On any given day in artist Lauren Bon’s Metabolic Studio, a cavernous warehouse on the edge of Chinatown in downtown Los Angeles, you’re as likely to run into a water-rights attorney, a well-connected political fixer, a staffer from a city agency, an engineer, a fabricator, or even a brewer, as you are the artist, who is somewhere in the building, or on her way, or just as likely out in the field far away.

On any given day in artist Lauren Bon’s Metabolic Studio, a cavernous warehouse on the edge of Chinatown in downtown Los Angeles, you’re as likely to run into a water-rights attorney, a well-connected political fixer, a staffer from a city agency, an engineer, a fabricator, or even a brewer, as you are the artist, who is somewhere in the building, or on her way, or just as likely out in the field far away.

But on a recent day this spring, there she was, with a bemused smile, under a mane of wild strawberry-blond hair, standing with a half-dozen members of her studio and a few visitors by a high table tasting beer made from water from the Los Angeles River, which runs a stone’s throw away, behind the warehouse, across the railroad tracks, in a concrete strait jacket. One of the beers was made from filtered water, the other not.

“Which one do you like best?”

It’s a kind of dare, isn’t it?

A small dare for a visitor in the midst of a very big one along the river, for the artist and the city where she has made herself a transformative figure. This artisanal river-water beer might literally work some small chemical or biological transformation in my body. But the communion with a larger vision seems worth the risk. And the beer is not half bad, a nice ale with well-balanced malt and hops, and mysterious but intriguing earthy undertones.

We lift our glasses to the river that has been for a very long time not a river, the river that is reenchanting Los Angeles, the river that will soon power an enormous waterwheel, which will turn right here where we are standing, destroying the studio where it is being conceived, pulling water from the river for the first time in more than a century, and distributing it around the city. Drawings, schematics, and models of La Noria, as Bon calls it, are pinned to the walls, lying on tables, and scattered around the warehouse.

Like its Spanish name, the waterwheel hearkens back to an old Los Angeles, if not the first Los Angeles, before the pueblo even got its name, when this was Tongva territory, then to the very early Los Angeles, where more than a dozen waterwheels lined the river, raising water into the zanja madre—the mother ditch—which carried water to a network of ditches supplying vineyards, groves, fields, and homes. The waterwheels connected Los Angeles to its source.

In the early twentieth century, a booming Los Angeles was separated from the river in three decisive steps. First, an aqueduct was built more than 200 miles north to bring water to the city from the Sierra Nevada—a move mythologized in the movie Chinatown. Then, the city took control of all water rights on the river. Finally, the river was encased in concrete after rampaging floods in the 1930s; it became a drainage ditch, shunting water as quickly and efficiently as possible to the ocean.

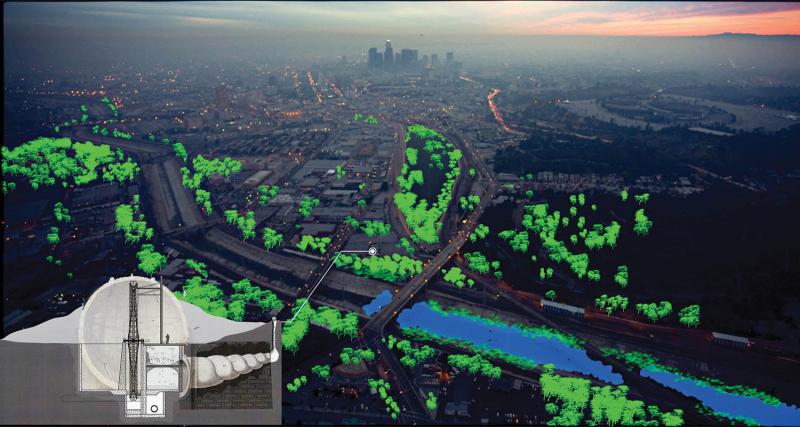

Now Bon wants to “bend the river back into the city” with La Noria, a grand piece of art that she sometimes calls “a device of wonder” and at other times “avant-garde nostalgia.” In the process, she has shaped her artistic practice to shake the foundation of L.A.’s relationship with the river and water by demystifying the Los Angeles Aqueduct, acquiring the first individual water right on the river in more than a century, and soon, penetrating the river’s concrete channel to reestablish a connection between the city and its source.

