There’s always something a little bit disquieting about seasoned masters of one field suddenly doing work of note in another. It makes the rest of us feel even more inadequate. Readers familiar with Charles Burns’s comics already will be well aware of the excruciatingly precise, razor-edged drawing with which he limns his stories of adolescent anxiety and dread; his ink-on-paper characters slip under the fishhook feathering of his stark lighting and sharp shadows with a surgical scrupulousness that makes the rest of us cartoonists cringe with inferiority. There is nothing murky or compromised in his work; “casual” and “careless” are words that evaporate from the mind when reading it. Thus, I was more than a little trepidatious when Charles mentioned to me a couple of years ago that he’d started taking photographs as a way of “relaxing” from the arduousness of finishing his decade-long 400-plus page project of formidable scope and emotional complexity, Black Hole.

I’ve been reading and studying and stealing from Charles’s work for all of my adult life, first encountering it in Art Spiegelman and Francoise Mouly’s RAW magazine in high school and carrying it with me straight through college and well into my own discipline every time I dip my brush into ink. I’ve also had the good fortune to get to know him personally, which has given me not only the opportunity to apologize for so sloppily ripping him off but also to occasionally benefit from his very friendly and reassuring company. I think, generally, people may be classed into two groups: 1) those whose uncertain movement through life is the result of their extremities flinging themselves forward or backward depending on how hard the world struck them the moment before, and 2) those who seem to be in possession of some mysterious gyroscopic governor which advances them past obstacles without any extraneous loss of energy or will. Needless to say, Charles belongs to this latter group. His presence, like his drawing, has a sort of solidity and certainty; he makes you feel as though if something disastrous or fiery or explosive were in the offing that he’d somehow be able to get you both out of it. His art shares this same sort of conviction; careful planning of every detail and rigorous plotting demand that each panel logically follow the other according to a carefully considered overarching flow of story.

The editors of the Virginia Quarterly Review initially asked me to discuss Charles’s surprising photographs in terms of and in opposition to such cartoonist-centric mechanics (i.e., the differences between seeing and drawing, the poetic juxta-position of images and other sundry talking points) and while I might be able to do a college passing-C job of it, I know whatever I wrote would also probably make Charles pretty nauseous. Charles is anything but pretentious. I don’t think I’ve ever heard him wax rhapsodic about the formal or theoretical aspects of anything. He’s more apt to tell a personal anecdote than to analyze, and he prefers artwork which is decidedly approachable if not downright “low class,” his sketchbooks filled with respectful studies of forgotten B-list comic book artists and pencil drawings that would startle anyone simply by their frenetic energy. (In fact, this is how Charles works, building up his pages from extremely loose scribbles which he then carefully refines and retraces until their essential, almost medical, essence can be preserved in his characteristic ink line.) He’s also an extremely generous and modest person. Anyone who went to any of his book signings for Black Hole last year received—free—one of these masterful original preparatory sketches which he individually mounted on pieces of cardboard. “Look, I’ve got literally thousands of these,” he told me when I scolded him for his largesse, while picking out the most elaborate one for myself. “Take two. Really—I’m serious. Take as many as you want. What am I going to do with them?” But he’s no savant; he just doesn’t feel terribly comfortable talking about the intricacies of his work, which is one of the more reliable signs (I’ve learned by now) of the real artist.

Charles attended three different art schools and colleges before securing his BFA in “something, I’m not sure what” from Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington, an institution of experimental learning that involved no grades as well as distinguished alumns Matt Groening and Lynda Barry. (Barry also knew Charles in high school, or rather, knew of him, describing him as “the school artist” and being afraid to talk to him because she didn’t think she was “cool enough.”) He then received his MFA in 1979 from the University of California at Davis, majoring in photography and doing what he called “double polaroids,” which were essentially portraits composed from two separately shot images. He also experimented with photo comics, though his final thesis show was sculptural, an assemblage of “underwear-related pieces,” with the appended self-assessment that it was “typical art school bullshit.” Because of his experience on the school paper with Barry and Groening at Evergreen, however, he’d started publishing comics and ended up in various newsweeklies in the early 1980s, eventually settling into this questionable field as his vocation.

