On November 25, 1956, Fidel Castro and eighty-two revolutionaries crammed aboard a small yacht, slipped out of the Mexican port of Pozca Rica, and steered for Cuba. The yacht, called the Granma, is all white paint and leisure, a decadent vessel. It now resides in a glass cage at the Museum of the Revolution in Havana, where it is guarded by bored soldiers. Perhaps it is the glass, or the flash of tourist cameras, but the Granma looks less like a rebel blockade-runner than the S.S. Minnow—the boat from Gilligan’s Island. So it seems natural that, after a week at sea during which the overloaded yacht nearly sank, the rebels ran it aground off Cuba’s southern tip. They were forced to wade into history, dragging revolution along with soaked guns and sand-coated supplies.

Fifty years later a walkway leads through a stinking mangrove swamp to a small concrete monument where they stumbled ashore. You can stand with your back to the sea and consider their path—no walkway in 1956—through the labyrinth of slick trees and deep, standing muck. Crabs shuttling beneath the roots, flies biting. A few miles away another bit of concrete marks the spot where Christopher Columbus landed. Scattered across the landscape near the monuments are piles of rubble, the ruins of houses smashed by a hurricane in 2005. Violent change enters Cuba through here.

Just after Fidel and his comrades reached dry ground they were ambushed and routed by troops of the American-backed dictator, Fulgencio Batista. The survivors, including Che Guevara and Raúl Castro, fled into the forests. Fidel and two others hid in a sugar cane field while the army hunted them. The men lay still for five days, praying the soldiers, known for torturing rebels, would not find them. Fidel was confident. He whispered plans for the new Cuba to his companions. We will win! he was saying. We’re fucked, they thought. And Fidel is mad! Bellies pressed to the dirt, search planes whining overhead, sucking cane juice for sustenance, they hoped just to survive.

At that moment, it must have seemed another disaster, like Fidel’s first botched attempt at revolution in Santiago, three years earlier. But he survived. He has always survived. The vagaries of fate, the suggestion of miracles—cornerstones in the temple of his reputation. Eventually the three got up and ran into the mountains. After days of desperate wandering, they regrouped with eighteen other survivors. Soon they began winning. Two years later the country was theirs.

Today, in a cemetery by the sea, several miles from Fidel’s cane field, the old dead lie in snow-white vaults above the hard brown earth. Beside the graves, living men slump in shade beside stacks of luggage. It seems they have been waiting forever. I’ve been walking this road for an hour and seen no cars, few people. In Cuba only the dead do not have to wait.

I’d been told to take a left at the cemetery and go up. An old man heading the opposite way looks me over and asks what I am doing.

“You wouldn’t rather go straight, to Santiago?”

“No. I’m following Fidel’s route into the mountains.”

The man considers. He wears a white straw hat decorated with the red and blue of the Cuban flag. Veins like ropes in his forearms, a thin gray mustache above his lip. Why?

I came to retrace the path of the revolution, from Fidel’s landing spot here in the deep south to Santa Clara in north-central Cuba, where Che sealed the victory. Using the route as a loose guide through the island, I hope to spend a month traveling away from the big cities, from Havana, to see the country Fidel created before he, and possibly it, disappears.

The old man nods and shakes my hand.

“It can be done,” he says. “Take it calmly.”

Days earlier, in old Havana, I stood on a rotting balcony watching boys hurl slimy bombs at cars passing below.

“Bomba!”

A boy yelled, then crumpled in laughter. He clutched a handful of mango pieces, mostly the sticky, fibrous skins. These were his weapons. The groaning busses with their wide, flat roofs make the easiest targets. They crawl, so packed with sweating commuters they barely clear the pavement. Classic cars, the Fords and Chevys from before the US embargo, are harder to hit. They cruise like sharks, their steel fins battered but the drivers aware and careful, swerving. A car is a precious thing in Cuba, even if polish and parts are all but impossible to buy.

“Bomba!”

The road was slick with mango, the boys’ faces smeared with juice. They worked themselves into frenzy. The man of the house, a retired naval officer, emerged and waved a finger at them and they grinned. He handed me a couple of mangoes.

“You might as well be armed, too,” he said, and headed back inside.

Where I grew up we didn’t have mangoes, we had snowballs. We didn’t have balconies, either. We hid in the woods and fired at trucks and cars, then ran as the drivers chased us through the snow. But the rest of the game is the same, the laughter.

During my childhood, Cuba was described as one of our great enemies, and Fidel Castro was a tyrant who had forced my parents to hide under their school desks, praying the bombas wouldn’t come. They remember it, the drills, the tension. Kennedy on the television. The apocalypse gathering just offshore. Like every other American my age—Grown Children of Cuban Missile Crisis Survivors—I have no such memories, no such relationship with Cuba or Fidel. For most of our lives it’s been easy to pretend Cuba does not exist. In school we were given a handful of words for it: Communist, dictatorship, Fidel. Terms of dismissal.

From the balcony, the city’s crumbling beauty spread to the horizon. The sweet, acid breath of the sea caressing the once-grand buildings and turning them to dust. Nearby, in the colonial center, hustlers trailed European tourists and dodged swarms of cops while selling forgeries of the famous cigars, the Cohibas and Monte Cristos. Some of the girls were desperate, or at least ambitious—at night I saw them on the arms of Dutch and British men two, three times their size. Musicians in the cafes, families picnicking along the great seaside avenue, the Malecón, swimming and fishing beside outlet pipes that flushed the city’s fluids toward Florida.

