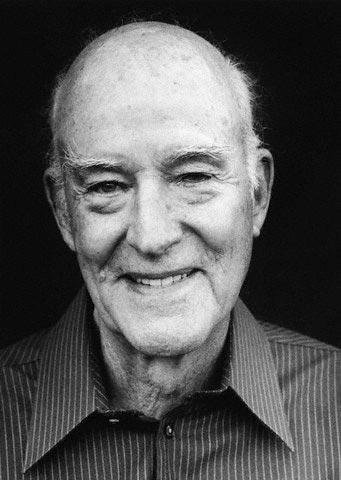

Hard to believe how I myself am now older, older by far, than Robert Irwin was when we first began having our conversations, coming on thirty years ago. Fresh out of college, a classic, overstuffed instance of surplus education, I had been working at the UCLA Oral History Program, editing other people’s oral histories of various local luminaries in the context of an NEH-sponsored series, “L.A. Art Scene: A Group Portrait,” when, working my way through someone else’s interview with this artist I had up to that point barely even heard of (which, granted, said more about me at the time than about him), increasingly engrossed, I decided to hazard writing the guy a note, which read, in its entirety, “Have you ever read Merleau-Ponty’s The Primacy of Perception?” Whereupon there he came knocking at our door the very next morning. I’ve always felt that had I sent Irwin that note even six months earlier, he’d likely have dismissed it as so much hyperintellectualizing claptrap. But it just happened that he was at a point where he was going to be giving himself over to precisely that sort of reading for a while.

And so we ended up having lunch together for the next three years; which is to say that he pretty much planted himself under a tree up by the North Campus library, doggedly poring through the great classics of the philosophic tradition for hours and hours at a time, such that I always knew where to find him during my lunch breaks. Two or three times a week I’d head over and there he’d be, drilling away, dark baseball cap scrunched over his broad forehead, colored pens clutched in his fist, the book in question splayed prone; and we’d take to conversing, me telling him stories about philosophy and history and suchlike, and him telling me stories about art and cars and horses, stories which in turn would come to form the basis for Seeing is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees, the book, my first, that I was subsequently able to fashion and bring out five years later, at a moment, it occurs to me, when he was still younger than I am now.

Twenty-five years on. And yet, once again, it starts, as it almost always seems to, with his pulling in to pick me up in his new car (this time, improbably, a snazzy silver BMW coupe), the car radio wafting forth the usual medley of forties swing, and our heading out into the balmy breezy Southern California light, just getting going with our catching up when he almost immediately has to interrupt things to pull in to his current neighborhood Cola boîte (this time an otherwise nondescript gas station/car wash/mini-mart/sushi bar), whereupon, replenished (“Where were we?”), he proceeds to squire me over to his latest digs.

Which this time turned out, even more improbably than usual, to be in the heart of a gleaming new medium-upscale tract development, the Gables, embedded in the middle of a yet wider Spielbergian subdivision, Torrey Hills, part of the relentless suburban sprawl north of San Diego, one two-story Cape Cod pressed against the next, narrow front lawns, ostentatious porticoes, faux-Corinthian columns, gently fanning sprinklers, the sidewalks lined with tricycles and miscellaneous other kiddie roadsters abandoned in midspree, basketball hoops hanging from double-garage entries, every single home girdled in the colored lights of the just concluded Christmas season. “Yeah,” Irwin admits, “I broke out laughing the first time I saw it, too. But our daughter Anna Grace was growing up and we were fast outgrowing that apartment overlooking the harbor, and I asked my wife Adele what she’d want in our next neighborhood if we were to move, and the first thing she said was, ‘Kids on the block,’ and, as you can see, there are plenty of kids. And as it happens, our own house . . . this one . . . right here,” he gracefully swung the Beamer into the driveway and pulled to a stop, killing the swing, “is actually quite nice.”

Which indeed it was: tall ceilings, high windows, clean through lines to a cozy backyard, beyond which spread an empty open expanse, and off in the middle distance, a freshly graded, beige-bare, suburban hillside, rutted in dry rivulets (like a Georgia O’Keeffe mesa); while back inside, a little three-sided patio graced the middle of the compound (a two-story lightwell, as it were), along one flank of which he’d secreted his office—the same office, cleanly transplanted: angled drafting table, high director’s chair, swivel lamp, fanned-out color swaths, reference texts, architect’s plans curled into long tube canisters. Upstairs the muffled footfalls of his now thirteen-year-old daughter. Outside the brimming chatter of the rampaging neighborhood kinderposse.

“Yeah,” he agreed, catching my eye and preempting my drift. “But it’s like that old friend of ours, the Philosopher and his Walk.” (Taking us both back to the stories we used to exchange under the tree at the North Campus library, this one about Immanuel Kant in Königsberg.) “Same time of the day, same route, every day the same walk, people said you could set your watch by the guy. It was like, ‘Well, it must be three o’clock,’ you know? The point being—one of the things I got from that was that if you were going to put things up for grabs like those people did, and I mean, everything, man, you could just explode. And some of them probably did at one point or another. Just spun out: Nietzsche. Most people think, ‘Oh, I want to be far out. And to get there, I’m going to live this truly chaotic life.’ But it doesn’t work that way. To really do what they did—to let yourself drift that far out—there has to be a sense of underlying order that keeps the whole thing grounded.” He laughed and rolled his eyes, gesturing behind himself at the kinderchatter.

By which measure Robert Irwin must be about as far out as he has ever been. He’s certainly chugging along, at any rate, busier than ever at a brisk age seventy-eight, with more projects than ever seemingly on the cusp, tantalizingly on the verge.

Several of them right there in San Diego. The house (in another repetition of his earlier life) lies roughly halfway between the legendary Del Mar horse-racing track and the San Diego Museum of Contemporary Art, nestled on a bluff overlooking the churning Pacific off La Jolla. The museum, as it happens, being the site of one of Irwin’s finest semipermanent interventions of the past decade.

“You like that one?” he says, when I bring it up. I tell him it’s a really great piece. “Yeah,” he concurs, “it’s one of my favorites as well. And one of the things I really like about it is how it’s almost effortless.”

Or, anyway, appears such. I ask him how it came about.

“Well,” he explains, “the thing about that whole museum out there on the bluff is that it began as a house, somebody’s home, somebody’s really nice La Jolla home, and for all the work they’ve done on it since, it still retains a bit of that flavor, with that one room in particular, with its three walls of windows jutting out into the view . . . And I mean, there are views and there are views, but that is one spectacular view, with the rocks and the waves, the curve of the beach, the palms and the pines, it’s the La Jolla view. And intuitively, they’ve never closed that room up, even though they really could use the wall space, wall space being something this home was otherwise a little short on. They’ve left it. And over the years I’ve always marveled at that a little bit, you know—that they did leave it. Which was a very aesthetic kind of decision to make. I would go to see a show there, and they would never quite know what to do with this room, they might stick a piece of sculpture or something in there which would invariably get swallowed up by the view. But people would drift in there, people who might not like the show or didn’t like modern art, and they’d say, ‘Ah, now this is really,’ you know, ‘this is what I call art.’ And I always thought that was a great statement, and an opportunity. So when the museum’s director, Hugh Davies, who’s been a longtime friend and supporter of my work, invited me to do a site-conditioned piece somewhere there in the museum, I chose that room, and tried that idea of getting people to make that shift —you know, one dimension, two dimension, three dimensions, four.”

