- The aftermath of the Mosul chow hall bombing, December 21, 2004 (Dean Hoffmeyer, Richmond Times-Dispatch / AP Photo).

On an otherwise typical, sun-parched afternoon at Forward Operating Base (FOB) Marez in Mosul, Iraq, four days before Christmas 2004, someone walked unnoticed into the chow hall and blew himself up near the sandwich bar. The blast ripped a hole through the roof forty feet overhead and tore apart fifteen US soldiers and seven civilian contractors—along with the bomber.

No one knows for sure how he gained access to the chow hall or how he delivered his lethal payload, but among the soldiers, shock has mixed with standard-issue paranoia to produce a host of conspiracy theories. Some credit the attack to a faceless mess worker with jihadi sympathies, perhaps a Tamil Tiger in hiding. He could have planted the bomb in the cabinets below the sandwich bar, and then used a remote detonator. He could have saved his own skin. Another theory attributes the explosion to a surface-to-ground missile launched with precision target-acquisition equipment from somewhere along the jagged line of beige rooftops deep in the heart of Mosul. After all, the complete layout of the base, including the location of the chow hall complex and its GPS coordinates—slightly skewed per US military security requests—was freely available to local mujahideen via Google Earth.

The official story, however, blames Ahmed Said Ahmed al-Ghamdi, a twenty-year-old medical student, who had grown up in Sudan, where his father was a Saudi diplomat. He could have entered the base through one of the many holes in the miles-long, barely protected perimeter, then sneaked into the chow hall with a stolen Iraqi Civil Defense Corps uniform and ID card. He would have been surprised, perhaps even worried, by how easy it was. Then he would have sized up the scene before him (soldiers and Iraqis dining together in clusters throughout the football field–size cafeteria), planted his feet in the spot with the densest mass of people, and closed his eyes. He would have detonated a suicide vest laden with several pounds of C‑4 or Composition B and pounds more of ball bearings, and he would have vanished instantly into a fine red mist.

I was in the middle of checking my e‑mail at a FOB internet facility, thirty miles south of Mosul, when the lines suddenly went dead. Ten months into my tour, I was waiting out redeployment at a boring oasis called Q‑West. While Third Platoon spent their days running around the city with infantry units from the spanking new Stryker Brigades, most of Charlie Company—including my platoon—was stuck biding time at “Key West”—as it was euphemistically known. “Commo blackout,” the administrator announced from the doorway. That’s when I knew: someone in my brigade had been killed—they always suspend communication for a couple of days to give the Mortuary Affairs people enough time to notify the families before sympathetic e‑mails start rolling in.

When I got back to the company area, the squad leaders were herding everyone down to the Tactical Operations Center. It was there the CO told us that two of our friends, two of our “battle buddies,” Specialists Nicholas Mason and David Ruhren, were dead. Others were badly injured, no telling how many yet; he’d let us know. The CO had tears in his eyes. Somehow he’d managed to make it this far into our tour without a major casualty, and then, as we were preparing to turn our gear and our mission over to our replacements, the worst occurred. He didn’t offer a speech or any consolation. There wasn’t anything to say. Ruhren and Mason didn’t die gloriously. They weren’t holding their positions to the end or rushing in under fire to pull out wounded comrades. They were making sandwiches. Nick Mason, his friends remember, was piling the salami high and stuffing his pockets. And, as he turned for the door, you can bet he was smiling.

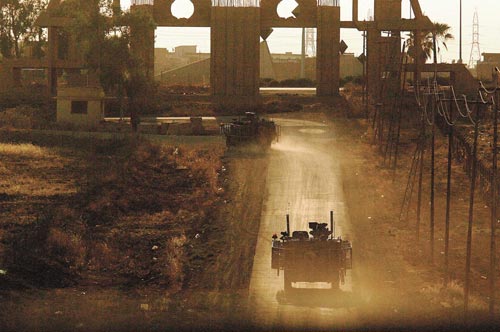

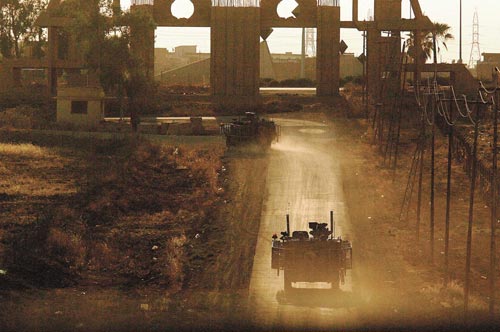

- Soldiers leave FOB Marez in a Stryker combat vehicle to conduct a cordon and knock patrol (Air Force Tech. Sgt. Jeremy T. Lock / Defense Department photo).

We had arrived together months earlier, stepping off the C-130 into the chilly March air of the Tigris basin, greeted by Mosul’s sulfuric stench. We were the 276th Engineering Battalion, tasked with minesweeping, convoy escort, and security fence construction. It was late at night, and we’d been flying for hours, but the captain—or colonel, who could tell in the darkness?—had us line up in a company formation even though he knew one mortar could knock out half of the unit.

Things were different then.

It was the tail end of year one. Humvees had only jury-rigged armor, if they had any at all. We wore beige-and-brown desert camouflage uniforms with conspicuously green body armor. We spent our first days scavenging scrap metal, taking advantage of the odd-job welders and professional metalworkers in the unit to outfit our scrappy array of “guntrucks”—embarrassing, Vietnam-vintage five-ton dump trucks retrofitted with machine-gun mounts and painted olive drab.

In the beginning it was all good fun: volleyball, weight lifting, webcams, video games, and thousands-deep DVD libraries. In the mornings, we ate eggs made-to-order, fresh bacon and sausage, cereal, juice, and fresh fruit, all served by a swarm of Sri Lankans and Filipinos whose smiles were like so many Polynesian leis. Friday night, we gorged on steaks, crab legs, and near-beer.

