1

Standing in line at Miami International at dawn, in a crowd whose sense of order was loose at best, Tom, my uncle, confessed to a stranger next to us that this was his first trip back to Cuba since he left the island at the age of nine in 1962. Same for my father, who was fifteen when they landed here that summer. He lagged behind us now, watching an attendant crank his last suitcase into a suffocating shawl of blue plastic, like a beetle prepped by a spider. We were surrounded by mounds of this stuff: shrink-wrapped luggage stacked chest-high, only a fraction of which contained what each passenger needed for the trip. The rest was stockpile.

I was surprised to be in line at all. Hurricane Gustav had been barreling toward Cuba as if to beat us there. We’d been up since three that morning, staring at the Weather Channel, obsessing over forecasts, calculating and recalculating the likelihood of a takeoff according to the storm’s path. Judging by the smeared radius of bad weather on the hotel television, our odds didn’t look good. But we had our tickets, and the line kept inching forward.

So far as my father and uncle knew in the summer of 1962, the trip to Miami was a vacation. They wore hand-tailored suits, because flying was a privilege then, and you dressed for the occasion. They were greeted by a family friend, a pal of my grandmother who’d fled the year before, who met them at the airport with a young priest in tow—a French Jesuit who escorted the boys to a camp tucked into the pines of North Miami called Matacumbe. It was one of several camps that composed the Catholic Welfare Bureau’s Peter Pan mission, through which Cuban children were extracted from what had become Castro’s solidly Communist regime. By then, our family farm in Quivicán had been confiscated, as had the family business—a cracker company, of all things. The family wealth had been looted. The Bay of Pigs invasion had failed, and my father’s uncle had begun a nine-year sentence at the Isle of Pines prison for his role in that debacle. Clearly, it was time to get out of Cuba if you could. Arrangements were made. The boys were sent first. René, the middle son, was already dead, struck by a car while retrieving the visas they would need to travel. He was buried in the suit he would have worn on the flight.

At his young age, Tom could fathom some of this, but he wasn’t freighted with the gravitas of fatherland. My father, on the other hand, was man enough to comprehend leaving Cuba in all its political and existential depths, an awareness that sowed a distinctly Cuban brand of poisoned nostalgia. Nothing from his childhood can be revisited without a piling on: his uncle’s imprisonment, his grandfather’s humiliation in seeing a life’s work confiscated, the death of his brother, the separation from his parents, and the gentle nightmare of waking up, day after day, year after year, in exile. For my father, all of these memories are rooted in the Revolution, so that it took years of prodding—and the recent realization that the Revolution might outlast us both—to get him to acquiesce and fly home. As for Tom, he was ready years ago.

The flight was packed. Among the thirty-somethings dressed in witch-pointed boots and glittering shirts, wide-eyed guajíros stumbled in wearing three hats stacked, so as not to damage them in the luggage. Some of the elders seemed clueless as to what the overhead compartment was for, or even how to read the numbers along the aisle that would guide them to their seats. The stewardess looked impatient; the aisle was approaching chaos.

Outside, the Miami sky was cleaving between a pink clarity and the purple shelf of the storm, Gustav’s edge, the threat growing with every minute that we were grounded. The stewardess began to bully people into their seats. You could smell nail polish. A couple of women began spreading their lipstick, getting ready. This was the event.

Soon, barely settled, we pushed back from the gate and were off—Tom on the aisle, my father in the middle, the window mine. The plane hurtled down the tarmac, straining for lift, then hiccupped off the earth to applause. We bumped through some bad air, then broke above the clouds. I asked Tom about the plane they took to America.

“It was a DC-3,” he said. “A tail-dragger.”

“No,” my father said. “It was a Constellation. The one with the three tails in the back … kind of high … KLM.”

“No way,” Tom said. “DC-3.”

My father looked at me. “Well, Tom knows.”

I offered the window seat to my father. We switched, but I kept an eye on him while Tom and I chatted. He was too quiet. In a few minutes he gave up the window to Tom and sat in the middle, with nowhere to stare but forward, at the headrest in front of him.

“You don’t want the window?”

He glanced at me, but he wasn’t listening. He had the glazed look of a pile of worries, a calm paralysis. He shook his head but didn’t answer, and rubbed his nose, and rubbed it. And he kept shaking his head, gently, but with persistence that meant he didn’t realize he was doing it, preoccupied with some memory that was massive and vivid. He shook his head, but he wasn’t answering anything; it was simply a motion, like a Parkinson’s twitch. Something had been triggered—the view had shaken something loose—and he could only sit there quietly, answering himself. I’d seen him furious, violent, pensive, immaturely buoyant, but I’d never seen him vulnerable. And in the glassy distance of his stare, in his hesitancy to speak, I saw a vulnerability that made me second-guess the wisdom of this trip.

He leaned toward me and whispered, “When we left Cuba, Tom was nervous. So I gave him the window seat, to keep his mind occupied.”

As he said this, his eyes were wet, and for a moment both he and Tom were looking at me, before Tom turned back to the window. In a while, they were both staring out at nothing, a white void of clouds.

Finally, the plane tilted forward, just a little. As it descended, a verdant Cuba surfaced, a serene gray light making the palm trees a little sharper, the foam of the coast a little more brightly white. “It feels like the same plane,” my father said, meaning, in his mind, the Constellation.