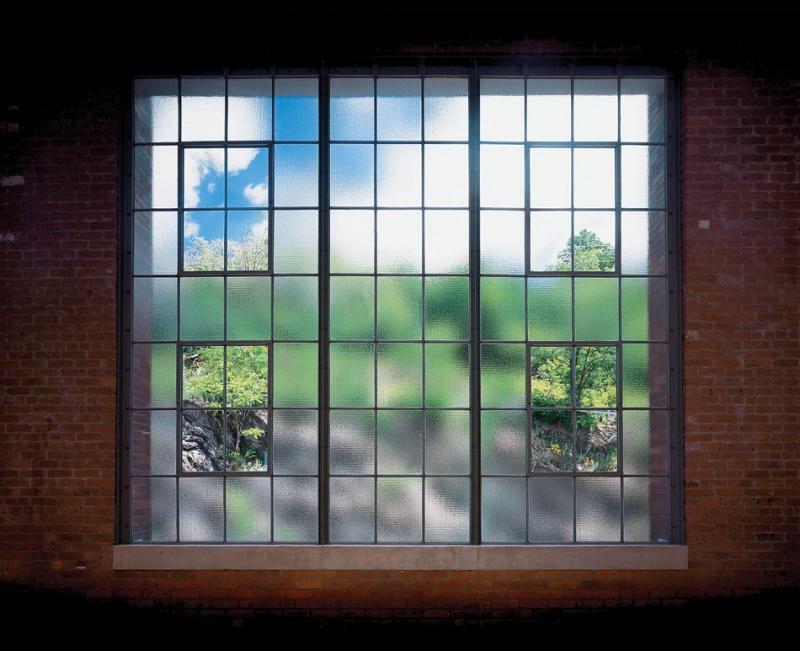

The window glass is fairly dark.

“Actually, yeah, it’s tinted slightly, but very slightly, not so that you would otherwise notice it, except that then I cut a square of empty daylight, as it were, into the middle of the window, through the glass . . .”

And the world outside, the actual world beyond the window, is dazzlingly bright, almost a whole other order of being. The whole thing constituting a marvelous inversion, a literalization of the conventional Renaissance trope of a painting’s being “as if” cut into the wall, like a window . . .

“Precisely. In a way it’s like what I always argued about Pop art, how people who saw its upsurge in the early sixties as a refutation of abstract expressionism or a turning back to figuration were getting it all wrong. Rather, it was a case of taking the lessons of abstract expressionism, that heightened overall focus over the entire picture plane, the further leavening of such hierarchies as figure and ground, and taking that aesthetic back into the world, applying that way of seeing to the most common objects in the world, taking, say, a humble, meaningless Campbell’s Soup can and lavishing that sort of even attention on it, too. And here, it’s like I am saying, you know the kind of attention you have been taught to lavish on a Renaissance landscape within its as-if window frame, try lavishing that sort of attention on the world itself. In fact, get rid of the window! Just experience the world!”

And then, as well, in the corners of the room, where the middle facing window plane joined with the two similarly tinted side-windows . . .

“Yes, because that was the next move. Once I’d carved out that little square of plain air in the middle of the central window, which incidentally turned out to be quite a technical task to accomplish (to do so without shooting hairline fractures into the rest of the window), the whole thing didn’t yet seem quite complete. I kept trying to figure out what to do to complement this window, I tried this and that, and then all of a sudden, tschhhh, I had this idea, to carve out a further square of empty air at each corner, but one that followed the perpendicular meeting of the window planes, half square abutting half square . . .”

Producing a sort of Necker cube illusion.

“Exactly, but also giving the piece a whole further dimensionality. And it was like, wow. Because now you’ve taken the frame and sort of bent it, which just brings that into even more focus, it turns out that before it was slightly out of focus but now, bang, it snaps into focus, becoming completely pictorial while in fact being the opposite of pictorial, which is to say experiential, because on top of everything else now you get the sounds drifting in from outside, and the soft breeze blowing, the whole thing becoming truly four dimensional.”

It becomes both crisper and more diaphanous, somehow at the same time.

“Yeah. Oh yeah. You bring the issue into focus, and people are forced to suddenly deal with the whole concept in one whack.”

Literally by his framing everything that is unframable.

“And it does all of that like, pshhht—as if, you know, by magic.”

That piece in turn reminded me of another one from a bit earlier, actually from the Paris incarnation of the touring MOCA retrospective. There, in the City of Light, the retrospective had come to nest in the Musée de l’Art Moderne, situated in a peculiarly arch-neomodernist 1930s pavilion across the way from the Eiffel Tower, the top floor gallery of which infurled along a slow arcing spiral, softened by somewhat grimy skylights in the ceiling above. As the climax of that version of his traveling retrospective, Irwin had slowly ramped up the floor along that incurling spiral across a succession of almost imperceptibly staggered -inch plywood risers, while, up above, he’d cleaned the grimy skylights, in turn covering them over with a succession of ever deeper theatrical gels—pale yellow across an increasingly insistent series of oranges on through, finally, to a red so intense that experiencing it felt like being in a blast furnace.

“By the time you’d gotten to the far side of spiral,” Irwin recalled, “you were maybe eighteen inches closer to the ceiling than when you began, and the ambient light, hardly noticeable at first, had grown so overpoweringly strong that it was almost teeth-rattling—though, secreted like that into the skylight, as opposed to painted onto the wall, you couldn’t quite figure out where the effect was coming from. Which made it all the more unsettling.”

And then, two steps down, you entered a square white room bathed in the most heavenly, serenity-drenched blue light.

“Yup.”

And how had he done that, what did he do?

“Nothing,” Irwin replies, a smile breaking across his face. “Nothing: that was just the pure, unadulterated light of Paris. Though, granted, light which that earlier procession had optically conditioned your eye to see—blue being the opposite of red—so that in fact it might be more accurate to say that the main thing you were becoming aware of was the workings of your own eye. But no, I didn’t do anything to that room; that was just the light of Paris streaming in through a side window and a little square skylight above, a light which people otherwise tend to get way too overly habituated to.”

Ground Zero again, I remarked, referring back to the rectangle of string pulled taut through which Irwin had intended simply to frame the way tree-shadows dappled an expanse of ground—that constituting his entire contribution to the 1976 Venice Biennale.

