Opening a kilo of coke takes time. The outside layer of this particular package bears a colorful pattern of palm trees that makes it look like a birthday present, a thick paperback maybe. Other layers nest beneath the trees: layers of plastic, of carbon paper, of tracing and butcher paper, one stamped producto de calidad and numbered. Below the first layers, the entire brick is slathered in diesel-engine degreaser to keep it moist and mask the smell from detection dogs. Jesse attacks the package with a pocketknife and his fingers, showing neither haste nor undue caution. After all, he has done this many times before. Yet there is something about the kilo that makes it different from the rest; it is, Jesse says, the first kilo of the last shipment of cocaine that he will sell here in Pittsburgh, bringing to a close a successful career that began when he was eleven.

The kilo shucked, Jesse begins his real work: making the cut. Straight from the brick, the cocaine has a gummy texture that would prevent its being chopped into fine lines on tabletops, mirrors, and toilet lids. Jesse paid $187,000 for the shipment of seven kilos, or about $757 per ounce. Since Jesse sells ounces for a thousand apiece, he would make a profit of roughly $250 an ounce or $4,000 per kilo—a decent return. Yet, by using a proprietary recipe to double the weight of his product, Jesse will actually make more than three times as much on every kilo. Through an act of chemical prestidigitation, the seven will become fourteen and $4,000 will become $20,000. Even after Jesse treats it, the chunky coke retains a pearly sheen. “That ‘fish-scale’ shine is what you look for,” Jesse says, “but it’s not 100 percent reliable.” It matters little to Jesse that his buyers believe he is supplying them straight from the source. “They all beat the hell out of it anyway,” he says.

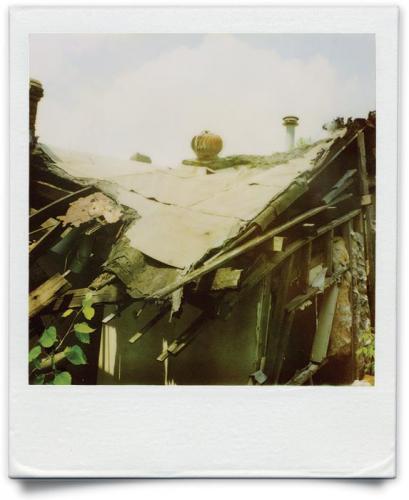

It’s hot in the attic in late July; Jesse is wearing a pair of Bermuda shorts, a carpenter’s mask, and a black bandana pulled low over his brow. (He calls it his “Hamburglar” disguise.) Just over six feet tall, Jesse has broad shoulders, though a flange of gut droops over his waistband. He sweats as he shakes the whirring grinder, fingers stained with ink from the degreaser-soaked carbon paper. Agitated molecules fly around the room. The smell of acetone and coke stain the air. “I used to get a room at a tellie [hotel] for this,” he says. “But that was actually pretty stupid. All weekend long the only thing you could hear coming out of there was the sound of the grinder: wheeeee-wheeee.”

It goes against Jesse’s instincts to have me watch what even his business partners haven’t seen. I’ve known him for less than two weeks. I’m a writer. My being here is the best measure of how serious he is about leaving.

Amid the grow lights, bongs, plastic baggies, and squeeze bottles, the attic holds hundreds of dancehall, funk, afro-beat, and hip-hop LPs, as well as turntables from Jesse’s second job as a nightclub DJ. While Jesse mixes and grinds, he has me put on records from the collection. He has only one request.

“Don’t play any roots reggae,” he says. “Because we are definitely not doing the Lord’s work up here.”

I first met Jesse at the Original Fish Market restaurant at the Westin Convention Center in desolate downtown Pittsburgh. Under a nebula of Japanese lanterns, businessmen with ties flipped over their shoulders lectured women in evening gowns. The Fish Market was a place to impress a date, to bring important clients, to celebrate an anniversary. The menu featured entrees like “Sous Vide of Label Rouge Scottish Salmon Filet” and three hundred wines by the glass. Jesse slouched through the room, his shambling walk the result of baggy jeans belted low and unlaced sneakers, tongues flopping out. Skinny dreadlocks stretched to his waist and his electric blue t-shirt bore a big print of the rapper Just-Ice. The waiters greeted Jesse by name and quickly ushered us to a table.

