The story of Snow White—most familiar to Western readers in its Brothers Grimm literary incarnation from the nineteenth century—is often conflated with that of Sleeping Beauty, known to readers primarily through translations of its artful literary version, from the seventeenth century, by Charles Perrault. Both young girls are put into a suspended sleep, and each is awoken to find, hovering above her, a handsome prince, who takes her off to Happily Ever After. Underneath these stories is the theme of resurrection and eternal life in Paradise; for most European and many American households of past centuries, thoughts of the New Testament would not be far away.

Contemporary feminist historians and commentators of the fairytale point out that the Grimm brothers’ 1812 first edition has not a stepmother, but rather Snow White’s biological mother, setting out to have her murdered because of envy over her beauty. With either version, Snow White’s miraculous restoration to life after she has bitten into the poisoned apple would have extended the attraction of the tale to all Christian believers, boys as well as girls, adults as well as children: The story of Adam and Eve’s transgression in Eden and the remediation of it through the torment and resurrection of Christ have been compressed into the story of one character, without announcing themselves. The biblical resonances wouldn’t have needed to be spelled out for a culture where, if a household only owned one book, it would be the Bible.

As popular as bound volumes of Grimm and Perrault once were, the vehicles that have most widely disseminated their stories are the animated, feature-length musical films produced by Disney over most of the past century. And most highly esteemed among them is Disney’s first: the 1937, eighty-three-minute Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs—the most successful, influential, and meticulously collaborative of them all—which is celebrating its seventy-fifth birthday this year. (Indeed, concepts and realized scenes cut from Snow White were used in subsequent Disney features at least throughthe 1959 Sleeping Beauty.) Prior to home-media technology that can summon up a film 24/7, the studio was quite careful to time the theatrical re-releases of Snow White in order to tap into new generations of young filmgoers. Even with the rise of home theaters, one’s experience of the film on a big screen is something quite special. It is more than a triumph of craft and technology: It is art.

This past September, in a nod to the importance of animation as part of the history of cinema, the New York Film Festival screened Disney’s animated masterpiece during the festival’s fiftieth-anniversary celebrations. However, the context for the film’s appearance demonstrated some misunderstanding of who—at least among cinephiles in New York—cares about the distinction between watching the picture at home as opposed to falling into its glories in a movie theater. In the case of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, there is an even further distinction—that between actual film prints, which served as the basis for VHS and DVD versions prior to 2004, and a brighter, sharper, High Definition digital incarnation that was created for the 2009 Blu-ray release.

When I asked about the HD version shown at the festival, Theodore E. Gluck, director of library restoration and preservation at the Walt Disney Studios, explained that the camera-original nitrate negative was scanned at 4K resolution, then further restoration was done:

All of the clean-up work was carried out at a higher-than-HD resolution, and a great deal of effort went into the dirt clean-up and establishing the “look” of the film. The Restoration Team reviewed reels from a surviving Technicolor print held by the Motion Picture Academy, as well as examined surviving cels and other materials at the Studio’s Animation Research Library. The original opening title sequence, which had been removed/re-photographed in the early 1950s for “Buena Vista” re-releases, was found and reconstructed back into this restoration.

The difference between watching the Blu-ray Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs at home, even in luxurious circumstances, and watching it at the Film Society’s Walter Reade Theater is more than in the size of the projected picture. It is the collective energy of a live audience. But it paled in comparison to the original screening.

When Disney’s Snow White was given its theatrical première, at the Carthay Circle Theatre, in Los Angeles, on December 21, 1937, the capacity house of 1,500 seats was filled by the likes of Claudette Colbert, Marlene Dietrich, Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., Ernst Lubitsch, George Cukor, and Charlie Chaplin. Disney at that time was considered by prestigious cultural critics to be turning out, by way of cartoons, some of the most avant-garde art in America and, with it, to be suggesting a future for filmmaking in general. To be present at the public opening of this first feature-length version was a big deal. The voices of Snow White and the Prince, Adriana Caselotti and Harry Stockwell, were present, along with a full orchestra, to perform songs from the picture. The body of Snow White—young teenager Marjorie Belcher, who, after serving as a live-action reference for Disney characters, would go on to stage and screen immortality as dancer and actress Marge Champion—was also present, but exiled to the balcony. Unlike Caselotti, who was prominently showcased by the Disney publicity department, Belcher was kept under wraps; her participation was a secret from the public. She had been rotoscoped by the Disney team, a procedure in which films were made of her executing every movement and gesture of Snow White’s character, including the lip-synching of Snow White singing; then the films were traced and elaborately reworked by Disney artists, so that only her physical motions were represented in the finished product.