We had about ten minutes of powerful nostalgia there on the tarmac, my father’s arm draped around Tom as they walked, the dark clouds casting a moody backdrop to the prodigal sweetness of the moment. We could feel cool air slip through the opened doors of Terminal 2, dedicated to flights to and from Miami.

Inside, the mood was a pressure drop. Agents in blue, agents in khaki, employees in uniform of one kind or another—they all stared at us. Two lines formed leading to two slots, blocked by two red doors. An agent examined your passport and customs forms, asked a few questions, stared at you, and took your picture. Our line was long and slow, and I couldn’t understand what distinguished it from the next one. We waited, watched for a clue. Above the slot was written, with marker on a slab of cardboard, VIP. A lady agent in khaki saw me considering and invited us to proceed—and why not? We were Cuban-Americans on a homecoming. I figured there would be cocktails waiting.

So we entered as VIPs. Just then, the hospitable woman in khaki reappeared and steered us toward a makeshift room where a few elderly women had gathered, looking very patient. Apparently, this was the VIP room. We were encouraged to sit on patent leather couches and have bottled water if we liked. Tom started digging through the tiny fridge tucked in the closet, and, with his confidence back, immediately started hamming it up, teasing the khakied agent. “¿Dondé está la cerveza?” he barked, pretending to be impatient. “¡Soy un VIP!” She stiffened a little. Hospitable or not, she worked for the airport, and the airport was nothing more than a subsidiary of the state, which could give a shit if we were wasting half an hour in the VIP room. The luggage, meanwhile, snaked through the baggage claim, in and out of sight.

A hired boy finally brought it over, but we spent another hour paying more taxes, visiting other windows, other agents. The closer we got to the exit, the more convoluted the interruption. Finally, a pair of girls—twenty-somethings—who asked for our passports and paperwork stopped us. We all leaned in at a tall table—now painfully close to the door—as they asked us, with a detachment that suggested a drowsy interrogation, where, exactly, we were headed once we left the airport. I gave them the name of a hotel I knew. Did I have a reservation? No. Why were we here? To see family. But you’re American? My father was born here. When did you leave? 1962. Why are you coming back now? To see family.

They split us up and asked for a family member’s name and address. I happened to have one written down, but my father and I hadn’t rehearsed this part. I knew he was providing a different name than I was. Tom, meanwhile, kept quiet. The girls led us back to the table, and then took our paperwork with them into the crowd. We looked at each other, at the drug-sniffing cocker spaniel, at the soldiers in blue. The thrill of the landing had evaporated.

The girls returned. With jaded smiles they handed back our paperwork and welcomed us home. It was raining by now and a huge crowd had gathered at the exit, but the rain didn’t seem to faze them a bit—anxious, searching, and soaked.

By the time we reached Centro Habana, dark was falling, and Gustav was upon us. We had rented two bedrooms in an apartment near the university—with air conditioning, my father’s only prerequisite. But soon the lights flickered, the power went out, and the AC rattled to a halt. We unfolded the jalousie shutters and found the entire city pitched in darkness, save for the top floor of the hotel Habana Libre across the street, its sign furred by a brightened rain. We spent the evening talking by candlelight and mopping up the water that blew through the shutters. Then the eye passed, the sky cleared, and by the light of dozens of candles, people began to step out onto the street. The block had a narrow, theater-set intimacy; the balconies were close enough that neighbors could talk across the street without raising their voices. Mothers in curlers traded updates with the neighbors’ daughters. Half-naked husbands leaned out windows to watch the passersby. A woman shook maracas and prayed. Dogs howled; a rooster joined in.

And all night that rooster wouldn’t quit. It was still going by mid-morning when my father and I stood on the balcony, overlooking the street. The storm seemed to have wiped the industrial grime, the congestion of diesel and grease, all away. My father, too, seemed clearer, more together now, and he was telling me about why he’d been so quiet on the flight.

“I felt like I was on a … on a return flight … on a two-way trip. I’ve taken maybe over a thousand trips between 1962 and yesterday, and it was like all those trips were erased.”

He paused, watching the action on the rooftops—a girl hanging laundry, a dog sniffing the air.

“Listen,” he said, “my experience when I left here—it was kind of tragic. The guards showing up at my house. Seeing my mother cry. Seeing my grandfather lose everything he built. Seeing my father move from job to job. From ’59 to ’62, it was terrible, and I was flying back into that.”

“Soldiers showed up at the house?”

“They needed a car. They knocked on the door—a woman and three or four men, dressed in greens and with rifles and machine guns. They sat in the living room, and they asked who owned the car. My uncle had a brand new Plymouth Belvedere, black and white, and they took it. He just handed them the keys—for the Revolution. And days later, my uncle and my father drove around Havana and found it, abandoned.”

We stared out at a diesel truck coughing up the hill.

“What happened at the airport,” he said. “That interview. That was exactly what I was afraid I was going to go through—exactly. I didn’t know it was going to be like that, but I thought, you know—I thought they were going to pick on me again. And as soon as I landed, sonofabitches, that’s what they did.”

2

My great grandfather, José Rifé Treserras, was the son of bakers from Manresa, in the Catalonia province of Southern Spain. The family legend is that his parents both died of an illness that mystified their neighbors, who thought it was contagious. The bakery’s regulars disappeared; the family was outcast. Rifé fled, stole onto a luxury liner that carried him to Mexico, where, after a bit of drinking and brawling and long nights on benches, he was arrested and deported to the country of his choice. He was twenty when he stepped onto Havana’s harbor.