“I eat here like three days a week,” Jesse said. “And they know how I tip.” In his custom sneakers and designer baggies, Jesse could have been a music producer or an urban-wear entrepreneur.

At the Fish Market, Jesse may have been hitting a vodka-cranberry while sipping a fifty-dollar glass of wine, but he still knew the wine was corked and sent it back. After a flurry of text messages, Jesse announced that another guest would be appearing. “This isn’t one of my A girls,” he said. “More like the B squad.”

The B-Girl, aka Andrea, appeared and nestled into Jesse’s arm. With her soft voice and guileless brown eyes, Andrea radiated sweetness. She’d just finished a bartending shift and drained a double vodka tonic in one satisfied swallow.

“It’s like the commercial,” she said apologetically. “Vodka gives me wings.”

The waitress ran back and forth, sweat dappling her temples. A happy Jesse might pay her rent for the month. As a friend of Jesse’s put it, “He’s like Brad Pitt in that motherfucker.”

From our table, we watched Andrea walk off to the bathroom.

“They all got asses like that nowadays,” Jesse said. “I don’t know what they’re feeding them in high school. Maybe creatine and oatmeal.”

“Does she know about you?” the Mumbler said. A lanky man with ginger hair and a scruffy beard, the Mumbler favored shades of purple, lavender, and orange and looked like a cross between a candy raver and a Viking. He had brought me to Pittsburgh and introduced me to Jesse. We called him “The Boston Mumbler,” because he talked in a low tone that, combined with his New England accent, often made him incomprehensible.

“All she knows about me,” Jesse said, “is that I smoke copious amounts of trees and my paper just don’t stop.”

The gangster was talking like a gangster should. In fact, the whole night was a gangster paradise: pretty girl, fancy restaurant, fawning waiters, Jesse thumbing cash from a big roll. But I knew that Jesse had reasons to worry. The previous fall, his oldest friend had been arrested with nearly a million dollars in cash, much of it Jesse’s. Soon afterward, Jesse’s girlfriend broke up with him on the night of his twenty-ninth birthday (although Leslie still lived in his house). With his friend’s trial coming up, Jesse worried that he would be indicted too. His anxiety showed in small things. At dinner, he took two bites of his filet mignon then left the rest in a congealing pool of sauce.

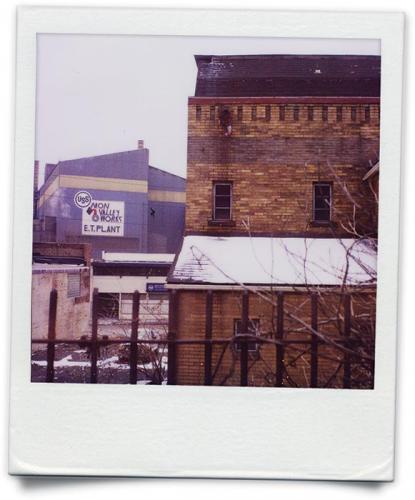

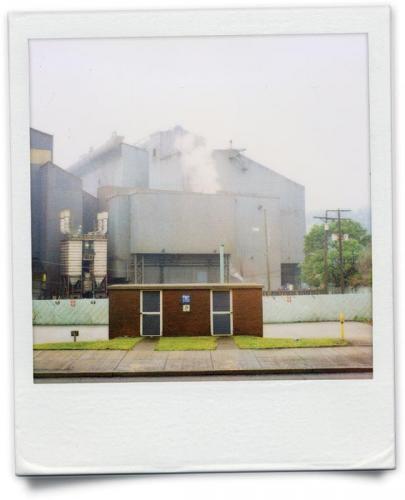

On my second day in Pittsburgh, Jesse gave me a civic tour. The Mumbler was driving. The Mumbler steered his mauve rental Cadillac down side streets and back alleys while Jesse talked. Jesse knew the drug corners, he knew the boundaries of school districts, and he knew the cost of real estate. Pittsburgh had fallen a long way from being the industrial powerhouse of history, when schoolteachers brought students to classroom windows to see coal black skies. “That means your daddy is working,” the teachers would say.

