The throbbing music emanating from Le Carnivore Restaurant behind our hotel grows tinnier with each tortured beat, the voices rising to ever higher levels of screeching, and although Darren and I feel exhausted from the twenty-four-hour flight from Boston to here, N’Djamena, the corrupt capital of the ruined African country of Chad, the merciless pulse of distortion refuses us sleep. We have no choice but to immerse ourselves until we are inured to the shrill bombardment and find, if not sleep, at least an accommodation with the noise.

Darren and I seat ourselves at a round table that tips beneath the weight of our elbows, sinking into the soft dirt floor. Ravenous cats dart about devouring meat scraps. We squint in the pale candlelight at murals of pink camels advancing ponderously through purple sand dunes. Dwarfing the murals are the jagged, lunging shadows of the singers. Players of trumpet, saxophone, banjo, and guitar sit ringed beneath a plastic valentine heart of colored lights and a neon wreath snapping on and off, on and off.

US oil workers shout over their sauce-smeared plates, on which a few French fries lie untouched. Their shadows bob, entwined with those of the singers in a crazed copulation. The singers themselves gyrate without expression as if they have lost all connection to the stage, as if they no longer exist except as a manifestation of the dead weight overwhelming me that in time might pass for sleep—when suddenly, amid trails of exploding static, their estranged voices are diminished to broken barks.

Women in bright orange and yellow dresses strut past the stage—unbidden and not the least distracted by this new failure in the sound system—to troll the oil workers. They escort them into the street one by one where the night absorbs them just beyond a fringe of blinking lights.

A young woman asks to join us and sits down without waiting for an answer. She orders a beer. Our dime. She introduces herself. Princess. A hairdresser and, she adds, a great soccer player. Perhaps she will leave for London and turn professional. What do we think?

Of course. Makes perfect sense.

“Do you want to go to a club?”

“No.”

She strokes little labyrinth swirls through the sweat-dampened hairs on my arm. I shake my head no.

She asks Darren to take her to our room for a back rub.

“No.”

Princess shrugs and finishes her beer.

“Where will you go from here?” she asks.

“Abeche.”

“And then?”

“The border.”

“With Sudan.”

“Yes.”

“We think of the Sudan border as people trying to solve an ethnic problem. It’s a private problem.”

She stands, pulls the plastic tablecloth from her hot arms, then kisses me on both cheeks, turns, and dissolves into the crowd. The thin scent of her hovers about my face until it, too, passes.

I ask a waitress for the bathroom and she points outside. Soldiers and security guards lounging on the backs of pickup trucks watch where I go. Not a star in the cave darkness of the overcast August sky that deepens ever blacker with storm clouds in this the last month of the rainy season. I slosh through puddles, disoriented in the gloom. I recognize one of the oil workers and ask him directions to the bathroom before I realize that he stands naked from the waist down, pants pooled at his ankles before a kneeling woman. She pauses in her ministrations, bloodshot eyes barely discernible in the depthless shadows, and pleasantly points the way toward the toilet.

“Thank you,” I say.

I retreat toward a dimly lit hall, abandoning her to her transaction in the secluded corner of a broken cinderblock wall. The damp imprint of my boots indicates that I, too, had fleetingly passed this way among supplicants seeking relief from the rigors of their exploitation.

“What do you do?” a man on our flight to N’Djamena had asked Darren.

A photographer for Getty Images, Darren answered only, “Journalist.”

“Oh. I do something counterproductive. I’m in oil.”

Back in Le Carnivore, I watch an oil worker prance on stage, exposing his buttocks to us bleary-eyed pilgrims, the boards quaking beneath the heavy clomp of his boots. Darfur and Chad and the plight of thousands of people lie lost somewhere beneath the abundance of money dispensed for drinks and whores and whatever other tawdry commerce might come available this night. Darren and I wave off the servers, mutely mesmerized by the obscenity of that jiggling white ass blurring before us as, slumped in our chairs, our eyes closing, sleep finally comes.

* * * *

Since 2003, millions of dollars worth of oil has been pumped out of Chad and neighboring Sudan, putting huge profits into a few well-connected hands.

In Chad, little if any of that revenue has benefited the country.

The Berlin-based organization Transparency International conducts an annual survey of the abuse of public office for private gain and measures the degree to which corruption is perceived to exist among a country’s public officials and politicians. Chad is tied with Bangladesh for most corrupt in the world.

In January 2006, the corruption became so apparent that the World Bank, which helped finance Chad’s oil boom, suspended $124 million in loans and grants, and stopped payment of an additional $125 million in oil royalties after the government resisted pressure to invest its oil profits in projects to aid its impoverished people, who survive on an average income of $30 a month. Chad’s president, Idriss Deby, threatened to shut down the country’s oil production unless the World Bank released the funds. The World Bank stood firm. Deby then demanded that Chad’s oil consortium, led by US oil giant ExxonMobil, pay at least $100 million to tide the country over until the World Bank released Chad’s royalties. US diplomats acted on behalf of American oil companies. Deby received his money, thank you very much, and the roads, hospitals, running water, schools remain little more than dusty dreams.

There could be no better symbol of his corruption than the one Deby himself has chosen for his political party, the so-called Patriotic Salvation Movement. The logo features an AK-47 assault rifle (the weapon that has ensured Deby’s power) crossed with a hoe (what better emblem of the poverty of those scratching out existence in rural villages?). Above it all floats an eternal flame, fueled by the oil that virtually assures the strong-arm tactics and fiscal dishonesty will never end.

Making matters worse is the unstemmed tide of refugees from Sudan. Divided between its Arab heritage in the north and its African heritage to the east and south, Sudan is cleaved along linguistic, religious, racial, and economic lines, resulting in civil war and ethnic cleansing in the Darfur region. More than 250,000 people, the majority of them civilians, are believed to have died in Darfur, and the United Nations estimates one million people more have been displaced. Already ranked the world’s fifth poorest country, Chad has in the past three years absorbed about 235,000 Sudanese refugees.

In April, a new twist came in the bloody, three-year-old conflict in Darfur. Sudan announced that its ABCO corporation—which is 37 percent owned by Swiss company Cliveden—had begun drilling in Darfur, where preliminary studies showed there were vast quantities of oil. A China-owned consortium already pumps over 300,000 barrels of oil a day from Sudanese wells. What might Darfur yield? Washington and the European Union had all but ignored the atrocities taking place there for three years, but now that the crisis threatened to disrupt the opening up of Sudan’s lucrative oil fields to Western companies the US started waving the threat of UN sanctions against Sudan.