More struggling and homelessness followed, but his industriousness led to an invention that echoed the family trade: he came up with a clever way to light an oven. An electric lighter. Rifé sold the patent to a matchstick company and used the money to pick up his parents’ pieces: He opened a bakery in Havana that produced what became a ubiquitous family of crackers, known as La Unica. Whenever I ask among Cubans older than, say, fifty, they squint, then fondly remember them. Suffice to say the crackers were popular and profitable, so that by the grace of Cubans’ affinity for a dry, salty snack my grandmother, Rubí Rifé, was born into wealth.

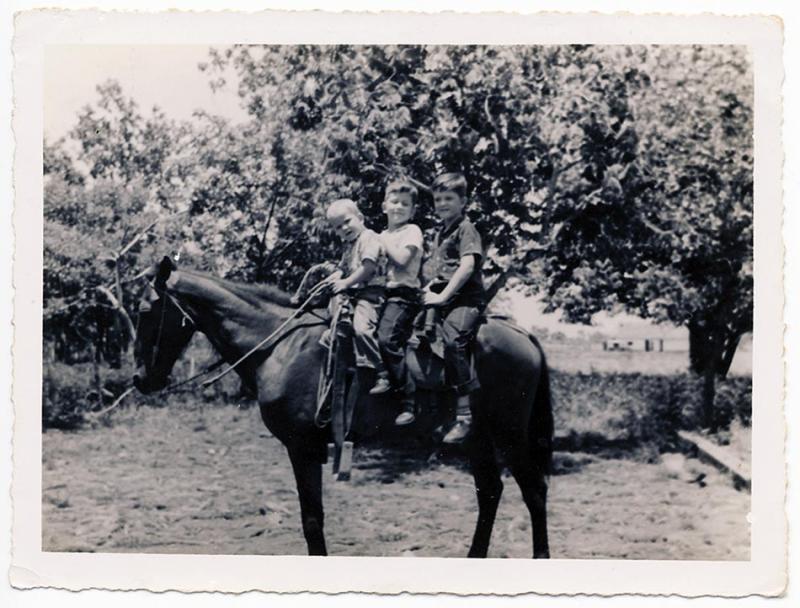

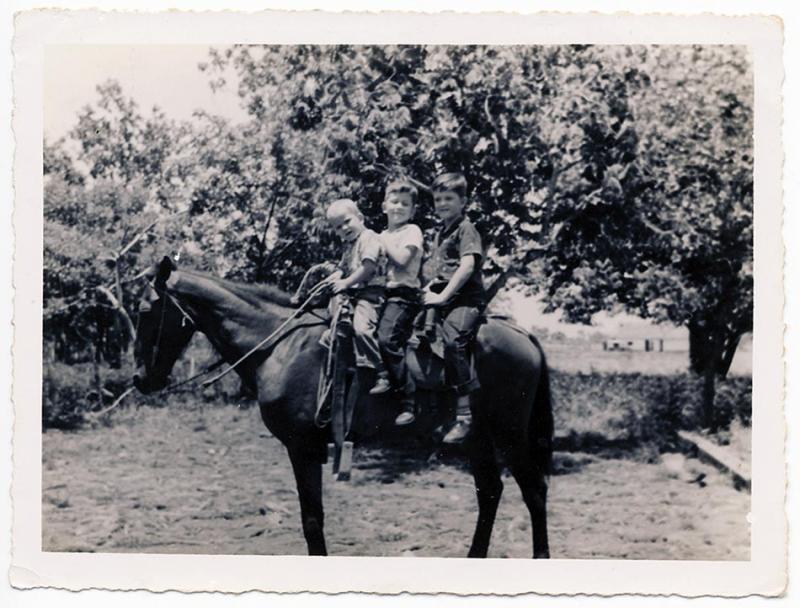

When she was seventeen, Rubí fell in love with a guajíro—a country boy, my grandfather Paul Reyes. Paul hailed from a farming family in Quivicán, a small town about an hour south of the capital. The Reyes brothers—Paul, Maximo, the twins Rogelio and Reynaldo—ran a wildly varied farm of sugar, mango, chickens, plantain, livestock, and rice. On Sundays and special occasions, they’d visit the small central park where a quartet played boleros and waltzes, and, after the sun lowered, boys strolled clockwise around the park’s edge to flirt with girls walking, arms locked, in the opposite direction.

Life in Quivicán was, by all accounts, idyllic. Still, Paul was curious about the city. He left the farm for a job in Havana, moved in with an aunt and uncle who happened to live just a few blocks from Rifé, and met Rubí when his family was invited over for a game of dominos. Paul and Rubí courted. There was tension, just a little, as Rifé didn’t care much for Quivicán, its arid, rural vibe. He preferred the urbanity of habaneros, the sophistication of the city, its Spanish thrust.

Well into Paul and Rubí’s courtship, Rifé arranged for a yearlong family sojourn in Spain. Rubí protested and she was given a choice, Spain or marriage, and chose the latter. Rifé departed with his wife and oldest daughter—the last bachelorette—and Paul took Rubí back to Quivicán, where he rejoined the farm and she fell in with the quiet pleasures of a rural life. The city girl was converted. She lived blissfully as a farmer’s wife for six years and three sons before Rifé had finally had enough.

