Visitors fortunate enough to have seen “The Moon Has No Home” were introduced to a striking new perspective on an art form that has enthralled interested viewers since the 1854 opening of Japan to the West. The show’s very title hints at something different. “The Moon Has No Home” is a line of a poem found on a print, Lady Chiyo, by the 19th-century artist Tsukioka Yoshitoshi. Not all connoisseurs of Japanese prints would consider Yoshitoshi or the period in which he worked important in the history of woodblock prints. Yoshitoshi’s creation of disturbing and lyrical images has led many authorities to consider him a decadent, a figure associated with the decline of Ukiyo-e. Hence the show’s very title tells us that this installation is not just a presentation of prints—it is an interpretation, and a revisionist one at that.

While the exhibition’s title hints obliquely at a revision, the catalogue’s two essays make this aim emphatic. In the first essay, “Bringing Home the Changes: The Implications of New Views of Ukiyo-e on Their American Study,” Sandy Kita, assistant professor of art at the University of Maryland, makes a strong case for rethinking traditional views of Japanese woodblock prints. Kita calls for a reconsideration of basic issues and assumptions such as the definition of Ukiyo, the nature of this art, and the validity of certain prevailing estimations. The term Ukiyo-e translates to “uki,” floating, “yo,” world, “e,” pictures—thus, pictures of the floating world. But what is this world? Richard Lane, author of one of the most authoritative studies of Japanese prints, Images from the Floating World: The Japanese Print (1978), declares that Ukiyo refers to the brothel and theater district of Edo. Its art, by extension, is a representation of the area’s principal inhabitants—actors and courtesans, precisely what most of us envision when we think of Japanese prints. But this, as Kita demonstrates, is a very narrow definition of Ukiyo, one which delimits considerably the subject matter of the prints.

For Lane and other writers who offered the same valuations, such as James A. Michener and John Bester, Ukiyo-e peaks in 1810. With the exception of the two great landscape artists, Hokusai and Hiroshige, both of whom worked after 1810, Lane, Michener, and Bester have little regard for work produced in the 19th century, dismissing it as the “decline of Ukiyo-e.” Such an estimation, argues Kita, overlooks and misunderstands the work of a number of great 19th-century artists, such as Kuniyoshi, Yoshitoshi, Eisen, and Kiyochika. This exhibition and its accompanying catalogue advocate a more fluid interpretation of Ukiyo.

Kita urges us to consider the roots of this tradition in medieval Japan, in which the word Ukiyo—created of two written characters, one of which denotes the world of sorrow, the other, the floating world—had a broader meaning. Our world is sorrowing because we are mortal. In Buddhist terms it is also seen as impermanent and hence floating. Our mortal perceptions are inevitably “flesh-bound.” Notwithstanding the impermanence of our world, Japanese artists often recorded its particulars painstakingly, and what they register is wonderfully varied. While artists depicted abundantly the subjects noted by Lane—actors, courtesans, and landscapes—they also portrayed less tangible subjects, such as dreams, fantastic events, mythical figures, and ghosts. Artists of the Floating World excelled in portraying both reality and fantasy. If we take into consideration this more fluid definition of Ukiyo and the variety of subjects found in Japanese prints made both before and during the 19th century, we arrive at a much more dynamic understanding of its art.

Kita and Steven Margulies, print curator at the University of Virginia Art Museum, have taken great care in their selection and display of the prints. While Kita’s essay seeks to broaden our understanding of the term Ukiyo, the exhibition has somewhat different ambitions. The show is divided into four sections: “Introducing Ukiyo-e: Quality, Connoisseurship, and General Features,” “Military, Court, and Legendary Themes,” “Subverting Authority: Repetition, Deconstruction and Combinations of Words and Images,” and “Yoshitoshi Group.” Even a cursory look at these titles suggests a wide range of concerns. This exhibition has two objectives—one pedagogical, the other critical. The first two sections aim to educate viewers, to introduce us to some points of connoisseurship and to themes often found in woodblock prints. The last two sections complement Kita’s essay: they seek to stimulate a greater appreciation of 19th-century artists and of Yoshitoshi in particular.