In 2012, no one cares that rotoscoping was used in the preparation of the movie; however, in 1937, when Disney was pursuing animation as a work of art that recreated the breath of life through pencil, paper, ink, paint, lighting, and cinematography, the possibility that audiences might write off this complex technique as “merely tracing” made it imperative to hide the dancers who served as the live-action references for Disney characters. Belcher, in fact, didn’t even know that she had been rotoscoped—only that she had been filmed—until many decades later, when she encountered a Disney exhibit that explained the rotoscoping of her films and then the artistry of the Disney animators who used them as a basis for creating figures from the imagination.

Marge Champion—whose oral histories about her Disney experience have been cited in books by Disney historian John Canemaker and others, as well as by me, and also have been recorded by the New York Public Library—spoke to a class that I teach on “Dance in Film” about sitting in the Carthay balcony and looking down on the glitterati of Hollywood in amusement, as she knew something most of them did not. The only child present (“child” in terms of chronological age) that night seems to have been the biggest movie star of the Great Depression, Shirley Temple, who posed with seven “little-people” adult actors, costumed as the Dwarfs.

Seventy-five years later, the New York Film Festival’s Snow White screening took place on a Saturday, at 10 a.m. It was billed as a “family” event. In terms of marketing, that would seem sensible from one perspective: Snow White is now considered one of the “Disney Princesses,” whose embodiments as dolls and figurines, and whose dress-up costumes, have successfully appealed to preadolescent girls (and to some of their mothers as well). However, there is a separate audience for animated films, especially historic ones. It is a fully grownup audience—mostly male, though with increasing numbers of female members, too—comprising animation fans, aspiring animators and historians, and movie buffs. This audience does not, like the family audience, plunge into the fantasy of a picture; instead, it analyzes the storytelling techniques, imagery, sound, and effects according to both period and contemporary standards of moviemaking, animation development, and design. And, at the Walter Reade, this is the audience who mostly filled the theater’s 268 seats. When it came to children under three feet tall, or in arms, I counted four.