“There was a ditch,” my father told me. “It happened that we had a lot of rain, and the ditch was full or water—red water, you know, from red clay. So the kids said, We’re gonna play in the ditch! So we were playing in the ditch when my grandparents arrived . . . and the shit hit the fan!” He doesn’t remember what was said, only how forcefully Rifé said it, how livid he was, how his temper shook the house. “He got me out of that ditch,” my father said. It was my father’s first extraction from a place he loved, plucked from Quivicán to be raised in the city, for his own intellectual and cultural betterment.

Rifé’s affection for my father, his favorite grandson, found its form in discipline. He put the boy to work—mixing concrete for an apartment he was building, digging ditches, laying brick. He even enlisted my father to help build a house big enough for all three generations, in land-rich Alta Habana. Once the house was finished, Paul, Rubí, Tom, and René all followed. Rifé hired Paul as a manager at La Unica and placed my father under the wing of whichever employee he thought could provide a good lesson in the education of a future industrialist, the heir to the company. My father worked on the line, packed crackers into tins, and sometimes rode with the deliveryman through the city’s commercial district, gleaning weird wisdom from the whores who whispered to him as he sat alone in the idling truck.

On weekends, the household split according to passions: Rifé would host a small reunion of Catalans to play dominos in the gazebo, and Paul would take the family to Quivicán to visit the farm. Sides went their separate ways, tending to their separate roots—politely, but religiously. Paul’s brothers never visited Havana, not even on holidays. Christmas, New Year’s Eve, Paul and Rubí would shuttle their sons out to the farm and be back in time to host parties for the family’s Spanish side.

December 1958, New Year’s Eve, the Spanish side of the family was gathered in Alta Habana. My father doesn’t remember it as all that extraordinary an evening, just how curious it was to hear so many cars honking as they passed along the street, how the phone rang constantly. He was twelve and knew little about Batista. And as far as he can remember, that night was the first time he heard the name Fidel Castro.

As romantic as the Revolution might have seemed in 1959, it turned sinister by 1960. With the widespread seizure of property and brutal retaliation against his opposition, Castro had dropped his democratic cloak. The government confiscated La Unica and, in order to diffuse any counterrevolutionary plots, scattered its employees to other businesses.

In Quivicán, several hundred disillusioned citizens—including my grandfather Paul’s brother, Rogelio Reyes—had joined a counterrevolutionary group known as Hermanos de la Causa (Brothers of the Cause) whose mission was to prepare, through a network of isolated cells, support for the CIA’s planned invasion of Cuba in 1961. None of us know for sure if Paul was involved, but he was the only member of the family who knew Rogelio was. Just days before the April invasion at Playa Girón, Rogelio was arrested; the family knew nothing of his whereabouts for a year or so, then discovered he’d been sentenced to thirty years at the Presidio Modelo, the model prison, where Castro himself had been held after his first attempted coup, on the remote Isle of Pines.

Rogelio would serve only nine years out of his thirty-year sentence, but the years were brutal. Hard labor was the routine; executions were common. Back at home, his wife and daughters were shunned as political lepers, and whether out of fear or genuine loyalty to the Revolution, not even Rogelio’s brothers would stand by him—none except for Paul, who shared Rogelio’s disillusion with the Revolution.

Rifé saw the Revolution as permanent, and therefore saw no future whatsoever for his grandsons in Cuba. When he learned of the Peter Pan mission, which could get the boys out quickly, he insisted that they go. Rubí put up a fight, but Rifé—ever the pater familias, ever the Catalan—would bear down (even Paul knew he was right). But just to calm her, he offered a concession, which he knew was a trick: “If I’m wrong,” he said, “the boys can come home.”

3

The streets in Santos Suarez, the neighborhood where Rifé brought my father to live with him, looked as if they’d been hit by mortar fire, and if dodging those holes wasn’t tricky enough, we had emaciated dogs to contend with, trotting along with suicidal obliviousness. Our driver Oscar’s tiny Lada sedan—a leftover of the Soviet tit—weaved and crept along until we hit a stretch of relatively smooth pavement, then darted forward to an intersection. We stopped and asked if anyone knew how to find the street we were looking for, where Rifé’s house was, just down from the school my father attended.

I ogled the architecture, the mash of styles—Eastern Bloc with art nouveau touches in the ironwork, and two-story Caribbean concrete boxes, lightened a little by tall jalousie doors and windows. Every house we saw derived from stone, and the patina of the old bright paint stained by decades of neglect created that Havana tinge of majestic dilapidation. Even the bad ideas had a beautiful flair.

We turned onto d’Strampes Street, battered and gouged by potholes. My father tried to remember directions, didn’t know the cross street, was just trying to jog it loose. “There was a major street that had a trolley,” he said, and we pulled over and asked an old man if he remembered it. “Right over there,” he pointed. “Santa Catalina.”

Santa Catalina! We darted down d’Strampes clinging to the handles, suffering the Lada’s stiff shocks, and shot across Santa Catalina toward the school.

We walked up to the gate of the school, a Spanish mansion that presided over many marble steps, flanked by clusters of tall palms. My father dragged his hand along the wall the way he did as a child, all the way, three doors down, to Rifé’s house—a narrow, two-story melon-colored neoclassical.

A woman came out, followed by a man in nothing but a pair of shorts. My father explained who he was, that he’d grown up here, and with groggy delight the couple retreated to put the dogs away, then invited us in. The shirtless fellow was all apologies, but it was drenching hot and not even noon. It was his house anyway, no worries.

We went up the stairs and down the narrow hall, brightly lit. At the end of the hallway was a small room painted in robin’s egg blue; the French doors, paned in frosted glass, that led to the balcony were wide open.

