Through you I shall be born again; myself again and again; myself without others; myself with a tomb; myself beyond death. I imagine you taking my name; I imagine you saying “myself myself” again and again. And suddenly there will be no blue sky or sun or shape of anything without that simple utterance.

…

Sometimes when I wander in these woods whose prince I am, I hear a voice and know that I am not alone.

…

Solemn truths! Lucid inescapable foolishness! None of that for me. To be the salt of Walt, ocean in osteality! … The fruit of the tomb! The flute of the tomb! The loot of gloom!

These words do not hail from the mouth of Walt Whitman directly. They are the words of one of his most astute heirs and readers: Mark Strand. Or rather, they are the words of a book called The Monument, Strand’s monument to the egotistical sublime. They are the words of poetry spoken in prose. Or rather, they are the words of the poet’s “translator in the future,” through whose hands the poet’s prose appears to have passed before reaching us, his readers. That translator, and we readers, thus find ourselves conjured into perpetual service at the votive flame of one who channels the one who aspired to have changed forever the possibilities of poetic speech. The satire is a little wicked, but the conceit is penetrating.

Walt Whitman did change forever the possibilities of American poetic speech: he enabled American poetry to leap quite over the Victoriana that so beautifully elaborated, and stultified, English lyric production right into the thick of the First World War. In The Monument, Strand is not merely burlesquing Whitman—and who could possibly outdo the poet himself on the scale of outrageousness?—he is dissecting the central rhetorical vehicle of Whitman’s art: the self so large, so exemplary, so all-encompassing that it empties itself of all specific content and becomes tautology. This despite the epic catalogues—full to bursting with bodies and place names and bustle and tools of the many trades—that constitute Whitman’s other most-often-resorted-to device.

The Civil War marked a dramatic turning point in Whitman’s poetry as in his life. The grandiosity and over-inflation, the heady idealizations of manual labor by one who preferred to “loaf,” all this encountered a terrific dose of reality in the regimental encampments of Virginia and the hospital wards of wartime Washington, DC. Drum-Taps, bravely, foolishly, wonderfully, records the double consciousness, the no-holds-barred before and after: both the thumping boosterism of “Beat! Beat! Drums,” “First O Songs for a Prelude,” and “Song of the Banner at Daybreak” and the utterly different portraits of “A Sign in Camp in the Daybreak Gray and Dim,” “Cavalry Crossing a Ford,” and “Bivouac on a Mountain Side,” poems suddenly shocked into sobriety, plain denotation, and, utterly new to Whitman, understatement.

Three forms I see on stretchers lying, brought out there untended lying,

Over each the blanket spread, ample brownish woolen blanket,

Gray and heavy blanket, folding, covering all.

(“A Sight in Camp in the Daybreak Gray and Dim”)

The sentences are simpler and shorter in these newer poems. The images are local— ”the bandages, water, and sponge”—before they are required to be exemplary. Some of the poems themselves are only four or five or six lines long.

A less confident poet might have tried to suppress the evidence of those earlier, ignorant calls-to-war. A less confident man might have tried to over-explain. But only a single poem in Drum-Taps, “The Wound-Dresser,” allows itself a revisionary backward look:

(Arous’d and angry, I’d thought to beat the alarum, and urge relentless war,

But soon my fingers fail’d me, my face droop’d and I resign’d myself

To sit by the wounded and soothe them, or silently watch the dead:) …

Of those armies so rapid so wondrous what saw you to tell us?

What stays with you latest and deepest? …

I dress the perforated shoulder, the foot with the bullet-wound,

Cleanse the one with a gnawing and putrid gangrene, so sickening, so offensive,

While the attendant stands behind aside me holding the tray and pail.

Aroused and angry he had been, in 1861, at the breaking of the union and the firing on Fort Sumter. But he had also been an enthusiastic supporter of the War with Mexico fifteen years earlier, the war of U.S. aggression that so horrified Emerson and James Russell Lowell. Until he spent those harrowing months attending to the wounded in Washington, Whitman saw militarism as a great tonic antidote to everything that afflicted American manhood, especially the debilitating absorption in commerce, or getting and spending.

The mythology that grew up around Walt Whitman, both during his lifetime and in subsequent eras, has invested heavily in the intertwining of life and work. He was the great visionary of democracy and emancipation, and is credited, with reason, for instinctive recoil against slavery. But he was never an abolitionist, despite his reverence for Lincoln: in the pages of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, he excoriated abolitionists as “foolish red-hot fanatics” and abolitionism as “impracticable” and “wild.” He had written in his notebooks:

I am the poet of slaves and of the masters of slaves

I go with the slaves of the earth equally with the masters

And I will stand between the masters and the slaves,

Entering into both so that both shall understand me alike.