As it is, there is no love lost in Chad for the government of Sudan. At the start of the Darfur war in 2003, Sudan armed Arab militiamen called the Janjaweed, many of whom came from Chadian Arab tribes, to quash a political uprising by Darfur’s black villagers who wanted increased autonomy—but the Janjaweed heeded no borders and occasionally led raids into eastern Chad. To this day, about eight thousand Chadian rebels maintain a camp in Darfur; earlier this year they fought with Chadian government forces sixty miles south of the strategic border town of Adre.

Last summer, to head off further fighting after the discovery of oil, the Sudanese government signed a peace agreement with the strongest of the rebel groups, but since the agreement was reached Darfur has grown more chaotic and violent. Meanwhile, Darfur rebel groups that did not sign the peace agreement have splintered and realigned, creating new ties and divisions that have made the conflict more complex and dangerous. Most importantly, a faction of the Sudan Liberation Army (SLA) and the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), an Islamist group, have joined to form the National Redemption Front (NRF), which claims to have gunned down Sudanese military aircraft. Some humanitarian experts worry that oil will only increase Khartoum’s resolve against the NRF in Darfur and encourage its a scorched-earth policy against rebels’ communities.

“No one doesn’t see oil as not a big element in all this,” a western diplomat told me, his words twisting into a careful knot of negatives. “Chad broke relations with Taiwan and sided with China. China has oil markets in Sudan. Is Chad trying to get China on their side so that Sudan will stop supporting Chadian rebels? What we do know is the Chadian people are not seeing any benefit from oil.”

* * * *

In the morning, Darren and I wander out, following rolling breaks of daylight in a desperate search for coffee. Mud clings to our boots. Women with their children sit on the ground hawking trays of cigarettes. Men fan mobile-phone cards in our faces, exhorting us to buy. Clouds gather. The air turns gray, cool, then still. Boys selling corn hold out their hands, look skyward, and run.

Curtains of rain sweep down upon us. The soft ground explodes beneath our feet, and dirt paths suck in the rain until the ground can absorb no more and the water rises back up through the saturated earth and stands in pools, spreading, consuming whatever patches of dust remain. The rising pools become streams, rage into torrents, sweeping up piles of garbage, sending it spinning past us. Harder and harder it rains, and the water rises and rises. Women with bundles of clothes strapped to their backs hold on to parked cars against the pull of the thick water. We stand on railings and watch, our weak coffee splashed by rain, clumps of curdled cream like bobbing islands.

After half an hour, the rain finally falters, then stops. We emerge from beneath a tin overhang and make our way back to the hotel past sodden vendors who peer with doubt at the still sky. Boys mince through the water holding their shoes above their heads. Mosquitoes spin madly in the gauzy sunlight. Almost immediately, the sun begins to burn the water off.

I call Djimte Salomon, a spokesman for the aid organization World Vision. He offers to drive us to the ministry for public security and immigration. We need permits to travel within Chad, a bit of red tape begun after an April coup attempt prompted an already paranoid dictatorial government to track all foreigners within its borders. The failed overthrow followed months of rising tensions between Chad and Sudan over the Darfur war. Chad’s President Deby comes from the same Zaghawa tribe as many Darfurians and has been accused by Khartoum of secretly backing rebels opposed to the Sudanese government by allowing them sanctuary in Chad.

“I am from the Sara tribe,” Solomon tells us, his car swerving on the slick mud streets. “If I killed a man, I would have to pay a fine. But if I was Zaghawa, I would pay nothing. Deby would protect me.”

Someone, however, wanted Deby to pay for interfering with Darfur. Chadian rebels attacked N’Djamena on April 13 but were defeated. On national radio Deby declared the situation under control, but residents, diplomats, and journalists reportedly heard shots for days afterward. Chad accused Sudan of backing the eastern-based rebels, some of whom appear to have been joining in Janjaweed attacks.

“They came early morning,” Solomon recalls of the rebels. “It was nothing planned. They had never seen N’Djamena. They had been too long hiding in Sudan. They got lost and asked directions for the presidential palace. The people were excited. Fed up with Deby. The rebels got confused and attacked the parliament. At one point the rebels’ truck died. They ran away and left mines and other ordnance in the truck. People came out to loot the truck and blew themselves up.

“Rebels, we don’t know what’s in their minds. I think if they get in power they will think, now it is our time to get rich. Just another cycle. The best thing, keep Deby and ask him to help all the people.”

He turns down a narrow street. Burlap stalls, drooling with rainwater, stand beside flooded fields where shacks slant in the unstable ground. Solomon says his job does not pay well enough for him to live like Deby and his henchmen, but at least he does not have to live underwater like the families outside our windows. He drives off the road to make room for a shiny Hummer barreling toward us.

“Stupid World Bank,” he mutters. “Can they not see? How does a man who earns less than $500 a month afford a Hummer?”

He rubs his fingers together, kisses them, and gestures toward a billboard of grinning Deby, beside Muammar al-Gaddafi, promoting oil development.

“That’s how.”

At the ministry, a drab cinder-block building where women sweep ankle-deep water out the door and into a flooded courtyard, a clerk tells us our papers won’t be ready until the afternoon. If then. Unless of course we pay additional fees. We refuse. The clerk shrugs. Chickens run down the hall past the clerk’s supervisor, a large woman with a pendulum walk who thrusts herself into the office and spills folders onto the desk. She asks our business and we tell her.

“What is the problem?” she asks.

“Nothing,” the clerk says. He gives us our papers. We walk back to the car.

“When do you leave for Abeche?” Solomon asks.

“Tomorrow.”

He starts the car. Rain begins falling.

“Don’t cross into Sudan. Journalists used to do that. Now they are arrested.”

* * * *

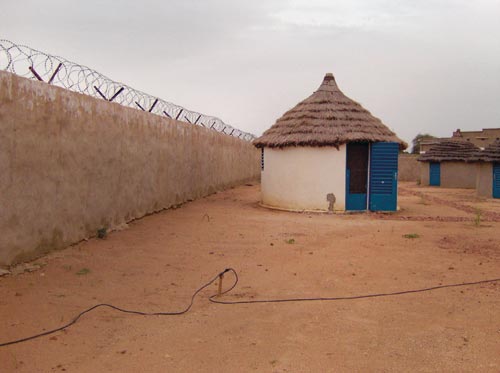

Darren and I arrive in Abeche aboard a fourteen-seat propeller plane courtesy of the United Nations. We wait outside the empty airport for our ride. Dusty streets. A few mud-brick buildings where dogs pant and soldiers in T-shirts and khaki pants sit with AK-47s balanced against their legs. Turbaned nomads with scarves across their faces ride their snorting horses like characters broken free from some myth to wreck havoc. A UN Land Rover maneuvers around the riders and stops beside us. We get in.