“I’d take naps in this room,” my father said. In the heat it had a drowsy peacefulness. “There was a guy, Alfredo, who came by with a horse and rang a bell and woke us up, and my grandmother would take us down to get ice cream.”

I hustled over to the balcony to take a few pictures while my father stayed in the room, staring around. The hostess was explaining the tile work to Tom in the hall. I passed through the blue room again to join them, aiming at the tile.

“Oh, he’s getting sentimental,” the hostess said. I glanced up to see my father looking weak, as dizzy as he had on the flight, but in company now, embarrassed. She walked over and rubbed his shoulder, then drifted off down the hall, where Tom followed.

“In this room,” he said. “I think René saw his death. One night he woke up—”

“You were here together?”

“Yeah. He woke up screaming.”

“What did he say?”

“I don’t know. It was weird. It always stuck in my head. In a bed just like that, and he woke up screaming. Screaming … incredibly loud. Jumping. Saying, No, no, no.”

“He never explained it?”

“No. And years after he died, I related it to that night. Because it was so intense.”

Tom called to us from downstairs and we headed down and caught up with the group. We traded continental kisses with the women, cheek-to-cheek, shook hands, and promised to take them up on their invitation to return.

“See,” my father said, back in the car, pointing to Santa Catalina and a stretch of old tracks. “There were trolleys.”

We headed down Vento Street, and then turned onto San Francisco. My father shook his head at how overbuilt the neighborhood was. Alta Habana was mostly fields when the boys lived here—suburban, but with an openness that has disappeared. We could see the two hospitals that anchored the neighborhood—Nacional and, for children, Infantil, where René was taken after the accident.

“How’d he die?” Oscar asked.

“Motorcycle,” my father said. “Right before we left.”

The blocks were dominated by tower apartments, Eastern Bloc monstrosities that had a kind of municipal suffocation to them. Tom let out a long sigh, and we were quiet a minute. “That’s the hospital right there, isn’t it?” he said.

“This is the hospital,” my father said. “I remember the entrance.” He looked around. “My brother’s accident was on this street. After we pass that bridge.”

“I want to see where it happened,” I said.

Oscar turned down the next street, crossing a bridge that spanned a rheumy creek where the boys would fish, but which was choked with trash now. In preparation for their trip to the States, in addition to getting measured for their suits, they’d been vaccinated—flu, typhoid—and the vaccines leveled them for days. René recovered first and was goofing in the yard with a neighbor boy when, ahead of schedule, a call came announcing that their visas were ready to be picked up. The neighbor boy was anxious to try out the new scooter Paul had bought for his sons, and Rubí knew the situation called for haste. So René and the boy hopped on the scooter and shot out toward town. The neighbor boy drove; René rode on the back.

After the bridge, we took a small hill, and then my father recognized the intersection. We pulled over, in front of what looked like a school bus depot, with a handful of goats grazing on the grass just behind a chain-link fence.

We got out and stared at the street. Tom remembered a witness telling Rubí that he’d heard René call out—to slow down, or watch out, he couldn’t remember. And over the years rumors and variations of this moment have surfaced and receded, giving their brother’s death a kind of Rashomon truth: that the driver was drunk, that he had run the stop sign, that René was riding alone, that my father rode on the back, that René somehow burst through the car’s windshield, or crashed through the rear passenger glass and died in the driver’s backseat. The truth is that the boys were speeding and struck the car’s side panel. The neighbor boy slammed against the hood, bruised but otherwise fine. René catapulted off the back of the scooter, over the car, and landed on the other side, his skull cracking against the curb. The hospital was close, but only served for a three-day vigil before he died.

My father explained all this to Oscar, talking with a storyteller’s buoyancy. “Immediately after that, we left, and my mother didn’t see us again for five years. And she asked my grandfather, ‘Please don’t let them go.’ And my grandfather, who had that Catalan temper, said, ‘I know what it means to be a Communist. I lived in Spain. You have no idea. If I’m wrong, they can return, but for now get the boys out.’ My mother didn’t want to do it.”

“She had a breakdown,” Tom said. “She spent months in bed.”

“A mother never recovers from that kind of thing,” Oscar said.

“Tailors made us suits for the trip,” my father said. “René was buried in his, here in Havana, in the same cemetery as Rifé. And when my parents finally left, they asked our family in Quivicán to come and get him, and bring his remains to Quivicán, where he is now.”

“That’s why you all are going to Quivicán,” Oscar said, putting it together.

“And just before I left, my mother wrote me a note—”

He walked away without finishing, down along the sidewalk, and began to shake. I had never known about a note; neither had Tom. And its mention seemed to surprise even my father. I watched him, his back turned to us, his arms folded, hand on his face, and as he shook I could hear him sob—chillingly foreign coming from him and made lonelier by how faint it was under the noise of trucks.

4

Quivicán was dusty, crippled. The low-slung houses that surrounded the park, with fluted columns on front patios, reflected a woebegone Spanish elegance with Moorish touches in the tile work. But what had been built since the Revolution seemed to clog the town with a pragmatic, unimaginative spirit best described as Soviet Rural—hasty, square, soulless. The dirt side streets were rutted and pocked. Pigs were penned for meat, and hardly a block was spared from the sharp stink of a trough’s rot.

The cousins knew I was coming—I’d called Bebin and Pedrin, my great-uncle Reynaldo’s sons—but I hadn’t told them that my father and Tom were with me, partly out of paranoia (was there a grudge for all the silence?) and partly to orchestrate a more sentimental moment.

