Budd Schulberg was born into Hollywood royalty in 1914.

The city—and the movie industry—hadn’t existed for very long at that point. And his father had helped to build what even then existed, out there in the desert, relatively near the Pacific Ocean. His father, the estimable B. P. Schulberg, was a movie-producing power-house. He’d introduced America to Clara Bow—the original “It Girl”—as well as the character that became the American version of Sherlock Holmes: Nero Wolfe. He made a lot of movies, and helped to touch off “the industry,” which has since gained a bit of worldwide cultural traction.

Budd Schulberg himself was a smart kid who grew up to become both a Hollywood legend and a classic cautionary tale of Tinseltown. He went to school in California, graduated from Deerfield Academy, Massachusetts, then attended Dartmouth College for his higher education. As a young man, just out of school, he was embracing The Red and the Black as well as Man’s Fate and many other Communist-inflected books, and he hoped to use film-making to make the world a more fair and equitable place. At the time, in his mind, socialism figured into that formula, to a degree.

Still, Schulberg started small. Looking to go into the family business, he wrote a screen treatment titled Winter Carnival. It was, to say the least, a lightweight story, involving a festival that happens every winter at Dartmouth.

The treatment was picked up and green-lighted, and suddenly young Budd Schulberg—still in his twenties—was off to the races. The movie’s producers wanted a little “adult supervision” on the script, so they asked a washed-up novelist turned screenwriter—a man named F. Scott Fitzgerald—to be his partner on the script.

Fitzgerald was one of Budd Schulberg’s literary heroes. The convergence was too much to ask for. It would also turn out to be simply too much. On the flight from Burbank to New York, Schulberg’s father had given them two bottles of champagne to celebrate with while on the long journey eastward. After all: It was a great thing, this journey!

The plan was simple. After a night spent in New York following the long airplane flight, they were to take a train up to Dartmouth in Hanover, New Hampshire, to do some on-the-ground research in preparation for actual screenwriting. The champagne slid Fitzgerald into an alcoholic bender, and he disappeared into New York for several hours. Ultimately, they caught a train north, and while the movie was made (you’ll find it sometimes on tv), both of its original writers were fired by the producers for “doing research” at Dartmouth. They were fired mostly because one member of the team was beyond reasonable functioning—due to “personal problems.”

Hey: welcome to Hollywood.

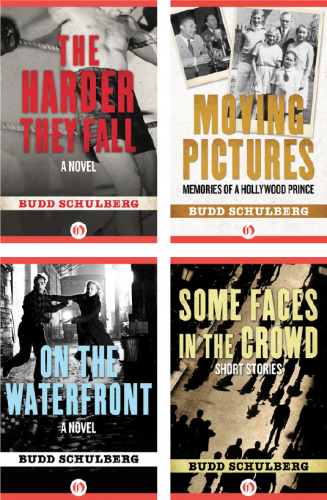

His actual name was Seymour Wilson Schulberg, but everyone called him Budd. Most of his books have been republished over the past year as ebooks in a roll-out from Open Road Integrated Media. His most famous work, What Makes Sammy Run?, is available from Random House Digital. Despite his demise in 2009, Schulberg may soon become something like a “hot” commodity again. Which is wonderful—and deserved.

Shortly after his education (including the “disaster trip” to New Hampshire with Fitzgerald … which was part of his education), Budd Schulberg was drafted to become part of the American forces in World War II. He made promotional films for the United States with the famed director John Ford, among other jobs. But by then, in 1941, he’d already written his first novel, What Makes Sammy Run?

The question mark in the above book’s title remains important. And by now the novel is a classic Hollywood story. It involves a newspaper copyboy from the Lower East Side of New York who has a fascination with good shoes and improving his status. His name is Sammy Glick. And in the first paragraph of the book, he is described as “a little ferret of a kid, sharp and quick. Sammy Glick. Used to run copy for me. Always ran. Always looked thirsty.”

Through the book’s story arc, Sammy rises—using guile and energy, intelligence, and a compete lack of ethics—to become one of the most prominent producers in Hollywood. Still, Sammy Glick is plagued by insecurity and a need for shined and good-looking shoes. For Sammy, it doesn’t end all that well.

The book became a sensation. It was an enormous bestseller, exposing Hollywood’s underbelly.

With his Army stint and the OSS job he held and VE Day afterward, he came home and went back to work. Budd Schulberg wrote books and screenplays, and was the chief boxing writer for Sports Illustrated, and these three aspects of his life often overlapped.

His books include Some Faces in the Crowd (1941), a collection of short stories, some of which were previously published in prominent American magazines. One story was about an Arkansas drifter who, due to the protagonist’s intelligence and good luck, ends up as a national political figure before his public self-destruction. It was very lightly based on the political philosopher and comic Will Rogers. It tells the story of how one man’s personality, smash-and-grab life, and philosophy turn him into a national icon—and then goes horribly wrong by his own misdoings. (Is there a leitmotif growing here?)