Then, about a week after we arrived, a hail of orange and red tracers streaked back and forth across the black sky. The West Virginia National Guard unit we were replacing had come in with the invasion, but this was the first firefight they’d seen. During their yearlong tour, they hadn’t taken a single casualty and had never so much as laid eyes on an IED. They’d grown accustomed to cool, quiet nights interrupted only by the low hum of generators and the crunch of gravel underfoot.

Things would change during year two. I would change, too.

Before leaving the States, I had made out a will designating my mother as sole recipient of my $250,000 Army life insurance policy. Should my mother have died, the premium was to be divided between my two sisters—except for the $15,000 that I set aside for my girlfriend, Joanna, my childhood sweetheart, whom I came very close to marrying in the predeployment hysteria. I wanted her to have a nice vacation to forget about me if I got killed. I was twenty-three years old. It was hard not to get caught up in the romance of it all.

But we didn’t board a troop train and kiss our wives and girlfriends goodbye through the windows as the engine pulled away. Our departure was less emotional, more sterile. We boarded a charter bus for the two-mile ride from Fort Dix to McGuire Air Force Base. We loaded our gear onto pallets and boarded a cargo flight to Morón, Spain. We flew from Spain to Kuwait, where we spent two weeks baking in the desert, then from Kuwait to Mosul. I don’t identify a whole lot with the young man who made that triple-legged flight in March 2004. But I don’t think I’ll ever be able to distance myself from the man I became over the twelve months that followed. It wasn’t sudden or dramatic; somehow the slow, plodding tread of the war just marched deep inside of me to a place that I do not know how to reach on my own.

The rhythm of it calls me back, all through the day, every day. And I wonder if I’ll ever be able to leave it behind. Everything pales next to Iraq. Where else will I ever feel again that strange mix of dire, mortal seriousness and boyish innocence? Where else will I pit scorpions against geckos in miniature cage matches? Where else will I pull a tarp over a pile of corpses scavenged by dogs in the night? Three and a half years later, I’m still trying to sort it all out—still trying to figure out how the hell I wound up scanning the plains of Saladin’s Nineveh; watching over confused, frightened, and understandably pissed-off detainees; staring down the barrel of my rifle at children. In twelve months, I never fired a shot. Most days I’m happy about that, others I feel like I got ripped off, left with a severe case of combat blue-balls. I have to remind myself that I am here, among the living, the lucky—and to be thankful for that. But I feel a twinge of regret, like I’m a fraud for calling myself a veteran without ever having been deep in the shit; and I harbor a strange nostalgia for those days, as if my life had more meaning when it was ever more tentatively mine.

I have wondered since leaving the National Guard in July 2007, at the end of my six-year contract, if the other guys from my unit are as consumed by their memories and frustrations as I am, if they, too, feel something less than fully alive in the civilian world we now inhabit. I have wondered, more than anything else, how the small handful of troops from Charlie Company who saw the worst of it in the chow hall that day have fared since our return.

If I could somehow gather their stories, pull together the common threads, maybe I could start to understand my own story.

* * *

Staff Sergeant William A. Rossin—or SSG WAR, as his Virginia Purple Heart license plates read—places most of the blame on himself. David Ruhren, on his way to the chow hall that December afternoon in Mosul, stopped by Rossin’s living container to invite him along for the walk. The Marez mess was about a mile away from C Company’s quarters, up a hill to the west on the opposite end of the sprawling FOB. Rossin declined Ruhren’s invitation. He’ll never forgive himself.

When I show up at Rossin’s house in Chesapeake, Virginia, I find him in the backyard standing on a milk crate, shooting stacked quarters with his pistol. “I never had a gun before I went to Iraq,” he tells me. “Now I have a whole damn armory.” His eyes are ice blue and piercing from under the low-slung brim of his Twenty-fifth Infantry Division ball cap, but his speech is deliberate and soft, leveled-out by psychotropic medication. With the help of the drugs, he no longer patrols the perimeter of his home at night and has stopped tearing through the kitchen cabinets looking for IEDs, but he continues to amass weapons—dozens of WWII-issue rifles, all of them loaded, and an antique .45 automatic that never leaves his side. They’re his protection, his peace of mind. Rossin sees David Ruhren’s ghost often, a shadow in the woods while he’s walking his dog, a fleeting face amid crowds.

Rossin joined the National Guard after a two-decade break in service, partly in response to 9/11, but more as a way to prove to himself that he, then sliding toward fifty, wasn’t “too old to make a difference.” Some midlife crises come as shiny red sports cars; Rossin’s came as a new pair of combat boots. He signed a “try one” contract—a special one-year program for prior service veterans—and expected to serve out his stint as a weekend warrior, drilling once a month at C Company’s armory in West Point, Virginia. “Well, Elliott,” Rossin says, “there have been a few unforeseen things.” Rossin had served only a handful of drills when he and the rest of the company received mobilization orders.

On January 5, 2004, Charlie Company commenced intensive predeployment training at Fort Dix. Days began at 0330 and ended around midnight. Rossin had a hard time readjusting to army life. New SOPs and updated weapon systems presented less of a hurdle than long hours under a heavy load, subzero temperatures in New Jersey’s frozen Pine Barrens, and the difficulty of taking orders from men half his age. He also had a hard time affecting the hard-ass attitude expected of him as squad leader. His troops were his son’s age, and he was inclined to treat them like sons. When he refused to smoke a junior soldier for showing up late to formation, a younger noncom laughed: “Bill, that’s the grandpa in you.” From the first day of predeployment training, David Ruhren stepped in to offer the platoon grandpa a hand, carrying some of his gear and helping him disassemble and reassemble his weapon—and soon other junior soldiers, like Nick Mason, followed Ruhren’s lead.