“Yeah,” Irwin agreed, “and the funny thing about that is that Hugh Davies, the guy here in San Diego, was involved in that piece as well.”

Really, how so?

“Didn’t I ever tell you the story of how that piece came about? Well, my relationship to Hugh goes way back. His first job as a museum director, I think, was at the University of Massachusetts, where he put together a show, basically a painting show, but he had included one installation person, which was me. So I went there and I did a scrim on a staircase in the entrance to the place. Which came out—not bad. Pretty good piece. Very simple, but it had a nice impact.

“Anyway, for some reason, that particular year, 1976, they decided not to generate a special new show for the American entry at that year’s Venice Biennale, you know, select a curator and have him mount a whole fresh exhibit. Rather, they decided to go on the cheap and just send this already canned show. So here’s this young guy, Hugh Davies, it’s his show, and he’s taking it to the Biennale, which is a pretty big deal. There’s another guy whose name I don’t remember but who’s an old heavyweight who’s in Washington DC, basically pulling the purse strings, okay? So Hugh, with great enthusiasm, calls me to say, ‘We’re going to do this, you’re going to come.’ You know, terrific, the whole thing. And he offers me the world—or anyway a chance at the international big time.

“But when we got there—I don’t know if you’ve ever seen the US pavilion—it’s a small little antiquated building. A little patio in the middle and two wings and—well, small. So basically the show pretty much fills up the whole space, you know? But he’d asked me to—and I’d come, and I’d come up with a plan for the whole thing, in a way. He’s excited about it, I’m excited about it. I’m in the Venice Biennale. Also, I’d never been there, and it’s a complex world. Very competitive and the whole thing.

“So anyway, I come up with a piece and he passes it on to the guy in Washington DC, and the guy in Washington DC, says, ‘No, we can’t do that. It would overshadow everything else in the show.’ So Hugh comes back to me and he says, ‘Well you know this guy . . . Could you like look at it again?’ So I do look at it again but I realize that, man, there’s almost no place. So I work up this proposal for a whole thing up in the rafters of the place, up in the ceiling. Hugh likes it, he sends it back to this guy in Washington, D.C„ and the guy said, ‘No, it’s still too much. It’s overwhelming everything. I don’t think there’s really any room for it in there.’ So Hugh comes back and says, ‘Well, the guy says, you know, there’s no room. But could you look outdoors?’ So I say, ‘Yeah, sure. I’ll look outdoors.’

“So I’m outside in the patio area, and it’s complete chaos out there, you know what I mean? I’m out there, kind of looking around trying to figure out what I could possibly do, and I’m sitting on a bench, watching these leaves fall between these four trees. Kind of a nice little bosk of just four trees. And this guy comes over, Israeli artist named Danny Caravan. Sort of well known with a pretty good reputation. He comes over and we start talking and he asks, ‘What are you doing?’ and I kind of tell him what I’m doing, and he says, ‘Oh wow.’ And he’s got his critic with him. The Europeans all do that: They tend to bring their own critic with them. And his critic says, ‘Oh wow.’ And it turns out he’d been there for six months preparing his thing. And he had like a budget of a million and a half or three quarters, you know what I mean—he had a real budget. So now, I’m like, ‘Oh wow’—I’m laughing, sort of sitting there and listening.

“So they leave and I’m sitting there, and Hugh comes out. He comes out, all sheepish, and he says, ‘God, I really hate to tell you this, but the guy in Washington says we have run out of money.’ So I’m sitting out there, I’ve been kicked outdoors, we’ve got no money, and the whole thing has taken on a comic opera sort of quality. So I’m sitting there watching these leaves fall down and it’s—actually it’s a really beautiful sort of composition. And I get this idea. So I go to the hardware store and I buy these four great big nails, you know, and a piece of string. And I put the four nails in the ground and I put the string around the nails. And I tell Hugh, ‘There’s your piece.’

- “String Drawing—Filtered Light,” Irwin’s four nails and string in the courtyard of the US Pavilion, Venice Biennale, 1976 (Hugh M. Davies).

“And, you know how sometimes I’ll do a piece and not hear a word about it for the longest time. Like when I did that piece at the Museum of Modern Art in 1970. Well, this time I really didn’t hear anything, never heard a word about it. It was like it had never happened—and it probably almost didn’t exist with all the people walking among the pavilions and the cacophony of sound that goes on there: this very subtle thing.”

Irwin shook his head, smiling at the memory of it. “And then—this was about, I don’t know, let’s say eight years later or something, I was asked to come to St. Louis, where this lady, Emily Pulitzer, nice lady, good collector, and a real activist in that community, she was convening a juried competition for a big project, me and three other artists. So I go in and I do my presentation and the whole thing and I come out, it’s the next guy’s turn to go in but we’re out there exchanging pleasantries for a minute, and I can hear the jurors talking back in the other room and this one guy says, ‘I don’t care what the rest of you think. I vote against the son of a bitch.’ That’s the expression he uses. ‘I vote against the son of a bitch: what he’ll do is he’ll just come in and put a piece of string on the ground, take all the money and run.’

By this point Irwin is guffawing. “I mean, that’s great story isn’t it? Not only don’t I even get paid for the one piece but it ends up costing me a whole ’nother one.”

And then there was the question of credit.

Shortly after the 1997 completion of the Central Gardens at the Getty in Los Angeles, his most mammoth and ambitious project to date, and in the context of his subsequent ongoing triumph with a ravishingly luminescent scrim-hive at the Dia:Chelsea’s space, Irwin began talking with Dia’s director, Michael Govan, about the challenging crossroads that institution seemed to be coming to.

“Michael recognized that they were facing a problem,” Irwin responded when I asked him how that next phase in his activity had gotten started, “in fact the same one that MOMA had years and years earlier. MOMA, too, started out in a sense as an interactive institution, as a sort of forum for dialogue, which is the first role of a really good museum, okay? And did so in their case at a particularly good moment in time, so it turned out to be one hell of a trip. But in the process, the Modern - which was never supposed to have a collection, I’m told – accumulated all this incredible material. They were tuned in to everything that was going on and thus got some of the very best examples of what was. So suddenly they had this perfect museum dilemma, which is, they have all this material, what are they going to do with it? They can’t just leave it in the basement. They can’t just bury it. They’ve got to deal with it. They’ve got to take responsibility for it. And the Modern made a good decision, maybe even the right decision, which was to become what we now know as the Modern, which is essentially a collection. No longer an interactive institution. No longer alive in that initial sense. It’s a sort of natural evolution of museums in a way, in that when they really are a great museum in the initial sense, they run the risk of ending up with a great collection and becoming a great museum in the second sense, and then beyond that, in a third sense, becoming primarily devoted, shall we say, to education, to teaching and helping people to understand their own history.

