Claudia Emerson, who died in December 2014, had come to be known as a poet capable of revealing startling discoveries inside quiet, quotidian circumstances. Her poems are set mostly in Southern rural and small-town scenes, moments in ordinary lives that would normally elude anyone else’s attention—a woman straightening her hair before a mirror, or finding amid old photographs the daybook of someone else long gone; watching patterns that starlings make as they flock, or listening from inside a house to the sounds of horseshoes being thrown outside at dusk. Emerson’s work captures in such situations the “surrealism of everyday life”—a phrase of Elizabeth Bishop’s. Bishop suggested that there is no distinct “split” between the ways consciousness and subconsciousness work in art, and she referred for example not just to dreams, but to “unexpected moments of empathy” and “glimpses of the always-more-successful surrealism of everyday life,” which “catch a peripheral vision of whatever it is one can never really see full-face but that seems enormously important.” Emerson’s concentrated yet receptive observation is equally concerned with what can’t quite be seen “full face,” and she could almost stand in for Darwin in the illustration Bishop offers, had Darwin been exploring the unnoticed life of the American South: “Reading Darwin one admires the beautiful solid case being built up out of his endless, heroic observations, almost unconscious or automatic—and then comes a sudden relaxation, a forgetful phrase, and one feels that strangeness of his undertaking, sees the lonely young man, his eyes fixed on facts and minute details, sinking or sliding giddily off into the unknown.” In Emerson’s method, too, one follows her exacting attention to the concrete, as well as to the metaphorical, not quite noticing at first—yet not questioning when you do—that the literal and figurative worlds sometimes coalesce in her poems. Here is “The X-Rays,” from her Pulitzer Prize-winning Late Wife’s sequence of poems addressed to the author’s husband, whose first wife died of cancer:

Claudia Emerson, who died in December 2014, had come to be known as a poet capable of revealing startling discoveries inside quiet, quotidian circumstances. Her poems are set mostly in Southern rural and small-town scenes, moments in ordinary lives that would normally elude anyone else’s attention—a woman straightening her hair before a mirror, or finding amid old photographs the daybook of someone else long gone; watching patterns that starlings make as they flock, or listening from inside a house to the sounds of horseshoes being thrown outside at dusk. Emerson’s work captures in such situations the “surrealism of everyday life”—a phrase of Elizabeth Bishop’s. Bishop suggested that there is no distinct “split” between the ways consciousness and subconsciousness work in art, and she referred for example not just to dreams, but to “unexpected moments of empathy” and “glimpses of the always-more-successful surrealism of everyday life,” which “catch a peripheral vision of whatever it is one can never really see full-face but that seems enormously important.” Emerson’s concentrated yet receptive observation is equally concerned with what can’t quite be seen “full face,” and she could almost stand in for Darwin in the illustration Bishop offers, had Darwin been exploring the unnoticed life of the American South: “Reading Darwin one admires the beautiful solid case being built up out of his endless, heroic observations, almost unconscious or automatic—and then comes a sudden relaxation, a forgetful phrase, and one feels that strangeness of his undertaking, sees the lonely young man, his eyes fixed on facts and minute details, sinking or sliding giddily off into the unknown.” In Emerson’s method, too, one follows her exacting attention to the concrete, as well as to the metaphorical, not quite noticing at first—yet not questioning when you do—that the literal and figurative worlds sometimes coalesce in her poems. Here is “The X-Rays,” from her Pulitzer Prize-winning Late Wife’s sequence of poems addressed to the author’s husband, whose first wife died of cancer:

By the time they saw what they were looking at

it was already risen into the bones

of her chest. They could show you then the lungs

were white with it; they said it was like salt

in water—that hard to see as separate—

and would be that hard to remove. Like moonlight

dissolved in fog, in the dense web

of vessels. You say now you kept them longer

than you should have, those shadow-photographs

of the closed room of her body—while you

wandered around inside yourself as though

inside another room she had abandoned

to her absence, to barren light and air,

the one indistinguishable from the other.