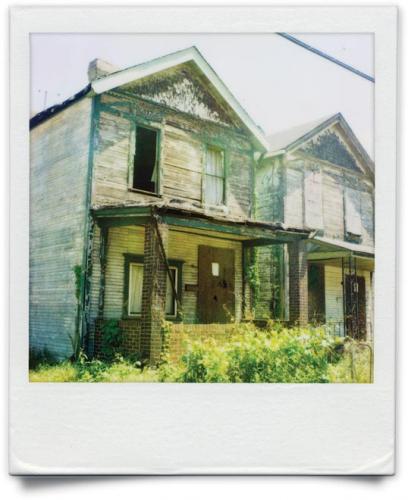

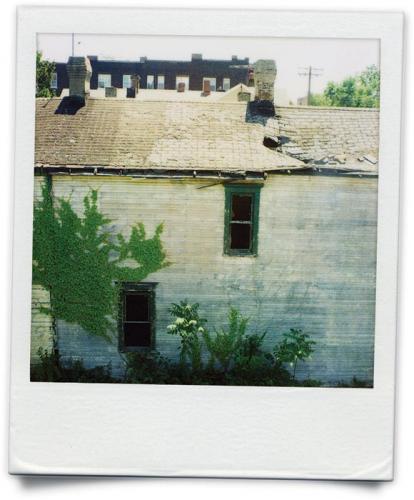

Beautiful is not a word associated with that Pittsburgh. But I loved the views from the green hills, I loved the old mansions and ornate public buildings, and I loved the abandoned warehouses and dead factories. Pittsburgh felt like a frontier: rough but with more freedom than you could find in other places.

For the same reasons I loved Pittsburgh, Jesse hated it.

“There’s nothing to do here, man,” he said. Where I saw decaying grandeur and cheap rent, Jesse saw a wasteland where crime was the only way to make money. “This town is a desert with a keg of beer,” Jesse said. “There’s nothing here for me and I was born here. This city is full of people living below their capabilities because there’s only so far you can go. All people think about is where they’re going to eat, what they’re going to drink, and who they’re going to fuck.”

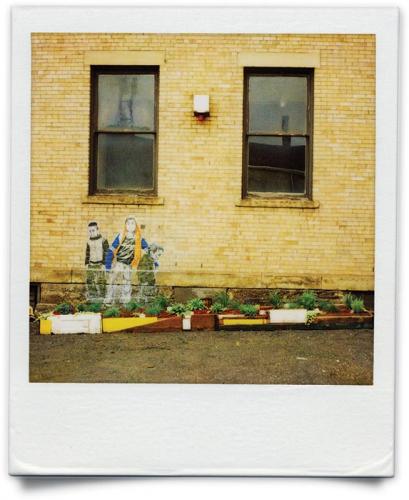

Braddock

“Look at that steel mill,” Jesse said, pointing out the Cadillac window. “It’s not running. They’re actually tearing it apart for scrap. So everyone you see working is here disassembling this bitch.”