But in the Brooklyn Daily Times he wrote: “Who believes that Whites and Blacks can ever amalgamate in America? Or who wishes it to happen? Nature has set an impassable seal against it. Besides, is not America for the Whites? And is it not better so?” We like to think that Whitman’s heart was better than his head for politics, that, in the brother-to-brother encounter, his extraordinary aptitude for natural sympathy was a touchstone to be relied upon. But here is what he writes about watching the soldiers of the First Regiment, U.S. Colored Troops, receive their pay: “Occasionally, but not often, there are some thoroughly African physiognomies, very black in color, large protruding lips, low forehead, etc. But I have to say that I do not see one utterly revolting face.” And when, the following spring, he watched five black regiments march in review with the rest of Burnside’s army, “It looked funny,” he wrote, “to see the President standing with his hat off to them just the same as the rest.” Compare this to the “polish’d and perfect limbs” of the laboring Negro in “Song of Myself.”

Why rehearse these painful anomalies in an extraordinary writer’s extraordinary affective and cognitive embrace? We are all historical actors: the insights and assumptions that constitute our own moral bearing will surely, a hundred years from now, be found severely wanting, will produce some shudders in even those who wish our memories well. Whitman’s editorials on race and his casual comments on the black Union regiments bitterly disappoint us, wound us even, and their power to wound is fresh. I mention them because they shock us into thinking, once again, about what it means to read historically. I mention them because I struggle with them myself as I try to read Walt Whitman and understand his place in America’s imagination of itself. I mention them because, once again, the poets of America, or many of them, are struggling with what it means to speak both of and beyond the self, to write, in other words, politically.

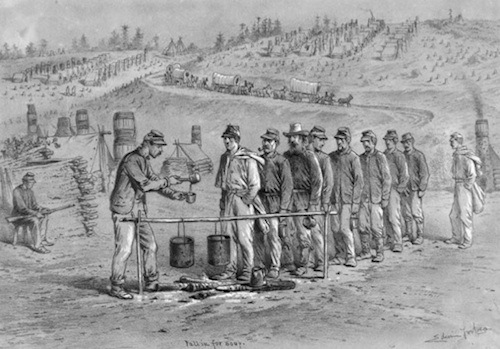

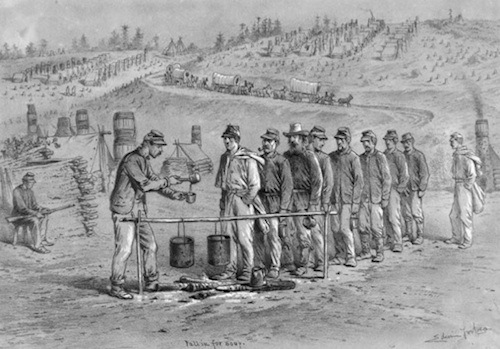

- “Fall in for soup,” a pencil drawing by Edwin Forbes, December 1862. Walt Whitman is third in line. Charles E. Feinberg Collection, Library of Congress)

Whitman’s aestheticizations—magnanimous and conflicted, encompassing and appropriative, visionary and vicarious in equal measure—are always, in Michael Warner’s wonderful phrase, the products of a “richly disorganized consciousness.” Nowhere, perhaps, is that rich disorganization more vividly manifested than in the poet’s visitations at the bedsides of working-class young men and soldiers. These began when he was still in New York and hitching rides with omnibus drivers. Visiting the ill and injured men in Broadway Hospital, he catalogued their afflictions in a series of articles for the New York Leader: fractured bones and amputations, gunshot wounds, burns and scaldings, rheumatism, typhoid, bronchitis, consumption, delirium tremens, dysentery, pneumonia, opium overdose. After war had been declared, Broadway Hospital began to fill up with soldiers who had joined their regiments in New York only to be felled by a measles epidemic. Subsequently, of course, Whitman’s ministrations to the ill and wounded in Washington’s wartime hospitals became the defining experience of his life in the nation’s capital. He assisted at surgeries, brought gifts of jelly and tobacco, socks and shirts, read to the patients, wrote letters for them, fed them, fanned them, sat with them in their death throes. He had written: “I believe a leaf of grass is no less than the journeywork of the stars, / And the pismire is equally perfect, and a grain of sand, and the egg of the wren.” He had written: “I do not press my finger across my mouth, / I keep as delicate around the bowels as around the head and heart.” These principled inclusions were put severely to the test in the wartime hospital wards, where the smells of diarrhea and gangrenous limbs, the sight of the surgical buckets and fouled bed linens, the sounds of human beings in pain and delirium, would prove too much for many a well-meaning visitor. Squeamishness, false delicacy, disgust were moral failings of the first order in Whitman’s universe and, infinitely to his credit, he refused to admit them.