Which worked, sort of. We had pulled into town knowing only vaguely where Bebin and Pedrin lived but were pointed toward a blue Chevy (painted with what appeared to be house paint) parked in front of a two-story block house. Bebin’s wife, Mena, answered the door. I’d forgotten about her natural enthusiasm: When I introduced my father and Tom, she shouted and fluttered her hand to her mouth, wide open, and touched her temples. She then led us toward the back, where Bebin kept his shop—a green, greasy bunker-like workspace packed with motors and car parts and buckets of oil. He stood shirtless, hairy and hunched over a workbench, attacking a fuel pump, and Mena demanded he turn around—look!—and he shuffled over like a Giacometti figure waking up, whittled by stress. And to the extent that I’d forgotten his wife’s flair, so, too, had I forgotten how understated Bebin was, so much so that I wasn’t quite sure if he was angry, or choked up, or what.

“Bebin,” my father said, “you remember me?”

“Look!” his wife said.

“It’s my father,” I told him.

He blinked. My father hugged him, and Bebin returned it shyly, with a nonplussed calm. “It’s been a while,” he said.

“Forty-six years,” my father said.

“How’s it going?”

“How wonderful!” Mena said.

Tom walked up, more hugs, and Mena must have felt compelled to explain her husband’s reluctance to embrace us. “He’s sweating,” she said, with some excitement. And it was true, though the sweat was mild compared to the grease that coated him.

“You guys moving to Quivicán?” he said.

“Where’s the jeep?” Tom asked.

“It’s history,” Bebin said.

“And Pedrin?” my father asked.

Bebin pointed behind him. “He lives right over there. He’s been busting his ass with a diesel pump.”

I asked about the farm, excited to see it.

“The farm?” Bebin said, warming up a bit now. “You can’t recognize anything. It’s all overgrown. You remember when we lived there? Now, I go there and I get confused. I don’t know where anything is because they bulldozed the houses, everything.”

“Forty-six years,” my father said.

“The old folks are gone,” Bebin said.

My father offered, “My mother’s doing well.”

“How old is she?”

“Eighty-two.”

“Ah. The old man died not too long ago—eighty-four.”

“That’s a long life!” Tom said.

“Yeah. Carmita died. And Uncle Juan died, too.” He was in a rhythm now, lightening as he ticked off the names of the departed. “There’s nobody left,” he said. “Only Otilia and Rubí are left. Oh, and my mother’s sister,” Bebin said. “She’s demented. She looks like a skeleton.”

He paused. “They’ve all faded away,” he said, almost chipper. “But that’s how it goes.”

In the distance someone was working with what sounded like a table saw, a high buzzing—but awkwardly, in pulses, as if shy with the blade.

“And this one!” he said, pointing at me. “He got sick the last time he was here. Did he tell you?”

“Yeah,” my father said. “Got the shits!” And they all started laughing.

“It was hilarious,” Bebin said. “He was a wreck.”

Just then Mena returned with a message: Bebin’s son needed to borrow a No. 20 wrench. Bebin grabbed one and sauntered off, and we occupied ourselves by snooping through his shop, gazing into buckets of oil to see what lay at the bottom, breathing in diesel and burnt metal, lolling under the music of shy pullets huddled nearby but out of sight.

Pedrin arrived, and the booze appeared with him. He didn’t bring it, but his presence—a hulking man, a kind of pear-shaped bear, mustache and glasses somehow adding to what seems like a lazily terrible strength—inspires the presence of beer and rum. We sat out on the patio, on the aluminum rockers, and set all three fans oscillating at high speed, pushing a hot breeze around the place.

Pedrin asked my father, “José, how old are you?”

“Sixty-one.”

“So Tomasito’s … fifty-eight?”

“Fifty-four, fifty-five.”

“Oh, right. René would have been fifty-eight.”

“He would have been … sixty,” my father said.

Tom emerged from the kitchen with a round of beers. “Man, I wanted to see that jeep again so bad,” he said.

“And is the farmhouse really gone?” my father asked.

“Gone. Nothing exists. And if it does, you wouldn’t be able to find it. It’s all overgrown.”

“The tractors?”

“Not even their smoke.”

The plan had been to visit the cemetery alone. But in the time it took to ease through a few beers, Mena had arranged a parade of lost acquaintances. She led us through the town’s wide streets to the house where the boys grew up and a hairdresser lived and worked now, to revisit the town’s only cinema, to see the park bench where Tom cracked his head. She greeted nearly every neighbor, who greeted her in turn.

We came finally upon a woman who had demanded to see us. Apparently, she had cared for Tom, René, and my father when they were children. She was eighty-four now. Rubí never did know what her actual name was, only called her by her nickname, La Niña.

“Come here,” Mena hollered to her, “come see the boys you used to care for! The woman you worked for, her sons. Look at them!” And, in fact, La Niña recognized them, with hugs and kisses all around—even for me, beneficiary of the momentum of her affection.