Our driver, Matt Conway, has been the UN flack in Abeche since February. The rain has kept things quiet, he says, but we can expect the fighting in Darfur and skirmishes between the Chad army and Chadian rebels to resume when the rains stop.

We turn down a rutted street toward the UN compound. Nothing on either side of us but aid organizations. A circling of the wagons against what lies beyond this alley.

“Journalists from National Geographic were jailed for crossing into Sudan from Chad earlier this month,” Matt says. “They probably went in with the faction of the Sudanese Liberation Army that signed the peace agreement.”

“And were betrayed by them?”

“Yeah.”

“To score points with Khartoum?”

Outside a pair of towering spiked gates Matt brakes the Land Rover and honks. A guard opens a panel and looks at us. Then the doors open and Matt drives through. All that’s missing is the moat.

“Everyone is just out for themselves, man,” Matt says. “It’s all about survival.”

* * * *

Matt’s office. Paper-strewn desks. Computers humming off generators. Maps on the walls. Circles indicate “areas of concern” in eastern Chad.

Abeche, where we are: “Degradation of the security situation in town ongoing.”

Bahai: “Presumption of recruitment by Sudanese rebels in the camps.”

Guereda: “Permanent Sudanese and Chadian rebels’ or bandits’ threats.”

Farchana: “Permanent risk of military confrontation.”

With my fingers I trace the arrows and circles and small dots for towns. Tomorrow we leave for the Farchana refugee camp. Mustapha Mohammad, a thirty-five-year-old man whom Matt recommended as an interpreter, stands beside me, his shaved head tipped back as he contemplates the map. He was born in Abeche, speaks English, studied in Khartoum, and knows Arabic. He worked for the Chinese-owned Great Wall Drilling Company in the oil fields of southern Chad. A radio operator. He still has his ID tags, shows them with pride.

“Bad?” I ask.

“No, nice map.”

“I mean going out to the camps. Too dangerous?”

“No, not too dangerous. Not for me.”

“And me?”

“For you, little bit dangerous.”

I tell Mustapha to meet us at eight o’clock in the morning.

“I give you African promise.”

“What is that?”

“You tell me to meet you at eight o’clock, African promise means I will see you no later than nine o’clock.”

“Meet me at seven.”

We can’t leave, however, until we register our travel permits with the local chief of police, still referred to, in this former French colony, as the “commissar.” His secretary sits behind a wobbly wood desk. A broken, dust-covered typewriter and an ink-cartridge box take up a corner. He looks at our papers, mutters, reads them a dozen times, asks when we arrived. He takes a stamp from a drawer, presses it into an ink pad. He grinds our papers with the stamp so thoroughly he leaves a stain on the desk, examines his handiwork, blows on the ink. Satisfied, he advises us to wait for the commissar.

We stand outside, on the windblown road where beggars lie in ditches and raise wrinkled arms to all who pass them. Empty oil cans collect rainwater. The commissar pulls up in a Suzuki Jeep. We follow him into his office. Dank, white walls, dirt floor grimed with chicken droppings. He tears into his secretary for not having our papers numbered correctly. He reviews the stamps and signs his initials. He points out the Louisiana flag he has on his desk. He studied at the Baton Rouge police academy. He gives us our papers, on which the ink is still damp. He warns us against going out at night. Bandits. He asks if we like jazz.

“Yes.”

He smiles and nods and follows us to the door. Through the rear window of the Land Rover I watch him. He grows smaller waving the Louisiana flag.

* * * *

We begin the three-hour drive to Farchana with Claude, a retired Canadian marine in charge of overseeing the “gendarmes”—Chadians hired to provide security for refugee camps. The UN pays the gendarmes a monthly incentive fee of $150 to offset their paltry $64-a-month government salary. This arrangement was intended to motivate the gendarmes and provide a firewall against bribes from rebel forces. Unfortunately, the plan has backfired. The gendarmes effectively hold the UN hostage for ever-increasing incentives, and the UN has little choice but to pay up, if it wants to maintain camp security and ensure the safety of its personnel. The Deby government happily encourages this lopsided relationship, as it allows the government to avoid spending oil profits on maintaining the cronyism that passes for loyalty within its ranks.

Meanwhile, the gendarmes do little more than escort UN personnel—without raising a finger to actually protect them or the refugees in their camps. Before Darren and I arrived in N’Djamena, Chadian rebels kidnapped four thousand men and children from a UN-run refugee camp near Goz Beida in the south. The gendarmes did nothing. Thirty-five NGO vehicles have been stolen since November of last year; UN personnel have also been assaulted in carjackings and burglaries. Again, the gendarmes have done nothing. So all travel, even under supposed guard, is understandably tense.

We follow a dirt road out of Abeche and into the brush toward Farchana. Our driver stops at checkpoints where our papers are inspected and laboriously stamped again, our names recorded on curled sheets of paper dusted with the ancient import of the old men writing on them. Scavengers had passed this way before us and dug up the bones of cattle and goats and camels and other animals whose shined skulls leer at us in the glare. We turn north on a narrow dirt road crushing scrub brush under our wheels.

Claude talks without end, his voice amazingly steady despite our being tossed about by the deep ruts we hit and our driver’s insistent speeding. “The camps are better organized than the towns around them,” Claude says. He raises his hands against the roof for balance against the bumps. “They are jealous, these towns, but they don’t understand. This is not home for the refugees. They can’t work. They have small living quarters. I’m going to see how the police are doing. Sometimes there are small problems. Like they beat people.”

We stop at a soupy brown wadi—Arabic for a dry riverbed—filled with roiling rainwater. Boys whip donkeys with switches and the donkeys bellow their protest and refuse to cross the frothing waters. Nomads on camels pause at the edge of the water and let their mounts drink. Toll keepers ask us for money to grow grass and keep the shoreline stable. I look at the crumbled ground without a hint of greenery.

Okay.

Boys shovel dirt into the sandy craters swallowing the wheels of another Land Rover ahead of us. Our driver drops a Central African franc, worth about twenty-five cents, out his window to them. The boys scamper after the limp paper bill, swinging their shovels at one another. The wind teases the bill just out of reach until it vanishes in the mottled dusty air and drops invisibly into the water.