When I arrived, I was thirty-three. “Be careful!” the Cubans loved to say. “You’re the same age Jesus was when they nailed him up!” I was just a year older than Fidel had been when, on January 1, 1959, he won control of the island and became the second savior to millions of Cubans. He is eighty-one now and still revered, though he abdicated power to his slightly younger brother, Raúl, in 2006, after falling ill with a gastrointestinal problem. He has been nearly invisible ever since.

But somewhere, Fidel is out there. Perhaps he lies in a bed, and in the most modern kind of helplessness he is tethered to machines that keep him alive. Or perhaps he walks slowly in circles wearing that tracksuit, the one he wears in the all the press photos, looking like a grandfather escaped from a nursing home. His beard is gray as old wool. The strong face that confronted the world has blurred. The body is collapsing; some think the mind has already gone. I felt I should hurry. Everyone knows it is only a matter of time.

I didn’t stay long in Havana; I wanted to chase the revolution south. But chase is too vigorous a word for the hot present tense of Cuba. I waited in line for hours to buy a ticket, then waited a few days for the train. The journey was scheduled to take eight hours. But the train left late; the trip took fourteen. No one onboard was surprised.

In Santiago, Cuba’s second city, the air had cooled from sweltering to hot, and at the corner boys played baseball with a broom handle for a bat and a plastic medicine bottle for a ball (it didn’t fly straight but it was durable). Several doors down, middle-aged men sat around a square table in the street playing dominoes, laughing, passing a bottle of rum. Slapping down the bones.

I watched the games from a doorway while a friend prepared dinner. Her name is Celia.1 She is tall, long-limbed, skin the color of coffee. A gap between her two front teeth. She is thirty-seven and she talked as she cooked, partly to her Canadian husband and me. I had asked her for memories of growing up in Cuba. She reached back, her mind fastening on certain things. From there she mostly talked to herself.

You cannot even imagine it.

She slipped the fried plantain chunks back into their green peels and lay them on the counter. With the heel of her palm she mashed them into golden-brown disks, then dropped them again into the oil. She remembered. There was no oil in Cuba then. Worse, there was no soap and no tampons.

Imagine that—just try. To always feel dirty.

A few blocks away and more than fifty years ago, Fidel launched his first attempt at revolution here in Santiago with an attack against the large, mustard-yellow Moncada army barracks. The attack went badly. Castro was nearly killed. Many of his comrades were captured and tortured, their eyes dug out, their genitals mutilated. Fidel escaped but was caught later in the mountains. He was spared death by an officer who told his men not to shoot; he apparently kept saying, You can’t kill ideas, you can’t kill ideas. Fidel was jailed, then pardoned, and then he went into exile in Mexico. Eventually he bought the Granma.

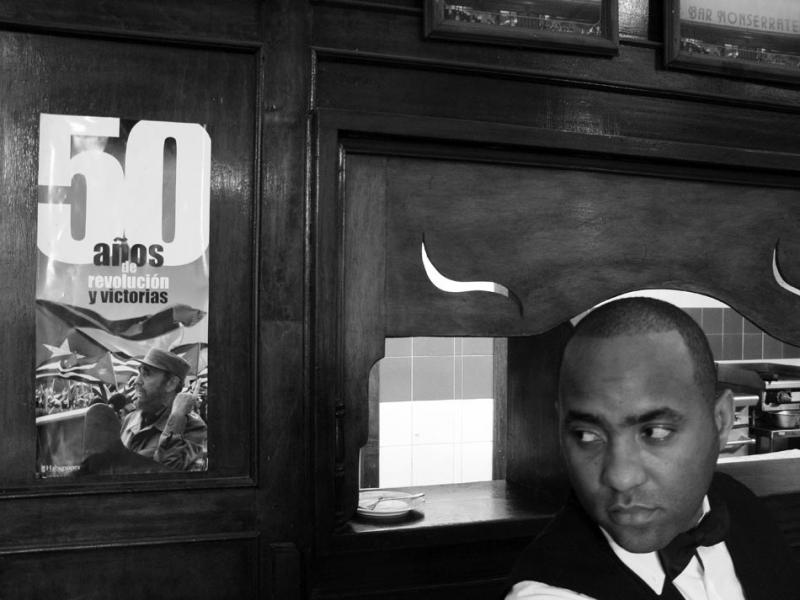

Signs near the barracks now carry slogans that read FROM MONCADA UNTIL TODAY, 50 YEARS OF VICTORIES! but in its early days, the Cuban revolution, like the American one, was mostly a record of failure. It is amazing it came off at all.

Spread over the landscape is a feeling of debt, a sense that even after fifty years there is still something owed.

The Moncada barracks now houses a school and a television station in its bright, sprawling bulk. There is also a museum, riddled with bullet holes. Only a few of them are real; the damage from Castro’s attack was repaired, most of the original holes filled in. After the revolution, the victors returned and remade the holes and Moncada assumed its place in the list of victories.

The evening has cooled and softened. Celia is too young to remember the revolution, but her aunt attended school in the barracks. One day, bored, the young woman and some friends pried into a boarded-up room and there in the dimness and dust they found old brown bloodstains. They had stumbled into a torture chamber, a leftover from the days before the revolution when the dictatorship had rounded up suspected enemies and hauled them to Moncada.