“Now, Dia had really been an active museum in the first sense, devoted to cutting-edge contemporary inquiry and practice, and was continuing to try to be so, but they came to realize that in so doing, they’d built up this huge basement collection of great work from the next generation or two down from MOMA’s, the so-called minimalist heirs to abstract expressionism. People like Heiser, de Maria, Serra, Agnes Martin, Warhol, Beuys, Smithson, Flavin, Judd, and so forth. Which is a big responsibility. So my understanding of it is that, by contrast with the Modern, Michael at Dia decided he’d try to farm out the collection side of things off-site, to some yet-to-be-determined campus outside the city, to do that as well and as responsibly as possible, but in part so that they could get back to work on what they really do.”

The story goes that Govan, an avid amateur flyer, was day-tripping up the Hudson River valley one afternoon, pondering this dilemma, when down below he spotted the abandoned factory site, outside Beacon, about a hundred miles north of Chelsea, which would come to solve his museum’s dilemma: a dilapidated onetime Nabisco box-printing plant in an increasingly derelict and abandoned part of the state (hence one subject to potential state financing support). And several chutes and ladders, hoops and sluices later, Dia had in fact managed to come into possession of the wretched pile, though in fact a pile not as wretched as all that.

Govan started taking Irwin up to walk through the premises. “It had a beautiful site,” Irwin recalls, “on a hillslope overlooking the river; a convenient location, just a few hundred yards south of the local Metro North train depot; and its interior featured clean Bauhaus lines, harking back to its original 1920s industrial construction, along with some wonderful light, or you could see that it would be, once the banks of north-facing skylights were cleaned.” They got to talking, and presently Irwin came on as the principal consulting designer for the entire project, even transplanting his family for over a year to wintry and decidedly un-Californian upstate New York.

“Basically what they asked me to do is operate as a kind of master planner,” Irwin recalls. “Which was a terrific opportunity for me, because it allowed me to do what I’d already done at the Getty, only to do the architecture as well—in this entirely different venue with a whole new set of issues but still in the context of that same compounding site-conditioned approach. Such that, for example, in this instance, the building, for all its simple clarity of design, had been a cookie-cutter building. That is, they’d actually built six identical such structures in different parts of the country. And the key driving element for each of them had been those north-facing skylights, which provided a great way of saving money on electrical lighting. So when they dropped the factory down on each site, they always had to face the skylights north. But when they faced the skylights north on this particular site, it ended up making the orientation of the building totally bass-ackwards. That is, the entrance—instead of facing west to the river, which would have been the reasonable choice, or even toward the parking lot to the north, which would have facilitated the natural comings and goings—was on the east side, which faced right into the hill. So all the fenestration on the building, the decoration, the quality materials and brick and all that, were all on the east side facing into this hill. And the other sides in turn had the lowest grade brick, almost no fenestrating, no decoration—none of the niceties, right?

“So the first thing I had to do is literally spin the building around, ninety degrees counterclockwise, so that it would actually work on the site—that turned out to be the biggest single move, and nobody had thought about that. But that in turn meant that you would be having to approach the site through the parking lot, which in itself was one of its ugliest elements, the bane of any architect’s life: all those cars. On top of which, Michael and the Dia had this idea about how one ought to enter an art space, not through a big lobby, and not through a book store or a café—like all the other museums have become in a way—but directly, unmediated, right into the art experience.

“Thus, from the outset we had this challenge of how to structure the moment of arrival. So our solution: let’s say you arrive at the train station and you walk the few hundred yards south toward the museum, you climb up this hill from the top of which you now look out onto this driveway sloping down into the parking lot below with the building off in the distance, and that is your first exposure. I decided to make the parking lot into an orchard. In other words, I sacrificed some parking spaces and that—but created a situation in which there were enough trees hiding the cars such that you looked down on this really quite lovely and inviting sort of place to go. And then you walked down the driveway and you were at this next level”—he was now penciling in quick sketches across his drafting board—“and that became a sort of second moment of entry, because suddenly you were on this axis where you were going right up the middle to the entrance of the building, which is pretty strong. Pretty powerful.

“The trees, by the way, were hawthorns—they’re like a fruit tree, not unlike a cherry tree or something, nice structure, nice scale. Scale, by the way, being very, very important. The trees, and they are getting close to that, will become exactly the height of the building, so that they’ll become a mass in front of the building, and hence an architectural element. So now we’re not talking garden at all. We’re talking architecture. And the other great thing about these trees is that the berries come out in the winter, which is otherwise the worst, the most depressing time of the year there. The tree is nice in the spring, it’s nice in the summer. It’s brilliant in the winter. Right the opposite of how it would normally be. You get just this haze of berries, bright orange, like one of my paintings in a way. Beautiful. It’s one of the prettiest . . .

“So now you continue moving forward toward the entry, and the trouble is that the building, especially on that side, was flat-out cumbersome. It was squat and ugly, and we didn’t have any money. It wasn’t in the plan to change the facade of the building. So I changed the ground plane of the approach, using the cheapest and simplest kind of material, like the rebar at the Getty, these interlocking cement blocks with tufts of grass shooting up between them, the plinthlike elegance of the ground drawing your attention a little away from the squat inelegance of the façade. And then, too, we pitched the administration building and café/bookstore over to the left side, a bosk of trees and a view platform looking out over the river to the right, these two lateral masses, so that the whole thing felt like you were already in an interior sort of space, as you now approached the entry itself. And the thing there was—this goes back to the ass-backwards placement of the original building. The little side structure off to the side of the building, smack in the middle of the approach, had originally been closed off: it had housed these restrooms, and in the early days we’d always had to enter through a little door off to that structure’s side and then go back through this low area before we’d get to that great moment of arrival with the space and the light and the scale all spreading out before you, the whole interior expanse, just like, wow, you know? Major, major.

“So of course I pulled out those restrooms and replaced them with an elegant little sort of entryway, a little place to take the tickets, hang a coat or whatever, whose real function was to bring you down in scale, so that you went from outdoors, great light, great sense of outdoors, through this semi-dark space, only a little indirect light coming through skylights, a couple of positioned windows. And then, a few more step and the whole wide interior space opened before you, through a set of double doors, left and right, because in fact, the factory consisted of two of these cookie-cutter structures pressed one against the other, cheek by jowl, adjoining carbon-copy structures with the central spine—you’re entering right on the axis—being the wall which now ran clean to the back of the building. Which fortuitously is facing south, so that the windows down at the far end are getting the strongest hit of light, right? So visually you’re looking three hundred feet down this whole thing, your eyes being pulled all the way down, so that you get the whole scale, the whole plan in one hit. Whether you cognate it or not. That and the sense of doubling and the choices it demanded of the visitor. They ended up putting Walter de Maria pieces down the length of both galleries, to either side of the central spine. If I’d had my way I’d have put someone else, maybe Warhol, down one of these sides, so as to emphasize the recurrent theme of free choice from the very outset. Still, that double-door theme became an architectural feature that repeated throughout one’s tour of the factory.”