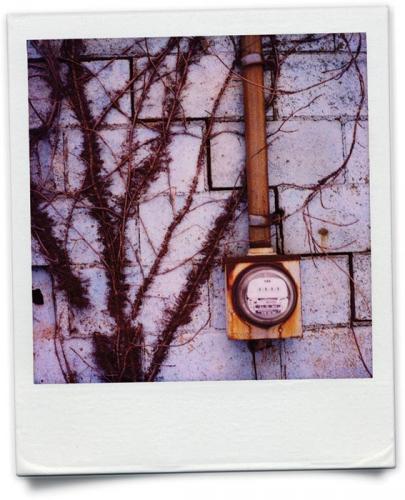

Driving the Cadillac through his old neighborhood made Jesse uneasy. Despite his gangster uniform, Jesse worked hard to lower his profile. He didn’t own a car and paid his rent in cash. Only a few people knew where he lived, he used a “burner,” and once went a full year without a phone at all. If someone got an inkling of what he did, Jesse shrugged his shoulders and said, “That was years ago. My glory days are done. I’m retired now.” Unlike most criminals, Jesse saved his money and had stashed it in safes across the city. Jesse’s caution (and luck) explained why he’d never been arrested on drug charges. Caution also explained why he wanted to quit dealing. “Look at the odds,” he said. “The jakes only have to get lucky once to ruin your life permanently. And you on the other hand, you have to get lucky every second of every single day, forever. I can’t say I like those odds.”

We couldn’t go to the housing project where Jesse grew up—it had been demolished. Instead, we drove down the empty main street.

“When I was a kid,” Jesse said, “this street right here used to be the shit. There were three fucking movie theaters on this street. You could shop for anything under the sun. Now look at it.”

He pointed to the boarded-up storefronts, to the five closed banks.

“It’s early as fuck,” Jesse said. “That’s why you don’t see the hustlers out. Don’t think they ain’t out though. They’re just in all these weird-ass little cuts. The fucking feds be down this bitch now like heavy, man. They’ll just come out here and choke you out and make you eat a laxative and sit on a bucket right in the middle of the street. I’m not even fucking with you.”

I went with the Mumbler to pick Jesse up after he put in his coke order. Jesse jumped into the car, and we slid through the empty downtown Pittsburgh night. Unlike Jesse, the supplier, or “hook,” didn’t seem at all worried about drawing attention to himself.

“He’s got a guy who tastes all his drinks for him,” Jesse said. “And another guy who cooks for him. I mean, he went right into the restaurant kitchen and made the food. How is that not going to get people talking? Meanwhile, the dude’s got eight cell phones all ringing at the same time. Hanging out with him is not a fun experience. I’m sure the feds are checking him out. There’s probably CIA guys hiding in the bushes. It’s crazy, man.”

Jesse’s supplier came from Miami to Pittsburgh for business, always taking a suite at a luxury hotel. The man’s staff—his taster, his cook, his bodyguards—was made up of old friends. “Even the brokest dude drives a Bentley,” Jesse said. Having friends act as a support staff made perfect sense. Jesse’s supplier was running a multi-million dollar operation and needed to be able to speak freely (to an extent) and relax (to an extent).

“Did you tell him you were leaving?” The Mumbler said.

“Hell no. I’m just going to stop showing up.”

“Won’t he miss your money?”

“Let me tell you,” Jesse said, “this is just a sideline for him. He won’t miss it. He’s asked me numerous times to take fifty [kilos]. And when I’m like, no, I don’t have the paper for that, he says, ‘Don’t worry, you can owe me.’ But I say, ‘No thanks.’ I’m not about to start owing this guy money.”

Jesse never made more than one order per month and never for more than he could pay with cash on hand—usually five to fifteen kilos.

The supplier had told Jesse that the shipment would arrive the following Wednesday, at which point he would call Jesse. The money and the drugs were never in the same place at the same time.

“How do you know the hook?” The Mumbler said.

“I’ve known dude a long-ass time. His old man used to buy herb from my dad. He never liked me but he knows me.”

Jesse’s paternal grandfather was a West Indian numbers runner who committed suicide. His mother was the illegitimate daughter of a respected jazz musician. Jesse’s father was a hustler. Some of Jesse’s earliest memories are of bales of marijuana on his kitchen table. Jesse’s father made up for his infrequent visits home by knocking his son around. As Jesse put it, “He was into some crazy tough-love shit. Once he punched me in the chest so hard that I flew across the room and knocked over the refrigerator. I remember thinking, ‘Well, nobody my own age is going to hit me like that, so I got nothing to be afraid of out there.’” Along with beatings, Jesse’s father provided entrepreneurial advice. “He told me: ‘You’re not selling the product. You’re selling yourself. Remember that.’ I think I was like nine at the time.” Otherwise, Jesse’s father kept out of his son’s life. “I hated that man until I was twenty-nine years old, but he raised me just like he was raised,” Jesse said. “Now I realize that he was giving me the tools I needed to survive.”