In the 1970s and ’80s, when Celia herself was a child, life improved in Cuba. With support from the Soviet Union, the nation modernized. Massive new apartment blocks appeared. Construction crews began work on a national highway running from one end of the slender nation to the other, carrying new Ladas imported from Russia.

Then, in 1991, the Soviet Union collapsed and its aid to Cuba stopped overnight. You can drive to the spot where the highway crews abandoned their work, the pavement running out in the dirt like water into sand. Worst of all, food vanished. Food rationing, always and still a feature of Cuban life, was tightened so children would have the most. People began eating tree rats. Life, the one thing Cubans truly possessed under socialism, seemed suddenly as though it was borrowed on shifting terms.

Everyone lost so much weight. People were skinny, skinny, skinny. Like “America’s Next Top Model”? That is too fat.

Cubans called it the periodo especial. Fidel told everyone that to keep Cuba and its revolution going they would all have to suffer. He didn’t say it like that, but that’s what everyone understood. They would suffer because without Soviet aid, Cuba was too poor and too isolated to do anything else.

Today Celia’s home is in Canada with a new husband and a new life that in its largeness and novelty includes snow—maybe a little too much of that. But her family remains in Cuba and she visits often. They are all old enough to remember.

She lifted the plantains from the spattering oil and slid them onto a paper towel, stains spreading. The rice was ready, the chicken. A simple meal: a feast nonetheless.

Oh, it depresses me to even talk about it. That’s why Cubans don’t drink very much. After two beers, they get depressed.

On the television, on all Cuban televisions, a short documentary appears. It reminds that the anniversary is coming. It reminds that the revolution has not ended; it never ends here. Like George Bush’s war on terror, the Cuban revolution is perpetual and senses its enemies everywhere. Life has improved since the periodo especial. But spread over the landscape is that feeling of debt, a sense that even after fifty years there is still something owed. That night, above the baseball and the dominoes and the dinner tables, the ghosts of struggle lingered.

We sat to eat. A red-checkered tablecloth. Water in the glasses had been boiled, then filtered. The food was warm and plentiful. Most people don’t eat the tree rats anymore. With Canadian dollars Celia and her husband have helped her family eat well. Three dollars buys sixty eggs, her husband said. He tried to send other friends in Cuba three hundred dollars per year, a dollar per day. It is close to the state-controlled annual salary of many Cubans. Celia started to speak, then stopped. She thought she had said too much, perhaps made statements too strong. She tried to dilute her words.

I love Cuba. I am 100 percent Cuban.

But she couldn’t quite do it.

The best thing I ever did was leave.

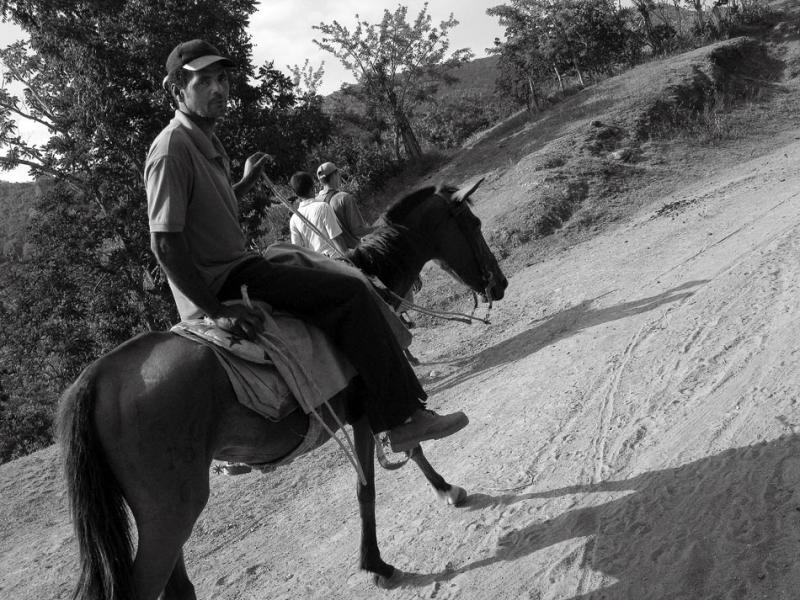

Far west of Santiago a dirt road rises from the coast into the mountains. The way is rough and busy with goats and cattle. A few enormous bulls, skin tight over racks of bones. Ahead, the first steeps of the Sierra Maestra, the mountain range where Fidel hid and directed the revolution, rise into the sun. The light is blinding. It washes out all depth and most of the color. There is only beige rock and flat green vegetation. The light pierces all.

Soon the pavement runs out into rutted dirt and the goats stop eating to seek shade. A few people pass on foot from distant villages, many wearing flip flops and not sweating at all. Sweat pours from me. A boy tells me he is descending to go to school in a town near the sea. He’ll stay there twenty-five days, return home for a few, then go back for another month of classes. There is a girl in jeans carrying an umbrella, a shirtless teen in shorts carrying nothing. I give him some water and he walks on into the light. Only two small jeeps will rattle past all day.

After a couple of hours walking alone, there is a sudden rustle, and a rider on horseback bursts from the roadside scrub. He is thin, wearing a blue shirt and blue pants and a straw hat decorated with the Cuban flag. The horse clomps up beside me; the man begins talking, and in a few minutes invites me to his house. It is a one-story clapboard rectangle topped with corrugated metal. The rooms are spare, dust and light wash through unhindered. Attached behind are rooms for cooking and storage. Pigs and chickens run out back. A litter of newborn puppies, eyes still shut, squeal in the shade of an old charcoal oven, and lining the edges of the yard, just before it plunges into a steep ravine, are the bones of past meals.