Lauren Bon was born to a prominent East Coast family but grew up out west. At seventeen, she set out on an unfettered course of her own making that took her around the world, as she got herself educated in art, activism, and architecture in the Middle East, Asia, and Europe before coming back to Los Angeles, where she has undertaken some of the boldest art projects ever in California.

“Artists need to create at the same scale that society has the capacity to destroy,” proclaims a red neon sign on one of the cinder-block walls inside Metabolic Studio.

That sets a very high bar for art anywhere and particularly in Los Angeles, California, and the American West, the vast canvas for Lauren Bon’s artistic practice, where landscapes have been thoroughly reengineered over the past century and more, creating strange hybrids of the natural and cultural, eminently amenable to artistic interventions, to be sure, but demanding a certain scale of imagination and execution.

I asked Bon if the neon proclamation came from her. It has certainly guided her work. But it came from artists Kit Galloway and Sherrie Rabinowitz, who created the Electronic Café International, a global cyberarts network based in L.A. in the 1980s. “Now we call that the Metabolic manifesto via the Electronic Café manifesto, which is also cool because it’s West Coast thinking,” Bon said. “There’s something about these vast expanses that cause you to think differently,” she added. “You think about these big things,” she said. “This mandate to operate on a scale that society is destroying is where that comes from.”

This mandate has forced Bon to grapple with some of the biggest institutions in L.A. and the state—the City of Los Angeles, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, the California Department of Water Resources, the Veterans Administration (one of the largest landowners in the city), and California State Parks, to name just a few. Working at this scale has shaped her artistic practices, and those experiences have also shaped her approach to philanthropy—Bon is a trustee of the Annenberg Foundation, a family foundation established by her grandfather, media magnate Walter Annenberg, and a major player in Southern California. And she has taken the unusual step of investing her foundation trusteeship in the same collective as her artistic practice—Metabolic Studio and its crew of artists, builders, musicians, writers, activists, and organizers. Together they review and decide on all of the proposals that come to Metabolic Studio, Bon’s signature project as a trustee of the Annenberg Foundation.

“So they are the philanthropists,” she said as the hive that is the studio buzzed around her. “And I no longer function as a unique philanthropist in this city. I pass that on to the community that I work with. And we call it ‘citizen philanthropy’ because the eighteen people who work here are not trained to do that job any more than I was. They are just living their lives. And they found themselves in this position.”

Bon found herself in this position in 2001 when she returned home to Los Angeles from Europe, where she had spent a decade consciously exploring and experimenting as an artist, without worrying about exhibiting. She apprenticed with sculptors Michael Singer and Magdalena Abakanowicz, and Beckett set designer Jocelyn Herbert, started the Hereford Salon in her London home, and launched her first large-scale public piece in Belfast, Northern Ireland.

Across the street from the studio, a state historic park is now being carved out of an abandoned rail yard. It is here that Bon created her first big work in Los Angeles. She called it Not A Cornfield.

The thirty-two-acre contaminated site had been acquired by the state, but the effort to clean it up and create a park there was going nowhere. It was still, literally, a brownfield. Bon went to the director of state parks and got permission to plant it with corn. She brought in topsoil and laid miles of irrigation hose. Soon, in full view of downtown L.A.’s skyscrapers, corn was sprouting.

A deceptively simple Magritte-like move linguistically—“Ceci n’est pas une pipe”—coupled with a simple but deeply powerful neo-pastoral aesthetic, a colorfield of green in the heart of postindustrial Los Angeles, Not A Cornfield became an object to think with, a signal and a symbol of a complex transformation in the city’s sense of itself.

