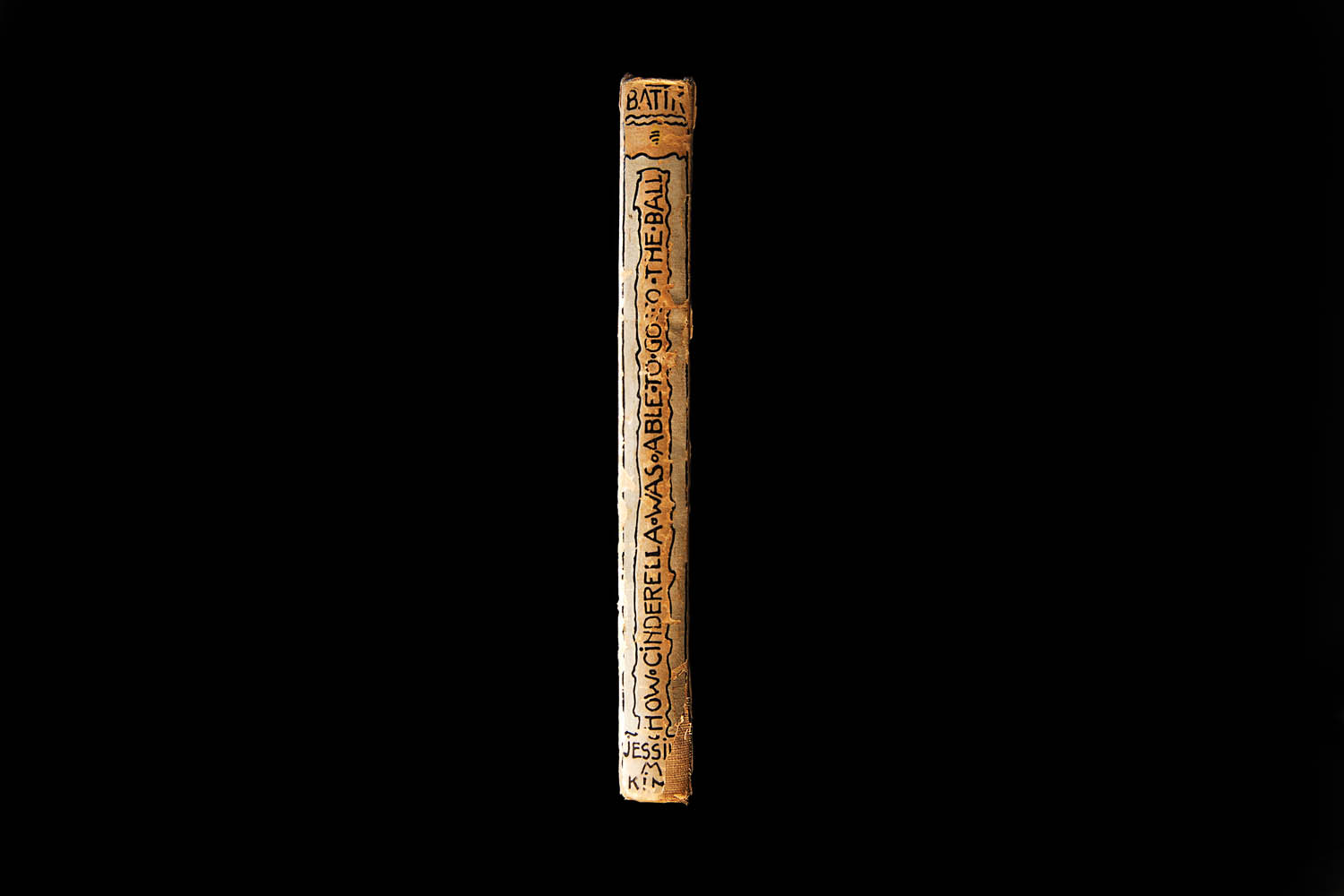

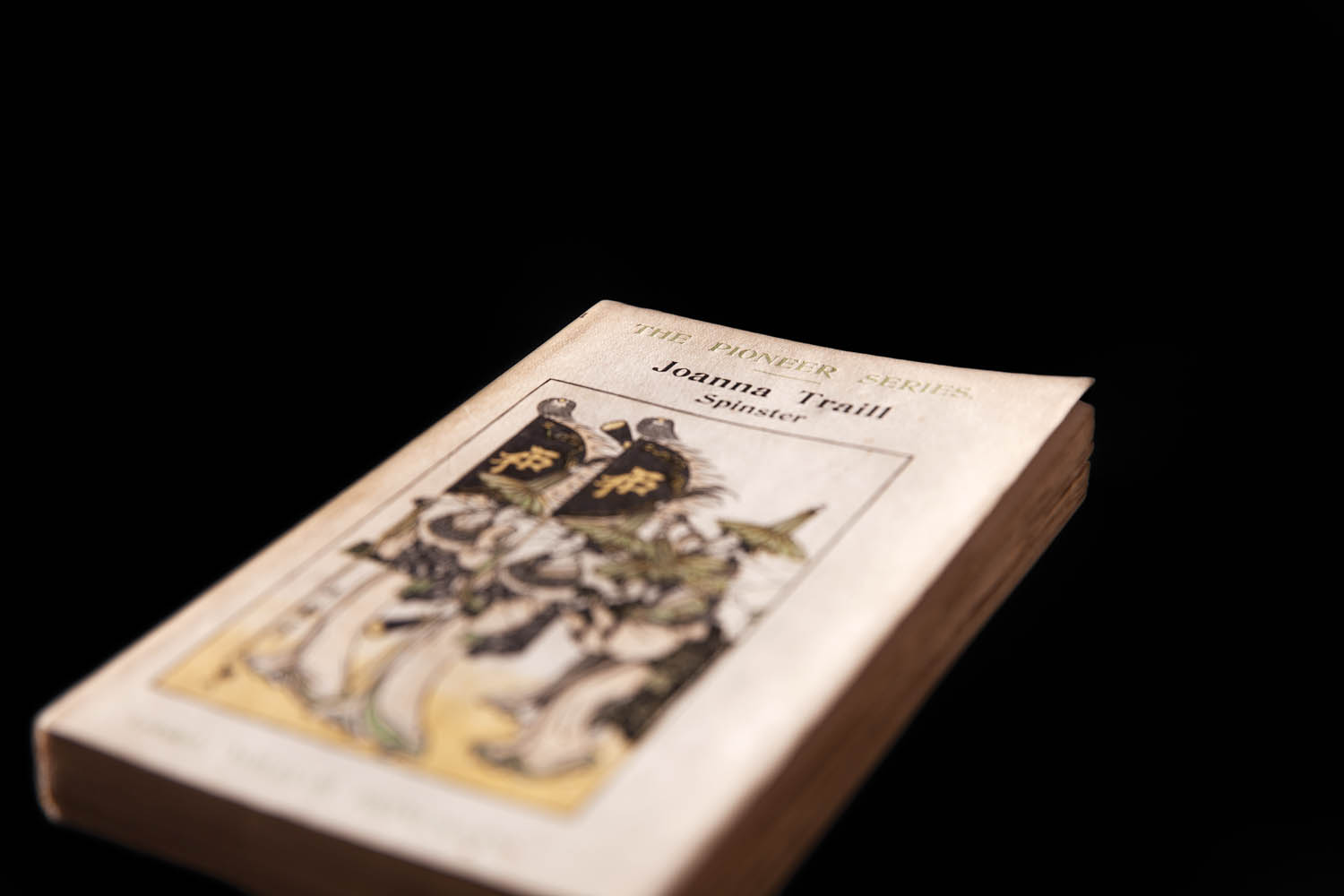

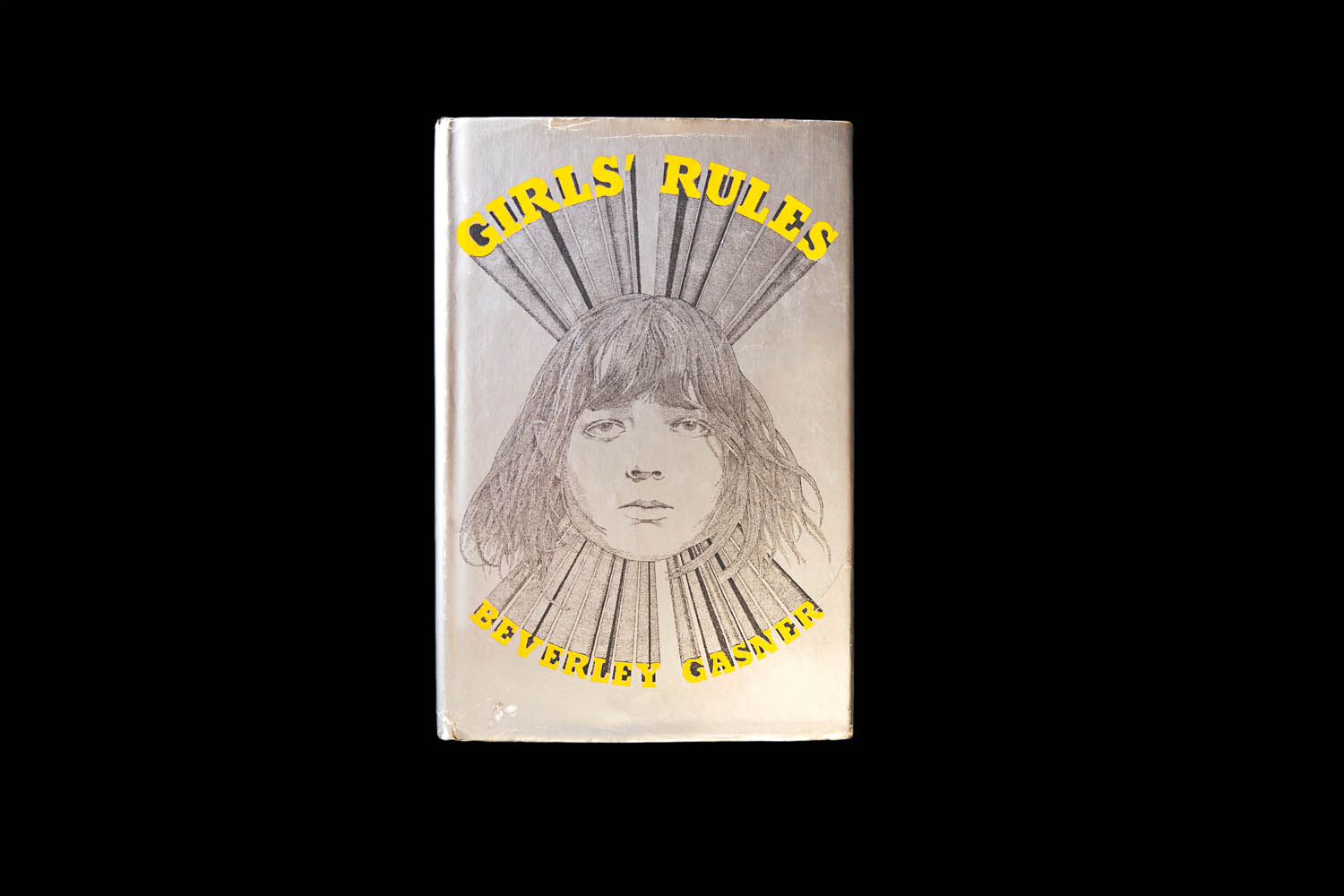

“When I look through rare book catalogues,” says A. N. Devers, a writer and rare-book dealer who focuses on women’s writing, “most of the books in them are by men. It’s a common occurrence for there to not be a single book by a woman.” Time and again, Devers has browsed such catalogues—the primary tool book collectors, librarians, and archivists, from both public and private institutions, use to build collections—and found that, despite their length, they often contain no work even about women. “The implication,” she says, “is that women didn’t write books, or that their books aren’t good.”