We have had coffee and are scooping into beans and rice before he asks my name. He introduces himself as Miguel, his wife as Roselena. Miguel works in the valley on a cooperative farm. Their son, Miguelito, also a farmer, is visiting with his one-year-old daughter. She chases the chickens and harasses the rib-thin mother of the puppies.

Miguelito is taller than his father and thinner. One of his eyes drifts lazily. He is interested to know my salary and how much things cost in the US—bicycles, cameras, houses. At each price his eyes widen. The numbers take root. It does not matter if there is a housing crisis, a falling dollar, or a deep recession—though he knows all about these problems. Many Cubans earn less than twenty dollars a month, and everything I name costs more than he makes. Some things cost more than a lifetime of work would earn. It is bewildering to see the limits of your life described in the possibilities open to others.

Fidel is never mentioned, there is no need to ask. He is present, in a large photograph set atop a glass-front cabinet in the house where Roselena, like many other Cubans, stores china and glasses, keepsakes, the best things. Like a bearded ancestor Fidel keeps watch over the bedrooms, notes the arrivals and departures. He is revered by campesinos, peasants, but also indebted to them. The quiet generosity they show me is what saved him as he struggled through these mountains, his clothes barely dry, while the soldiers of the dictator knocked on the doors and bombed the fields and found nothing.

The road drops into thicker forests. I hop boulders across shallow streams and pass a one-room school house, its yard fenced in white against wandering goats. On a downhill stretch another horseman reins up beside me. His name is Rogelio and he wears a machete on his belt. It claps against the dark brown pelt of the horse.

“How is life in Cuba?”

“Good enough, good enough,” he says.

“Many people want to leave, eh? Go live in the US?”

“Not me.” He smiles. “I live here, my life is here. You have a lot of snow up there. I’d die of cold!” He pinches his arm, emphasizing his point with the color of his skin. It is a creamy black. Elsewhere, light-skinned Cubans have pinched their own arms while explaining that negros is dangerous, untrustworthy.

Rogelio is tall and thin; he looks too big for the horse. His job in this remote place is to care for a one-kilometer stretch of the awful dirt road, filling the potholes, slashing the brush on the shoulders. Each kilometer has a custodian, he says. Rogelio also tends a small garden plot growing food for his family. He is just riding home from a nearby town, where he must travel regularly to fill out paperwork for his paycheck. The ride takes three hours each way. We go on in silence for a while. On the roadside, in the grass, a cluster of painted stones shout revolutionary slogans.

LONG LIVE FIDEL!

DOWN WITH BUSH!

50 MORE YEARS!

I mention the approaching anniversary.

“Ah, yes,” he says. “And we’re continuing forward!”

He grins and waves his arm toward the future.

“Seguimos adelante!”

We pass through the pueblo of Caridad de Mota. Kids playing baseball stop and stare after us. A handful of houses, small and brightly painted. Chickens and pigs root through the shade. Rogelio’s house is just outside the little center. The roof is corrugated metal, walls of thin boards. Inside there is one large open room with a concrete slab floor and a small sink in a corner. Two beds occupy the opposite corner beside bags of concrete. He is rebuilding the place, he says. It was flattened by the hurricane in 2005. Birds barnstorm the dim interior.

Rogelio’s wife, Marita, makes us sweet drinks with powdered sugar and brings me two small buns spread with garlic. Rogelio leans back against the wall in his chair. I learn that he fought in Angola, where Fidel once sent Cuban soldiers to support African rebels. He left for Africa in 1986, when he was nineteen, and like the others I have met, he shrugs at questions. The gesture of soldiers. They are the Vietnam veterans of Cuba.

“We didn’t have much food.”

“Why did you volunteer?”

“To help the people. They didn’t have liberty, they didn’t have anything. They were being repressed.”

In Iraq, American soldiers have told me the same things.

The afternoon drains away, the light retreating through pinholes in the roof. A single compact fluorescent bulb illuminates the house. In Cuba energy is part of the revolution and the government has mandated that all bulbs be switched to the energy-saving CFLs. There is a television and a small dining table. Water stored in jugs. His wife has decorated in small ways. A few dried flowers on the wall, a vase in a corner. Beside the TV a kind of curtain hangs, made from knotted candy wrappers. They are purple and green and all the colors of the rainbow. In the US, in my neighborhood, college students would pay one hundred dollars for it.

On television, we watch a program in which Cuban journalists tally the offenses of America and explain how the US funds counterrevolutionary activities in Cuba. The journalists produce e-mails, read through reports. They play wiretapped phone calls.

The imperialists are trying to destroy us.

They remove their glasses and shake fingers at the camera.

We must be ever vigilant.

And then the program ends.

Seguimos adelante en combate!

Rogelio watches and agrees. His accord is quiet, he doesn’t get upset. He merely believes, like many Cubans, that the US and the politically powerful Cuban community in Florida are relentless in their attempts to sabotage life on the island. It doesn’t matter if those attempts are aimed, as many exiles might say, at the socialist government of Cuba; Cubans like Rogelio take it personally. And why not? We have tried to assassinate Fidel. We launched the Bay of Pigs invasion. Whatever truth may hide behind this overheated program, those attacks haunt the Cuban conscience.