The toll keepers advise us to drive straight, don’t stop. Our driver backs up, guns the engine, and, picking up speed, takes a running start toward the wadi. Water explodes in all directions and we’re thrown against our seats and the Land Rover plows forward and we feel the resistance of the water against the grille and we feel our tires spin madly and we see the muddy slough rise to the doors as we sink, brown geysers jetting outward like wings of a bird, and we pass another Rover roped to complaining mules in the middle of the wadi, and we pass naked men lined chest-deep in the water, encouraging us, and we grind on, humping up the opposite bank sluicing water and mud, emerging triumphant onto land.

“We don’t have much time,” Claude says, inspecting the sky. “See those clouds. They are nothing now. But tomorrow. We have until tomorrow afternoon or we’ll be stuck for days by rains, because the wadi will be too deep.”

* * * *

Five-year-old Mukhatar Ahmad stares at me from his parents’ hut in Farchana refugee camp. His right eye protrudes white and glassy from its socket. He does not talk. He will not tell Mustapha how his eye was damaged. Perhaps playing with other boys, one woman suggests. Perhaps he was born like that. Flies suck at the eye. Mukhatar does not blink. Faces balloon and shrink, huts curve, reflected grotesquely in his eye.

Three years he has been in this place. The weight of time, the slow drain. He pours water from a heat-swelled oil jug.

I am here because of war. I saw fighting, killing by helicopter, by guns. Militia of Janjaweed. I saw dead. I can’t describe it. Because of this problem we left Darfur.

Mukhatar moves his head and I follow his dead eye, the world turning in its silent orbit. Mountains green from rain. Women carrying buckets of water on their heads. Goats kicking at the dirt.

They shoot people in the head. I stayed in my village. Hid in my room. Saw through window. Many killed. I hope I return. The situation is worse here. No money. Not enough food.

A child takes my pen, tries to suck the ink from it. Boys drag toy trucks made from the rusted tin of sardine cans. Toothpicks as axles. Tires of mud. Putrid heat within the tents, where they play despite their parents’ apathy. Pallets of dirty blankets. The boys hold their toys for me to see.

War came in three ways. Some war by helicopter. Some by the Janjaweed on camels. Some by soldier in trucks. They attacked in the morning. Many times come with guns and shoot. We were in school. Some escape, not all.

“We must go,” Claude says.

The UN has rules. All of its people inside by four p.m. He stands to leave, and I step out of Mukhatar’s compass, leaving the globe of his eye to the flies. He watches me go, his hand raised, outstretched fingers ready to clasp my hand if I offer it to him. Take me with you, he seems to say, but his lips do not move. Just that eye in its blindness following me. Take me with you.

* * * *

We make the three-hour drive back to Abeche the following afternoon and beat the rains by just under an hour.

“This would have stranded us at the wadi,” Claude says.

We sit in a screened-in building that serves as a cafeteria. I nod, pick at my plate of rice and beef liver.

“Oh, that would have been awful,” tut-tuts Rodolphe, another security man who monitors the gendarmes in northern Chad. He served more than twenty years in the French foreign legion. He looks well into his sixties. Shaved head, trim and taut as a wire.

Rain slashes through the screen. I wipe the water off a map Darren and I are consulting. We want to drive north to Guereda, spend the night and continue to Iriba and then Bahai in the Sahara Desert. Then drive south to the border town of Adre.

“Impossible,” Claude says. “No roads from Iriba to Adre. And what about water, what would you do about water?”

“Carry it.”

“You’d have to carry a well. That’s the Sahara, man.”

He traces a dirty fingernail from Abeche to Guereda. The road is bad, he explains. It will take us at least five to six hours. He cannot say that it is safe. In the past few days, more than one hundred Chadian soldiers were deployed in Guereda. The drive from Guereda to Iriba would be very bad. Even UN convoys do not follow that route.

“Bandits, man, when you pack your gear they know where you’re going,” Claude says. “Why do you think you fill out all that paperwork? Information is passed along.”

“At first,” Rodolphe adds, “they won’t know when you leave here. But when you check in at Guereda, then they’ll know. Travel with others. Don’t discuss plans with your driver or translator. What’s their tribe?”

We shrug.

“My God, you don’t know! Always know people’s tribes. The president is Zaghawa. If your men are Zaghawa nothing will happen to you because they are part of president’s tribe. But if they are Tama don’t go. A Sudanese tribe. No one likes them.”

“Why?”

“They were strong once like Zaghawa.”

“Any other tribes that would be bad?”

“No. Just Tama. Give me your names.”

I write them down. He scowls at my handwriting.

“I will notify the prefe in Guereda you are coming. Villages are still run on the French administrative system. The prefe is the administrative leader. He will protect you once he knows you are there.”

He examines our map.

“Bahai is a hot spot. The main road from Sudan to Guereda goes through Bahai. A rebel route. At night many things happen. Four people on camels shot up Kounougo camp in Guereda two nights ago.”

“Why?”

“Why not? It’s a war, man.”

* * * *

In the morning, we sit outside the cafeteria and wait for Mustapha and Abdullah, the driver we hired. Rodolphe stops in for bread and cheese. He flies to Guereda in a few days to organize security for a visit from US Senator Barack Obama.

“That senator must be an expert on Chad,” he says. “Two hours in Guereda and he will know everything. I wish I could work for him. Maybe I will see you, eh?”

He stuffs bread in his mouth, interrupting his laughter.

Mustapha waves to us from the gate. I call him over.

“What is your tribe?”

“Masalit.”

“Abdullah’s?”

“Masalit.”

“Not Tama?”

“No. Why?”

“No reason.”

* * * *

We drive through the rain-cooled desert. A thin layer of green scrub grass stretches across the sand. The seething, clay-colored waters of wadis carve the land into an irregular patchwork of dunes and bare trees.

Men and women pause to watch our passage, moving between their morning cook fires. We wave and they raise their arms and the children chase our dust, shouting for candy.

“Is that a baboon?” I ask Mustapha and point to a red monkey squatting below a tree.

“No.”

“What kind is it?”

“We have three kinds of monkey. Small, bigger, biggest. That one is small.”

“Thank you.”

A flock of gray African quail crosses the cattle trail that serves as our road. Abdullah accelerates. The quail scurry and begin squawking and I hear one of them thump beneath our Land Rover. Abdullah takes a knife off the dashboard and runs back a few yards looking at the side of the trail. He pauses at a clump of weeds, knife raised, then makes a slashing motion. He looks up smiling and carries the dead pheasant by its feet.

