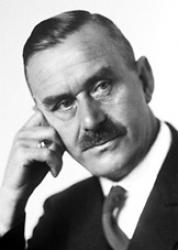

Before Hitler’s invasion of Poland in 1939—and the global rifts that ensued—philosopher, social critic, and Nobel Prize-winning novelist Thomas Mann was watching and, in a way, waiting. According to a New York Times article written in May 1940, Mann was “aware of the implications of the Nazi revolution from the beginning. He prophesied the calamity that would follow, [when] the dove of peace in our time had come to roost on a black umbrella.” In his provocative 1940 pamphlet This War, Mann circumvented Joseph Goebbels’s propaganda machine to question Nazi power and underscore the regime’s crimes against humanity and its power-hungry persecution of European peoples. In his groundbreaking 1941 contribution to VQR, Mann again derided Nazism’s totalitarian politics in an effort to uphold what he described as the “true totality … of mankind.”

But this was not Mann’s first publication in VQR. He had published a brief appreciation of John Galsworthy in English translation in the Winter 1930 issue—when Mann was still living in Germany and just months after he had been awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. When Hitler came to power three years later, Mann and his wife were vacationing in Switzerland, and they elected to stay after Mann’s brother Heinrich’s books were publicly burned in Berlin. In 1936, Mann’s German citizenship was revoked, and he emigrated to the United States, where his democratic beliefs and open opposition to Hitler’s heavy-handed totalitarianism made him a leading writer of German “Exilliteratur” (exile literature).

Despite his international prominence, the publication of Mann’s “Denken und Leben” (“Thinking and Living”) in VQR’s summer 1941 issue was a milestone, not only for VQR, but for an American print culture that was, at the time, intensely wary of European influences. In the months leading up to the attack on Pearl Harbor, the American public was increasingly isolationist, not wanting to bring the war—with its accompanying nationalistic and cultural antagonisms—to our shores. The US economy was reeling from the Great Depression, and the possibility of a military crisis struck many Americans as potentially catastrophic.

Nevertheless, VQR began to print more and more articles about international events and issues, reframing its scope from a “national journal” to a wider geopolitical sphere. This development in VQR mirrored, and in many ways responded to, President Roosevelt’s own increasingly internationalist perspective, as his administration began to provide financial and military support to the Allied cause. Already a pro-New Deal, pro-FDR publication, VQR solidified its internationalist-leaning position with the appearance of Thomas Mann’s article—not only because it directly confronted Nazism in Germany but also because it was printed in German without an English translation.

The symbolism was no accident. On March 8, 1941, VQR’s managing editor Archibald Shepperson (who later assumed the editorship in 1942) had written to Mann, requesting “an article in German”:

This will be the first, and perhaps the only time this magazine will ever have published anything in a foreign language without an accompanying translation. It is a gesture which we wish very much to make—with your assistance. I do not think it is necessary to elaborate on our reasons for wishing to do so.

Mann responded immediately—and enthusiastically:

Your kind letter of March 8th was indeed a happy surprise to me. The idea of publishing at this moment in your review a contribution in German has something moving for me. And I certainly accept your invitation with particular pleasure.

Shepperson hoped to use Mann’s literary renown and antifascist reputation to break the growing association of German culture with Nazism. In a detailed introduction in the “Green Room” of the issue, Shepperson described the essay as:

a series of reflections on the disconnection between philosophy and life in modern Germany and on the dire results which will come to any country in which such disconnection is permitted to continue. These “reflections upon the duties of Philosophy to the realities of life” were prompted by the motto, “Philosophy, the Guide to Life,” engraved upon a small golden key, presented to Dr. Mann in March of this year by the Phi Beta Kappa chapter at the University of California. The novel suggestion that Nietzsche, if he were alive, would in all likelihood be an exile in this country and perhaps the recipient of a Phi Beta Kappa key himself becomes less surprising when we are reminded that on the death of Emperor Frederick III, the liberal Anglophile, Nietzsche wrote that the hope of German freedom went with him to the grave.

To emphasize the importance of the German text, Shepperson refused even to publish publicity clips of “Denken und Leben” in English, but an English translation was undertaken by D. O. Robbins and published in The American Scholar as “Thought and Life” in late 1941. For the ease of our readers, the typescript pages of Robbins’s translation—taken from the VQR archives—are presented here.

At the beginning of his essay, Mann blames the wavering aspect of the German spirit, and not the influence of Nazi politics, for “the weakness of democracy in Germany.” Historically, Germany had been a stronghold of philosophy and social thought—think for example of the revolutionary legacies of Engels, Marx, Nietzsche, and Weber—and so it was distressing for Mann to imagine that “there would be no more philosophy,” and certainly ”no democracy … no religion and no morality,” if Hitler was successful in his ultimate bid for world dominance.

In response to this spiritual faltering, Mann offered the need for “a certain simplification and rejuvenation” of morality—such as a clear dividing line between good and evil—in order to counter the disturbingly straightforward aspect of what he termed Nazi “deviltry.” According to Mann, the “moral catastrophe and devastation” that would ensue if Nazism prevailed in World War II would be too terrible to imagine; it would mean “the ultimate triumph of evil in the world, the triumph of deceit and force.” In Mann’s opinion, the German spirit could be galvanized into some semblance of unified expression by rallying around a clear and enlivened sense of moral consciousness. And more generally, the world—if willing to band together in a “true totality”—might yet defeat Nazism and preserve democratic forms of thought and practice for the future.

Manuscript

- “Thought and Life,” a translation of “Denken Und Leben”

Mann’s work published in VQR:

- ”An Impression of John Galsworthy,” Winter 1930 issue

- ”Denken Und Leben,” Summer 1941 issue

A selection of work about Mann published in VQR:

- ”Poetic Reason in Thomas Mann,” by Vernon Venable, Winter 1938 issue

- ”The Manns: Mirrors of History,” by Jeffrey Meyers, Autumn 1979 issue

- ”Thomas Mann As Diarist,” by Jay Parini, Summer 1984 issue

- ”Why Thomas Mann Wrote,” by Cecil C. H. Cullander, Winter 1999 issue

- ”The Brothers Mann,” by Cecil C. H. Cullander, Spring 1999 issue