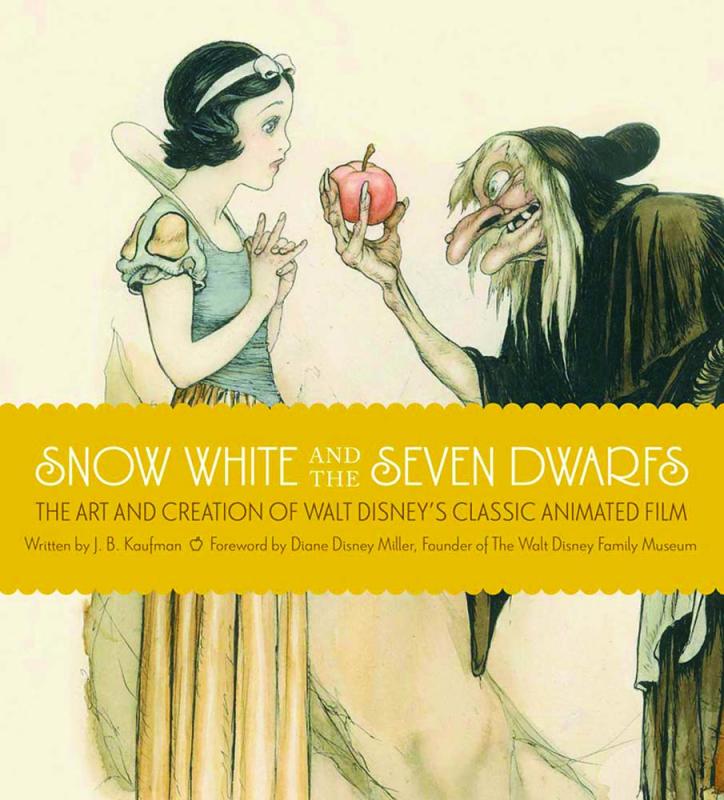

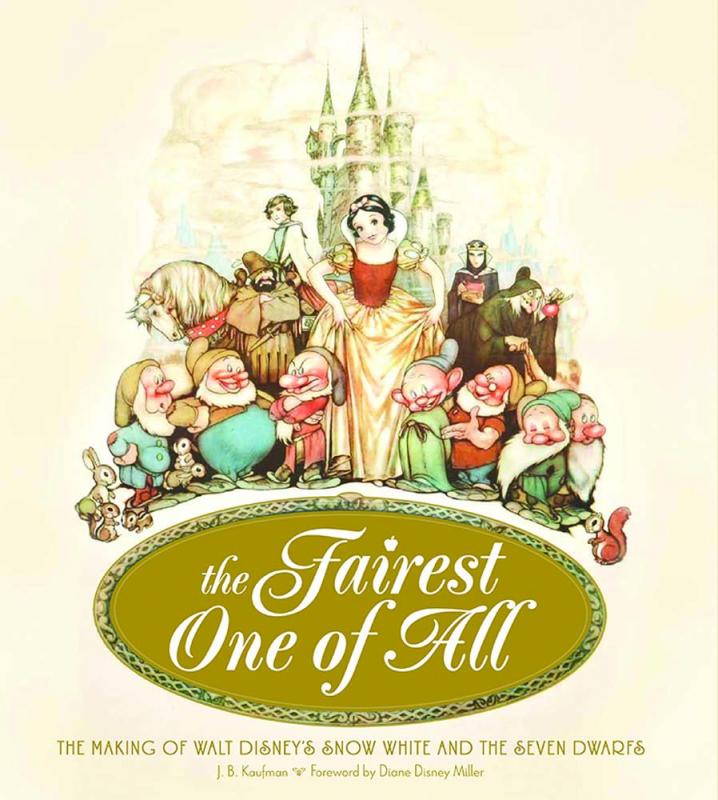

Certainly, it would be a rare child who would pore over the meticulously researched texts in J. B. Kaufman’s two new, lavishly illustrated coffee-table volumes on the making and legacy of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Both books were being raffled in the Walter Reade lobby, and there was a long line to examine the sample copies: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs: The Art and Creation of Walt Disney’s Classic Animated Film is a catalogue of an exhibit at The Walt Disney Family Museum, in San Francisco, on the occasion of the film’s seventy-fifth anniversary. Kaufman’s larger, much more comprehensive study, The Fairest One of All: The Making of Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, is a history of the film’s conception, cultural context, and, in detail, its realization. The latter book contains exhaustive information on the story conferences, color, music, and actual animation of the film. It explains that several animators were assigned to create the character of Snow White—in long shot, in close up—and it painstakingly distinguishes between, for instance, the sophistication of Ham Luske’s exquisite representation of Snow White as a young adolescent and Grim Natwick’s somewhat more matured representation of her, both so carefully blended into the final film that, without Kaufman’s cel-by-cel guidance, it’s almost impossible to be aware of the difference. Readers will learn about the picture’s funding (Walt Disney and his brother, Roy, essentially risked the company on the project, called “Walt’s Folly” in some quarters), the circumstances of its initial screenings, and its legacy for other Disney animated films. One could hardly ask for a more considerate history of a single moving picture—and can hardly imagine a less engaging text for little children!