“They never made fun of me or made me feel like I was too slow or too weak,” he says. We are safely inside his house now, and Rossin teeters gently in his high-backed rocker; but the shutters are closed against outside light, and he keeps his pistol tucked in the holster on his hip. “I couldn’t have done it without them.” Rossin tried to thank David for helping him, but Ruhren wouldn’t have it. “No way, man. That’s what battle buddies are for.”

In Iraq, David continued to look out for Bill and always kept the mood light. Rossin recalled fondly how Ruhren nicknamed his .50 caliber machine gun Sarah. Bluesmen have their guitars; grunts have their weapons, and for Ruhren, Sarah was a trusted friend. When he returned home for a two-week leave in November 2004, Ruhren feared that Sarah would malfunction under another soldier’s watch. He told his mother, Sonja, that he had to get back; he was afraid his friends would run into trouble without him. He was right.

The Second Battle of Fallujah drove insurgents north to Mosul, where, in late November 2004, Third Platoon proved its mettle in defense of a series of bridges across the Tigris River. The platoon’s soldiers won several Purple Hearts and a Bronze Star—owing to Sarah’s flawless performance against an insurgent mortar team. When he eventually rejoined his platoon, Ruhren’s buddies joked that Sarah had fallen for another man. Kidding aside, Third Platoon vets will tell you: it’s a miracle that no one died on “the bridge”—the shorthand the platoon still uses for the place where Bill Rossin won his Purple Heart and earned his nightmares.

Soon after, Rossin started to suffer tremors. He would wake up in the night, sweating and shaking. Daily mortar attacks and the stress of leading troops on mission after mission proved too much for him, physically and psychologically, so the platoon commander arranged to put his master-electrician skills to use wherever the Army needed them. Rossin traveled by helicopter to FOBs as far south as Baghdad to repair generators and HVAC systems damaged by mortars, misuse, and the scorching, dusty heat. But he was back at FOB Marez with Ruhren, where all seemed to be returning to normal, as the days sped toward Christmas and the end of his deployment.

David’s death drove Bill over the edge: “When we lost him,” he tells me, his eyes drifting to the floor, “it was like losing a son.”

When Rossin returned to work in May 2005, Dominion Virginia Power threw him a welcome home party to express gratitude on behalf of the company and all employees. Dominion had paid the difference between Rossin’s Army salary and his electrician’s salary as part of their Support the Troops policy. The supplementary wages allowed Rossin to continue accruing retirement and kept his benefits active during his absence.

But a few months after returning to work, Rossin’s post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) began to manifest itself on the job. He was terrified while driving home after night shifts and eventually requested a day-shift-only schedule. He began making reckless errors while repairing high-voltage equipment, putting other employees and himself at risk. Loud noises at the plant triggered flashbacks and hallucinations, often embarrassing Rossin so badly that he would have to leave work. He expected full support from Dominion’s military-friendly HR department. Instead, he found himself out of a job.

The Servicemembers Civil Relief Act (SCRA) protects reservists’ full-time civilian jobs while they are deployed, guaranteeing reemployment with identical or improved position and pay, but SCRA does not require companies to keep wounded veterans employed when their injuries interfere with the performance of their jobs. Nor does SCRA require companies to extend benefits to veterans who are laid off due to physical or psychological injuries.

And so Rossin was forced to apply for full disability from the Department of Veterans Affairs. He will be eligible to collect early retirement in two years, at fifty-five, or he can wait until sixty-five to collect full retirement. If he seeks employment, he will have to forfeit a percentage of the VA disability on which he depends. Though he desperately wants to return to work—being unemployed has, he feels, robbed him of his identity—he fears that work-related stress could trigger his PTSD. That’s not a risk he is willing to take.

Rossin’s wife, Jennifer, suffers too. She has slept beside her restless husband for the past three years, woken up with him when he sees David Ruhren’s ghost in his dreams and lurches out of bed. She has watched Bill amass weapons and given in to his need to protect himself at all times. Jennifer is there when Bill’s anxiety gets the best of him in public. She knows his limits and she carefully monitors his mood.

Jennifer, who has an accounting degree and works as a CPA, has become the family breadwinner. The firm’s office is only a few miles from the Rossin’s home, and Jennifer leaves work frequently to deal with Bill’s breakdowns.

“Do any of your clients have a problem with your unreliable schedule?” I ask.

“If they do,” she replies, “they can find another CPA.”

She always warns her clients, “My husband comes first.”

But Bill’s need for constant care has created a considerable strain on his marriage. He and Jennifer have discussed separation. They were kicked out of group marriage counseling at the Hampton VA because, as Bill remembers, “I had a violent outburst.” Until recently, such group counseling was the only VA resource available for couples dealing with war-induced marital stressors, but now Bill and Jennifer are seeing a private counselor whose office benefits from a VA grant.

Both Bill and Jennifer believe that recovery is possible, but Bill’s private arsenal grows—and their medicine cabinet swells with antidepressants and sedatives. And even with all the medication, Rossin is tortured by the thought that he could have somehow delayed soft-spoken twenty-year-old David Ruhren for a few vital minutes, even seconds, which might have saved his life. “I could’ve done or said so many things that would’ve just held them . . . Thirty seconds maybe. And it could’ve made all the difference between them living and not living.” Each time Rossin says, “I could’ve done or said so many things,” it’s the same—his voice falters and then gathers speed when he says “thirty seconds maybe”; his head hangs on “living” and rises on “not living,” his eyes gazing absently past the person he’s speaking to. The lament is neither staged nor affected. It’s habitual, rhythmic: it is the broken record playing inside of Rossin’s head, the soundtrack to the moments he can’t stop reliving.