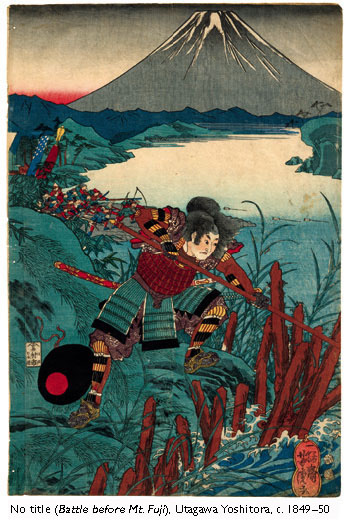

The prints in the first section fulfill the curators’ desire to educate the viewer’s eye beautifully. A number of works—Utagawa Yoshitora’s untitled work, provisionally named Battle before Mt. Fuji, Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s triptych, Edo Murasaki, and Utagawa Kunisada’s Kasugaya Tokijino and Hamanaya Urasato—furnish outstanding examples of the technical excellence of the printer. As many as four individuals were involved in the production of a woodblock print: the artist, who executed the original painting or drawing; the cutter, who carved the artist’s sketch after it had been pasted to a wooden block and then created the key or line block from which the color blocks were subsequently produced; the printer or rubber, who applied paste and water and inked the block to produce the print; and the publisher. The high quality of the rubbing is evident in Battle before Mt. Fuji: we can detect the grain of the wood in the rocky texture of Mt. Fuji, admire the exactness with which the red and yellow colors have been applied to the warrior thrusting a spear who appears in the foreground, and marvel at the printer’s deftness in producing an “edgeless” effect in his treatment of the sunset. To do this, the printer puddled water on the woodblock before introducing the red color, permitting what Kita describes as “a capillary action that would draw the pigment to the edge of the sky area.”

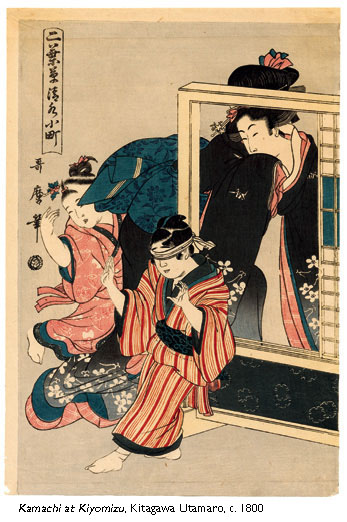

We also find in this first section a delightful example of artistic virtuosity. The exhibition includes a print of Kitagawa Utamaro’s Komachi at Kiyomizu (also known as Blind Man’s Bluff) and a later copy of this work. They depict two children playing, one of whom is blindfolded; a woman behind a screen watches their game. The print is from a series that portrays seven legendary events in the life of Ono no Komachi, a 9th-century poet. In this scene, there is an implicit comparison between the poet and the two-leaved plants of “little seedlings.” The seedlings in Japan are associated with children. The superior line work of the original is evident in the blindfolded child’s foot, with its more sharply articulated toe, as well as in the hands, neck, and ears of the figures. We can also see the grain of the wood of the screen in the original, a detail lacking in the copy.

Another stunning work, Katsukawa Shunsen’s triptych, Evening Glow at Ryogoku Bridge (ca. 1804—8), from the series Eight Views of Edo, exemplifies the technique of reportage, the artist’s registration of his perceptions. This work depicts a famous site in Edo, the Ryogoku Bridge, which teems here with bustling action—women in various guises, cavorting children, a peddler selling bowls of food, a man with a monkey on his back, and a smiling monk. All the figures are wonderfully animated and their garments richly varied. The background is just as detailed: we see people in their homes, figures in boats, and pedestrians walking across the bridge. Although large flakes of snow fall over the entire scene, the winter season does not deter anyone from coming out this particular evening. It is a wonderfully detailed account in which a moment of time is stretched large enough to hold a world of space.

