Peshawar and Karachi, Pakistan, January 2, 2008: Mohammad Alam, an elderly, wrinkled man wrapped in a tattered blanket, guarded his street corner in Peshawar last Friday, while angry mobs burned a motorcycle, ransacked the chamber of commerce building, and threw stones at police just a few feet away. Even as the sound of gunfire clattered nearby, Alam didn’t dare leave the kiosk where he sells neswar, a type of chewing tobacco widely used by Pashtuns; the thirty bags stacked neatly on the box beside him—and worth a total of about $1.50—constituted his entire inventory and livelihood. But when police began chucking shells of tear gas at the protesters, a cloud of gas engulfed Alam’s business, and left him no choice but to run. “I was vomiting the whole time,” he said. I talked with Alam only about half an hour after police fired the tear gas, and chemicals still wafted in the air, stinging my eyes and nostrils. I asked Alam how many bags of neswar he had sold that day, but he brushed aside the question. “I am not concerned with money today,” he said. “I only worry about keeping my corner.”

Anarchy and lawlessness have prevailed in Pakistan since Benazir Bhutto’s assassination in Rawalpindi on December 27. In the hours and days after, rioters ran wild through city streets, torching buildings and looting banks. Thousands of stores were ransacked, despite the best efforts of those owners who tried to guard them. And people whose businesses run on open street corners not shops they could shutter, people like Alam, were forced to flee. He left his bags behind at the mouth of Peshawar’s main bazaar, but in the confusion no one robbed his stash. He was fortunate; these days were opportunists’ days, Alam told me. “You could lose everything you own in a just an hour or two.”

The economic impact of the riots and violence has been tremendous already—not to mention the longer-term effects it will have on foreign investors’ confidence. In Karachi alone, approximately $130 million in revenue is lost every day, not including damages to property. As of Tuesday, most stores there remained closed, with both merchants and shoppers taking cover from the sounds of sporadic gunfire. The violence couldn’t come at a worse time for Pakistanis. The prices of basic commodities like wheat and sugar are higher than ever, and remain one of the main reasons for President Pervez Musharraf’s plummeting popularity—and his persistent desire to forestall elections. When I asked Mohammad Shah in a village outside of Peshawar whether he planned to vote in the elections (then slated for January 8), he answered, “Why are you asking me about elections when I have no food? Elections are still ten days away, I have no food now. I don’t know if I will be alive in ten minutes. If anyone brings me a sack of flour, I will vote for them.”

It’s easy to understand such as a philosophy here. Even as the carcass of the burnt motorcycle still smoldered in front of Mohammad Alam, two young boys—no more than twelve years old, their faces, hands and clothes filthy—picked through the debris. They collected sooty pieces of scrap metal that they said they could resell for about twenty rupees a kilogram. When I asked one of them how much he’d gathered, he stopped rummaging for a second and held out his plastic sack with a straight right arm. “Two, maybe three kilos,” he said. He looked pleased with his find.

But who, besides poor kids collecting scrap, stands to gain from Bhutto’s death? Musharraf’s government is scrambling to come up with a coherent explanation and the retired general’s hold on power seems more tenuous than ever. Members of his faction of the Pakistan Muslim League have totally stopped campaigning out of fear. Many pro-Musharraf candidates have gone into hiding. In Bhutto’s home province of Sindh, mobs ransacked and burnt eleven offices of the Election Commission, torching all the voter registration information stored inside. The ongoing threat of violence—or another assassination—jeopardizes the possibility of holding free and fair elections anytime soon. And yet, Bhutto’s Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) have threatened to protest the postponement of elections, raising the possibility of more violence. Fortunately, Washington seems to recognize the gravity of the situation, and has withdrawn its insistence that elections be held on time. On Monday, a State Department spokesman hinted that a slight delay would be acceptable, adding that, “The key here is that there be a date certain for elections in Pakistan.”

At the moment, the date has been moved back to February 18. Regardless of the timeline, the transition to a new government is likely to be violent. That’s nothing new; Pakistan’s history is a bloody one, dating back to the country’s inception in August 1947, when millions died during the Partition of India. Four years later, a gunman shot and killed Liaquat Ali Khan, the country’s first prime minister, in the same park where Bhutto was killed last week. Over the past sixty years, every transition between governments has been mired in blood and conspiracy. The army has seized power four times. The military regime of General Zia ul-Haq overthrew Benazir Bhutto’s father, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, in 1977, and hanged him two years later. Zia then died in a mysterious plane crash in 1988 that also killed the American ambassador, five of Zia’s top generals, and more than twenty others. In the ensuing election, Bhutto’s PPP won control of the National Assembly and Benazir was sworn in as Prime Minister. But Musharraf too, it should be remembered, took power by ousting the sitting prime minister, Nawaz Sharif, in a military coup in 1999. (This past parliament, in fact, marked the only time an elected government in Pakistan had fulfilled its term in office.) That Benazir, with her outstanding record of corruption, and her father, whose authoritarianism knew no limits, both died early is not so much the result of some supernatural curse on the Bhutto family, as some American media outlets have suggested, as a reflection of the realities of Pakistani politics.