Bill Rossin passed on David Ruhren’s invitation to walk with him to chow, so Bill was not in the mess hall when the bomb detonated. He was not there when the medics carried his buddies, these boys he thought of as sons, out on stretchers. He wasn’t there when David died. But he was there when the platoon loaded David’s body—and Nick’s body and a dozen others—into the rear hatch of a C-130 cargo plane. Bill Rossin is still there.

* * *

The air around Mosul—chilled overnight by cool mountain breezes rolling south from Kurdistan—had warmed by lunchtime on December 21, 2004. It was shaping up to be a cloudless, near-perfect winter day when David Ruhren came to collect Richard Hursh for chow. They stopped by Bill Rossin’s container to try to talk him into joining them, but Rossin begged off. So the two strolled to the motor pool, where they met up with Nick Mason, who had the Humvee idling and was already halfway through his routine maintenance checks. Nick was especially attentive that day, because he was preparing to drive that rickety old Humvee on a special mission, across the Tigris to a defensive position at the edge of yet another bridge, where Third Platoon would spend a teeth-rattling night warding off insurgents. On the way to the chow hall, the three soldiers took the Humvee through a section of old bunkers and trench roads in an abandoned part of FOB Marez, testing the shocks, double-checking the transmission. Mason and Hursh were in a great mood—that night, they’d operate as a driver-and-gunner team for the first time in nearly ten months.

After they finished eating, Hursh, Mason, and Ruhren slipped over to the sandwich bar, piling their bread with meat and stuffing their pockets. “Mission food,” they called it; if they were going to defend a bridge, they first had to defend themselves against MREs. They said goodbye to a table full of lingering platoon mates and headed toward the door.

“We walked into it,” Hursh remembers as we talk over the phone. He’s on lunch break from work, but his voice is steady and unhurried. “I remember seeing the blast, seeing the hole in the roof. I thought a mortar had dropped in or something.” The explosion threw Hursh back about twenty feet, knocking him senseless below the neck. “I kept telling my body to get up,” he says, “but it wasn’t going anywhere.” The first person to reach his side, a middle-aged female soldier, broke down crying. Then a civilian and a Twenty-fifth Infantry Division soldier began assessing and treating Hursh’s wounds, loading him on a stretcher and carrying him to the casualty collection point. “I kept trying to look around,” Hursh recalls, “but I couldn’t move my head.” Loaded onto the back of a truck, rushing across the road to the trauma center at an airbase called FOB Diamondback, Hursh slipped in and out of consciousness. Tasting blood in his mouth, he worried that he might be dying.

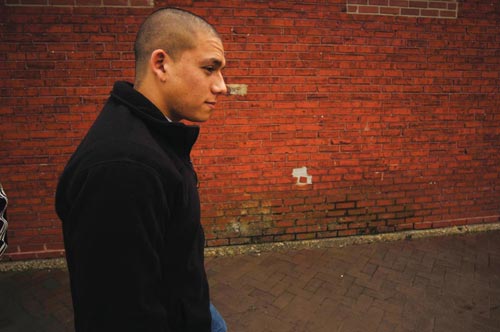

- Richard Hursh on a stretcher after the bombing (Dean Hoffmeyer, Richmond Times-Dispatch / AP Photo).

Shrapnel had shattered Hursh’s scapula and broken his arm, and small pieces had ruptured membranes in his lungs, causing a condition known as bilateral hemothorax—Hursh was drowning in his own blood.

“Was it chaos?” I ask, “Or did the trauma specialists seem to know what they were doing?”

“To me it was chaos,” Hursh replies. “But everyone else was on point. I could hear guys yelling and screaming all around me, but the medics were on it.”

Especially astute was the trauma physician at Diamondback, who noticed that Hursh’s O2 saturation levels were so low that morphine might kill him. Hursh had his chest cut open and a chest tube inserted—sans anesthetic. It was at Diamondback that an OR tech told Hursh that he’d lost his thumb, or rather that it had been amputated several minutes prior. “I really didn’t care,” he says. “I heard him, but I didn’t realize it was gone.”

He had an even harder time believing the news about his friends. “Somebody came over and told me that they didn’t make it,” he remembers. “Of course in my mind, that wasn’t true. So everywhere we went, every time we stopped, I checked with whoever was treating me, ‘Hey, do you have the status of Mason and Ruhren?’ And they’d go, ‘We don’t have anything right now.’ And you could tell . . . They must have had the casualty report, because you could see it in their eyes, and they’d be like, ‘Oh, they’re not on the list right now . . . but . . . as soon as they come in we’ll give you an update.’ And you could tell they were lying.”

The Army rushed Hursh to Balad for emergency surgery, where he got another chest tube—this time, thankfully, under general anesthesia. Hursh spent a couple of days at Landstuhl Regional Medical Center, Germany, and on Christmas day, he arrived to a tray full of special Christmas treats at Walter Reed. “It was a nice gesture, but unfortunately I wasn’t allowed to eat anything.”

On his first day back in the States, he pulled aside a nurse. “I just got here,” he explained, “but I’m one of the later guys. I’m just wondering if two of my friends got here yet?” Hursh pauses. “Of course, they weren’t there,” he says, “but I had to ask anyways.”

He also couldn’t believe at first that part of his hand was gone, especially when his supposedly amputated thumb began to throb. “I had a cast all around my arm, and my hand was really swollen. I told the nurse, ‘My thumb’s jammed up in this cast.’ She said, ‘You don’t have one.’ I had to have the doctor come and cut off the cast. I didn’t believe her.” It took several months of surgeries and occupational therapy before Hursh regained use of his arm, and he’s still learning to get by without a thumb. “It’s little things,” he says. “At first I couldn’t tie my shoes. Now I’ve learned how to do that.”