Kaufman, a meticulous researcher on animation and the Disney studio as a business, summarizes some of the historiography of the fairytale and, wonderfully, the nineteenth- and twentieth-century theatrical and cinematic antecedents of Disney’s film, including the 1916 Snow White silent, from Famous Players (later Paramount), with Marguerite Clark as the title character, which entranced Walt Disney as a boy. Marjorie Belcher’s participation as a live-action reference performer for Disney is encapsulated and illustrated with frames from her filming, though not explored; for more about her (or the young ballet student, Louis High-tower, the live-action reference for the Prince), one must consult other sources. However, Kaufman makes a fascinating point about the development of Snow White as an onscreen presence with respect to the character’s age. He points out that, at the start of the Grimm story, Snow White is seven years old; yet, by the end of the story, she’s old enough to marry the Prince. Referring to a predilection for the “child/woman in popular entertainment” in America at the time Walt Disney himself was growing up, Kaufman writes:

For viewers of the 1930s as for us today, those inherent contradictions [of the girl/woman] are encapsulated in the Disney Snow White. The baby voice singing songs of mature romantic longing, the tension between the Luske little girl and the Natwick young woman, combine to give this Snow White a complexity that reflects both the aspects of her traditional character. It’s a quality missing from later fairy-tale figures like the Disney Cinderella, who is unmistakably a young woman throughout her story, and therefore a far less interesting character. Somehow, on the screen, Snow White is made to contain both the disparate poles of her heritage, and they coalesce into a vibrant and compelling girl/woman—the sum of her literary antecedents, with the added dimension of a new and distinctly twentieth-century art.

Kaufman’s case for Disney’s first feature-length animated film as “the fairest” in both the Disney canon and in comparison with other animated features is strongly argued, simply through his account of the movie’s making. And one admires the lengths he goes to call attention to the contributions of individuals among the nearly 1,000 who took part in the Disney studio at the time. However, there is one discussion that makes this reader a little uncomfortable: It concerns a competitor’s version, the 1933, seven-minute, black-and-white cartoon from the New York-based Fleischer Studios, Snow-White, directed (like all the Fleischer cartoons) by Dave Fleischer, with Betty Boop—Fleischer’s diva—in the title role and Cab Calloway in a haunting rendition of “Saint James Infirmary Blues” on the soundtrack. Unlike Disney’s Midwestern concern with realism and what today we might call family values, Fleischer’s cartoons tended to go for irony, the risqué, and one-off gags about physical transformations of the everyday world into surreal forms, giving the effect of fleeting emotions. They are amusing, often charming, sometimes unsettling (when something familiar can, at any moment, become something else, one is in a world that can’t be trusted), even weird, yet their ironic perspective puts actual tragedy at a distance, which gives viewers a comforting moment of respite from real-life miseries. When Betty Boop, having succumbed to the evil queen, is encased in a coffin of transparent ice, one doesn’t for a moment feel mournful, though there is an underground sequence of continual transformation that may seem sadly strange as well as enchanting, owing largely to Calloway’s plaintive song, which accompanies it. However, when Disney’s Snow White lies in her glass coffin, attended by the grieving dwarfs, an audience who hasn’t seen the picture before may actually feel bereft. (Initial audiences for the film wept.) “For devotees of this kind of wildly non-sequitur animation,” Kaufman writes, “the Fleischer Snow White [sic] is a classic in its own right, but it’s related to the Disney Snow White by name only.”

It’s possible that Fleischer was addressing issues important to small children. “Always in the way,” Snow-White sings, “I can never play.” The non-sequiturs are imaginative associations of what “play” is—which doesn’t include grownup romance. Snow-White is rescued by the mirror itself, which transforms the queen into a monster and releases Snow-White to be with her friends, Ko Ko the clown and Bimbo the dog. There is no rescuing prince. The Fleischer Snow-White was the work of a single artist, Roland C. Crandall, one of the few Fleischer animators who refused to abandon the studio for Disney. In 1990, Fleischer’s cartoon was judged by 1,000 animation professionals and students to rank as nineteenth among the fifty greatest animation shorts of less than thirty minutes long. (Disney’s magnificent 1935 Mickey Mouse–Donald Duck short, The Band Concert, in which Newtonian physics is hilariously deconstructed in the course of a tornado, was voted number three.)