The wind was picking up, the sky growing darker. I began to worry we wouldn’t make it to the cemetery. There was a rush of talk of lost and living family members. “My favorite was René,” she said. “I was delirious over René. He was a little gift. I remember one day I brought him with me to the butcher, and this old woman came over and wanted to touch him, he was so beautiful—all of you were—and she gave him the evil eye and right after she touched him, he went cold. I thought he’d died right there. I didn’t know she had the evil eye. But she killed him, I swear it. So I ran with him from the butcher’s over to those people over there, a couple who dealt with this kind of thing, and I threw him down on the bed and told them he’d been given the evil eye. They read a prayer over him—you know de San Beltrán—and as soon as they finished, he began pissing the bed, piss shooting straight up into the air, and I screamed, He’s pissing the bed! And they said, don’t worry, let him piss the bed. After that, he was fine.”

“Why’d she give him the evil eye?” we asked.

“Because all you boys were beautiful.” And until I cleared it up back home—that the evil eye sometimes had a mind of its own and could be dispensed not only in malice but also by accident—I spent the rest of the trip imagining the fantastically petty and dangerous politics of handsomeness in Quivicán, where if you were too good looking, they’d find a way to get you.

If there was anything but woods on the far side of the cemetery, we couldn’t tell. Two streets ended at its entrance on what seemed like the backstage of town. Mena was talking, but I had tuned her out, my Spanish almost deliberately weak. We dodged a mound of crushed aluminum cans, waved half-heartedly to a handful of laborers idling near a truck. One of them started whacking at something in the bed, chopping at it with a machete. I could see the entrance to the cemetery, and at this point, worried that she would ruin the moment, I asked Mena to meet us at home. She agreed, but kept walking with us and chatting up those within earshot.

Until I showed up in Quivicán, eight years ago, the whereabouts of René’s remains had been a mystery. Not even my father knew where his brother was—or, at least, had assumed he remained in his original grave, in Havana’s Cemeterio Colón. I went there on my father’s instructions to see where René was buried, in the same mausoleum where Rifé was interred, in the vault of los Catalanes. I had arrived during an exhumation of corpses that had been scheduled for smaller graves, to make room for the incoming dead. I met a groundskeeper, an elderly man swallowed by his clothes, a Yorick of sorts with a homemade broom. He pedaled slowly on his bicycle as I followed him to the tomb where René was supposed to be. Inside I scanned the small chambers, a family of corpses linked by country more than blood—and region more than country. But I couldn’t find him. Only Rifé’s tomb, misspelled so it read: josé rifer treserras / 4 October 1966.

What I discovered days later on that trip was that René had been moved. And what we discovered this time around was that it had been Rubí’s idea. She had wanted to do it herself, to lay her son to rest where he’d be happiest, with the family in Quivicán. But when their travel visas came through, she and Paul were forced to pack quickly, before they could move René themselves. And so, just days before her departure, she begged the family to come to Havana and retrieve him—to rescue him, in her mind—from the anonymity of Cemeterio Colón, where no one would be left to visit him. Paul’s brother, Rogelio, tried several times and failed; each time, René had been too well intact to be removed. It wasn’t until some time after Rogelio had fled the country, after I was born, that Bebin had finally brought René back to Quivicán.

A tractor passed. The man with the machete whacked away. We approached the arch, and walked carefully—searching, voices low—into that small cemetery of tombs aligned above ground, a blocky marbleized park. With a grin and game-show flair, Mena walked up and waved her hand over the family grave—as if this, too, were a cause of civic pride. Everyone fell silent. She sensed her cue and walked off, without a word, and Tom, who had been quiet since we set foot on the side street that led us here, almost as soon as she was gone and the whacking of the machete paused, as soon as we found ourselves wrapped in a country silence, began to tremble, then shake and groan. The more dignity he tried to muster to control his weeping, the more awkwardly it forced itself through his body. My father held him, kissed his neck. Tom was blubbering, and I could hear it from a distance. I only then realized, as if, after all it took to drag these men here, that when it came down to it, I wasn’t altogether sure I belonged. “It hurts,” I heard Tom say, and their hold on each other tightened. “Fuck, it’s been in a long time.”

They let go, and I approached again, and we noticed an overturned plastic soda bottle, and, turning it right side up, almost all at once realized our mistake. “We should’ve brought some flowers,” Tom said. “We didn’t even think about it.” My father shook his head. The machete began again.

5

My father wanted out. The airport, the neighborhoods: in a matter of days we’d trotted through a vigil for a childhood interrupted. I had anticipated creeping toward these emotional watersheds. But Gustav had thrown us off, tightened the trip’s deadline. So we darted from spot to spot: the house where Rifé brought my father to live; where my father was put to work the next year (La Unica still in operation but with only an elderly woman idly guarding sacks of flour); to Quivicán, where the past crashed down in fits but the dreaded specter of politics was salved by pork and rum and artful bullshitting, by legends of the farm and the physical reality of René’s grave, the mystery of his whereabouts finally made palpable. Through it all, we never stopped sweating. My father, for one, was visibly thinner in a week’s time, his belt, notched by habit, sagging below his waist button. Rather than clearing the air, Gustav had brought a worse heat in its wake.

Even after it had passed, el ciclón was the sanguine comic excuse for why nothing worked, for why, days after the storm, Havana’s neighborhoods still didn’t have power. The Malecón remained dark at night, the streetlamps black. Thousands of teenagers, strolling or idling or flirting, gathered along the water in eerie multitude, like sea lions on a pier. Rumor was that those trolling the park along Avenida Presidente were there to get high and that the pot was awful. But that seemed about as good an evening as one would expect on a Sunday night without power, half-stoned on Gump weed with a shitty taste in your mouth, a nice breeze and a lover’s thighs draped across your lap. While the streetlamps were off, even Havana Vieja was dead, full of hustlers who approached us so relentlessly that my father defaulted to singing thank you, thank you the second anyone approached (the “no” implied), as automatic as if he’d won something and was being celebrated. Not even Tom had the energy to banter with them. Hurricane Ike was bearing down, and they were emotionally tapped. Done. And I couldn’t blame them.