But Hursh insists that the hardest part of his recovery has been “just not having those guys around.”

Richard Hursh is built like a bulldog. He’s short, broad-shouldered, and square all around, with tan skin and jet-black hair that don’t match his Germanic name. He looks like an ex–football player, still solid as a rock but too small for the college game. When I meet up with him outside his apartment in Norfolk, he looks more like a prepped-out frat kid than a hardened Mosul vet. Sporting cargo shorts and a gray polo shirt, to go with a shy smile under cautious brown eyes, he could be waiting for an Abercrombie & Fitch photographer. Juggling my bag, I approach him with my hand extended, suddenly worried about an awkward, thumbless grip, but his remaining fingers squeeze my palm without hesitation.

Inside, Hursh’s apartment looks much the same as any other twenty-something’s bachelor pad. Save for a few NFL posters on the beat-up walls, Hursh and his roommates have spared interior decoration in favor of a room-devouring entertainment center. Drawn shades block out the early afternoon sun. An unshaven roommate lounges on a mildewed couch. Hursh’s bedroom, however, seems extracted from a different house altogether. The soldier’s fastidiousness is evident everywhere—bed made, shoes arranged neatly on the floor, desktop clear with books straightened on the shelves above.

On the wall beside his desk, there is a poster detailing the mechanical and electrical structure of the UH-60 Black Hawk, the Army helicopter that Hursh still hopes to fly—but he admits that his “hope is diminishing.” He has visited an Army and a Coast Guard flight simulator and found both to be impossible to operate without a thumb. Hursh is trying to get a rigid thumb post that he could manipulate with the muscles in his palm, something less pretty than the cosmetic prosthesis he has now but more stable and dexterous.

If he can’t fly, Hursh wants to be a weapons designer. But he doesn’t want to work on small arms design or advanced weapon systems. He is interested in developing body armor, vehicular armor, helmets, and personal tactical equipment. He wants an engineering job that will allow him, as he says, “to do in my civilian career what I can’t do in my military career”—namely to “build something, design something, test something that will help the troops on the ground, save lives, make it easier.”

Hursh grew up in a military household, the son of a command sergeant major. “I think I joined up,” he recalls, “just because I was in a military family. I enjoyed the military lifestyle, I planned to make a career out of it. I thought that it would be exciting, and it was a good way to go to college, too.” Hursh had another motivation: he signed his enlistment papers just ten days after September 11, 2001. He was a junior in high school, and much of the kid remained when he deployed to Iraq two and a half years later.

Drilling with the 229th Engineer Battalion in Fredericksburg, Hursh quickly befriended another young soldier fresh from Basic, a quirky blond kid with a very high PT (physical training) score and a bizarre affection for duct tape. Nick Mason and Richard Hursh were the same age, eighteen, and they were similarly motivated; both had joined partially for college benefits but mostly out of patriotism. Their friendship accelerated with the mobilization call. They learned to depend on each other as soldiers and friends at Fort Dix, and in Iraq they would trust each other like brothers.

“What made him unique was that he was so outgoing,” Hursh tells me. Mason never sat still and never stopped smiling; he refused to give in to the Iraqi heat or the FOB malaise, and his energy was infectious. “He always wanted to be doing something,” Hursh recalls with a laugh. “Even if I was like, ‘Man, I got an hour, I’m gonna crash out,’ he’d always be in my room, usually covered in dirt, jumping on my bed . . . like, ‘Hey, let’s do something!’ I don’t remember him sleeping.”

In King George, Virginia, half a dozen telephone poles owe their nicks and dents to the bumper of Nick Mason’s pickup. Nick’s passion for “mudding” cost the town so many telephone poles, in fact, that its citizens gave him a nickname: Paul Bunyan. In the Iraqi countryside, where there are no trees and few roads, Mason found himself charged with a Humvee in an off-roading paradise. Nick’s parents were amused and a little disturbed to learn that their son had been deemed the platoon’s best driver.

Despite the threat of military discipline, Mason’s antics continued in Iraq—and he found a ready accomplice in Richard Hursh. Hursh remembers tooling around the FOB in the passenger seat while Mason put the platoon’s Humvee and five-ton to the test, sometimes practicing drive-by attacks with a slingshot, but more often clinging for dear life. “We took the five-ton out after it rained,” Hursh remembers. “You know the mud there was terrible. And he just slammed on the gas, went through these huge mudholes. The goal was to get the mud from the front to fly all the way over the cab and into the dump truck. It was hilarious at the time, until we pulled back into the motor pool.” As usual, Mason’s smile kept them out of trouble.

Hursh and Mason had planned to transfer their passion for things motorized from four wheels to two. While other soldiers daydreamed of long vacations, sex, sleep, and booze, Hursh and Mason spent hours poring over motorcycle magazines. They dreamed of riding together in the annual Rolling Thunder Motorcycle Rally. They sneaked away from Fort Dix in the weeks before they deployed to purchase motorcycle jackets at a mall in Trenton. And David Ruhren hoped to join them; while in Iraq, he’d even purchased a vintage Harley chopper to ride in the parade. Of the three friends, Hursh is the only one who survived to see the dream through.

