The cracks of gunfire echoed down Highway 1, then there was silence. The moon had yet to appear over Kandahar and the night was black. I hurried to the Unit Medical Station (UMS), a frontline army hospital at the forward operating base (FOB) where I had spent so many days watching broken bodies roll in. It was the peak of the Afghan fighting season, a time in late summer when all the perfect conditions for war come terribly together. The medics stood outside the UMS, like they had all summer long, waiting for the casualties. No one said a word; they knew well the horrors that would be coming.

Finally, the silence was broken by the sound of a vehicle racing toward us in the dark. Taliban insurgents had ambushed the Afghan army, resulting in a hit-and-run firefight. The wounded arrived in bullet-riddled vehicles and were put on stretchers and brought into the UMS. A single doctor worked through crowds of medics and soldiers, feverishly bandaging shredded bodies. Several Afghan soldiers had been wounded but would live; a helicopter medevac was called in from Kandahar Airfield. When all the soldiers had been treated and evacuated, another casualty arrived in the dark, a civilian, a young man shot multiple times in the abdomen.

There was so much blood I could smell it; I still can. He was pale, barely twenty. It was an incredible struggle as the doctor plugged tubes and instruments into the young man to keep him alive. Emotions ran high as hope that he would live, even with such severe wounds, filled the air. “C’mon, hang on!” yelled the doctor. Medics shouted for instruments. The doctor gave orders. They all yelled to the man that he would make it. He was brought back from the edge of death several times; at one critical point the doctor managed to contain a massive wound on his left side and stabilize him. But his body couldn’t hold on. He shook a few times, and then lay still, eyes wide open, gone. The doctor screamed in frustration, threw a tube on the floor, and turned away. Then she turned back to look at the dead man staring up to the ceiling. A medic walked up, placed his hand on the young man’s eyes and closed them, and held his hand there, staring at him for a moment. I had lost track of how many bodies I had seen come through there. It had been a brutal summer, with hundreds of Afghans leaving their blood on that floor.

I began my journey into southern Afghanistan in 2006, when Kandahar City was in the midst of a wave of suicide bombings, marking the beginning of the downward spiral we remain in. In four years, I have seen Afghanistan in all its ironies—its beauty and its brutality. Sitting in a helicopter and looking past the barrel of the rear ramp machine gunner, all sound dampened to a hum by the deafening rotor blades, the mysterious and mesmerizing landscape unfolds below, its mountains and green lowlands shadowing the rivers. But when the bird hits the ground and you walk out past the chopping air and the thump thump thump of the helicopter disappears, the reality of this harsh and poor land becomes clear.

Every village seems torn from some lost apocalyptic book of the Bible. The land is barren, everything has been ravaged, and the people here literally have nothing to lose. They are, for the most part, illiterate; many do not even know their own age. They have no toilets, no electricity, and virtually all live in mud-walled homes. The only water is drawn from a well or a polluted river. The ground in many parts of the country is poorly suited to agriculture, but it is ideal for guerilla warfare. Such villages are where this war is being fought, and near-constant violence has made them all but inaccessible to journalists not embedded with the military.

So I decided to venture into some of the most remote combat outposts in the South, to see and experience the war firsthand for extended periods of time. I wanted to document the conflict as it played out in the most problematic civilian areas. I started in Zhari and Panjwai Districts, where Mullah Omar gave birth to the Taliban movement; then moved through Garmsir, in the heart of opium country; and into Farah, where Alexander the Great built a citadel in the fourth century BCE and where the violence recently had escalated. I went on scores of patrols and combat missions.