Within this sonnet-shaped enclosure, it’s hard, finally, to see the “she” as distinct from “her absence,” or, having entered the metaphorical space of grief, to regard the abandoned room inside the “you” as separate from “the closed room of her body.” Metaphor and object of metaphor keep shimmering and displacing each other like “moonlight / dissolved in fog,” captured in “shadow-photographs” perhaps “kept … longer // than you should have.” What’s “hard to see as separate / … hard to remove” speaks as much for the self destroyed as for what destroyed it—but not because the poem is in any way vague or ambiguous; it’s the very precision of vision and language that allows us to fully recognize the profound effects of paradox.

Quiet that triggers unnerving recognition; confinement that suggests pressure toward release: These kinds of balancing appear again and again throughout Emerson’s work, whose clarity is what allows a deeper exploration of the mysterious, as in these lines from “The Physical Plant,” the opening poem in the sequence “All Girls School,” from her fourth book, Figure Studies. The poem details the single-sex institution’s halls of “combed order”:

straightened teeth, trained spines, the chapel’s

benches in rigid rows before crimson

kneeling pillows, slim beds in dormitories,

the muted ticking of practice rooms, horses’ stalls

just-mucked, the halls humid with breathing.

And in the brushes, their hair—enough to line

the nests of a hundred generations of birds.

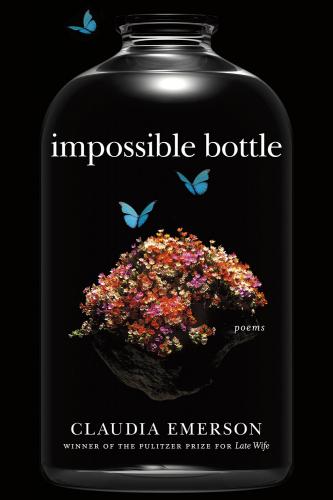

In that last sudden shift of focus one can recognize an alertness to what Emerson’s even older kin in American letters, Emily Dickinson, called “Circumference.” Emerson’s collection Impossible Bottle, published posthumously,recalls and reimagines Dickinson’s wild transformations of containment with astonishing originality. The book’s title itself brings to mind Dickinson’s fascination with paradox, and theepigraph from Dickinson—“This World is not Conclusion”—prepares for the volume’s expansiveness, which begins with intensity of gaze turned not outward but in on the self—although a self already in the process of dissolution, a self whose body is now the one through which cancer is rising, invading at last even the brain itself. Emerson’s practiced acuity of attention offers a simultaneously personal and objective sense of the effects of disease, such that the implicit question of how the soul ever got into such a thing as a body in the first place feels as natural as wondering how “the ship, a clipper, graceful and lean, its sails / pristine, the delicate // threads of its rigging … suspended, // bottled against wind and water, driftless / in the dead sea of the cupboard” ever got inside the bottle. This ship-in-the-bottle image from the book’s title poem links to another bottle in the same poem, recalled from a childhood visit “only one time” to the fearsome ocean, when the child’s mother told her

to fill a bottle with air, to steal

some away as a souvenir

to open and breathe one winter night

when my attic bedroom

window would seal me in and threaten to let me

forget that day, its perilous air.

In these couplets, the dual threats of outer and inner, of exposure and suffocation, are heightened by the lines’ many repetitions of sound, most striking in the rhyming of “steal” and “seal,” which emphasizes the uncanny containing of ocean’s “perilous air” within the “attic bedroom.” The questions of what might happen upon opening the bottle—or what might happen if the bottle isn’t opened—echo the question of suspense running through this collection as it apprehends from inside as well as from outside something unstoppable, whichever way you approach it: the advance of a metastasized cancer, recognized as “the physician // speaks to his screen instead to the all / of you it has // become”:

your sorrow is ecstatic something

you do not feel

you hear your own voice at a distance

in the abelia bush

outside at home a voiceless God

flames there late bees

a burn slow miraculous such green there

there you are

[“Metastasis: Intercession”]