It is not entirely true, of course, that Whitman never pressed his finger across his mouth. When John Addington Symonds, a deep admirer of the Calamus poems, wrote a carefully worded letter inquiring further into Whitman’s thoughts about “the love of man for man,” Whitman wrote back in high dudgeon about these “morbid inferences—wh’ are disavow’d by me & seem damnable.” He was “as hostile to sexual inversion,” wrote a disappointed Symonds, “as any law-abiding humdrum Anglo-Saxon could desire.” If Whitman’s intimate ministrations in the hospital wards seem less than utterly disinterested to us now, if the rounds of mercy, with their interwoven strands of frankness and occlusion, seem more complexly motivated than hagiography has allowed, these tensions and embargos are inseparable from their urgency. And are kin—though never a simple key—to the urgency of the poems.

The strategic cordonings-off of New Criticism offered a crucial corrective to the sentimental conflations of earlier biographical criticism; the strategic disavowals of Language Poetry, or rather, of its manifestos, offered a timely antidote to the inertias of latter day confessionalism. But neither affords a fully sufficient model for reading. The wish to construe a self “behind” the poem is one of the persistent engines to reading, as “story” is one of the most persistent units of human comprehension. The gestures of self and the lineaments of story: for resilience and momentum and, yes, for subversive possibility, one would be hard pressed to find poetic instruments with richer aptitude. The longing for familiar kinds of meaning, in other words, is unkillable. It is also, crucially, ripe for transformation. So the built self, the simultaneous invitation to and refusal of biographical reading, has the power to lure both reader and writer into genuine discovery. We discard it at our peril. We trust it at our peril.

As an ordinary rule of thumb, one cannot hold a writer responsible for the excesses of his followers and champions. But Whitman was also an eager orchestrator of his own mythology. This goes beyond the notorious strategies for self-promotion: the writing of anonymous auto-reviews, the flat-out lies about print runs and sales figures, the conversion of a private letter from Emerson into the gold-leaf letters of blazon on the cover of Leaves of Grass. It includes as well Whitman’s boasts about the “magnetism” he spread like balm in the hospital wards, the stoking of adulation, the basking in euphemistically unified accounts of his life and opinions. In this one respect we must do better for Whitman than Whitman has done for himself. It was when he brazenly embraced his own disharmonies—”Do I contradict myself? / Very well then … . I contradict myself”—that Whitman offered the truest key to the originality of his contribution. He construed his voice as a public voice, a voice that was capacious enough to “contain multitudes.” The very exorbitance of the poetic instrument is the key to its cunning. And as Strand’s faceless Monument reminds us, that instrument depends, for its cunning and its plausibility alike, as much upon what it omits as upon what it includes.

What it omits is what we are enjoined to provide. “I might not tell everybody but I will tell you,” he wrote, in a poem addressed to every you who would listen. “All I mark as my own you shall offset it with your own / Else it were time lost listening to me.” These are extraordinary rhetorical postulates, entirely aware of their own paradoxical nature. Whitman contrived to speak with unprecedented intimacy in unprecedentedly public terms: for sheer communal reach, the classical epics were as nothing to the Leaves of Grass. His performance of public confidence was nowhere more outrageous than in its insistence on private confiding. And the insistence is a two-way proposition. That reading should be an act of self-discovery in the strong sense, which is to say, self-making (very far from the sentimental exercise we think of as self-discovery today) is a venerable rhetorical proposition. What was new in Whitman were the lengths to which he was willing to go in daring his reader into reciprocity. Invoking the lineaments of selfhood—my body, my appetites, my paths across the pavements and the countryside—Whitman is partly conceding to a common mode of making sense and partly seeking to explode it forever. We mistake the proposition altogether if we filter out the dissonant parts or construe the categories as naive. The self Walt Whitman demands we imagine by means of the poem is the self we would be were we whole.