In all sorts of other ways as well, Irwin tweaked the processional experience—subtle rhythms, liminal rhymes. For example, bothered by the awkward way the walls abutted the ceiling crossbeams, he instead had them stop just short, disembodying the ceiling ever so slightly, adding to the wider sense of openness. Most tellingly, he addressed the problem of the industrial steel frame windows girdling wide swaths of the building, especially to the east, west, and south. Leaving the glass clear would have resulted in too much direct sunlight pouring in and generally drained the galleries of their focus, but frosting them (the usual solution) would have engendered a claustrophobic walled-in feeling. Instead, taking his cue from the window grid itself (with shades of San Diego), Irwin frosted most of the panes, leaving four at a time clear, a repeating sort of window-within-the-window pattern, a marvelously congenial compromise, almost imperceptible, but one that made all the difference in the world in terms of the quality of the light suffusing the space, and the wider sense of the building’s embeddedness in place. He then collaborated as well with Govan and the rest of the curatorial team in an effort to meld specific spaces, ever so gingerly, to the requirements of the specific artists being shown within them—but this last in particular ever so quietly, for Govan was having to manage a veritable menagerie of hypersensitive egos, none of whom wanted to be seen as having been placed in some other artist’s box.

So successful did Irwin prove with the infinitesimal subtlety of his interventions, and so wary did Govan and his colleagues prove (at least initially) at the prospect of broadcasting same, that when the museum finally did open, in the spring of 2003, to almost universal and sometimes virtually ecstatic praise, one of the recurrent tropes in critical response celebrated the felicity of what could be accomplished with virtually no architectural intervention of any sort, especially in comparison to the problematically mixed results (at least from the art’s point of view) evidenced in recent commissions involving such far more distinctively self-assertive stars as Frank Gehry, Richard Meier, Peter Eisenman, and their like.

I asked Irwin whether the relative lack of recognition bothered him: after all, as an artist avidly pursuing a nonhierarchical art, could he be that surprised at the nonhierarchical position he seemed to have built himself into within the art world?

“Actually, no, I’m not all that uncomfortable with it,” he replied. “I was far less bothered by the relative lack of credit I got for Dia:Beacon as a whole than I was by the fact that the little corner of the project I did keep getting credited for, pro or con, in all the critics’ reviews, was the gardens—the parking lot orchard and another garden off to the west side of the building. As if that was the only slot critics were now comfortable pegging me into. Which does get annoying.

“But, no,” he went on, “and then on the other side, every once in a while you get a piece like that review in the New Yorker.” The New Yorker of June 7, 2004, to be specific, when in the midst of surveying two recent Agnes Martin shows, Peter Schjeldahl spun out:

I thought about this at the lovely, light-drenched Dia:Beacon, a magnificent place that devotes a terrific amount of real estate and remarkable architectural skill to implementing little hits of pure aesthetic emotion. An anti-church, it offers, in the place of religion, beneficent addiction. (The hits wear off quickly. You want more.) This may be the upward limit of what liberal culture can provide for the common soul. Perhaps it’s enough. Certainly Dia:Beacon stirs grateful awe. Look at what we humans can do!

The desert of pure feeling: the apotheosis of sheer potential.

“Exactly,” Irwin concurred. “That’s all I’ve ever argued for: what we human beings are capable of. I mean, we’re quite spectacular. And the idea that our hand is turned by god or that our understanding is turned by some mystical insight or other—that’s all just bullshit, it’s so much hogwash. And yet to tell people that they’re spectacular, that they’re incredible, that they are only tapping their full potential the tiniest bit, that it’s a continuous ongoing unfurling … That’s a hard message to put out into the world. And if you attach it to—Irwin did this or Irwin did that—you belabor it in the same way as if you’d turned religious.”

God isn’t God, and neither is Irwin?

“Precisely.”

Concurrent with his work at Dia:Beacon, and in the years since, Irwin racked up all sorts of other projects, some realized, others not, several hovering tantalizingly on the verge.

In the spring of 2004, for example, as part of its minimalist Singular Forms survey, the Guggenheim in New York gave over the entirety of one its long rectangular off-ramp side galleries to a reprise of Irwin’s 1974 Soft Wall Pace Gallery installation, to dazzling effect. (One entered this version of the piece by walking up a long corridor and then forded the room at the midpoint of one of the long sides of the rectangle. All Irwin had done was to have the room painted an even white, and then on the far side, along the long facing wall, to stretch out a taut sheer expanse of his signature pearlescent white scrim, floor to ceiling, far left side to far right side, about a foot in front of the gallery’s actual wall. The initial effect could be underwhelming, since at first there didn’t seem to be anything there. But if one lingered for a few moments, the far wall would suddenly seem to dematerialize before one’s very eyes: something was there, but what? A sheer fogbank? An infinite regress? Or nothing at all? Was there even a there there? And what of the other walls: were they any more solid, any more substantial, and how was one telling? How, suddenly, was one managing to tell anything at all? And why was the ensuing vertigo of presence in itself so delicious to experience? Or, as I say, one could just miss the experience entirely. One of the further delights of the room, after a while, was to secrete oneself off into one of the side corners, unobserved, and to watch as fresh visitors arrived, this first group simply entering, blowing the room off with some giggly sarcasm, and heading right back out; while this next visitor might start to do the same but hesitate, tarrying just a bit longer, and then suddenly stagger—literally stagger, dumbfounded, gobsmacked—as the room went reeling all out of whack, the rest of the museum, the rest of the world, seeming momentarily to fall away.)

On the other side of the continent, Irwin spent months, indeed years, perfecting a new master plan for Phoenix’s Desert Botanical Garden (a favorite haunt of his, going all the way back to the days when he first began heading out into the desert), a slowly evolving labor of love that eventually came crashingly to naught. By contrast, by decade’s end it looked as though Irwin’s frequent visits to the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas—the late Donald Judd’s expansive visionary compound, an abandoned military base on the flat high desert given over entirely to the permanent exhibition of works of pure art—might finally be bearing fruit. It looked as though he was going to be given the entirety of the base’s former hospital as a staging area for a fresh permanent installation. “Seems that way, anyway,” Irwin commented, when I asked him about those current prospects, “though you never can tell.”

One permanent Irwin piece that did get realized, also in Texas, in Dallas this time, improbably involved a second unwitting collaboration, as it were, with Richard Meier, his nemesis at the Getty (in an earlier piece I’s referred to that collaboration under the rubric, “When Fountainheads Collide”). This fresh instance of de facto collaboration took the form of a private commission to slot a permanent piece into the wide lawn spreading in front of the Meier-designed home of financier and art collector Howard Rachofsky. “And that was no problem, as far as I was concerned,” Irwin insisted when I brought up the fresh Meier connection. “It was a beautiful house—homes, it seems to me, being what Meier has always done best—and this one was really nice. And that long sloping front lawn in turn provided a perfect staging area, this beautiful flat plane of geometry, for an idea I’d long been hoping to realize, going all the way back to that proposal I made in the seventies at Ohio State University. Very simple: I carved out a square in the middle of the lawn and in turn sliced that square into four internal squares, bounding each of those squares with thin blades of Cor-Ten steel and variously tilting the four resultant square planes of lawn at ever so slight cross-angles. And it worked just perfectly, playing off the wall at the far end of the lawn and that gleaming white Richard Meier house at the other. Nice and clean. And as it happens the only private commission I ever did.”