“The moment when the old train yard became emerald green with corn, things shifted,” Bon said. “That was a big, big shift. And I could see the power of both the metaphor of corn and the reality of how life brings life, whether it’s ladybugs or hummingbirds or crickets at night. The power of living things in juxtaposition with a place like this gave birth to the notion of a practice that we would call a metabolic structure.”

Not A Cornfield was not land art either, Bon insists, “because we weren’t going to have a cornfield there forever. It was both a cornfield and not a cornfield,” she said. “It was a way of creating the potential for something else to occur there because the site had stalled in its process of becoming. And the cornfield was meant to galvanize it into that possibility again.” It’s not quite sculpture, either, though, she added, which “is often about its formal end being the subject of the work rather than consuming even its formal end into a greater notion of transformation.”

Not A Cornfield was not a lot of things, it turned out. And one of the other things that Not A Cornfield was not, Bon insists, was public art—work that gets commissioned by an agency that acts as an intermediary between the artist and the site. This was Bon’s idea. She brought it to California State Parks. They gave her a green light.

Not A Cornfield was not a lot of things, it turned out. And one of the other things that Not A Cornfield was not, Bon insists, was public art—work that gets commissioned by an agency that acts as an intermediary between the artist and the site. This was Bon’s idea. She brought it to California State Parks. They gave her a green light.

Not everyone was pleased by this artistic intervention in a site fraught with historical tensions. Environmental-justice groups, which had been key in stopping large-scale industrial redevelopment projects on the site, and which had their own visions for the park, angrily rallied against Not A Cornfield with signs reading: Cornfields No, Parques Si. Planta Maiz en tu yarda. No en nuestras. (Plant corn in your yard. Not ours.) La Vanidad No Es Arte. (Vanity is not art.) And, Respecto.

“I didn’t know the hornet’s nest that I was walking into,” Bon said. “I had recently moved to Los Angeles. I felt that this would be a good idea.” She added: “Now, in retrospect, I understand it much more.”

As the corn grew, so did conversations that schooled Bon in the troubled history of displaced and disenfranchised communities in downtown L.A., Chinatown, and Chavez Ravine, where Dodger Stadium now sits atop a ridge above the park and Metabolic Studio; the older history of the Tongva and Gabrieleno; and archaeological remains thousands of years old on the park site, and along the river, from indigenous people whose descendants “still live and practice their ways in these hills around where we live,” Bon said. These were conversations that would not have happened without the “device of wonder” that was Not A Cornfield, she said.

The cornfield came and went in one growing season in 2005, a growing season filled with public events and discussions. And Bon stayed. “I think people were concerned that I came in to take something away, rather than to offer a transformative potential that I would then stay and support,” she said. “And I think over the ten years, I’ve shown who I am around here.”

Out of the cornfield, which was no longer a cornfield, grew FarmLab, a collective of around forty-two people who worked to generate and support projects throughout the city that had “earth, seed, water, and process” at their cores, what Bon calls “metabolic” projects, “taking land that can no longer support life and returning it to supporting life and supporting different strategies of inquiry into how to do it.” And out of FarmLab grew the Metabolic Studio.

And then Metabolic Studio landed in the middle of an epic fight with the Veterans Administration, one of the largest landowners in Los Angeles, thanks to an enormous property on the west side of the city, which was donated to the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, a precursor to the VA, in 1888.

And it was there that Bon’s particular blend of art practice and project-based philanthropy was further forged against a fairly formidable foe. Strawberry Flag started out as a pretty straightforward art-and-service project for homeless veterans. The studio got permission to grow a hydroponic strawberry field in the form of an American flag on the grounds. They discovered art supplies in a room in one of the thirteen unused buildings on the site and began offering an open studio at the site for veterans to write, make art, and talk. They began publishing a monthly broadsheet newspaper, the Strawberry Gazette, filled with stories from the homeless and disabled veterans who came into the studio, along with recipes, horoscopes, and interviews. It read like a small-town western newspaper with a crusading editorial point of view, and a surprisingly intellectual and oddly artistic sensibility.