To look at Cuba, to really see it, requires acknowledgement of US policies in the region—the propping up of dictators, the instigation of rebellions, blindness to murder and massacre. The bizarre persistence of Cold War rhetoric. This is one reason most Americans don’t look at all: Cuba reveals too much. I glance around the room. One bulb, one television. That there is electricity here is due to Fidel, who electrified these regions after the revolution. Before it, under Fulgencio Batista, there was poverty and illiteracy and disease. Fidel was not inevitable, but change was. The US gambled wrong. As we have learned elsewhere in the world—in the slums of Baghdad, for example, where Shiites living in sewage-smeared neighborhoods without water or electricity rose up against US troops—it does not take much for miserable people to fight, to reach for something.

Cuba and the US share the need to learn this lesson. Rogelio, a veteran and patriot, seems satisfied. Who knows? In the countryside the Cuban government enjoys deep support. But even now thousands, perhaps millions, of people look to the sea and dream of leaving.

Rogelio asks if I would like to stay the night. I am exhausted, caked in sweat from walking. Dried salt rubs into my shoulders.

“Thank you.”

“Of course. When you go home you’ll have to say that in Cuba, in the mountains, a black man took care of you.”

I fall asleep beneath a white mosquito net, in a bed beside the one Rogelio shares with Marita. The night is soft and cool. There is the distant laughter of children. Frogs in the forest transform the night into a long, singular vibration. In the morning Rogelio puts on his pants first and second he puts on his machete. Marita feeds me leftover soup and fills my water bottle. The couple stands silently in their yard, slightly apart, watching as I walk up the road.

Many hours later I descend from the mountains past plaques that commemorate battles where Raúl lead men against the dictator. I am falling asleep on my feet. From a listing farmhouse on a hill a pair of dogs flies at me, teeth bared and gleaming. Their feet whisper in the grass. I must pelt them with stones to keep them away. It is an awful feeling.

“Oh, no.” The old man’s entire face slumps. “Look, I have tits!”

As if it were my fault. He frowns at the digital camera, at me. He is shirtless, sitting on a chair outside his door in the southwestern city of Bayamo. Across his brown, sagging, seventy-five-year-old chest spreads a large green tattoo, faded from the sun, the cigarettes, the years. He got it in Angola, while fighting for Fidel when Fidel was sending revolution to places that were apparently even hotter than here. I drip beside him. I can’t believe it is hotter anywhere but the sun.

“Oh!” He dismisses the idea. “So hot. It was terrible.”

Across the cobblestone street, Cubans worship in an old Catholic church. Their murmurs slip over the stones. Children kick a deflated ball across the steps and squeal, chasing it. The man leans back and demonstrates how the tattoo was made, with a knife blade, by pricking at his chest.

“We ate elephants, you know,” he says, looking at the sky. “The skin was very tough. You wouldn’t believe it. Elephants!”

We sit talking. A teenage girl standing near rolls her eyes with every story the old man tells. She circles her temple with a finger. He’s crazy. She is his granddaughter, and she’s tired of his rambling.

Across the wide shadow of the church a young man comes carrying three fish tied through their gills and mouths with a frayed rope. He is the old man’s son, the girl’s father. He joins the conversation and soon they’re laughing at the veteran, telling me he returned home from Angola after only nine months. The shooting and violence and explosions were too much.

“He’s a coward!” the son says. The old man agrees and waves his hand, pushing it away.

“Basta,” he says. “Enough.”

They ask questions about the US. At first, it is about how much things cost. Then they complain about George Bush, and ask me to explain the war in Iraq. When they hear I have been to Iraq as a journalist they stop asking. Talk shifts to the US embargo. Why do you still blockade Cuba? It makes no sense to them; it is impossible to defend. The embargo cripples Cuba’s economy. It stains all aspects of life.

“You did it to hurt Fidel,” the son says. “But it hasn’t hurt him. It’s hurt us. Why can’t you see that?”

The blockade is not so different from the sanctions imposed on Iraq in the 1990s. They, too, were designed to hurt the leader, Saddam, another villain we call by first name. Those sanctions did little to shake Saddam’s reign. Half a century of blockade hasn’t changed Fidel much either, and he is no Saddam. It occurs to me how easily we treat countries with worse records than Cuba’s, or ones we have openly warred against—China, Russia, Vietnam, North Korea. No other small nation drives us to such froth and sputter.

The soccer ball thumps against the church steps. Candles flicker inside and there is a scent of incense. Daylight falls away as swallows drop from the bell tower and streak over the red-tile rooftops. Enduring things.

“What about America,” the girl asks. “Isn’t it really violent?”

Her father points at the soccer game.

“It’s not safe to go out on the streets at night, right? You will get shot or stabbed. Children cannot walk on the streets alone, right?”

It’s something I hear often, an idea fed by state-run TV. I tell them I walk through my city every night with no trouble. Their heads tilt, as if I had stopped speaking Spanish.

“Really? That’s not what we heard.”

Cubans are proud. They remember how they repulsed the invasion at the Bay of Pigs. They remember how they sent troops like the old man to fight alongside African rebels in the ’70s and ’80s. Their nation was once considered the most advanced in Latin America. Vanished days. But when they compare themselves to the US—they do it without prompting—Cubans speak haughtily of their education system, still the envy of many countries, and their health care system, which is free to all. Earlier, the son recalled how Cuba offered to send doctors to New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. The US government—flailing, confused, and inept—mustered enough attention to refuse.