Because of federal anti-racketeering laws, Jesse didn’t spend much time with his father. “I don’t need to have no RICO charge come down on us,” Jesse said. Jesse’s father had never involved his son in his illegal activities. When Jesse started dealing, it was entirely on his own initiative. Jesse discovered his calling in the third grade when he started selling candy at school. “I used to flip candy and shit,” he said. “Those rich kids didn’t know how cheap it was in the ghetto.” At eleven he turned to a more profitable Braddock staple: crack cocaine.

“I had thirty-five dollars and I wanted to make more,” Jesse said. “I’m dead-ass serious with you. So I bought what they call a double up and I just kept doubling it. Crack was everywhere. I was on the street, know what I mean? If you’re outside all day, even at six years old, you know the motherfuckers who got whatever. It’s not hard to tell the pimp. It’s not hard to tell the dude selling crack.”

Calculated risk taking, calm under pressure, and an ability to identify markets and suppliers: Jesse was a model businessman. At fifteen, he found a source for low-cost, high-quality marijuana: a hippie supplier in Vermont. Too young to drive, Jesse would ride Greyhound dressed as a soldier, going so far as to shave his head and bring the marijuana home in an army duffel bag. When the hippies began to treat him poorly, Jesse robbed them, carting away a trunkful of marijuana and cash. Jesse didn’t mind ruining the connection, as he’d already identified a better source: an Indian reservation on the Canadian border.

Yet Jesse had problems with his new supplier. “You got green berets up that motherfucker,” Jesse said. “You got border patrol and the res cops and you got the fucking UN police because of the terrorism shit.” There were also state police roadblocks just outside the reservation. Jesse found the Indians to be unreliable business partners. “They don’t like anybody,” he said. “Anybody. They’re still so pissed off that motherfuckers took their land. And on top of that, there’s no organization. Them sneaky crook fucks will fuck their own brother over.” Jesse managed the Indians by bringing them a drug that wasn’t available locally: cocaine. “You talk that ‘soft’ shit to ‘em,” he said. “Oh my God. They’ll fucking shoot their mom in the fucking forehead to get it.”

The reservation made Jesse as a dealer. The marijuana was cheap, high quality and abundant. “We were doing like three hundred [pounds] a weekend,” Jesse says. Soon the issue became finding someone to smuggle the drugs. Everyone was getting rich, and with money came caution. “So you can’t talk to the broke dude,” Jesse said. “Like, we know you need some money, so you’ll do it just because you got to.” They solved this problem by bribing the owner of a salvage yard near the reservation. Jesse would pack wrecked cars with marijuana. The cars would then be loaded on flatbeds and driven to Pittsburgh. As Jesse put it, “Who’s gonna fuck with the local dude who they call every time they tow a car?”

As Jesse got older, he dumped his money back into the business. Having a cash reserve meant he could wait for the best connection and buy bulk at the lowest price. With the Indians, Jesse found himself doubling and tripling his money until the money became a headache and he had to cram it into the succession of safes. As crazy as the reservation might have been, the money was good and nothing ever happened bad enough to make Jesse stop. “We did that shit for eleven years,” Jesse said, “and we never lost a load.”