But the PPP’s announcement on Sunday that its new chairman-for-life would be Bhutto’s nineteen-year-old son Bilawal offers arguably the most vivid illustration of Pakistani politics yet. Smart and good-looking like his grandfather Zulfiqar, Bilawal might someday make a good politician—if he ever finds something important to say. But the message is often irrelevant. Lineage and caste are much more important in Pakistan, which explains why Bilawal Zardari (named after Benazir’s husband, Asif Ali Zardari) changed his name to Bilawal Zardari Bhutto just hours before accepting the chairmanship. At the press conference where the PPP introduced Bilawal, a student at Oxford, as the new figurehead of Pakistan’s largest party, supporters chanted: “Yesterday, Bhutto was alive! Today, Bhutto is alive!”

Maula Baksh, a resident of Karachi and longtime supporter of the PPP, offered the best explanation of “Bhuttoism” I’ve heard yet. Last year, as Benazir Bhutto was planning to return from exile and engaged in backroom discussions with Musharraf, I asked Baksh how much Benazir’s dealings with Musharraf would damage her popularity, especially in the slums of Karachi and throughout Sindh. Baksh smiled and told me that her support had more to do with the mythic, untainted legacy of her father, than anything she had actually done. “Take a pillar, put it in a public square, and write Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto’s name on it,” Baksh said. “People will vote for the pillar.” In Peshawar last week, I marveled at how Benazir’s face covered billboards throughout the conservative city, while local women, the few who ventured out, shuffled along the pavement in head-to-toe burqas. In many ways, cultural and religious mores don’t apply to the Bhuttos.

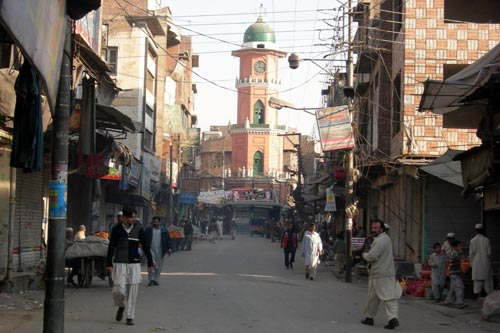

Most people I have spoken to over the past week expect the PPP to ride a wave of sympathy through the elections and into the national assembly. The question remains, however, can the PPP shake common people from their apathy and get them to the polls? I spent most of December traveling throughout the country gauging public sentiments ahead of the elections, and found most people on the street unprepared to cast their ballot. “I can’t worry about politics. I can only think about my business,” said Faisal, a stocky man who runs a currency exchange shop in the Peshawar bazaar. He described politics as being like polo or golf: “The rich are the only ones who can afford to play.” I met Faisal inside the winding streets of the bazaar the day after Bhutto’s death. Besides the butcher and milk shops, all the other businesses remained boarded up. You could hear the sound of footsteps in the alleys of the usually hectic market. Children played cricket in the empty streets. Faisal, when asked how he thought Bhutto’s death would impact the political situation in the country, told me, “We will just give our country to the United States. Our leaders are not up to the task.”

Yet even as Democratic hopefuls for America’s presidential race jockey to look strong on Pakistan—America’s leading foreign policy challenge in the coming years—the White House continues to place its confidence in Musharraf. To some extent, even top analysts in Washington hold onto some confidence in Musharraf’s ability to lead this country. Wendy Chamberlin and Marvin Weinbaum, writing in a column that appeared in the Washington Post last weekend, said that Musharraf would “instantly win” national approval if he restored the several dozen judges he recently deposed, set up a new, federal election commission, and lifted all restrictions on the media. And in fact, they are right. All these goodwill gestures would salvage some amount of Musharraf’s credibility. But have Chamberlin and Weinbaum been watching Musharraf for the past year? Have they seen something I haven’t? Despite Musharraf’s best intentions, he can no longer play any positive role as head of the state. His mere presence divides the country. “Now the time has come for Musharraf to tell us how many heads he wants,” said Wajid, a man in his late sixties whose eyes welled with tears on the morning following Bhutto’s assassination. “We, the common folk, are ready to go to Islamabad. We are ready to die. Just please, please tell Musharraf to stop killing our talented people!”