In Cuba, education and medicine form two legs in a sort of pedestal of nationalism; the third leg is domestic tranquility, another area where Cubans believe they trump Americans. I have just kicked out that leg. The pedestal wobbles. It cannot be true. The son says goodbye and carries his fish inside. His daughter follows, leaving the old veteran and me watching stars glimmer above the church.

“You should come live in Cuba,” he says. “It’s very peaceful here.”

He slips on a threadbare shirt, doesn’t bother with the buttons.

“Well, I’m here every day. If you’re still in town tomorrow, come by.”

He turns and slowly moves into the dim hallway. I can see a bed and some shelves. The sounds of dinner, pouring water. He pauses, and turns just slightly.

“Elephants!” he says, and is gone.

The chief of Police Sector 2 leads me to a small room, points to a broken chair, and seats himself at a desk. He sets a sheet of paper on its battered top and places my passport beside it. The paper contains a list of numbers and names. I cannot see if mine is there. He wears a gray T-shirt and jeans, metal-framed glasses, the shadow of a goatee. A smile. We begin.

How long have you been in Cuba?

Some of the questions he asks twice and from different angles, a cop’s technique. Some of the answers he writes down. He picks up my digital camera and asks how to erase. He scrolls through the photos, selecting, frowning, deleting. It takes a long time.

Why were you taking so many photos?

His smile has vanished. The walls are gray with grit and scratched. Behind the chief is a boot print at head height, as if someone had tried to kick through. Behind me is Fidel. He stares down from a photograph, his head slightly cocked, as though he were listening. Maybe he is the good cop.

I had been walking in Camagüey, a city in the central part of the island, and I’d stopped to watch a crowd outside a store. Perhaps sixty, seventy people. Every few minutes the shop door would open and a few would squeeze inside. The rest would lurch forward, hands pressing the glass. I asked a young man what everyone was waiting for.

“To buy lamps,” he said. He shaped one in the air with his hands. “Very nice.”

“Why the big line?”

He laughed. “That’s Cuba.”

I imagined something necessary, practical. The man shuffled away and returned with a friend who cradled a lamp in her arms. It was small, plastic, hideous. The rectangular base was painted silver and from the top sprouted a bright blue umbrella lampshade. In the center of the base was a clock.

“Isn’t it great?” she beamed.

Heat like the fevers of childhood, the crowd swelling. The shop door opened, a few went in, a few came out carrying three, four lamps. The idea, the man said, was to buy as many as possible for about three dollars and then sell them again for five—almost one third of a monthly wage. Around the corner, I watched hurried transactions as those with lamps were mobbed by those with desire.

The crowd grew agitated. A sense that supplies were running out. Soon a woman was yelling, with more joining in. Hands pounded on the door and people began shoving. Across the street a crowd had formed to watch the crowd. A few policemen arrived and divided the line in two. Waiting in line is important in Cuba; you get used to it quickly. There are certain unbreakable rules. The police destroyed that order when they reshaped the line, and a wave of sweaty bodies wrestled for new places. I shot photos until a tall cop noticed.

“You,” he said. “Over here.”

At the police station, I sat waiting beside a reception desk where an old, wrinkled woman answered a phone and waved at flies. The station was disintegrating. The doors are high and heavy, the doors of ancient Spanish cities, studded with bolts. A smell of urine. I waited for an hour. The chief arrived looking as if he’d been summoned from his day off. He led me into this backroom.

It is all polite. The chief lectures as he deletes, stopping now and then to look up from the camera for emphasis. Those Cubans in Miami—the Cuban Mafia—they want to kill Fidel. Imagine if we sat here and plotted to kill Bush.

He covers many topics.

Have you seen Michael Moore’s movie, Fahrenheit 911? There is no way a plane crashed into the Pentagon. Where was the wreckage?

He reaches certain conclusions.

You say you want to give us freedom. But we already have it. Cubans, you see, have more freedom than Americans.

I ask why photography is illegal.

It isn’t. But you might use those pictures to harm Cuba. Americans have bad ideas about Cuba. You think we are all so poor, that we have no food. We have plenty of food. See?

He lifts his T-shirt and slaps his big, brown belly. I think of Celia, in Santiago, and wonder if this man was ever skinny, skinny, skinny.

Cubans, especially those in official positions, are very concerned about how their country appears to the rest of the world. Not unlike the Chinese. They want the world to believe their system works. And he is correct, to a point. Most Americans have only bad ideas, and a handful of words, to describe Cuba.

Cubans are wonderful people. They would take you in and give you water, feed you. It is a beautiful country.

I tell him crowds also form outside stores in the US on the day after Thanksgiving, or when new cell phones and video games debut. He isn’t interested. We are not having a conversation. When he is done deleting he looks through my notebook, then he stands and returns the camera. He tells me his name is Fred.2

If you had been doing this in Havana, they would have thrown you out of Cuba.

The message is clear. He pats me on the shoulder and points to the door and tells me he will Google me later. On a table against the back wall of the room there is a small, familiar box. Inside it is one of the lamps.