Does that surprise him, that he’d had no other?

“Not anymore. I’d have to be some kind of fool if it was still surprising me. In fact, that was the only commission Arnie Glimcher”—his longtime friend and dealer at the Pace Gallery in New York—“was ever able to get me. Or rather, I should say, that I was ever able to get him, because of course that speaks much more highly of his ongoing loyalty and support for my work than the other way around.”

Speaking of which, at that moment back in New York, Glimcher was hosting a major new piece of Irwin’s at Pace’s new annex space in Chelsea, in the old Dia annex on Twenty-second Street, diagonally across the street from Dia’s main building, the site of Irwin’s diaphanous scrim grid of a few years earlier. I’d had a chance to visit the piece just before coming out to see Irwin, and this one was almost defiantly something else altogether, almost as initially off-putting, or at any rate withholding, as that earlier scrim grid across the street had been lusciously inviting.

Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow, and Blue?3 he’d called the piece, in homage to Barnett Newman’s seminal abstract paintings of the same name (just as the earlier Dia scrim grid piece had referenced Josef Albers with its Homage to the Square3 title). And indeed, entering the vast hangerlike shed (the space where, years earlier, Dia had given Richard Serra’s Torqued Ellipses their first exposure), one was confronted with three shinily painted rectangular panels (each sixteen by twenty-two feet) spread in a receding array along the cement floor—red, yellow, and in the dim, skylit distance at the far end of the gallery, blue—directly above each of which, hanging from the ceiling, hovered three identically colored, identically scaled, identically shiny painted panels: red above red, yellow above yellow, and blue above blue. And that was pretty much it: all right, one thought, interesting, colorful, but . . . One walked about the space (the rectangles were separated by enough bare floor that one could walk among and between them), went to the far end and confirmed that yes, from that side it went blue and then yellow and then red, gleaming, shiny at the far other end of the vaguely crepuscular room.

But then, ever so subtly at first, things began to happen. (“What a slow burn that exhibit of Irwin’s is,” photographer Joel Meyerowitz emailed me a few days after I’d paid my first visit, “from a So-what to a Wowww!”) The red, for example, wasn’t simply red—or rather it was: the surface was covered over in a completely even gloss of lipstick red paint—but (had it been doing that before?) the panel was reflecting ambient conditions like crazy, so much so that in fact almost none of the surface, strictly speaking, was red. Pool-like, it was reflecting the yellow ceiling panel beyond, whose own color was in turn being affected by the blue floor piece beyond that. There were purple effects and green, a sort of even bruise-brown hovering over the entire array when one now viewed the gallery from the side. And now, ambling over to the far end and peering into the blue—and wait, that definitely hadn’t been there a moment ago—it was as if these reflections and reflected reflections were boring a hole through the floor: if there was someone else on the other side, gazing into the red, it was as if, yes, there they were, straight ahead, but there they also were—flip and counterflip—standing three stories down, and then (gazing up) three stories up as well. (The piece was as vertically deep as the Dia piece had been horizontally wide: perpendicular but every bit as heavenly.) The visitor might then amble over to the yellow rectangle, so as to peer into that pool, only bizarrely, the yellow plane afforded no such illusion: in fact one might initially assume that it had been painted with a matte yellow as opposed to the reflective gloss of the red and blue, except that on closer examination (you had to crouch down to confirm this), the yellow paint was just as glossy as the others; it just didn’t reflect the same way.

“Exactly,” Irwin said, when I now recalled my confusion. “For the same reason that—remember my thing about orange and yellow back during the line paintings? How you never see orange in classical paintings because it’s not spatial. It doesn’t open out. It’s not a window. It continues to reaffirm the flat plane, and yet it has a volume to it, you know, physically, which abstract expressionists understood. It just doesn’t go whssspt—and become a window. So that was one of the issues I was trying to play with the thing: you’ve got this immediate contradiction there—spatially, physically, tactilely … Beyond that—and this goes back to Newman’s title, and his challenge—those three colors famously present one of the most difficult challenges in color theory and color practice. They don’t want to play together. And here I wanted to tackle that challenge and to move it beyond Newman’s flat stage and in fact, as it were, to cube it, to play it out in three dimensions, and in fact in four, the fourth being that thing you were talking about, the time it takes divulging itself.”

Had he been expecting all those effects? Had they been planned?

“No, not at all,” Irwin insisted. “I’m in the same position you are, okay? It’s one of the things that happens with these things is that I have an idea about what it’s going to do, but I don’t really know what it’s going to do until we finish and the piece is up and it starts to change. You can’t mock-up something that is truly conditional. The garden was a classic example of that. Every time I go to the garden, it’s a different garden, which is one of the fascinating things about it. It’s infinitely changing. But in this particular—it is in a sense a kind of demanding—it pushes you to really use your senses, and to use them across time.”

And what of that? Why does the piece seem so flat at first? Why does it take so long to start noticing the incredibly complex infolding of colors?

“Well,” Irwin surmised, “maybe it has something to do with the title of that book of yours: Because seeing really is forgetting the name of the thing you see. In this instance, you walk in and your brain tells you, oh, that’s a red, a yellow, and a blue plane—so that that’s what you see. You see ‘red,’ and ‘yellow’ and ‘blue,’ and it takes a while for your perceptual apparatus to burn through all that initial cognitive/linguistic labeling.”

As a result, curiously, this piece couldn’t be photographed in its experiential fullness for exactly the opposite reason Irwin’s pieces usually presented photographers with such problems. With most of his other works, as he often said, the camera might approximate the piece’s image but could never convey its presence (its lived presence, which is to say the presence across time), which is to say the main thing the piece was about. In this instance, though, the camera (lacking any cognitive/linguistic filter) instantaneously captured, and couldn’t help capturing, all the complicated infolding, overlapping chaos of cross-reflecting color which it could take a person standing there a good ten minutes of patient attention to finally worry out. What a camera couldn’t capture, in fact, was the room with simple flat red, yellow, and blue rectangular planes.

“Yeah,” said Irwin, “isn’t human perception amazing?”