“Dinner,” Darren says.

* * * *

The administrator of the Guereda compound is out, a guard informs us, so we decide to check in with the chief of the gendarmes. We ask directions of some men on the street. They look inside the Land Rover without answering. The look at us, reach with their hands but decide against touching our clothes. Finally, one of them points down the road to a clot of square mud buildings.

The security chief paces behind a desk, above which hang pendulum-shaped beehives. Black wasps circle our heads. An aide sleeps on a cot. The security chief examines our papers upside down, lips moving. He stamps them with heavy deliberation, applying his whole body as he leans over the stamp. He blows on the ink, signs his initials, holds it out as if determining its suitability for framing. He tells us to return to the UN compound. He will bring the prefe to us momentarily.

Emmanuel, the compound administrator, meets us at the gate. His red-rimmed eyes speak of sleepless nights, of nerves on edge.

“How did you get here? Drive?”

He doesn’t let us answer.

“How long will you be here? My God, you came through the jungle. Since January, rebels have been attacking Guereda. Since April NGOs have lost six vehicles to road bandits. We have had attempted carjackings on two cars. A policeman was killed, another injured.”

He pauses, breathing hard. A Rwandan, he survived the genocide there by escaping into the compound of an aid organization. All of his family was killed. He survived only to be kidnapped here in February by rebels. They held him for forty-five minutes before he was released. Looking at him, I realize he lost more than just forty-five minutes. He must have thought Rwanda had finally caught up with him.

“We don’t talk of curfew, but after four o’clock we enter our no-movement phase. We don’t leave the compound. Six hundred soldiers arrived two days ago. They were promised since April. Maybe they are here because of the US senator. I don’t know.”

He fusses with paper on his desk. A fan scatters the papers and his hands scramble after the fleeing memos and lists of protocols.

We step outside the compound, look at our watches. Where’s the security chief?

Two men lounging on the ground beside a blanket buried under pots and pans tell Mustapha that rebels came through yesterday, but did not bother them. They were after soldiers.

We walk away, but I feel the two men watching us.

“They won’t tell you, but there is much violence here,” Mustapha says.

“How do you know?”

“They are Tama tribe. This was Tama territory. Before, each family of Tama have two hundred to three hundred cows. They were destroyed by Zaghawa. Before, you would see hundreds of camels and cows on the road to market. Now nothing.”

* * * *

We tire of waiting for the security chief and decide to see the prefe ourselves. The two Tama men point us down a rock-strewn road toward a building that resembles a mosque. Giant vultures perch in vast nests that consume the tops of the trees. They stare down at us with their red faces and featherless necks.

The brown-robed prefe sits alone in a room equipped with only a rug.

“Go back to the UN and make your plans,” the prefe tells us in a voice somehow disconnected from his jowly face.

Outside the vultures have roused themselves and circle overhead.

“The prefe knows nothing,” Mustapha says under his breath. “He is a stupid man. He can’t read, can’t write, but he is of Deby’s tribe.”

An hour later, Mustapha comes to our room. The security chief came by. Pissed off. We should not have seen the prefe without him. Now, he informed Mustapha, we cannot visit the camps.

* * * *

Middle of the night. Lights out. Our breathing in the dark. Darren complains the pheasant was tough. Mosquito net heavy on my face. I hear the little fuckers buzzing, wanting me. I need to piss but dread the outhouse. The fetid stink. The flies. The lumbering black beetles.

Pop, pop, pop.

“You hear that?”

“Gunfire.”

“AKs.”

“Maybe.”

Pop, pop, pop.

“More.”

“Yeah.”

“I have to piss.”

“Can’t help you.”

* * * *

The security chief meets with Emmanuel in the morning. Darren and I sit with Mustapha and Abdullah. We wait to see if he will relent on grounding us. I understand we bruised his ego. By meeting with the prefe without him, we effectively said he doesn’t matter. The prefe, too, was insulted. We violated protocol, cut around the chain of command and strode without escort into his inner sanctum.

“You should not have seen the prefe,” Emmanuel scolds us. “I have spoken with the chief of security. He understands you are new so you won’t be punished.”

“Punished?”

“Jail, thrown out. It doesn’t matter. He will escort you to Mile camp.”

An armed convoy of Toyota pickups filled with gendarmes holding rocket-propelled grenade launchers and machine guns waits outside the compound.

We reached Mile camp by midmorning. I see women and children swarming to a hospital tent for free milk. Most young men were either killed in the flight from Darfur and Chad border towns or have joined a rebel militia.

A boy with “sla” printed on his sandals stops me. Slung over his shoulder is a butchered goat. Blood runs down his back. He looks at the soldier-filled pickup, just feet away, and laughs.

“We have no security in the camp. Sometimes at night the Janjaweed attack doctors. Sometimes shoot guns. In all of Chad there is no security.”

He points to the letters on his sandals.

“Before we are refugee we are Sudanese. We support the opposition to the government. After the rains, there will be fighting. We wait for fight.”

He walks away, the head of the goat flopping. I tell Mustapha we should leave. We need to return to Abeche for the night and then in the morning drive to Adre, an hour east of Farchana, where we will spend the night. No roads run from Guereda to Adre so we must backtrack. No hurry. Leave in about an hour. African promise. I laugh, slap him on the shoulders. Mustapha nods but doesn’t smile. His eyes follow the goat’s blood trail.

“There is no promise,” he says. “Especially in Africa.”

* * * *

“Mustapha, tell Abdullah to slow down.”

“What is the problem?”

“Those are goats.”

“It is good.”

“I can handle birds, no goats.”

“Maybe one.”

“We are close to Abeche. We’ll eat there.”

“Abdullah, drive slowly.”

* * * *

After a night in Abeche, we return to Farchana on the way to Adre. We stop for bread and sardines. Mustapha and I drink tea. I lean against the wall of the tea shop. Suddenly my back burns. The pain increases. I take off my shirt and my back has exploded with welts and red slashes as if I’d been whipped. No one knows what has bitten me. I fight panic, feel my heart race. I want to spin in circles and slap at my back. Mustapha applies across my back a mud poultice mixed with wet tea leaves. It helps. The welts recede. We need to continue to Adre. My back itches. I swallow a fistful of Benadryl tablets.

* * * *

In Adre, road signs fallen in the soft sand point the way to Sudan. Across a wadi where children splash in the water, we see the rough hills burned brown in the sun, and cattle spot the hills close enough that I can see their bent heads scouring the ground for grass.