The rental jeep is red as a Communist star and mine for four days. There are three seats and a small slot for luggage, sacks of fruit, piglets. I set myself a quota: at least fifty hitchhikers, one for every year of the revolution. Judging by the crowds rimming the roads, clotting at intersections, it will be easy. Hitchhiking is a national pastime in Cuba—like waiting in lines—because the transportation system is so bad there is often no other way to get around.

Saturday, noon. Three minutes out of the rental lot I pick up the first passenger. She stands in the heat by an empty traffic circle. All the roads are empty. She is twenty-seven, a single mother heading home from work at a cafeteria at the provincial university in Camagüey. We drive perhaps two miles to the small apartment she rents. Technically renting an apartment is illegal; in Cuba housing is supposed to be free. But there isn’t much housing, and Cubans are mostly expected to stay put where they live or endure enormous trials of bureaucracy and bribery in order to move. Without permission, without family, my passenger fled her rural hometown and now pays black market rent to stay quietly under the radar.

She signs my notebook.

“What’ll you do with the rest of your day?”

“Watch TV,” she says. “What else is there to do?”

She blows me a kiss goodbye.

Three minutes, another passenger, an eighteen-year-old military academy cadet, hitching home for the weekend to do laundry. He daydreams about the future.

“It would be great to be a military investigator,” he says. “If I can’t do that, I’ll join the navy. The military pays pretty good.”

Two minutes, two more passengers, and the jeep is full. They squeeze into the back, a middle-aged truck driver and a prison guard in his early thirties. We fly past cows on the roadside. Past other, disappointed hitchhikers. We talk baseball and Obama on the way to a town called Florida. Can a black man become president? The idea has them giddy.

At home I sometimes hear stories of hitching in the 1960s. Buckets of pills passed around in backseats, clumps of hippies waiting at the entrance ramps to the highways. My uncle hitched across the country. My dad thumbed rides back and forth to college and later, as a young father, to work. That America is dead, but in Cuba it lasts. Grandmothers wave for rides at the entrance ramps, and the only drug is rum.

Leaving Cayo Coco, a sunbaked mangrove key on the northeast coast that is home to a dozen tourist resorts, I pick up three young guys. Two work in construction, building more resorts for the crowds of Canadians and Germans, turning Cayo Coco into Key Largo. They are migrant workers in their own country, slipping illegally from the country to the jobs. We talk about Raúl Castro, Fidel’s younger brother, who now runs the country.

So far Raúl has stayed the course, and, occasionally, allowed Cubans to acquire more stuff—cell phones, personal computers, those terrible lamps. During my visit the curious ban on owning microwaves is lifted, and Chinese refrigerators are arriving in bulk. Large trucks hurry them to those who can pay while the old Russian refrigerators are removed, artifacts of failure, and shipped back to China for recycling.

Fidel is brilliant—he has huge balls—but sometimes his ideas got in the way.

The Museum of the Revolution in Havana displays many black-and-white photos of the rebel army. In a lot of them Fidel looks into the distance, thoughtful, serious. Watching for the future’s arrival. Raúl almost never looks that way. In most of the old photos I have seen he is grinning, a thin young man, a boy, really, who, in the way of little brothers, simply looks happy to be included. I was surprised when I noticed that beneath his revolutionary beret he wore his hair in a long, dark ponytail. A mane to Fidel’s beard.

When I asked a museum docent about the contrast between the Castros, she smiled and shrugged and shook her head.

“Raúl was just a baby back then,” she said. He had no idea what was happening!

But that is not true. The journalist Volker Skierka writes in his biography of Fidel that after the victory it was Raúl and Che Guevara who pushed the executions of prisoners, while Fidel may have worried it was going too far. Raúl was also a hard-line Communist while Fidel, in the beginning, openly fought with Cuban Communist party members and seemed willing to look for another path. Most of this seems forgotten, if it was ever widely known, and now the younger brother rules. The young men in my jeep like him immensely.

He’s more practical. Fidel is brilliant—he has huge balls—but sometimes his ideas got in the way. Raúl is more direct.

Raúl will change more things. Under him, life could improve.

But it’ll still be mostly the same.

There are few streetlights. Bicycles and horse carts loom in the darkness, no reflectors or lamps. Night doesn’t stop this kind of traffic. Most of the passengers talk, one young woman sings to herself. Some are silent and empty, as if weariness and heat had worn out all the words. Hitching is exhausting; life runs out in the waiting.

I pick up Cuba. A doctor, a boxer, coffee farmers, a trio of drunken lumberjacks. A soldier and speech teacher dressed like hipsters and headed to carnival. A twenty-seven-year-old bio-tech lab technician named Eva argues with an older woman about whether Cubans are truly free. She thinks not; she wants reform. She would like a car—just a small one. It would help her keep up with a world she feels leaving her behind. No thank you, says the other woman. She is perhaps forty-five and thinks the world possesses little worth envying. They bicker, generations pulling apart like continents. Eventually they agree that they are, sort of, free.

“We’re free to talk about politics,” Eva says. “We’re doing it now, aren’t we?”

“Yes,” the old woman says. “See?”

They are really asking each other.

Cane fields to the horizon, the light pouring down. Empty baseball stadiums. Tall stacks of sugar mills dumping black smoke into the sky, or silent and dead as stumps because the sugar industry is in ruins. From the dark woods on the roadsides farmers emerge selling luminous rounds cheese. For a brief time I am passengerless. I floor it. A city disappears behind in dusk and thunderclouds. I round a corner and there on the sidewalk stand half a dozen cops in blue and gray. Dread blows through me, like hitting a speed trap back home.