In animation, certain rules relating to cause and effect can be transgressed as long as it is made clear and reasonable to the audience that the rules were broken because others replaced them. In Disney’s Snow White, there are numerous such replacements. The forest animals who act in concert with Snow White to help her find lodging at the Dwarfs’ house and to clean it are presented as nurturing creatures (unlike the rodents and insects associated with the Evil Queen), and so their nurturing is extended or translated into human terms. When the Queen wants to present Snow White with the poisoned fruit and needs to disguise herself as an old woman so as to arouse the girl’s sympathy and make her open to accepting the apple, the Queen must first consult a book, titled Disguises, in order to get the recipe for the brew that will change her body and voice.

But earlier in the film is, debatably, the greatest passage of transformation: the scene where Snow White, terrified at almost being stabbed to death by the Huntsman—who, at the last moment, undergoes a change of heart (yet another kind of transformation though not a surreal one) and encourages the girl to flee—runs into the forest, where, as she runs, daytime suddenly becomes night, bony roots and branches seem to acquire lives of their own, and pairs of eyes without faces follow her. The emotion of Snow White’s flight is sparked by her encounter with the Huntsman, whose resolve to carry out the Queen’s orders to murder the girl is embodied in his face. Then, we see the gleaming upraised dagger in his hand; it is held for a moment, then dropped; his emotional conversion takes place offscreen and is indicated by metonymy, the dagger being raised then falling free. The Huntsman’s resolve has turned to mercy. Then we see the Huntsman urging Snow White to run for her life. As Kaufman makes clear, this one moment of drama occasioned hours and hours of story conferences and expensive color testing of possibilities. In the book sometimes informally called the “Bible” of Disney animation—the huge, 1981 how-we-did-it account, Disney Animation: The Illusion of Life, by Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston, two of Disney’s core animators—one finds an explanation of why the animation of the weakening Huntsman works but also why, psychologically, the subsequent scene in the forest brings moviegoers to identify with Snow White as she struggles to overcome her rising terror in the dark wood:

Today, we easily can see the ingredients that made it [the Huntsman’s change of heart] work so well. The crew concentrated on just the essence of the story situation, not letting any part become overdeveloped; they used carefully planned dramatic staging rather than explanatory scenes; and they underplayed the emotional aspects of the acting instead of calling for overwrought, tormented histrionics. As a result, the audiences were swept along, caught in a web of their own imagination, convinced of the intensity that never was actually shown. The less they were told, the more they filled in with their own thoughts; and the less that was said, the more they seemed to understand.

In fact, that idea of audiences “filling in with their own thoughts” is exactly what Walt Disney wanted in the depiction of Snow White’s flight in the forest. Kaufman traces the dark shadows of the episode to German Expressionist art and cinema of the early 1920s, but when one reads the meticulous transcripts of Snow White story conferences, Disney doesn’t speak in those terms. His immediate intuition drives the discussions—his actor-director’s ability to enter action imaginatively and to ask what next? It was Disney’s intuition that the terrors of the forest were not real (wouldn’t be independently confirmable) but rather were projections of Snow White’s state of mind. In this, Disney—perhaps not conscious that he was doing it—was following an ancient literary tradition about the representation of what happens in a forest. As the literary scholar Robert Pogue Harrison wrote in his 1992 cultural study, Forests: The Shadow of Civilization:

[T]he forest appears as a place where the logic of distinction goes astray. Or where our subjective categories are confounded. Or where perceptions become promiscuous with one another, disclosing latent dimensions of time and consciousness. In the forest the inanimate may suddenly become animate, the god turns into a beast, the outlaw stands for justice, Rosalind appears as a boy, the virtuous knight degenerates into a wild man, the straight line forms a circle, the ordinary gives way to the fabulous.