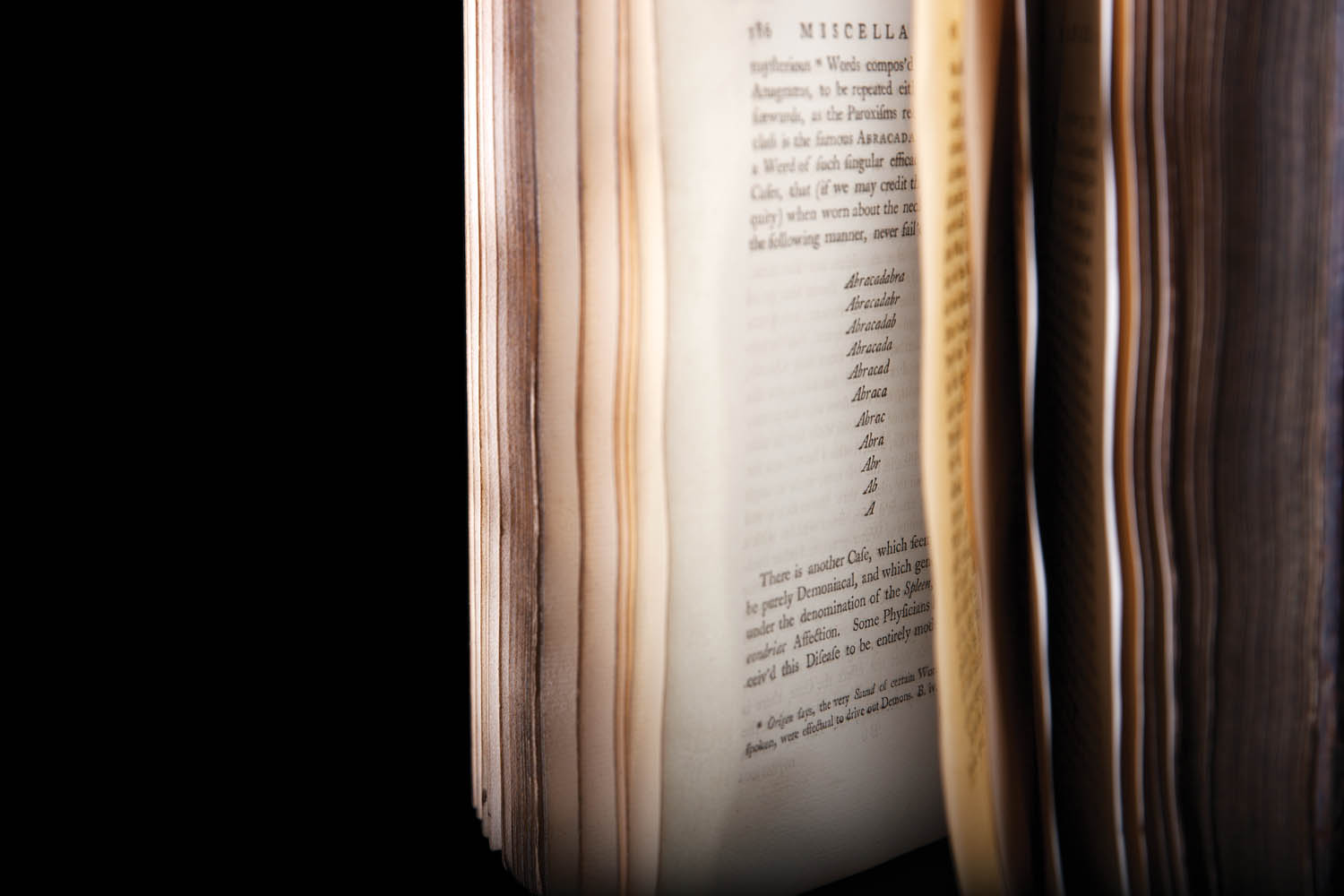

This omission has practically guaranteed that women’s literary contributions aren’t fully represented in research and educational institutions. Even if their work appears on the shelves, says Devers, women have by no means enjoyed the same validation by the influencers of culture. Devers references The Book Browser’s Guide (1975), a popular reference book about Britain’s secondhand bookshops, by Roy Harvey Lewis. In it, Lewis describes the experience of going to a secondhand bookshop as one of seeking “nourishment.” In ruminating on the readers who don’t seek nourishment, Lewis says,

Nor can we be much more explicit about the type of people who browse, except possibly in one respect—their sex. The significance escapes me, but nine browsers out of ten are men.

It would be monstrous to suggest that women do not buy and read as many books as men, but undoubtedly they have a different approach to buying. A woman tends to know what title she wants, and it is unusual to see her browsing. Why? A less traditional trade would commission a market-research survey in which motivation was carefully analysed. Meanwhile, one can only speculate. Women might claim they do not have the time to spare but this hardly rings true, and many women actually check the browsing habits of their male companions. … Mind you, just as some husbands believe it is their God-given right to spend the bulk of their earnings in the pub or betting shop, one can appreciate the anxiety of the woman whose partner is a bibliomaniac, even housekeeping money being turned to feed this passion.

Is it any wonder that books by women are often undervalued in the rare book trade? The centuries-old word “bibliomaniac” is a male construct that excludes women, as does the popular “bookman,” a much older term used to describe rare book dealers and collectors alike. As a woman in this commercial niche that has been skewed toward male dealers, male collectors, and male authors for centuries, Devers resents the implication that women might not be able to collect in the same way that men do because they “must not seek nourishment.” In fact, she says, as an agent in this trade, and in bringing a wide range of work by women together on the shelves, where they are now “in conversation,” she is engaged in an “act of nourishment.”

—Allison Wright