As we were talking, Irwin had been carefully sizing, splicing, evaluating, and resplicing various rectangular swatches of shiny red, yellow, and blue paper and then spreading the swatches out along the desk before him. For it turned out he was going to be attempting a reprise of the Pace piece there in San Diego toward the end of the coming year, at the La Jolla museum’s new downtown annex in the old vaulted train station: a differently sized shed, which was in turn going to require somewhat differently proportioned rectangles. But precisely how so? Such was the puzzle he was currently endeavoring to feel his way through.

In fact, that end-of-the-year show, a mini-retrospective as it were (which has in the meantime now come and gone, alas), was going to prove a sort of way station along the path toward a substantially more ambitious prospect Irwin’s friend Hugh Davies had been dangling for some time: a new wing of the La Jolla museum, to be designed by Irwin himself, to permanently house as complete a survey as possible of Irwin’s entire lifework. In perpetuity.

A funny idea, veritably larded in all those Irwinian contradictions.

Here he was, I started up again, hazarding a fresh new tack, seventy-eight years old . . .

“Yeah,” he interrupted, laughing. “How’d that happen? Because, honestly, I don’t feel it. I feel somewhere between seventy-eight and back in the quad at Dorsey High, and if anything a whole lot closer to the Dorsey quad. I know I’m probably working harder than I ever have, with all these projects hanging fire.”

And at the top of his game?

“I think I am, yeah. You know, because I always wondered if there was going to come some point where maybe I was going to start staggering downhill, but it seems like, you know . . . I pulled the Getty thing off, and that was really a feat, just in terms of making all those decisions I had to make: hundreds and hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of them, all of them by the seat of my pants, and it came out pretty good. Same with Dia. All these things.” His gesture encompassed his brimming table. “I guess I must be at the top of my game.”

I mentioned my grandfather—we’d sometimes talked about him—the Weimar émigré composer Ernst Toch, how he’d survived a harrowing dry patch at midlife, across the decade and a half immediately following his escape from Nazi Germany, but how then, the last fifteen years of his life had proved his most prolific. He’d been composing up a storm—string quartets, seven symphonies, a final opera—completely on fire, all the while, as he used to say at the time, under this great pressure, this tremendous sense of urgency, this need to get all this stuff out and finished before he died. Was he, Irwin, feeling anything comparable these days?

“No,” Bob replied, “not really. And honestly, I’m not sure that was even the case with your grandfather. Rather, it’s like, after all these years, you’re at the top of your game, you’re on a roll, the train is running and you’re just doing it. It’s not about urgency, about getting it all out; it’s just that you’re finely honed, and you’re firing on all your pistons.”

He paused. “Now,” he resumed, “one thing that has entered in lately, which is something that I had never at all used to consider—in fact I am for the first time being made aware of it and I find it awkward, I’m not quite sure what to do about it and haven’t had time enough to sort it out in my own head—and that’s this whole issue of history. I mean, I’ve never had any interest in history, certainly not my own, and I have almost no record of anything. Suddenly people are saying, you know, So-and-So kept all this and that—for instance, you look at what Don Judd did in Marfa—whereas me, I didn’t keep anything. My whole life I was as if stripped clean so as to be able to keep going, you know what I mean? And now Hugh starts talking about this permanent wing and this archive at the museum: it can spin your head a bit.”

He returned to some of the themes he’d first broached with me several years earlier, at the time of the MOCA/LA retrospective, the way in which (he continued to maintain) he had trouble taking his Role in History all that seriously, except in terms of this sense of responsibility he felt to be laying down a good record for the sake of future generations, the way Mondrian had, so that future artists might not have to repeat all his steps.

Even here, though, he in fact did seem to be evincing more urgency, more focus, in the way he was rehearsing those themes, and so once again I pressed him on this question of his awareness of his own onrushing mortality. After all, it was one thing to consider such things in one’s fifties, something altogether else to revisit them in one’s late seventies. You know, I suggested, for example, how some people will have a near-death experience and they will emerge from that . . .

“Oh, I had one of those,” he deadpanned, nonchalantly, rejiggering one of his colored swatches.

You did?

“Yeah, in fact a very, very near-death experience.”

When?

“Oh, back in the Ferus [Gallery] days in the early and mid sixties, when I was hanging out with Billy Al Bengston and Craig Kauffman and all those guys. I kept getting these minor infections. I was catting around at the time, so I was like, ‘Whoa, man, did I get the clap or something?’ And so I finally went to this doctor and he said—I say he said, because whether it’s absolutely true or not, since then every time I talk to one of these urologists, they’re very skeptical about this story, but this is how it came down at the time. So, anyway, this doctor looks me over and he says, ‘You have an abnormality at the exit to your bladder, a little bone spur that comes down and that bone spur has gotten enlarged and it’s blocking your passage. Now,’ he continued, ‘we can take that little bone spur out. In fact, you’re going to have to.’ Because what was happening was it was not letting the bladder completely drain and that was what was giving me all those minor league infections.

“So, I don’t know if you want to know all these details, but anyway he did this little operation, and then it wouldn’t stop bleeding. And he went in there again and he sort of cleaned it all up, and he ended up having to do it three times. After the third one I was recovering in the hospital, lying there, and there’s this bag of fluid going in and this other bag that’s supposed to be draining me, and I’m looking at the second bag and it doesn’t look to me like it’s filling, okay? So I call the nurse in, and she looks at it and says, ‘Oh no no no. It’s working fine.’ Whatever: what can you say? But the son of a bitch is not draining. So I call her in again: ‘No.’ Pretty soon, it’s getting like two o’clock in the morning and I am starting to be in real pain. Because they’re feeding water into me all the time, and nothing’s coming out and I’m starting to balloon. I call her one more time, and again she’s ‘No, no, no.’ I don’t know what the story was, whether she didn’t want to wake up the doctor or clean this thing out or what. But anyway, obviously a clot or something had gotten in there, and now I was really in pain. It’s like three o’clock in the morning and I start yelling, ‘Goddamit, get that motherfucking doctor! You call him and you get that son of a bitch in here and you get him in here now.’ Apparently, this got her attention. Because a bit later the doctor arrives and he takes one look at me and says, ‘I’m going to have to relieve you.’ And he says, ‘You’re probably going to get infected. I mean, you will get infected. Okay?’ Staph: which is a tough infection. So he does this thing and, man, I explode and pass out.

“And, sure enough, I get the staph infection. I don’t know all the ins and outs of it, but there’s nothing they can give you for a staph infection, really. Antibiotics—it goes beyond them—and also they can’t really give you anything for the pain. So my mother picked me up and took me back to the house on Verdun, and she had to pack me in ice for three weeks, day and night. I was delirious. Days would just—pop—collapse to like a few hours. People came to see me—my mother thought I was going to die. She wanted to bring the priest in—I mean the Mormon equivalent of a priest—she wanted to bring him in, and between deliriums I’d insist that, no, she not do that. She was sure I was going to die, and it must have been a close call. But basically, I guess, my system was strong enough to overcome the staph on its own, because I never did go back to that doctor.”