The flight into the forest by Disney’s Snow White is set in this place “where the logic of distinction goes astray,” although the cause for the straying is a mistake in the perceptions of she who flees, not—as in Shakespeare et al.—a confirmable change in external conditions or relationships. To make this distinction legible to moviegoers required another round of hours and hours of story conferences and exhaustive work by inspirational artists and animators. When we the audience members are in the forest with Snow White, we viscerally experience its space and shadows and possibilities as she does, even though they are entirely created through art and technology; and, when it turns out that the yellow eyes belong to cuddly deer and rabbits, and the lurching limbs are merely twigs, we share in her relief, and in a daytime light, as if a parent had flicked on a lamp to drive away a child’s nightmare.

In terms of the challenges for both story construction and animation, the forest passage may not be surpassed within the world of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Indeed, within the conventions that Disney set up, it can stand comparison for its artistry with astounding young-women-in-the-forest scenes from live-action features in world cinema: fearful Belle riding through the forest on her way to the Beast’s castle in Jean Cocteau’s 1946 La Belle et la Bête; or the moment when Ingmar Bergman’s knight and squire, returning, exhausted, from a decade in the Crusades, discover the fourteen-year-old girl Tyan, her head shaved and her hands broken, tied to a ladder in preparation to be burned alive as a witch, in The Seventh Seal (1957); or the sequence of the isolated and vulnerable yet feisty little girl looking for her father, in Benh Zeitlin’s jungly bayou during his remarkable 2012 film, Beasts of the Southern Wild.

There is one set of forest scenes in world cinema that seems to me greater, and it is from a movie that, in nearly every way, is the opposite of Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs: the light-filled, daytime scenes in Akira Kurosawa’s 1950 Rashomon, set in an actual forest, where none of the characters is reliable or trustworthy and where it is impossible to pin down the circumstances, agents, and motivations for the rape and murder that all witnesses (and participants) agree took place. In some of Kurosawa’s forest passages, the experience is close to that of silent film—motion without dialogue, only musical accompaniment (in the most beautiful section, a European bolero for Western acoustic instruments). For the forest scenes, Kurosawa not only broke faith with the idea of offering a character with whom the audience could identify, but he also broke faith with a rule of cinematography: He shot directly into the sun, which becomes a cyclops of Truth, the only eye that saw what actually occurred.

When I rewatched the film recently, I noticed some unnerving correspondences to Disney’s Snow White. At one point, the memorable thief played by Toshiro Mifune looks at a vast skyscape and seems to have a vision of a tiny horse and rider, very similar to a moment at the end of the Disney film, when the prince’s ensemble, leading his horse on which Snow White is seated, is seen suddenly in the context of the entire landscape, tiny figures traveling to the prince’s celestially radiant castle. Another correspondence between the films: The humane mercy of the woodsman of Rashomon—who offers to shelter an abandoned infant in his home with his other children, even though he is poor and the baby will be another mouth to feed—and the mercy of Snow White’s Huntsman who saves her life, even though he has to face the possible consequence of the evil Queen’s wrath. And, perhaps the most literal correspondence: Our first glimpse of the doomed aristocrat leading his elegant wife through the forest on a noble steed is especially magical because the beautiful wife’s kimono, peaked hat, and long veil to protect her from insects are all … snow white.

Did Kurosawa see the Disney film and remember it? He doesn’t mention it in his account of making Rashomon in his memoir, Something Like an Autobiography. Nor does his faithful “script girl,” Teruyo Nogami, mention it in her memoir, translated as Waiting on the Weather: Making Movies with Akira Kurosawa. However, Kurosawa was a painter before he was a moviemaker, and he might have read the manga, the graphic novels so popular in Japan, which were influenced by Western cartoons. And, an avid moviegoer, with a special love for Western cinema, he might at least have seen the animated films from the nascent Japanese animation industry during the 1930s: The largest influences on them, apparently, were the animated films of the Disney studio. And, when Kurosawa created his picture about iconic warriors, the samurai, of course, as with Disney’s dwarfs, there were seven of them. It’s tantalizing to consider that world cinema took a huge turn after World War II, plumbing the instability of the human heart, as Kurosawa might put it, as never before. In this context, the place where Disney’s prince leads Snow White on his horse out of the forest toward hope and love is where Kurosawa’s husband and wife enter it.