* * *

Early on a Saturday morning in late May, I arrive at the Mason’s home, expecting to find Nick’s family sipping coffee, finishing breakfast. But they’ve been up for several hours already, and they have company; Vic, Christine, and Carley—Nick’s father, mother, and sister—are chatting in the driveway with Christine’s brother Dieter and another friend, leaning on tailgates, cold Budweisers in hand. Dieter has just finished unloading a pile of picnic tables and benches—tomorrow, the Masons will ride in Rolling Thunder for the third year in a row, and they’ll have a big barbecue afterward. For the third year running, Carley will ride behind Richard Hursh, in place of her brother. Dieter grips my hand, introduces himself with a ruddy smile. Dappled May sun drips through the trees, a warm breeze carries the damp smell of the woods. I barely know these people, but I feel at home in their presence.

I’ve met the Mason family several times, though I never knew them while Nick was living. I vividly remember Christine Mason’s speech at the memorial service held for Nick and David upon our return to the armory in West Point, Virginia. She extolled the virtue of American soldiers and challenged us to keep the faith. She broke down and cried at the podium, leaning on Carley and Sonja Ruhren for support. It had only been seven weeks since Nick and David were killed. As the three women embraced each other, nearly collapsing in a triangle of tears, a photographer moved in to capture the misery. Vic lunged for him, and it took a squad of soldiers to hold him back. Vic still wishes they hadn’t.

Vic Mason looks like a former drill sergeant—compact, thick muscled, lean and mean, obviously sharp as a tack. His head is shaved to the skin and he wears a typically southern, close-cut goatee. Like his son, he has trouble keeping a smile from wrinkling the corners of eyes, dimpling his cheeks. Talking to Vic, watching his face, I see the man that Nick would have become.

Unlike Nick, Vic doesn’t have a shred of the soldier in him; though deeply patriotic, Vic never joined the military. Too young for Vietnam, he chose a civilian track instead, eventually following in his father’s footsteps as the King George county clerk. He has the comfortable air of a man well accustomed to dealing with all types of people in all types of situations, from criminals awaiting arraignment to state politicians. In his office at the county courthouse, he answers the phone warmly, pushes his steel-rimmed glasses down on his nose, exudes confidence and control. It’s only when he talks about Nick that the cracks show, and even then only slightly—and never in the presence of strangers.

Christine Mason doesn’t hold it together quite as well. Christine is wearing an Army National Guard T-;shirt and several pairs of Nick’s dog tags. A cluster of black ID bracelets bearing her son’s name stretches halfway up to her elbow. The Mason house is filled with his belongings and photographs. They have preserved Nick’s room exactly as it was when he deployed. And when their son’s body arrived in Virginia in early 2005, Vic and Christine decided to bury Nick at home. Friends, neighbors, and perfect strangers came in droves to help clear an acre of forest behind their home where Nick’s memorial now stands.

They erected a granite headstone laser-etched with a photo of Nick standing on the bumper of his five-ton outside of Mosul, beaming—rifle in hand, fist raised, the image of an American flag waving behind him. And built behind Nick’s grave is a huge granite castle, the emblem of the Army Corps of Engineers. The Masons pass hours sitting on the benches here, just to spend time with him. They tend the gardens around the memorial, clear brush from the brick walkways; they make sure there is always a full bottle of Maker’s Mark for any of his buddies who want to come to drink with him.

Tears well in Christine’s eyes as she tells me all of this. “I look out my bathroom window every day,” she says, “just waiting for him to walk up the trail and tell me, ‘Sorry, Mom. Sorry I had to do this to you, but I’m back now.’ I still wait for him to come back.”

She gives me a hug, Nick’s dog tags clinking together against my chest. It’s a desperate, sincere hug. She is reaching through me, a living link, trying to feel her son—I knew him over there, as a soldier, and I’ve seen him more recently than she.

Nick Mason used his two-week leave to visit Christine’s relatives in Germany, something his mother always wished he’d be able to do. Vic and Christine never visited Nick at Fort Dix. He’d told them not to come; saying goodbye once was hard enough, and Nick didn’t think he could handle doing it again. So the last time they saw their son was the day they dropped him off at the armory in West Point. It was January 5, 2004, and when they waved goodbye as Nick’s bus pulled out onto King William Avenue, heading toward the paper factory, toward I-64 and I-95, toward Iraq, they couldn’t have known.

They were so proud.

In the lobby of the Steigenberger Hotel in Frankfurt, in October 2004, Nick ran into Brigadier General Al Smith, whom he recognized from a Virginia National Guard ceremony the previous year. The young specialist introduced himself to the retired general. “It became quite apparent to me that this Nick Mason was an unabashedly friendly, confident, self-assured, gregarious guy,” Smith wrote in a letter to the Fredericksburg Free Lance–Star. “[He] knew who he was and where he was going, and [he] was proud to be an American.” Nick and the general chatted over a few Bitburger pilsners, covering “the gamut of topics ranging from the Red Sox winning the pennant to who would win the Super Bowl, whether or not President Bush would be re-elected, the problems with media bias in reporting the war, how he looked forward to rejoining his volunteer fire department buddies, hunting, fishing, working on cars, and seeing his mom and dad and sis again.” But what impressed General Smith most of all was Nick’s confidence: “Never once did he say he was afraid or that he wished he weren’t there. He talked about his pride as an American soldier and how lucky he was to be part of a historic moment in history when America was bringing freedom to the people in that part of the world.” Vic and Christine cherish the general’s letter, taking small comfort from the knowledge that their son was a model soldier, a model American.

Nick had been making his parents proud for a long time—in high school, he served as a volunteer firefighter, won regional wrestling tournaments, saved his grass-cutting money to buy his first truck. He made his parents laugh: fashioning his prom tuxedo out of duct tape, zipping his go-kart around the yard, getting his truck stuck in the mud under the power lines behind the house, burying himself to his neck in mud trying to get it out. He made the whole town smile, and he smiled with them. When he died, the King George Fire Department used its hook-and-ladder trucks to suspend a giant American flag above the entrance to the high-school gymnasium, where a standing-room-only crowd lit candles and shared stories about their native son, their friend, the quirky blond kid whose truck couldn’t stay away from telephone poles. Nick’s former classmates decorated the trees around his grave with dozens of duct tape bows.