Jesse preferred selling the high-grade marijuana to cocaine because the risk/benefit ratio was lower. “Clip me with a three hundred pack of weed,” Jesse said, “What’s that gonna do? Motherfucker, I’ll only do six months. But if I get hit with three grizzles [grams] of coke, I’m fucked. Especially if you have it in separate plastic bags.” But in that bad winter after his friend’s arrest, Jesse turned to cocaine. It started when Leslie’s mother complained about the quality of the cocaine she was selling to supplement the income from her hair salon. “I told her, ‘I can probably help you out,’ and I talked to some people.” Leslie’s mother also gave him the key ingredient to the recipe for his cut. Jesse’s entrée into the market came during a citywide cocaine drought and customers lined up. As Jesse said, “Shit ain’t worth dick if everybody got it. Sometimes I’ll pretend like I don’t got shit for two weeks. Just so I can charge a fucking hundred bucks more. Per clip. You do that three, four hundred times, that’s another fucking forty grand.”

“I’m just a piece of trash from the gutter,” Jesse told me with pride. “I was born to be what I am. I come from a family of hustlers. Know what I mean? Most people at family reunions. They talk about their kids and who got married and shit. At my family reunions, everyone talks about how much paper they made on their last hustle, and how bad they fucked somebody up.”

One night, as Jesse waited for the cocaine, he bought seven pounds of marijuana and brought it to Scooter’s house. Scooter was a big man with an even bigger beer belly and upholstered with tattoos. One of the biggest tattoos stretched across his gut and read, lunchbox. (Scooter had lost a bet.) I assumed he was in his forties, but he said he was only thirty-one.

“That’s not what you do Scoot,” Jesse said. “You got to peel the shit . . . ”

“I peeled it,” Scooter said. “And then I broke it up.”

“No, roll it around in your hand and shit so it breaks up.”

We were sitting in Scooter’s filthy bedroom where Jesse had opened the box full of midi-brick marijuana. “Midi” referred to the middling quality of the marijuana and “brick” to the fact that it had been compressed before shipping, probably in a trash compactor. Jesse was giving Scooter a lesson on separating the sticky marijuana buds.

“I peeled a piece off,” Scooter insisted, “and I broke that up.”

One of Jesse’s uncles had called a few hours earlier looking to get rid of the midi. Jesse knew someone who would buy midi and the deal was made. Now Jesse was separating the buds in an attempt to get more money out of his buyer. Separating the buds helped to restore them from their compressed state. While compression made the marijuana easier to transport, it diminished potency. The buyer would still know that it had been compressed, but if the buds looked good, he might decide that he could do further work and sell them for a higher price. (There were techniques for restoring bud volume involving humidifiers and steamers.) Breaking the buds only created “shake”—loose shreds and flakes.

Jesse’s cocaine order was supposed to have arrived a week earlier. The midi was an opportunity to make a few thousand dollars while he waited. Jesse wouldn’t even smoke the midi—“That crap gives me a headache,” he said. But money was money.

Jesse slowly parted two buds.

“See how it’s like pieces?” he said. “Peeeel it. Peel each piece. That’s the only way it’s going to pop back. It’s not going to make any difference if you just break the chunks into smaller chunks. See what I mean? They’re actual fucking buds that they just laid in the bitch.”

Scooter shook his head. When it came to drugs, he remained an earnest amateur. Scoot was part owner of the Darkside Lounge, a bar that provided most of his income. He referred to the money he made from coke as “play money.” Scooter used the play money to take women out, buy gifts and, when he was inebriated, emphasize whatever point he happened to be making by tossing handfuls of the money at you. The Mumbler had told me that Scooter’s father had been in the Mafia and died young.

“I didn’t break it like that,” Scooter said.

“I just watched you do it,” Jesse said.

Scooter had first gotten to know Jesse as a fellow DJ. Only after Scooter bought the bar and Jesse made it his hangout did the two start working together.

“This job sucks,” Scooter said.

“You wanted to be number two,” Jesse reminded him.