Then the VA shut them down. The project was demonstrating on the ground a compelling argument for using the site for homeless veterans, in line with its original intention. But the VA has long had other ideas for its valuable real estate. Much of the property has been leased out to commercial ventures and nonprofit organizations over the years, many of which had nothing to do with veterans. Along the way, Metabolic Studio developed a case for a breach of trust, based on the original deed of the land for veterans, but Bon didn’t want to sue the Veterans Administration. She saw the studio’s role as a catalyst for bringing other resources to the fray. The ACLU took up the case. And earlier this year it reached a settlement with the VA to rededicate the site to veteran housing.

Like many of Metabolic Studio’s projects, this one had a life as a work of art; it was exhibited at LACMA. But the scale of the transformation underway at the Veterans Administration site is much larger than even the art can convey, and its full effect may not be known for many years.

Meanwhile Bon had her sights set on an even larger horizon—what she came to call “the delta of Mount Whitney.”

“Every river has its delta,” Bon said as we sat beside the railroad tracks and the Los Angeles River in back of Metabolic Studio, “the place where it deposits its load before it dissipates.” By taking water out of the river here, Bon wants to create a new imaginative delta, where the wastewater that normally runs out to the Pacific Ocean will go back into the city, modeling a new way for L.A. to imagine managing its water more sustainably.

The delta of Mount Whitney pays tribute to the highest mountain in California, and indeed, in the lower forty-eight. At 14,505 feet, Mount Whitney towers over the Owens Valley, one source of the city’s water, 240 miles north in the Sierra Nevada. The Los Angeles Aqueduct was both signal achievement and original sin for Los Angeles.

The Owens Valley became “a sacrificial twin of the city,” Bon said. “The more I understand Los Angeles, the more I realize that it kind of had a symbiotic birth,” she said. “One has thrived at the expense of the other.”

Los Angeles didn’t just get water from the Owens Valley, water that made the modern metropolis possible. It also got silver, which was transformed into film by George Eastman in Rochester, New York, and shipped back to Hollywood, for the city’s booming iconic industry.

The Metabolic Studio has made these two elements, silver and water, the centerpiece of a project Bon calls AgH2O, a long and deep engagement with the Owens Valley, meant to acknowledge the debt, pay respect, and build relationships. The work that has emerged has varied from the artistic (photographs made using silver taken from the tailings of an abandoned mine in the mountains above the valley) to the environmental (using manure from the mule trains that carry packers into the High Sierra to build up soil for community gardens in the valley) to the social and cultural (opening an IOU theater in the valley for movies and a radio-theater company) and performance (a 100-mule train led by Bon traced the entire length of the aqueduct on its 100th anniversary).

“Part of AgH20 is the consciousness of the acknowledgement, saying, ‘We do owe you,’” said Bon.

Here, again, Metabolic Studio has practiced project-based philanthropy, in this case in a community that has had few philanthropic resources to create projects—the gardens, the theater—and attract attention and more support for the community, in a way that is virtually inseparable from its artistic practice. Although there is a clear spectrum—the studio’s photographic prints have been exhibited and are sold in galleries, clearly establishing and holding down the “art” end of the spectrum—in the day-to-day hubbub of the studio, and in conversation with Bon, it’s nearly impossible to tell for sure where art ends and philanthropy begins or vice versa.

In all of this work, so far, Metabolic Studio has studiously avoided leaving physical objects of art behind. All of the artwork has been ephemeral. It has been about using the labor of art—art work—to work a transformation. The waterwheel, which will transform the studio, is the first piece that will be permanent.

Still, “everything is about catalyzing other things to happen,” Bon said. “In proposing a device of wonder—a waterwheel and a dam and a new distribution system— I’ve been able to catalyze a change that needs to happen. And it’s happening because it needs to happen, not because I’m a great artist.

“But maybe I’m a good enough artist to get that ball rolling,” she said. “And I’m happy with that, you know?”