* * *

It wasn’t easy to find Sonja Ruhren. Her number is unlisted. When I called the restaurant she started, Davey Boy’s Cafe, the line was disconnected. Davey Boy’s, I later learned, had failed within the first year. I finally coaxed Sonja’s number from Vic Mason and had to leave several messages before she returned my call. Sonja is understandably reluctant; she feels hounded by reporters stalking her at the gas station, the grocery store, even at her home—a little house on Lake Arrowhead, near Stafford, Virginia, that she purchased just before David deployed.

It’s foggy and cold when I arrive, and Sonja ushers me inside. Her bay windows overlook the lake and a wide backyard. Through the screen door, David’s dog—a ragged old chow—lunges at me with teeth bared, barking furiously. Sonja would have gotten rid of him after David died, but he reminds her of her son. He also protects her, now that David’s gone.

In the living room, vanilla-scented candles mask the cigarette smoke that hangs visibly in the air. Sonja has a quick, raspy laugh, but her smile retreats as suddenly as it comes, betraying a face that hasn’t known happiness in almost five years. Standing an even five feet, she’s kept the figure of a twenty-year-old. She knows it, too—and she knows that she wouldn’t have any trouble finding a companion if she were interested. But Sonja doesn’t think she’ll be able to rejoin the land of the living. Her son’s death was, in so many ways, her own death. The house by the lake is home to a pair of ghosts—a mother’s and a son’s.

David didn’t live in the new house long enough to fill all of the nooks and crannies. There is no jumble of long-retired toys in his closet, no mess cluttering his desk. Still, his mother has managed to transform her home into a shrine. Shelves are loaded with dozens of portraits of David, from all stages of his life: a goofy kid clutching an armful of gifts beneath the Christmas tree, grinning ear to ear; a handsome teenager posing with his prom date; the basic-training photo, chin up, jaw set. David’s uniforms are displayed in huge shadow-boxes on the basement walls. David’s chopper, painted with the insignias of the 229th and 276th Engineer Battalions, sits proudly under a spotlight. His medals and citations fill a backlit display case. On the top shelf, folded into a triangle, encased in wood and glass, rests the American flag presented to Sonja at David’s funeral.

There’s a picture of David’s castle—an exact replica of the Engineer castle Nick Mason’s family built beside their son’s grave. Sonja liked the memorial so much that she asked the Masons for the blueprints, then built “Davey’s castle” behind her mountain cabin in western Virginia. Sonja wants David to have everything, even in death. But Sonja feels her son, buried in the cemetery at Quantico, has been left exposed and alone. “David is not sheltered the way Nick is,” she says. Sonja believes that Nick rests in peace on his family’s property, while her son is unprotected, constantly tormented by sick people who steal the flowers and rosaries that well-wishers leave for him. She also sees the glorification of her son’s death as just another form of exploitation. Photographers especially like to get pictures of her crying in public. “A lot of times the Masons and I will be at the same event,” she tells me, “but it’s always me who gets in the newspaper.” She knows that a tearful single mom who has lost her only son makes good copy.

She doubts that any one of the many people who have memorialized David in news stories, speeches, or public ceremonies have any interest in the actual person behind the uniform. “They don’t know my son,” Sonja insists. “They don’t know Davey.” And yet they’ve made a martyr of him. David has been anonymized, transformed into Sergeant Ruhren, soldier and hero, someone Sonja claims not to know. She worries that the myth of David Ruhren will overtake the man, and she’d forgo any memorials or tributes rather than have David misrepresented, especially if his story compels other young men to volunteer.

The news stories also have prompted more than one young woman to come forward claiming to have given birth to David’s child in hopes of sharing his survivor benefits. One girl went as far as to schedule a paternity test for her infant. Sonja suspected a hoax from the start, but propelled by the hope that there might be some living connection to her dead son, some piece of David out there, she met with the woman. “My son dated model material,” Sonja says, “I took one look at this girl and I knew something was wrong.” Confirming her suspicions, the woman disappeared a few days before the test and never contacted Sonja again. According to Sonja’s casualty officer—the military liaison in charge of scheduling funerals, counseling families, and disbursing life insurance payments—her encounter with the con artist was not exceptional.

“People think he still owes them something,” Sonja says, “as if he hasn’t already done enough.”

She can’t find comfort in platitudes like “Thank you for your sacrifice” and “God bless you.” She knows that people have good intentions, but she can’t brook their ignorance. When people around town run into her, they “walk on eggshells,” they “always feel like they have to say something.” Sonja just wants to be left alone. “Thank you for your sacrifice,” she mutters, visibly annoyed. “I always tell them, I didn’t sacrifice anything. You want to thank someone, go visit David and thank him.” Sometimes, she’s been unable to control her anger when people have said, “God bless you.” She replies, “If God wanted to bless me he wouldn’t have taken my son.”

The community—as much as it may believe otherwise—didn’t know her son. In fact, there is no community. David grew up and attended high school in Woodbridge, a clump of strip malls and highway interchanges indistinguishable from the DC sprawl that surrounds it. Sonja moved out to this little house on Lake Arrowhead, because she hoped he’d be able to relax here. He’d be able to walk out the back door and fish all day long, and they’d be together. It was the rural peace Sonja always wished she could give her son. When David died, one of the neighbors remembered how she used to drive by and see him out fishing; David looked so happy but alone that every time she wanted to stop, just to say hi. Sonja replied, “Well, why didn’t you?”