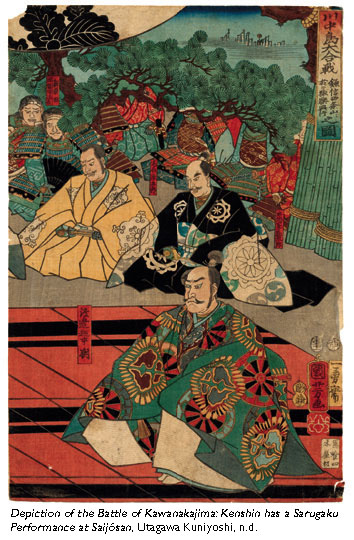

The second section of the exhibition, “Military, Court, and Legendary Themes,” features scenes from famous battles and figures from revered literary works, such as The Tale of Genji and The Tale of Heike, as well as from Kabuki plays. This part of the show offers a glimpse into the activities of the ruling class, especially episodes from real and legendary battles. Some of these figures hail from the early part of the Tokugawa Period (1600—1868). Once in power, the shogunate sought to consolidate its hold on society by reorganizing it, placing warriors highest, followed by farmers, artisans, and lastly merchants. Marginalized in this way, many merchants took refuge in the theater and brothel district of Edo. In the Floating World, the distinctions which held in the Tokugawa world were often overturned, especially toward the end of this period, when the samurai class became more impoverished. Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s Depiction of the Battle of Kawanakajima: Kenshin Has a Sarugaku Performance at Saijosan is one of the most suggestive prints in this section. Produced in the late 19th century, it constitutes a particularly provocative example of the “warrior” print. Kawanakajima was a famous battle of the 16th century. While five battles make up the Battle of Kawanakajima, not every one resulted in actual fighting. During the battle, Uesugi Kenshin, a daimyo, fought many times with Takeda Shingen. Considerable time was spent in negotiations, in which the two sides faced one another in councils, each trying to outmaneuver the other. These long standstills allowed Kenshin to mount a theatrical performance during a battle. “Saragaku,” which appears in the English title, is a generic term for a medieval drama, whether a serious Noh play or a comic kyogen performance. Hence it is unclear whether Kenshin and his guests are observing a Noh or a kyogen play. Kenshin, occupying the seat of honor, is in front, closest to the stage. Other warriors are seated nearby. From one perspective, the elements of the print seem drawn from the familiar repertoire of heroic representation. One could simply observe that Kenshin and his retainers are taking in a common pastime: plays formed common evening entertainments during battles, as they could inspire warriors or be prayerful occasions. But Kita sees a sly subversion in Kuniyoshi’s decision to depict the daimyo at a performance—an implicit rebuke of the Tokugawa Shogunate, which has declined from exemplifying the active heroism of earlier clans to embodying a gorgeous audience for the dramatic reenactment of such deeds. Kuniyoshi takes the stuff of legend only to reduce it to mere pageantry.

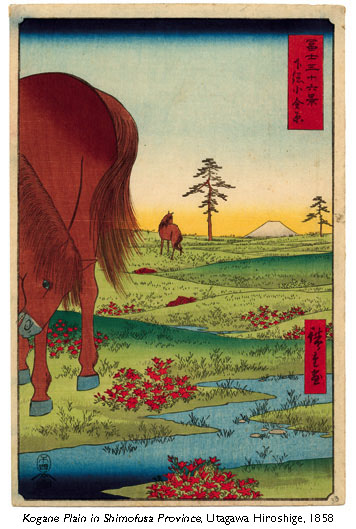

Ultimately, Kuniyoshi’s take on this battle constitutes a distinctive artistic vision, a keen desire on the part of the artist to render a particular perspective. This emphasis on portraying an individual vision of reality is one of the most notable features of 19th-century Japanese prints. The stronger the artist’s vision, the more he plays with “reality.” The exhibition’s third section, “Subverting Authority: Repetition, Deconstruction and Combinations of Words and Images,” boasts a bewildering gamut of themes and styles. Subversion here seems to have a very broad meaning. We find thematic variation in six prints by Kunisada that show a female figure standing in front of scalloped clouds, above which is a landscape. Read in sequence, the figures take on the shape of script, of a particular character. The representation flickers between image and word. Many prints include a poem or textual fragment which enhances the image or provides a different perspective on it. Some prints parody more traditional treatments of a particular subject. A case in point is Utagawa Hiroshige’s Kogane Plain in Shimofusa Province. This locale, dominated by Mt. Fuji, is one of the most famous natural sites in Japan and as such is the subject of innumerable prints. But here the mountain is barely visible in the distance. The title, which evokes but does not name the mountain, coyly underscores its insignificance in this image. What dominates the print is Hiroshige’s whimsical depiction of the hindquarters of a grazing horse. The artist capriciously evokes the sublime but reproduces the ridiculous. Many artists of the Ukiyo-e clearly revel in such broad humor, and Hiroshige here seems to indulge in a bit of self-mockery. The execution of the print is appropriate to the bathos of the image. Although Hiroshige is one of the great masters of landscape prints (along with Hokusai), this particular landscape consists of little more than a grassy field, far removed from anything majestic or picturesque.

The fourth and final section highlights the work of one artist, Yoshitoshi. The majority of the prints here are taken from two series, the brilliant One Hundred Aspects of the Moon and A New Selection of Eastern Brocade Pictures, which includes many scenes from Kabuki plays. The second essay of the catalogue, Stephen Margulies’ “The Enigma of Allure: Eastern Prints, Western Consciousness,” pays eloquent tribute to Yoshitoshi’s virtuosity. While Lane and his followers associated Yoshitoshi with the decline of Ukiyo-e, other writers consider him nothing less than a true visionary. Known for images of sublime beauty as well as shocking violence, Yoshitoshi is a startlingly original artist. As Margulies notes, “In Kuniyoshi, and his pupil, Yoshitoshi, intensity becomes, perhaps, an end in itself. There seem almost no limits to the vehement inventiveness of their imaginations, the adventurousness of their heroic sense of design and color, and the desperate beauty they achieve in preserving and transcending tradition.” Such sentiments echo John Stevenson’s three seminal books on the artist, Yoshitoshi’s One Hundred Aspects of the Moon (1992), Yoshitoshi’s Thirty-Six Ghosts (1983), and Yoshitoshi’s Women: The Woodblock Series: Fuzoku Sanjuniso (1988). In making the work of Yoshitoshi the culmination of “The Moon Has No Home,” Kita and Margulies roundly second Stevenson’s high praise of this remarkable artist.