Emerson’s eye, focused intently in these poems, achieves at the same time its most remarkable feat of peripheral vision, allowing metaphor and object of metaphor to reflect each other mutually—not only poem by poem, but increasingly throughout the collection. In a sustained questioning of how to resolve containment and release, the poems begin more and more to identify self with not-self: “ecstatic” sorrow becomes a source of what feels like the most natural and necessary discovery of self, and loss of self, elsewhere (“there / there you are”)—in “the bird deviant // albino the one become / sillouette [sic] cut-out” in the flock [“Metastasis: Chevron”]; in “fragile lace-like // … constellate erasures,” [“Metastasis: Worry-Moth”]; in the spider’s work accidentally torn by a wren: “the joy / such swift excision” [“Metastasis: Web”]; in the empty tree house, “a child’s afternoon / without the child” [“Metastasis: Tree House”]. As inside the self the metastatic threatens—change of position, state, or form—the allurement of the ecstatic—to be outside of self entirely—begins to take hold.

Spacing and lining often become unconventional in this final work of Emerson’s, perhaps in part as appreciation of what Dickinson’s unusual presentation meant—as John Berger has said about Dickinson’s poetry, “the presence of the eternal is attendant in every pause.” But Emerson’s opening up of lines seems also a reflection of what a radical reorganization of self feels like. “Metastasis: The James” concentrates on the river that “takes // another town’s rain into / itself for itself // swells with its snow its trash / it supplants its own // banks,” then narrows: “you will know / when all of it // recedes it will / intercede to see you see.” In these phrases anticipating death, one can hear the unforgettable last lines of Dickinson’s deathbed poem that keeps noticing a fly’s buzzing: “And then the Windows failed—and then / I could not see to see—.” Emerson is not only recalling Dickinson, though; Impossible Bottle’slooking inward to see beyond includes in the process something Dickinson tended to eschew: a sense of the ways private and social worlds interact as part of the passage between life and what may succeed it. In “The Anatomy Lesson: Resection,” the “you” undergoing surgery becomes the “lesson,” “the exam” as “the medical students / file in and listen; // they write things down.”

they can tell you, when you

return to them, what you can live without, what

regenerates, and on hearing it,

you feel a lightening, the way a snake must

on slipping through its discarded

mouth into another year, or, knowing nothing

of a year, into time itself.

The snake may bring to mind Dickinson’s “narrow Fellow” met with “tighter breathing / And Zero at the Bone”—and Impossible Bottle corroborates beautifully Dickinson’s reports from “reportless places” of “sumptuous Destitution”—but in Impossible Bottle the Dickinsonian reverberations are incorporated into a steadier kind of attention that is Emerson’s own particular examination of what being certain to die finally feels like.

Emerson’s “Metastasis” sequence, a crown of sonnets, spreads through the book’s first section, the form disappearing into longer poems, then reappearing with unexpected grace, changing according to each site where it refinds itself. Looking back through the section, attending to the sequence’s subliminal effects, is like reviewing a new series of shadowy x-rays, coming to understand their correlation. The process by which the sonnet changes position and shape in the “Metastasis” sequence is breathtaking, as form itself becomes metaphor. Something similar happens in the way Impossible Bottle’spoems widen scope, from the personal voice, speaking to itself as a “you,” slowly altering with the gradual awareness of being part of a larger voice, a voice shifting not only among first, second, and third persons, but also moving eventually between first person singular and first person plural—something that begins to take effect after the realization of the book’s second poem, “MRI,” when the technician tells the “me”

to follow the breathing directions as best I can,

and I do, for the next

three quarters of an hour, breathe in and out

and pray, curse, clench my teeth,

sorry as I have ever been for myself

and suddenly sorrier

to realize that I am the last of the many

this day; someone else’s

face was just this close to the low ceiling,

someone else’s worry

saw this flat whiteness. In my hand I hold

the small, bulbous call

button everyone must hold, with the same

nervous lightness, I can

imagine holding a moth—so as not to kill it

and not to let it go.