“El Geneina,” Mustapha says. “Sudan.”

“We can’t cross over,” I remind him. “Always know where the border is. We’ll get arrested.”

Abdullah drives into the town center. Armed soldiers expressionless behind their sunglasses monitor the roads. People stop what they are doing to watch us. The vendors selling car tires. The women washing clothes in buckets. The boys chasing one another down the narrow streets. Sheep stand behind a butcher stall and the butcher watches us, too, sharpening his knives.

We drive past walls cluttered with faded oil-company advertisements. Children and goats stand by mud stoops, and vultures observe the commotion from the branches overhanging vendor stalls. Rap music carries faintly from cassette players. We pass a herder of goats, the animals wide-eyed due to the clanging of metal coming from one of the huts; there an old man beats shapes out of metal that is orange from the light of a forge fire.

We stop at Adre Hospital. Guards lounging within the crevices of broken walls rouse themselves and lead us to the main office, where we meet Dr. Autid Adam.

“Patients live under trees. Many injured. Many refugees. No medicine, no doctors. Shooting injuries. Situation not good. It is too difficult. All is lost.”

He calls an orderly to escort us through the halls. The soles of my boots stick to the floor. Flies collect on discarded bandages. Women sit outside dimly lit rooms, passive to the flies scrambling across their faces. One of them grabs my hand. Her boy. There. On the plastic brown mat where dirty sheets peek out from beneath a mosquito net. That boy. He fell from a tree, fractured his left leg. The cast won’t dry in the humidity.

Across from him lies another emaciated boy with a gunshot wound to his left hip; it is clotted with flies. My stomach turns. The funk. Soldiers shot him in June or July. He can’t remember. Shot here in Adre while working in a grain mill. Janjaweed attacked his village in Darfur in 2003 but it was here he was shot. He smiles. I clamp my hand over my nose and mouth against the smell, try to convey with my eyes that I appreciate his sense of irony.

Another boy. Shot in the buttocks in January by the Janjaweed. He lies on his stomach, urine bag spilled on the floor. A nurse steps on it, shakes it off her foot.

A fat bandage covers the boy’s wound. It hasn’t healed. The doctors don’t know why. Perhaps the heat. Perhaps the lack of medicine. Perhaps it is just bad luck. They shrug, helpless.

“What are you doing here?”

I turn and face a doctor with Medecins Sans Frontieres. We don’t have his permission to be here. This part of the hospital belongs to MSF, he says. Do we not understand the danger we are in? Have we not seen all the soldiers? Everyone is watching everyone. Even now, as we speak. My God! No one is safe. MSF cannot be seen associating with us. What if we offend the Chad government? What would happen to his work then? If we want to talk to “the blacks” we must go over there.

He points to a collection of dejected buildings, a courtyard where fowl nod in the afternoon heat beside men and women sprawled beneath gnarled, leafless trees.

“I don’t know what they do there,” the MSF doctor says. “The blacks operate that. It is not MSF. You can go there if you must.”

“Even if we offend the Chad government?”

“This is very dangerous. A war. You put yourself and us at risk being here. You must leave our side. I will talk to Doctor Adam.”

He spins around and stalks down the corridor, trailed by a nurse. Black orderlies in white coats follow at a respectful distance.

* * * *

We leave the hospital and follow a rutted street draining sewage. Our windows open, dust blowing in. Wide-eyed children stare from open doors that lead into darkened halls wet from mop water. Squatting men eat with their fingers from tin bowls. The air stands heavy with the funk of cows and goats and sheep that have passed this way to market. Many of the mortared huts provide empty reminders of the dozens of families who lived here once.

Abdullah parks outside the compound of Secedev, a Chad NGO that provides agricultural assistance. We get out of the Land Rover dust-covered and sore. Inside the gates, a man scoops pasta onto a large plate. He inserts spoons all around the plate and the staff and we sit in a circle on the ground and dig in. Flies ignore the food, descending instead on us.

“Janjaweed come together in great numbers and attack and take the animals of farmers,” Ndoyengar Narisse says after I tell him about the MSF doctor. “It is very insecure. The SLA is in Adre. Sudan troops are in the hills across the wadi. This morning we go to Goungour, less than a mile from the border. The security there is okay, but villages near it have been attacked and all the people flee to Goungour.”

We drive forty minutes through the bush, following Ndoyengar, the soft sandy ground sucking at our wheels. Some spots are lushly green from rain. Goats rise up on their hind legs to graze in leafy trees, and farmers till the ground in fields of sorghum.

In Goungour village, fencing made from twisted branches encloses empty corrals; dust churns up from the bare feet of children fleeing our advance. A generator hums through the warm, wet air. An old man lays straw mats on the ground. We sit and he pours mud-filmed water from a plastic National Diesel Oil jug into a bowl.

“This is our water,” Ndoyengar says before he drinks. “Taken from the wadi.”

The village elders join us to share the water, their cheeks drawing in like the gills of a fish with each sip.

“This is the biggest village in this area. We had a police station but the police left for Adre.”

“There’s no security now.”

“Yesterday the Janjaweed took twenty-six cows.”

“In July they took one hundred fifty cows and eighteen camels.”

“They always come back.”

“On horses and camels. White turbans. Sunglasses. Khaki pants. Rifles.”

“They look for villages with animals.”

“We miss our cows.”

“We miss our land.”

“We miss the people who are dead.”

* * * *

The afternoon creeps up on us without warning. We leave Goungour, return to Adre then Farchana before nightfall. Ndoyengar takes us by another route he says is faster. My stomach turns. Perhaps from the water. The sun swims in the sky, rainbow rings throbbing from it with each hole the Land Rover strikes. I drink from my water bottle, which I left too long in the heat. I’m woozy from the Benadryl, mouth pasty. My back itches. I bounce from my seat, flopping like a marionette as we hit another hole.

What is that? A ravine? We dip into it, drive ahead. Or is this the border wadi? Are those hills Sudan? Where the fuck is Ndoyengar taking us? The heat. I’m burning. I drink more water. I don’t know Ndoyengar. Is he taking us to Sudan? More rainbow rings. Oh shit, what’s going on? How much can he get for us? Yellow sky, Arizona desert, except those are not Apache warriors on the sunned buttes. No, they’re Janjaweed. Oh Jesus, tv fucking Westerns, what am I thinking? The skull of a cow. Its sightless eyes hold the sky and me in it. Jesus, is he taking us into Sudan? Why can’t anyone hear me? Where are we? Where are we?