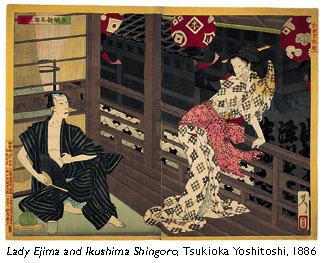

The diptych Lady Ejima and Ikushima Shingoro, from the series A New Selection of Eastern Brocade Pictures, exemplifies Yoshitoshi’s inventiveness. The print depicts a scene from a Kabuki play based on a notorious historical affair between Lady Ejima, a woman of the court, and Ikushima Shingoro, an Edo actor. Yoshitoshi captures brilliantly the tensions aroused by this liaison between an upper-class woman and an actor, which so scandalized Japanese society that the shogunate banned the performance of any plays dealing with the affair during the Takugawa, or Edo, era (1600—1868). Works which illustrated the mixing of classes were considered especially confrontational. On the left we see Ikushima seated, his body wracked with an emotion he barely controls. Lady Ejima, in contrast, is standing. Her twisting form, reminiscent of the sinuous S curve frequently seen in Italian Renaissance and Mannerist paintings, emanates passion and agitation. Her pose is no less anguished than that of her lover. Adding to the scene’s high drama are the effects of the wind, which buffets the pink sash of Lady Ejima’s kimono and the hanging lanterns. The strong geometrical lines of the architecture add yet another dimension of interest. Yoshitoshi, clearly undeterred by scandal, imparts a remarkable intensity to this scene between the two lovers. One has the impression of a clash between the ruling Tokugawa world of the warrior class, embodied by the woman, and the Floating World of the actor.

Lady Ejima and Ikushima Shingoro is one of two vivid diptychs taken from A New Selection of Eastern Brocade Pictures in this exhibition. The other is The Story of Jirozaemon of Sano, in which the courtesan wears a kimono featuring a dazzling array of colors. The very title of this series underscores Yoshitoshi’s brilliant use of color. The Japanese word for the kind of woodblock prints, characterized by the use of multiple colors, that originated with Harunobu in the late 18th century is “nishiki-e.” “Nishiki” means brocade, and “e” means picture, as noted above in the discussion of Ukiyo-e. Multicolored prints were so startling in the 18th century that they were called “brocade pictures” because they seemed as rich and sumptuous as brocade cloth.

Yoshitoshi was also capable of depicting scenes of great sublimity, as in Ishiyama Moon. Lady Murasaki, author of The Tale of Genji, here contemplates the majestic mountains which stand before her as she kneels on a balcony in the temple where she received the inspiration to write her great masterpiece. Playing upon her name, Murasaki, which means purple, Yoshitoshi has garbed the writer in a magnificent purple garment with a flowered pattern. The artist’s marvelous palette is evident in every one of the prints in this section. As in Lady Ejima and Ikushima Shingoro, we can see how the artist took full advantage of the aniline dyes which became available after the end of the Tokugawa period and Japan’s opening to the West.

No less sublime is Lady Chiyo, the lovely subject of the print which inspired this exhibition. The upper right corner of this print includes a poem which evokes an incident in Chiyo’s life in which she borrowed water from a neighbor one morning in order not to disturb the morning glories she discovered growing in her own well bucket:

- The bottom of the bucket

- Which Lady Chiyo filled has fallen out

- The moon has no home in the water

In Yoshitoshi’s print we see the fallen bucket with its missing bottom and the spilled water. Chiyo is the lone figure in this bleak landscape; the one bright spot is the lively flower pattern of her kimono. Although a full moon is visible in the sky, it is not reflected in the spilled water. Hence “the moon has no home in the water.” At the same time Chiyo holds her hands in a way that evokes the shape of the bucket. She seems mesmerized by the water that has spilled on the ground. For Margulies this enigmatic situation encapsulates some of the paradoxes which surround the art of the Floating World. Chiyo, Margulies observes, embodies the “seemingly contradictory meanings of water and of the Floating World—purity, instability, freedom, sensual immediacy, capacity for cleansing, heartbreaking ephemerality, clear reflector of truth.” So evocative and nuanced an art as Yoshitoshi’s, not to mention that of the other artists featured in the exhibition, amply testifies to Kita’s and Margulies’ contention that with the 19th century we have not so much a decline but a reflowering of Ukiyo-e. “The Moon Has No Home” recasts the spell which Japanese prints have wielded over the Western imagination.