As the voice of the book begins opening after this to include other voices, one can hear another literary great-grandparent, Walt Whitman, begin to murmur—especially in Emerson’s remarkable “Infusion Suite.” While death took place mostly at home during Dickinson’s and Whitman’s time, dying tends for us now to be less familiar, a more prolonged and distant process, set off from the rest of life, in hospitals and hospice settings. Yet the witnessing and sharing in facing life’s end that we hear among patients and nurses in Emerson’s “Infusion Suite” brings to mind Whitman’s daily tending to the Civil War wounded and dying who couldn’t be with family during their last moments. In the twelve sections of “Infusion Suite,” patients away from home for specialized treatment, tended by nurses as needles feed the chemo into their veins, look outside the windows to see that “someone / has hung feeders to distract us from ourselves, / … Hour after hour, we watch birds circle / the plastic cylinders of sunflower seed, / cling to the caged cakes of suet swinging / from tall hooked poles—not unlike ours” [“Infusion Suite 2”]. Or they talk, in this set-apart space, as matter-of-factly about their cancer or bone-marrow transplants as about their scrabble game or their work—like Leonard, a mechanic “at the collision place, his specialty the under // -carriage of a car after a wreck, / realignment, the stuff nobody ever sees / and will never notice unless—no, until— // it gets out of whack” [“Infusion Suite 4”]. Their straightforward outward voices are woven with what we hear from the interior:

A woman I have never

seen, purple-turbaned, prefers jaundiced leaves,

birdless feeders someone forgot to fill

to any of us. I have chosen to look out

that window at what passes for the world.

We all have. What we do not know about

each other can go unspoken; our old ordinary

means nothing here, and we know already

the ordinary that this is—and is—.

[“Infusion Suite, 8”]

One can find in an earlier poem, “Atlas,” from Emerson’s Late Wife, a kind of premonition of the voice we hear in Impossible Bottle. “Atlas” examines a book “remaindered / at half price, a book many / had handled without wanting to // own”—a catalog of Orthopaedic Injuries of the Civil War, early photographs and descriptions of “particular survivals, // organized by the anatomic / regions of loss”: “some men are halved and in the next / photograph risen from ether,” surviving “the bullet, the surgeon’s knife,”

and now this first, rough reconstruction

of the body, to look past the aperture

and into the photographer, wearing

the century’s dark caul, then into me.

I bought the book, but not for their

unique disfigurements; it was

their shared expression I wanted—resolve

so sharply formed I cannot believe

they ever met another death.

The soldiers “look past the aperture / and into the photographer … then into me”: the apprehending of their “look,” their “shared expression,” and their “resolve” calls to mind John Berger’s acclaimed essay “The Fayum Portraits,” which asks why the earliest known portraits—found in Egyptian mummy cases from the late first century BCE and the early first century CE—possess such uncanny vitality, feel so immediate, why they “touch us, as if they had been painted last month … as if they have just tentatively stepped toward us.” Berger explains that the making of the portraits, which were not meant for the living but for the Beyond, involved a very particular relationship between the sitter and the painter, who

collaborated in a preparation for death, a preparation which would ensure survival. To paint was to name, and to be named was a guarantee of this continuity.

In other words, the Fayum painter was summoned not to make a portrait, as we have come to understand the term, but to register his client, a man or woman, looking at him. It was the painter rather than the “model” who submitted to being looked at … the Fayum painter … submitted to the look of the sitter, for whom he was Death’s painter, or, perhaps more precisely, Eternity’s painter.

The marvel of Claudia Emerson’s Impossible Bottle is that the highly charged, collaborative perspectives of sitter and artist in this final encounter are made available to the reader simultaneously, indivisibly, as one: The artist, Eternity’s painter—or namer—submitting to the look of the sitter, is, in this case, also the sitter looking. We’re allowed a rare vision inward and outward at once—

I am not this, not here, this time. I am

what I mistook for a shadow

in our walled garden, gathered beneath the concrete

bench, concrete also the sky,

like the cold, sorrowful bottom of something; it is

a collared shadow, though—a stray cat

I see us feeding in the afternoon. And I

will watch it eat from a dish

on the back stoop, then bathe in the open doorway

of the garage, in that narrow shaft

of afternoon light, where I will be also,

and also behind it, where I am

the body of light that swings from the rafters.

[“Infusion Suite, 5”]

What’s offered in these poems, if the reader is also willing to submit, is the opportunity to participate in an exacting and intimate vision of mortality, whose periphery glimmers, suggesting you too will find yourself becoming something else

there

there you are