- David Ruhren at Lake Arrowhead, less than a month before he was killed (Robert A. Martin, The Free Lance-Star / AP Photo).

David Alan Ruhren was a shy kid who learned early in life that generosity was a safer route to earning friends than playground bravado. If Sonja tended to spoil her son, he made up for it by giving his toys away. When she bought ice cream, he’d bring over the entire neighborhood and the gallon would be gone that day. “I’d buy him a T‑shirt,” she laughed, “and then the next day I’d see a little boy from down the street walk by our window, and I’d say, ‘Hey, that little boy’s got on David’s T‑shirt!’”

Thrifty from a young age, David would save his allowance for weeks. “That little boy always had money,” Sonja says, “I used to call him the richest little poor boy.” When his elementary school took a class trip to an amusement park, one of David’s classmates from a poor family couldn’t afford the price of admission. Without telling his mom, David paid his classmate’s fee from his own pocket money. While amazed by her son’s compassion, Sonja worried that he’d been taken advantage of. She explained that, since the boy’s family was very poor, it was very unlikely the kid would repay him. David replied, “I don’t care, Mom.”

Just as David always looked out for the underdog among his classmates, he also looked out for his mom. “He was extremely protective of me,” she says. He cared for her whenever she was sick and he was always there to listen when times were tough—and they often were. Not having David’s support and friendship has been the hardest aspect of losing him. Sonja freely admits that she talks to her son as if he were there beside her. He’s the only one who will actually listen to her, she says, and he’s her only true friend. Sonja and David were always more like friends than mother and son. “We grew up together,” Sonja says with a kidlike grin. She was twenty-one when she had David, and from that day forward she lived for her son alone. When he joined the National Guard, Sonja felt jealous for the first time in her life—David had found something that he loved as much as his mother.

“He joined because of me,” she tells me. On September 11, 2001, Sonja was trapped for several hours on the DC Metro train after American Airlines Flight 77 crashed into the Pentagon. David volunteered for the National Guard immediately after. Sonja tried to dissuade him, but David was resolute. When he left for Iraq, Sonja “pretended he was in college.” “I’m the queen of pretending,” she says, because “if I actually let my heart and soul believe, I couldn’t function.”

Sonja refuses to use words such as death, dead, or killed. She refers to December 21, 2004, as the day when “the boys got hurt.” When she talks about losing David, it’s just that—she’s lost him, but someday she thinks she’ll find him. In a very real way, Sonja Ruhren believes that her son might still be alive. The bomb disfigured David badly enough for Sonja to hope that there might have been some mistake when Mortuary Affairs processed his remains. She hopes that David is in a hospital somewhere with someone else’s dog tags, that someday he’ll walk up to the door and say, “I’m sorry for what I’ve put you through, Mom, but I’m back.”

* * *

A few weeks after the chow hall bombing, I found myself walking up the ramp into the shadowy interior of a C‑130 Hercules. My life seemed to pass before my eyes—not because I was close to death, but because I couldn’t believe I was alive. I didn’t speak to anyone on that flight out of Iraq, not because of the noise—soldiers learn to deal with that—but because I wanted so badly to be alone. I drifted in and out of sleep, half-dreaming about the hundreds of missions, the days and weeks spent pounding pickets, the faces of the Iraqis I got to know so well.

I thought about the weird, marshy smell and the bright colors of the women’s dresses down in that mass grave where I spent a month of my tour, the 3,000-year-old pillars of Hatra on the horizon. When the image floats into my brain, the smell follows. A smell like a dumpster at the beach—sandy, rotten, but unmistakably alive. Alive with the smells of death, with billions of bacteria, and with all of the ghosts who walked among us. I can smell it yet.

How could those months have passed so quickly? A million snapshots rushed through my head as I roared toward home, some from memory, others from the library of photos I snapped and constantly pored over. Now I realize that it didn’t go by quickly at all. It’s still going on. I don’t spend any less time thinking about Iraq today than I did my first day back home. If anything, I think about it more than ever.

During three years at the University of Virginia that followed my deployment, I studied literature with a passion that can only be described as addiction. I continued full course-loads during the summers. I trained obsessively for marathons and triathlons. I filled every single minute of every day. I had no capacity for idleness, and I still don’t. Anything approaching relaxation triggers unbearable feelings of guilt. When I have felt tired or unmotivated, I think to myself, “David and Nick would love to be writing a paper right now,” or, “David and Nick would give anything to go for a run.” That may be clichéd, but it pushes me forward. It also keeps me locked in the past.

I keep thinking that I may be able to accept my role as a civilian when the war finally ends. Maybe then I’ll be able to breathe and not feel as if I’m wasting oxygen. But until that day, I’ll continue to believe that I haven’t done enough, that I should be in Officer Candidate School, that I should use my education, like Richard Hursh, to “help the troops on the ground, save lives, make it easier.”

I’ve contacted recruiters more than once. I’d go back; it’s just that I’m no longer willing to risk what I have—what I want—for what I feel driven to by guilt. Which is to say: I don’t want to go back. I want to be happy. I want to learn how to be a civilian again. I want to learn how to let go. But for some reason, I can’t believe that I deserve any of those things. And if I have learned anything from the men I interviewed from Third Platoon, the families of those killed in Mosul, it’s that I’m not alone.

There’s not a single one of us who feels like we’ve done enough—whatever that means. Several of my buddies are still serving in the Guard. A few of them are in Iraq now. Since I came home, four more names have been added to Charlie Company’s roll call of the fallen, four more young men consumed by the war. And it will continue consuming us, literally and figuratively.

The next president may bring the troops home, but this war will never end.