I was amazed. Thirty years of conversations, and he had never told me that story, and for god’s sake, I was his biographer!

“Yeah, well, it’s not something I dwell on.”

And when was this?

“Oh, somewhere in there between the early lines and the late lines.”

That absolutely crucial originary period when, to hear him tell it, he’d grown up and become a real artist? And he didn’t think this experience had had anything to do with that transformation?

“I really don’t. I mean, yeah, sure—it probably does, you know what I mean? On some level—blah blah blah—because nothing goes unnoticed in a sense. But not really, because it’s never been the sort of thing I’d dwell on: it simply wasn’t germane.”

He was quiet for a minute, thinking back, casting forward: his dear friend Ed Wortz, his old NASA buddy from the Art and Technology days in the late sixties (a rocket scientist who, in the wake of his interaction with Irwin had dropped out of the space program to become a zen psychotherapist, remaining one of Bob’s closest interlocutors all the years since), had died just a few months earlier following a long, slow illness.

“I watched Ed through the whole process of his dying,” he resumed. “He had this incurable cancer which he held in abeyance pretty much solely based on his curiosity. He really got into it. He researched it and got into the whole process, volunteering for these radical therapies. The doctors that he was working with, they loved him because he was the best feedback candidate they ever could have had. He really observed everything that was going on and reported on it. But he would get weak in the afternoon and he’d have to go in and lie down on the bed. And a number of times I’d lie down there with him. We’d actually hold hands, and he would talk about this whole process of dying. He was observing it the same way he had observed everything else, as a scientist, you know, really thinking about what it was like—what kind of emotions and feelings—and so he gave me a whole exercise in dying, in a way.”

What had they talked about?

“Well, fairly similar to what we’re talking about here, and what he and I were always talking about. It was not a fear of anything. It was not about absence. He was dealing with presence. He was all about what kind of feelings were going on right then, what kind of emotions, what kind of . . . But he really did enjoy himself. He enjoyed his life right up almost to the end. (It got a little rough there at the very end.) He was talking about the way that you don’t let go of what it is is that’s always been interesting and important to you, that the dying doesn’t change that. That dying’s just another in a series of activities or experiences. It’s going to happen, it happens to everybody, it’s not a thing to run from.”

But what about raging, raging against the dying of the light? I continued to marvel at this uncanny equanimity of Bob and Ed. Maybe, I wondered out loud (another instance of the sort of thought skipping we used to indulge in back in the days under that tree at the North Campus Library), if you think about the way death is always conceived of as a blacking out—this dying, as it were, of the light—and what with Irwin’s work so steeped in light (he is, after all, the quintessential Light and Space artist), and, yes, with California light in particular, maybe there was a burrowing connection between that light and the light of the Enlightenment, and, more specifically, that tiny light which Descartes finally uncovered deep within himself at the tail end of his own long night of radical doubt, the light of reason, which lit for him . . .

“Reason,” Bob interrupted, “precisely, which is the one thing which most clearly defines our potential as human beings. I mean, it’s even above love. It’s above all those things. They’re all nice and all, but what really makes human beings special, really special, is that ability to reason.”

That light of reason, as I was saying, deep within himself, which for Descartes was but a deep-implanted reflection of the greater light, which was the Light of God.

“Which of course is ridiculous. What did he, what does anyone need God for? Let alone know of Him? That’s just an evasion.”

(Still, one could think about the way the light of reason and the light of the world reflect one another, summoning each other forth.)

“God is just an evasion.” Bob wouldn’t give it up. (He seldom passes up an occasion to take another blissful whack at God.) “An evasion of responsibility. Even if there is a God: fine, so what? That wouldn’t replace your responsibility to act on your own unique potential. When I talk about reasoning, it’s something only an individual can do because it’s all about this idea of taking individual responsibility, it means reasoning your own being in the here and now. And that’s the most spectacular thing that human beings can do. It’s the epitome—the highest level of attainment.”

So: no God, no prospect of an afterlife . . . But seriously, what about the fate of an art whose very essence has been presence, the artist’s own being-present-to, in the face of the inevitable fact of his coming absence?

“Oh,” he said, “I don’t worry about that. Why should I? I won’t be here. And as far as the dialogue that my own striving after presence has been part of, that dialogue will go on, assuming the world goes on. Which, of course, what with global warming and all, is a matter of increasing concern.”

And what about that? He’d always shied away from political engagement, considering political art, as such, more politics than art, or at any rate a third or fourth order of art rather than the primary sort he himself was interested in pursuing. But in a world facing the sort of urgent immediate challenges subsumed under that global-warming rubric, was there a problem perhaps with such a steadfast pursuit of pure, unsullied primary art.

“On the contrary,” Bob now insisted. “Viewed the right way, that piece right now back there at Pace, the Dia in Beacon, the gardens up at the Getty are all about global warming. How can one not be aware of and concerned about all that? But it comes back to this question of human beings taking responsibility. I keep using this word ‘responsibility,’ this setting in motion your own meaning. You do that, you really do that, and of necessity you deal with global warming. I mean, the one’s a natural extension of the other. Because you take responsibility for everything. Since you are in a sense the source of all of it. I don’t mean that in any kind of spiritual or political or social way, it’s just that that’s the power of an individual. And if we don’t act on it and we don’t, in that sense, take responsibility for it, then none of that—I use these words ‘creative’ and ‘free’ and all that sort of thing—none of that means anything. There’s political history, there’s social history; there’s a political meaning, there’s a social meaning. But at the root of it all, there’s individual meaning, the source of an individual’s taking on his or her own free action, based on his or her own embeddedness, which is to say, awareness of the world. In all its dazzling complexity and immediacy and interconnectedness. In a civilization where people had been sensitized to act on that level, to be present in that way, things like global warming would be addressed immediately, they would have to be.”

I mentioned how I’d been talking to a scientist the other day who suggested that in the immediate future mankind might well be facing a choice between utopia and extinction.

“Yeah,” Bob concurred. “I think that’s true. It really is.”

The afternoon was winding down, the lightwell facing Irwin’s drafting table was filling up with dusk.

I reminded him how he often talked about not expecting to live to see the realization of the sort of world his own art was aspiring to, that such a realization could indeed still be generations off. What, I now asked him, did he have in mind? Was it (I was suddenly in a tweaking mood, wanting to dispel the mood of somber sobriety that had strangely overtaken us) a question, for instance, of not yet having sufficient computer power, such that artists in the future, properly endowed with the requisite terabytes, might be able to infuse visors with ecstasies of virtuality barely even dreamed of . . . ?

“Of course not!” Bob erupted. (I’d managed to provoke exactly the rise I was hoping for.) “The point is to get people to peel those visors off their faces, to remove the goggles, to abandon the screens. Those screens whose very purpose is to screen the actual world out. Who cares about virtuality when there’s all this reality—this incredible, inexhaustible, insatiable, astonishing reality—present all around!”