Then Schulberg wrote a fantastic novel about his failed trip to make Winter Carnival with Fitzgerald, titled The Disenchanted. Today it may be ranked as one of the least-read Holly-wood classic novels. As a reader, you can have The Day of the Locust. Nathanael West is no Budd Schulberg. Schulberg’s work blows it into the trees.

Consider bits of the jazz-like opening of The Disenchanted, Chapter 10:

The white tile of the Holland Tunnel rolled past them as the airline’s black limousine raced through the enormous artery feeding the heart of the city.

Finally they burst out into the open, into the swarming labyrinth of downtown Manhattan. There were the trucks, the cops, the bars, the stores, the cabs, the reckless pedestrians picking holes through traffic like shabby Albie Booths. There were fruit, all colors, vegetables, hock shops, Italians, Jews and the global hustle of the water front… . It was all here now, the money and the power and the brains they employ and their great army of camp followers catching the crumbs … punch-in punch-out, spiced-ham sandwich and a cupa coffee.

The man could write one hell of a paragraph.

Schulberg also wrote perhaps the best prize fighting book of all time: an on-the-ropes tight novel titled The Harder They Fall (1947), which later became a movie starring Humphrey Bogart. The book involves such issues as maintaining a sense of unbreakably strong personal discipline, the notion of honor, the terrifying beauty of combat, and, ultimately, death. As fictionalized stories go, book subjects can’t get a whole lot larger.

During that time, he also “script-doctored” a number of films, and wrote a little black-and-white movie that premiered in 1954 and was titled On the Waterfront. To get it set into motion, Schulberg barged into producer Sam Spiegel’s room at the Beverly Hills Hotel, woke him up, and secured financing. Of course, the film also had a secret weapon: a young actor named Marlon Brando, who, once he was hired, actually went and worked as a stevedore in order to prepare for the role. On the Waterfront was directed by the legendary Elia Kazan, for which he won an Academy Award.

After that, Schulberg and Kazan worked together again on another film based on Schulberg’s work: A Face in the Crowd (1957), which came from one of the pieces in his book of short stories by a similar title. The star of that particular movie was a mentally tough but agreeable guy from North Carolina. He was a newcomer to the film business. That actor’s name was Andy Griffith. That role made his career.

Hey: that’s Hollywood.

In Richard Schickel’s biography of Kazan, the author writes, “A Face in the Crowd is a major film that most people mistook at the time as a minor—or at least noncontroversial—one.” It has since become a classic of escalating public power gone bad. Again: there might have been a larger metaphor beyond that.

Budd Schulberg had it going on.

By then, however, Joseph McCarthy and his House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) had come along and derailed Budd Schulberg’s career. Back in 1951, and during a moment of either weakness or deep personal honesty, Schulberg—having been called before the Committee in Washington—“named names” of other prominent Communist-minded people in Hollywood. After that, despite some film projects already planned and moving along, much of his career was ended. Despite his obvious intelligence, “ability with a story,” and pedigree, he became a Hollywood outcast. On many levels, Hollywood is a very small town, and once you alienate the prominent villagers through “naming names” to a government council gunning for people to blame in their quest for political capital, it’s hard to regain your local townspeople’s trust.

With regard to Budd Schulberg, Hollywood just walked away.

After living in Los Angeles, and later on a farm in southeast Pennsylvania, Budd Schulberg finally moved to a place in Quiogue, New York, and all but disappeared from public view. He’d made his money and had written an Oscar-winning movie and several best-selling books. Of his later books, Everything that Moves is pretty good. Sometimes, in the afternoon, he’d have a highball which his last wife, Betsy, would give him a hard time about. (His previous wife, the actress Geraldine Brooks, had passed away.)

Then, the most remarkable thing happened. In the last decade of his life, Budd Schulberg—as a public thinker and public figure—made a resurgence. In the years before his death, he began writing regularly, and there was a revival of the What Makes Sammy Run? musical headed for Broadway and possibly for a movie production. In Vanity Fair, he wrote of Marlon Brando and of Hollywood history. His output of words remained prodigious and just insider-y enough that only a Hollywood native knows the things he was talking about. The magazine stories were also characteristically Budd Schulberg: jaunty and bebop jazzy in tone. He was well into his nineties, but he was clearly enjoying himself at a typewriter keyboard again.

It was beautiful to witness.

He was writing virtually right up until he died, in 2009. In screenwriting terms—and terms “of story”—he’d done it all. As he’d put it, “you know how the story goes”: an easy opening, followed by the early and embarrassing stumble, and then comes a rise to fame; succeeded by some public ignomy and professional exile, and finally that all-important comeback.

Budd Schulberg turned out to live perhaps the original Hollywood life. As they say out there, among producers at a long table in some room in Hollywood or Malibu: “That’s good story. We should put it on camera.”

Budd Schulberg, in his life, had “a good story” if ever there was one.