We arrived at Terminal 2 under a copper sky and lightning to the east. I didn’t bring my bags, because I intended to stay one more night, just one night alone at a hotel to think it all through, to watch channels broadcast from uncensored places, to gorge on news. I craved the West; I craved English. But just one more night in Cuba, alone, would do some good. Ike was big enough that, with the eye still over the Turks and Caicos, its edge and effects were touching Havana. It was obvious that half the crowd at Terminal 2 was there to get out ahead of the storm. The place was packed with people, all reunions ending here, in the same hangar through which we had entered—but on the other side, divided so that arrivals were completely separated from departures. Cousins, second cousins, aunts and uncles, generations, extended and intimate. The place was a circus, a pageant of the lucky ones leaving. I couldn’t help but sense a dose of arrogance in it, an element of self-consciousness, especially among the young, who were wearing their best for the flight.

In particular, a girl in white, rivetingly pretty, with thick black hair, green eyes. I had seen her just a couple of nights before, stepping out of a limousine at the Hotel Cohiba, arm in arm with a man thrice her age who was dressed in a black suit and red tie, shadowed by what looked like a bodyguard. It could’ve been her grandfather, or her john, or who knows what. But she wore the same coy smirk now as she did while hanging on his arm. She looked around to see whom she could see. Her entourage was enormous, about twenty strong. She wore a white full-length dress that shimmered and seemed more appropriate for a first communion or wedding than for a hectic exit. When she recognized a friend, they issued triple kisses cheek to cheek to cheek.

“Well, it worked,” my father said and waved his ticket. Tom and I had been watching the terminal’s television, listening to the state weatherman as he painstakingly described, over a hand-drawn trajectory of the hurricane, the details of air pressure and what it foretold.

Tom smiled at me. “What are you going to do?” he said. “You better get the hell out of here tomorrow, boy.”

“We’ll see,” I said. The festiveness was rattling the concourse. Reggaeton blasted from a glass counter that sold Cuban chotchkies. By the crowd’s noise and logic, we funneled toward the barrier of red doors, exactly like those we’d passed through on arrival. The party was still on, the laughter loud, but nothing was happening. We were where we were supposed to be, huddled at the elastic dividers past which only passengers were allowed.

And then they began to filter through—one by one toward whichever empty slot the guard chose. The noise in the room didn’t dissipate, but separated, as the families that had arrived to see each other off on the next flight were now sharing the room with those who were actually saying goodbye. And in that noise, pressed there in the crowd, the mood shifted. The girl in white emerged and entered a slot, and suddenly, as she glanced away from the agent inspecting her visa toward where I stood, her expression crumbled a little. I looked around. I was standing next to her mother. And I realized that all the coyness and flitting, the pride of selection, was just a put-on that deferred the reality of this moment. All around me, boys in their best shirts—satin, some sleeveless, one silk-screened with Al Pacino as Scarface, another black with a metallic glint—weakened and began to fold their pride as they leaned against the elastic divider. The boisterousness had been a prelude for this meltdown. Here were mothers for whom death was closer than not, and who couldn’t say for sure if they’d see their sons again. Here were savage-looking brothers whose faces tightened with pathetic grace, ashamed of their tenderness but adoring of a sister who turned to pass through that red door—reluctantly, but never pausing, despite the disappearance it guaranteed. This was the embargo fully manifest, these families that I’d heard about, read about time and again, but whose ritual of separation I hadn’t reckoned until now, until this coquettish little snot in a prom dress suddenly blossomed with anguished humility.

Only to be followed by my father as he and Tom took two slots, fanning out, so that I had to weave back and forth through this weeping crowd to get a look at them. And I knew Rubí then, in that moment, more than I’ve ever known her growing up. I knew my father and Tom as boys in 1962. Seeing my father standing in his slot, dutifully awaiting his permission to leave, I understood his anger—and Rubí’s. That separation was more intimate, and sickening, than any I’d ever known. And as I watched him, his body shifted: he was free to go. He looked, grinned a little, and saw the faces around me, and turned to open the door and slipped through, glancing back one last time over the rim of his glasses as the door closed, holding it open, smiling, relieved, and lingering there just a second, his expression relaying a tender message.

I had the exact same look, I know it. But I brushed it off, afraid of what it ushered in: that after years of prodding at his reticence, of trying to bridge the distance that Cuba had dug in him, of bemoaning how the pain of Cuba had made him a man who kept mostly to himself, and despite one frustrating mystery or another, I loved him now—suddenly, clearly—unconditionally. There was nothing left to solve. He had nothing to prove and never really did. It was a terrifying intimacy to have in that crowd, in that place, and, scared of it, I laughed a little and ducked behind the old women blowing kisses to the boy in the next slot and kept going. I found Tom, who had just wrapped up; he flashed a big smile as if to say, See you, sucker! then turned and darted through the red door. I hid in that lighthearted moment and didn’t look a single stranger in the face. All the way out of the airport, I kept my head firmly down.

In the car again, pulling away, I asked Oscar to take me to the hotel, and stared quietly out the window at the road—at carts and horseshit, at people staring back. At Fidel’s august portrait on a factory’s façade.