One of them steps into the road. His arm shoots out.

Fucking Fred has called them, I know it. He told them I was headed this way.

I pull over. He walks up, hands looped through his gun belt, the others staring behind him. He is smiling.

“Where are you going?”

I point out a tiny town on the map.

He shrugs.

“A shame. We’re all going to Havana.”

Tomorrow is Monday, after all, and Havana is six hours away. In the rearview, he is waving.

On the roadsides the billboards do not advertise products, they sell revolution.

REVOLUTION IS: MODESTY AND INTELLIGENCE!

The slogans are repeated on the sides of houses, bridge underpasses, those stones in the grass, all across the country. They answer my questions. I might wonder, What is revolution? Around the next corner the answer, painted on a low garden wall:

REVOLUTION IS: FIDEL!

Cuban instant messaging. Ubiquitous as Fidel’s image and broadcasting the conclusions of a one-sided debate. It is almost as though the slogans are answering each other.

REVOLUTION IS: FOREVER!

One of my last hitchhikers is Roberto, a twenty-eight-year-old medical imaging specialist. He stands at a small-town intersection wearing a white lab coat and a camouflage baseball cap with a US Air Force patch. I take him and his girlfriend, Sara, to Santa Clara, where Sara lives with her mother. The city was the final battleground of the revolution. Che Guevara and an equally dashing and doomed rebel named Camilo Cienfuegos captured the city on December 31, 1958. The next day, in the blackness before dawn, Fulgencio Batista, the dictator, fled in a plane to the Dominican Republic. By embezzlement and simple theft, he had secured himself a fortune worth perhaps $300 million.

Roberto is 28, tall and handsome, with thick black hair and a few days’ scruff. A dimpled chin. Sara is 35. She has a wide, easy smile and dark curly hair. She was married once, to an Italian, but he died a few years ago. They take me to see Che’s mausoleum. He was killed in 1968 in Bolivia while trying to export revolution, but his body was eventually returned to Santa Clara. We walk through the city center, the old green hotel still flecked with bullet holes (real ones, this time) from Che’s attack. Across the main square, Roberto and Sara enter an electronic shop and Roberto guides me through the component parts of the computer he dreams of building. He could never afford it; my presence reminds him of that. He points to a 4-gigabyte flash drive, it costs a little over $80 US dollars.

“If I worked for six months, and didn’t eat, or buy anything else, I could get that,” he says, sighing. “Look, Fidel is great. He is one of the most magnificent men on the planet. But he can’t do everything by himself.”

He leans against the glass. Sara sidles up to him and strokes his arm. They stare into the case for a long time.

For Roberto, the approaching anniversary of victory and socialism doesn’t mean much. Sara agrees, but less adamantly. She simply wants to travel. International travel for Cubans is technically legal. But the process deters most from going anywhere. Heaps of paperwork, thickets of permissions. An invitation must be obtained from the host country. And the sheer expense—years of saving would be necessary. She tells me she would go to Italy, to see her husband’s grave.

Later, in a small, third-floor apartment, we drink coffee and eat cake as a thunderstorm washes over the city. Brown birds dart through the open windows. In the distance, above Che’s mausoleum, enormous floodlights blaze to life.

Sara’s mother, Lola, is fifty-six, a retired teacher. She is blue-eyed and wears a green tank top and sits on the cool tile floor, a thimble of sugary coffee in her hand. She begins telling me about the revolution and growing up right after. I ask if it can go on forever.

“Yes,” she says, and starts to explain. A teacher’s soft insistence.

Roberto rolls his eyes.

“Everyone her age thinks the same,” he says. “My dad is like that too, a total socialist.”

Sara glares at him.

“You wouldn’t believe how it used to be, before the revolution. My family told stories.”

Her voice rises. Something has been scratched open. They have fought over this ground before.

“I am a socialist, through and through,” she says. “In other parts of the world—in Latin America—children go hungry or they can’t go to school because they can’t pay. In Cuba it’s not like that.”

“But we can’t live!” Roberto says. “We can’t afford to buy things. Me, for example. I can barely afford to buy soap that’s made here. In my country. It’s not that I want a lot, or I want to live like an American. I just want a normal life.”

Lola grows angry. For her, normal is now, the present tense of Cuba. The argument escalates. Sara disappears into another room. Roberto and Lola talk over each other, they begin shouting. Rain splatters through the windows.

“We lived through those tough times. You didn’t, you weren’t alive. We have normal lives. We have freedom.”

“But it isn’t like that!”

“Shut your mouth. Yes it is.”

“No.” He smirks, then smiles broadly. Infuriating things.

“Lies.” She turns to me, red-faced and shaking. “Not all young people are like him.”

He laughs. “But all old people are like her!”

The storm passes. I follow the rain out of Santa Clara. When the city fell to the rebels, Fidel was hundreds of miles south, in Santiago. Upon news of Che’s triumph, the comandante headed north on a victory tour, and a week later cheering crowds lined the roadsides as he entered Havana. Today, soaked hitchhikers stoop along the roadsides. I stop at an intersection and several run to the jeep, there isn’t enough room for them all. In the end I pick up fifty-three over four days, but I am not there yet. We head west. All around us billboards shout into the dusk-stained sky. To the left, rising from the cane, the best of them. VENCEREMOS! it says. We will win!