“Stop, stop! Stop the fucking car!”

Abdullah stops, looks uncertainly at Mustapha, who reaches for my hand.

“What is wrong?”

Ndoyengar drives on then he stops. He gets out and walks back to us.

“Where are we?” I ask, my voice coming out in gasps. “Why are we crossing the wadi into Sudan?”

Ndoyengar scowls.

“Sudan is a mile away. What is the problem? I have work to do.”

He walks back to the Land Rover. Abdullah starts the engine. I sip more water. Hot wind dries my face. I’m sweat-soaked. My back itches. I pop a few Benadryl and close my eyes. Day-tripping. Let the land take me where it will.

* * * *

We spend the night in the Farchana compound and then return to Abeche in the morning. After we stow our gear, Darren and I join Claude in the cafeteria. There’s a bottle of beer on his table.

“The gendarmes say they need an increase in their incentive pay,” Claude tells us. “The UN has approved a 6 percent increase. We’re worried it will become a subsidy. It’s already more than their salary. We’re not sure how much of the salary they use. They might just sock it away.”

Darren and I buy beers.

“The UN voted to deploy troops to Sudan. But Sudan won’t accept them. So …”

Claude throws up his arms.

“There’re rumors of a new offensive in Darfur,” he continues. “Who knows what will happen now on the border. Will the rebels flee into Chad? Will Deby let them? Does he have a choice? The border guards and rebels are all from some tribe. If Deby lets them stay, will Sudan support another coup attempt?”

He pauses to sip his beer.

“It’s about oil. There’s oil in northern Sudan, oil in southern Sudan, chances are there’s oil in the middle. Move out black Africans and put Darfur under Arab chiefs and the oil is theirs.

“It’s about Arabs versus black Africans, herders against farmers, Darfur population versus Khartoum leadership. But don’t forget the oil.”

* * * *

In the morning we fly to Bahai, where the Oure Cassoni refugee camp was established in 2003, literally feet away from the Sudan border in the Sahara Desert.

Beneath the wings of our plane the land transforms from a thin layer of green to rolling sand dunes. We land on a rock-strewn runway and stop beside a shack with a torn tin roof that is rattled by bursts of hot wind. A UN Land Rover awaits our arrival.

An African gazelle, a gift from the village elders, sits in the sandy lot of the Bahai compound and watches with wide dark eyes as we swing by it and park in front of the administration building.

The compound’s administrator, Comlan Spero Guy, offers us chairs. He asks his assistant to provide us with a security briefing.

The people of Bahai are Zaghawa. The camp is twelve miles from here and less than a mile from the border. We travel in convoys only, at least three Land Rovers. A six p.m. curfew is in effect. Be careful of looking at Zaghawa women. The men will harm you if you approach their women. If you kill a woman, you will pay at least one hundred camels. A man, you will pay countless camels. Understand?

“Where would we get the camels?”

“Please, just try not to kill anyone.”

“Right.”

“It is very hot. The winds are dangerous here. Sandstorms cover the sun. What else do you wish to know?”

“You tell us.”

“It is not easy to distinguish rebels from soldiers. They have the same guns, wear the same uniform. But no one will admit this to you. Chad and Sudan have an agreement. Chad is not to support the rebels, Sudan is not to undermine Chad’s government. We will see, eh? Just on Sunday we saw Sudan forces deployed on the border, watching the camp. There may be some Janjaweed there as well. Questions?”

* * * *

After lunch we drive to Oure Cassoni through a treeless desert landscape like the bottom of an ocean. Diesel-spewing jeeps loaded with armed men pass us. Some of the men wear desert military garb, others T-shirts and khaki pants. Rebels? Soldiers? Both? Who can say?

The camp sprawls for miles, the tents so covered with sand that at first I mistake them for dunes. Unlike in the other camps, I smell nothing. Instead the still air feels as vacant as the stares from families who sit immobile outside their tents in the harsh light.

We stop at the market where the Shell insignia glints off aluminum siding used on some of the stalls. An elderly man offers us tea. Beside him other men take off their argyle socks and pour water over their feet in preparation for the time for prayer.

“My tea shop is called Gahwatu Alatilleen,” the old man tells us. “It means if you have no work, come here.”

He laughs. A young man approaches, asks where we are from.

“America.”

The old man is his uncle. The young man, twenty-five-year-old Izeldeen Khacter, shows us a business card from Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“I have worked with doctors from this place.”

“I want to talk to the rebels,” I tell him. “I want to know what is happening in Darfur.”

“Yes, you can do this. Come.”

We follow him out of the market toward his tent in Zone C, Block L. The camp is divided by villages and tribes; Zaghawa, Fur, Masalit, Grron, Dagno.

In Zone C live families from Furawiya, Sudan; Zone A, Korunie City, Sudan; Zone B, Awmrow, Sudan.

Izzy left Furawiya with his parents days before the Janjaweed attacked it. From the road to Oure Cassoni camp, he could see Furawiya burning.

“I have no work papers. I only have refugee card for food. People say, Since you are Zaghawa won’t Deby help you? In New Orleans, people were American like your President Bush. Did he take them in?”

We stop at a tent that serves as a small library. Izzy manages it every morning. He attended university in Tripoli where he learned English. Inside, he retrieves a Thuraya satellite phone.

“Tonight I will call people in Sudan to speak with you tomorrow.”

“How do you know the rebels?”

Izzy shrugs.

“Are you a rebel?”

“If I support George Bush and another man supports John Kerry is that man a rebel? That is me. In America I would support John Kerry. I don’t support Sudan government, but I’m not a rebel.”

* * * *

Evening at the Bahai UN compound. Vast blue-gray sky tinged with the rust color of an approaching sandstorm. I play with the gazelle, its black tail wagging like a dog’s as I tug on its horns.

“We have three kinds of this deer,” Mustapha says.

“This one is biggest?”

“Small.”

The wind increases, stirring the sand at my feet. Sheets of burlap toss in the air and twist away toward an obscured moon.

“Do you know we have Janjaweed in Chad?” Mustapha says. “I see them, know them. They leave their problems in Sudan. Their generals rob them. They get tired of fighting or join the Chad army for better pay.”

“Why would Chad let the Janjaweed come in?”

“The defense minister and minister of foreign affairs are both Arab. Deby says nothing so they don’t try a coup.”

“Why doesn’t he buy them off with oil money?”

“All the oil money goes to war; war with Sudan, for rebels, to generals protecting Deby. What do you think?”