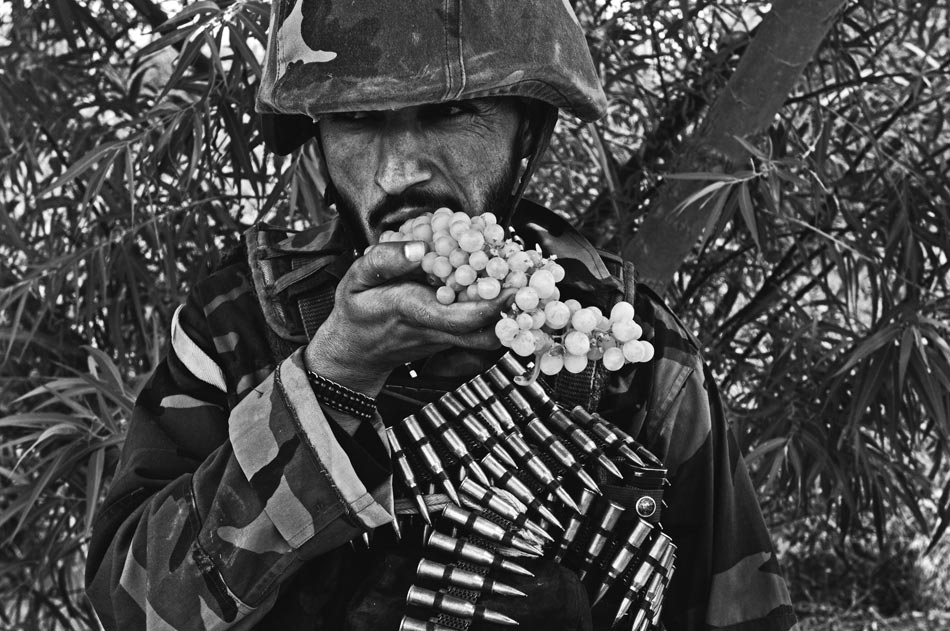

Finally, last fall, I traveled northwest by helicopter over spectacular mountain ranges to FOB Golestan, where I joined a company of US Marines. The weather was a welcome respite from the green inferno of Kandahar and Helmand, where I had spent months in 120-degree heat, wading through tall grass, rivers, and grape fields, nearly always under fire. Within a day of reaching FOB Golestan, I accompanied a group of Marines south, past the Buji Bhast Pass and beyond the Black Pass. It was supposed to be a quick two-day operation undertaken by ten vehicles.

Everything seemed fine at first. It always does. On day two, the Marines were starting to clear some areas and check for insurgent fighting positions in the mountains. On our way back to the FOB, the lead vehicle, an MRAP (Mine Resistant Ambushed Protected vehicle), hit an IED and was destroyed. There were some minor injuries; luckily no one was killed—but we were stuck there for the night. With darkness approaching, the Marines defensively circled the Humvees. The once-spectacular mountains now darkened and turned ominous in the creeping shadows of nightfall. The sun disappeared and no moon came up.

Hours passed and we finally closed our eyes. Then the shrieking whistle of a rocket passed by the rear of our vehicle and shattered the ground just beyond us. My eyes popped open to the white flash of the explosion. Incoming machine-gun fire and tracers lit up the ground all around us, then I felt a massive weight on me and couldn’t breathe, couldn’t move; a Marine had leapt out of the way and on top of me. Machine-gun fire tore at the ground beside us, and we rolled over to the Humvee doors for cover. The firefight went on for another half hour. Thousands of machine-gun and mortar rounds echoed through the mountain passes like a roaring monster. Fear and loathing in the Black Pass and no way out.

As morning broke, we tried to move, but in every direction our vehicles hit IEDs. There seemed to be no safe exit, and now we were afraid even to walk around. Days passed as help tried to reach us, only to hit more IEDs. The unit decided to move through a riverbed, tossing explosives ahead of the vehicles. Just when we seemed out of danger, cracks of gunfire rained down on us from the mountains above. I realized that my Humvee was not even the new up-armored model. Fearing a mortar or RPG, I jumped out and ran behind Marines rushing forward for the fight. They fought through the village of Gund and finally pushed out of the valley.

Hours later, when we got back to the FOB, I stumbled to my tent and lay down with relief while the bomb-sniffing dog, a black lab named Boss, licked my face. I caressed him and stared over at the empty bunk of a Marine who had been injured in one of the IED strikes, until I passed out in exhaustion.

The Black Pass broke me. When I opened my crusty eyes, I lay looking out the tent door flapping gently in the cool mountain breeze and realized that I had to get the hell out of Dodge. I couldn’t see an end to what I’d been covering, and the risks no longer made sense. Afghanistan is like a balloon. If you squeeze one end, it just swells on the other. People always ask me broad policy questions—most of all, how the US can win in Afghanistan. After four years there, I’m forced to ask: what is there to win? For every five or fifty or five hundred weapons captured, replacements always arrive. For every insurgent killed, more spring up. And yet, there’s no denying that, from what I’ve witnessed firsthand, a Western military withdrawal would almost certainly mean civil war—and far more killing than we are seeing now.

Which reminds me of an Afghan interpreter of Tajik ethnicity I befriended deep in the desolate mud-walled moonscape of the green zone of Panjwai, outside Kandahar City. He had been around fighting all his life and could find and reveal an insurgent’s weapons cache just by scanning the contours of the ground. Over hundreds of glasses of steaming tea and packs of Pine-brand cigarettes from Pakistan, we talked for hours at the FOB and many times in the field during combat operations. One night, we lay back in the dirt staring up at the sky. He spoke of the time when NATO forces would leave and Afghan militias would stream down to confront the Taliban. He explained that they would not be concerned about killing civilians, that massacre would be the only way, total war if necessary. If insurgents took refuge in a village, then the militias would shell the whole village. They would level everything if they had to, if that’s what it took to finally kill all the Taliban. The deaths of thousands of innocents would be accepted as a necessary part of such total war.

And rebuilding the country? Well, that never came up.