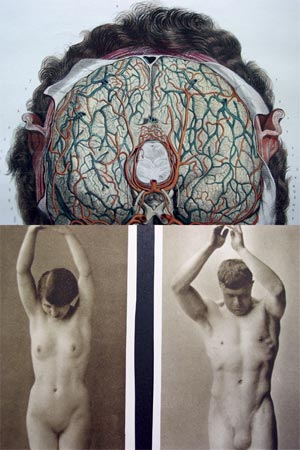

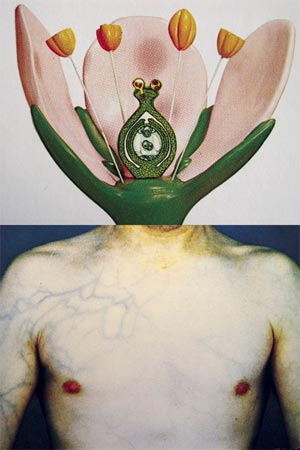

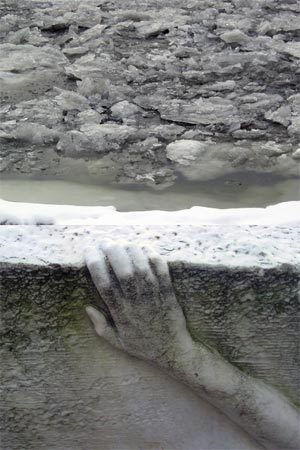

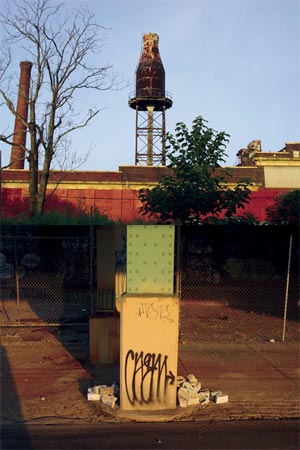

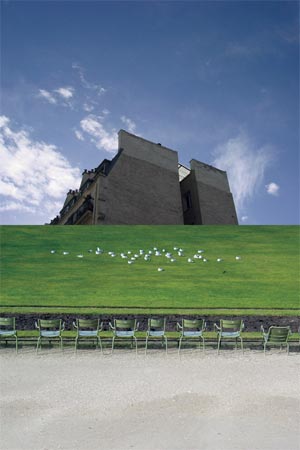

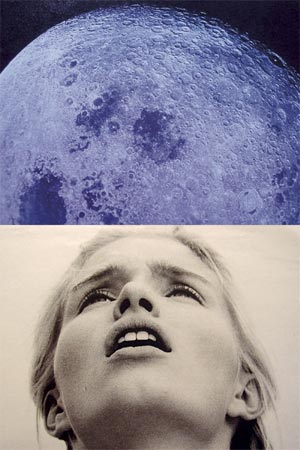

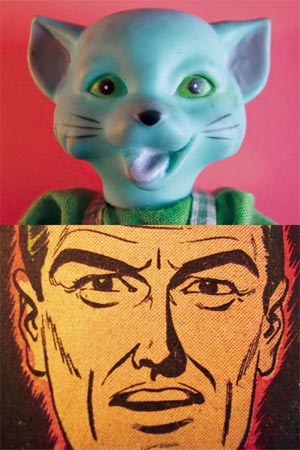

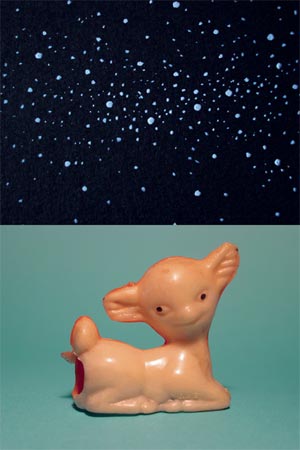

However (like thousands of other Americans), at some point about three or four years ago he bought a digital camera, and he found himself taking pictures again. Originally, he simply thought that the photographs would be a sort of informal visual diary or journal (with the added excuse that they got him out of the studio after focusing on painstaking drawing all day) but after they accumulated, he began experimentally arranging them into larger compositions. Originally, these were multi-panel constellations, not unlike comic book pages, but he eventually deciding to simply pair them. Occasionally, if inspired, he would go back in and add an image from a magazine, or photograph some object in his house. “It was just an exercise,” he told me recently, resisting a deep-think sort of interpretation of both his motives and the finished photographs. “Really, there are just three aspects to it: you take a picture, you take another and put it next to the other one, and then your brain makes something out of them, whether it’s a narrative, or whatever. You can also add a title, so that’s a possible fourth thing, but that’s it.”

While I promised I wouldn’t comment on the images that follow, I can’t help but say that they show a remarkably colorful range of feeling and a curious compositional acumen, revealing a side of Charles that I think he’s rarely presented elsewhere. On top of that, anyone who’s ever tried anything resembling collage knows that pretty much all but one or two roads lead to inevitable cliche, and Charles, I think, steadfastly maneuvers past those traps. And since I am full-fledged opining now, the “internal perspectives” that they suggest, while not alien to the sort of Sigmar Polke and David Salle paintings that both he and I were seeing in art school, are refreshingly approachable and unassuming. I find it amazing that although they originated simply as an exercise, they ended up both uncertainly poetic and certainly lucid, with a visual clarity that is characteristically Charles’s own.

—Chris Ware