“It makes sense.”

“Yes. Because none of it makes sense.”

Mustapha laughs. We shield our eyes against the wind, so much sand now in the air I cannot even see the compound walls. Then Mustapha disappears. The wind howls.

* * * *

In the morning, we wait for Izzy outside the library tent. We pass the time by visiting with a man chained to a tree. He is crazy from war, we are told. There are about fifty people in the camp like him. He lives on a moonscape of rocks and boulders, the skulls of animals. Children observe him at a distance. Dressed in red rags, his sister swings a metal pole and talks to herself. Warns us away.

Izzy finds us, excited that he just sold a goat. He tells us he called rebel commanders the night before. There is heavy fighting in Darfur, they told him. They were too far away to meet us. But he will call them again so I can speak to them on his Thuraya.

I want to see the border. Our UN driver takes us toward a water tower next to Wadi Hawar, which separates the camp from Sudan. He radios the dispatcher at the compound and gives our position. His voice shakes. I hear frantic talk from the dispatcher.

“What is he saying?”

“Don’t get killed,” Izzy says.

We park by rubber tubes connected to the water tank. Sparse shrubs thrive in the wet ground around the tubes, but beyond the tubes little else grows, except in the wadi where tall, grassy weeds wave above the water.

Across the wadi, we see Sudanese jeeps, machine-gun mounts and soldiers. A Sudanese soldier follows us with a telescope. Izzy points to a hill where he says rebels once camped. A soft wind ripples the water. Long-legged birds strut through the weeds.

“I lived in that direction,” Izzy says and points over the wadi, a short distance that is as far from here as the moon.

He calls Abdallaha Xaya Ahmad, a spokesman for the NRF, and interprets.

“The Sudan government is killing everyone. They are attacking us even now. Three days ago they bombed Umseeder village. Right now Umseeder is still smoking. Many killed. I don’t know how many. Yesterday, Janjaweed attacked people between the villages of Kutom and Disa and killed seventeen persons.

“At this moment all civilians can’t move between Kutom and Disa. Fasher University was attacked. Many students killed because they support rebels.”

Izzy hands me the phone.

“He wants to talk to you.”

I press the phone against my ear. I hear gunfire.

“What is your name?”

“Malcolm.”

“Malcolm,” he says struggling with his English, “we stay and defend our rights and people even if we are killed. What kind of name is Malcolm?”

“I don’t know,” I shout above the noise on the other end. “Scottish. My mother gave it to me.”

“Very nice to meet you, Mr. Malcolm. God’s blessing to your mother. Call anytime.”

Then nothing but the silence on the other end of the phone and the quiet breezes blowing over the wadi.

* * * *

When I lived in San Francisco and counseled Salvadoran and Cambodian refugees, I thought I learned from them the meaning of war and loss. But what I’ve seen here confounds my sense of earned expertise. Chad swirls around me, a seething waste of lost souls where years of war have shaken its steady heart, its proverbial moral compass—its way out.

Refugees live hopelessly in the camps. Government officials, aid workers, gendarmes, all of them alike are out for themselves because nothing and no one represents anything larger—especially American diplomatic globe-trotters who dance the dance of nonintrusive intervention, urging other countries to stand up against the war, knowing none of them will without US leadership.

I came here suspecting that oil companies were war profiteers, cynical oppressors of an already impoverished people—the obvious scapegoats, the villains. I don’t hold them blameless, but they may be the most honest among the dishonest. They arrived to find a moral vacuum, a willing bureaucracy that places more emphasis on titles and courtesy calls and the stamping of travel permits than governance and prefers personal gain to the protection of its own people.

While we were in the bush, President Deby accused Chevron and Malaysian state-owned Petronas of failing to pay taxes totalling $486.2 million. When Chevron produced official agreements, showing the amount they owed had been paid, Deby suspended the underlings who signed the documents and publicly denounced the taxes as mere “crumbs.” Chevron and Petronas, along with ExxonMobil, have already promised to invest $4.2 billion in an underground pipeline from landlocked Chad to the Atlantic port of Kribi in Cameroon, but that’s no longer enough. Now Deby wants another half billion dollars in taxes. Now he is demanding 60 percent of their profits. And what can even the petroleum giants do? If they refuse, Deby will boot them out, and another company will fill the void.

Long ago, oil executives must have discovered, as I have, that one’s position here determines rank and place in the pecking order of trickle-down payoffs. There’s no obvious way to fix it, only a way to work it. Because it’s not what you do but where you stand in line—and if you want to improve your standing, you have to do it by force. So strongmen set up shop and make their own rules and take what they can before the next coup. The American companies didn’t make these rules; they’re just willing to play by them in order to get the precious oil that you buy to fuel your car.

So acknowledge your own place in this order. Step in line. Be ready to change allegiances with chameleon speed. Play along and pray you don’t get trapped in the middle.

* * * *

The music drumming into my brain from Le Carnivore has improved little since Darren and I were here three weeks ago. The sound system has been repaired. A few US oil workers sit in folding chairs. One of them apologizes to a waitress for his behavior the previous night.

“You’re back,” Princess says.

We offer her a seat but she demurs. She wears a pink blouse, tight jeans, and impossibly high platform shoes. She sits alone until a man kneels behind her and puts his hands over her face. She grins and turns around.

With luck, he will carry her away to England where she can become the soccer player of her dreams. With luck, he will offer her more than ten dollars afterward. As someone who sits here pleasantly plastered after too much time in the bush, knowing that I will fly out to Paris in a day, I can indulge in optimism.

Just an hour earlier we had taken a cab to the airport to check our luggage. A sticker on the windshield read, usama bin laden. mai gaskiya yana tare da allah. “Osama bin Laden. Praise be to God.” Darren tipped the driver a dollar and the man smiled and pumped Darren’s hands with both of his.

“That’s how we defeat terrorism,” Darren said. “One goddamn US dollar at a time.”

I gave the driver a dollar too. Just for backup.

Princess and her escort get up together. She pauses at our table, holding his hand.

“How was your trip?” she asks.

“The fighting continues.”

“Yes.”

Princess and her man walk away to pursue their tryst in the alley, a pickup, some rotten hotel room. She doesn’t give us so much as a backward glance. Soon, Darren and I will do the same, put the whole lot of it behind us. The music, the oil workers, the hovels of refugee camps, the killing. All of it. Let it be gone with the daybreak, gone with the rains. What else can we do but wish it away?

There is no promise, Mustapha. You got that right.