The front window of the Darkside Lounge, which served as Jesse’s de facto business office, displays a carved metal panel of a skeletal mummy, a lean body lifting a serving tray overhead. The central cadaver is flanked by two smaller ones, also lifting trays, one of the bodies curvedly female. Piled on the trays are glasses, bottles, and philters adorned with tiny skulls, while sphinxes rest at the diabolical waiters’ feet. The semi-Egyptian motif continues inside: on the bar, table tops, and wall murals painted rust and gold, all the mummies with the same fleshless heads and bony jaws. In every skull, one eye socket is set higher. The lower eye is circled like a bull’s-eye, making the skulls look cock-eyed and bewildered. The mummies gape from the bar, from tabletops and from their graven posts in the metal dividers between booths. They drink. They smoke. They slump over tables. The artist who designed the bar, a notorious alcoholic, appeared in the Darkside from time to time, a ghost in his own creation.

After his connection called a week late, Jesse waited forty-eight hours before picking up the coke, demonstrating that he too could play the waiting game. The coke was at the house the connection had bought for his Pittsburgh mistress, and Jesse drove there with Andrea after another long night of drinking. Andrea waited in the car, happy and oblivious as Jesse ran inside and came back with the seven kilos in a paper bag. “She’s too dick drunk to realize anything,” the Mumbler said. Jesse then stashed the shipment, except for the kilo that he took home to cut and sell.

At the Darkside, Jesse’s crew clustered in a corner chugging Jägerbombs, a noxious concoction of Jägermeister and Red Bull. Atash Khan (nicknamed AK) delivered a mock-diatribe against Jesse, who was DJing across the room, the speakers blaring a guttural dancehall declaration from Sean Paul: “Woman, she want to bang.”

“My toupee smells like Newports because the fake Jamaican with the jheri-curl was blowing smoke at me for thirty minutes,” AK said.

Everyone laughed. Cocaine had brought happy days again.

“I need a shot,” AK yelled. “Bring us another round, Lunchbox.”

Scooter manned the bar and although the name was given in jest, he was quick and efficient as he scooped ice and flung drinks. In a previous incarnation, Scooter had been a high school teacher (and an internet reverend). From time to time his former students would walk in and do a double take. “Mr. Alberti,” they’d say, “What are you doing here?” Scooter had bought the Southside bar for a wealthy investor who thought a DJ’s connections would be good for business. The investor had ended up becoming Jesse’s customer. “I’ve made copious amounts of money out of that establishment,” Jesse said.

The crew rendezvoused at the Darkside, on a long strip packed with bars and clubs. On the weekends college kids wearing the inevitable Steelers gear filled the streets shrieking, fighting, and puking on their shoes. The Darkside made money on the nights Scooter had bands or themed DJs. The rest of the time, it was just regulars. “There’s nobody in that bar who isn’t part of the family,” the Mumbler said and while that was an exaggeration, the same faces turned up all the time, to the same backslaps, handshakes and conversations.

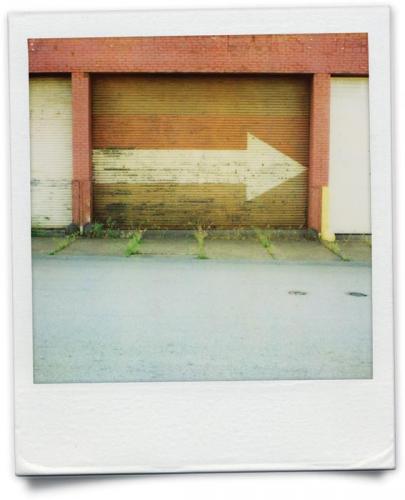

If you needed to find Jesse, you went to the Darkside. Some nights he could have nine or ten business meetings, transactions that couldn’t safely transpire on cell phones. No money changed hands at the Darkside, certainly not any cocaine. As the actual exchanges were the most dangerous part of the business, they took place quickly. A few vague comments on the phone. A quick exchange of drugs and cash in a bedroom. They were all magicians—now you see it, now you don’t. Jesse’s “downline,” the people who distributed his coke, consisted of two groups: members of his crew and old connections from Braddock. The boys from the hood stood out a little in the bar, dark and quiet, with no hipster accent marks to their gangster vines. Those old friends lingered only long enough to have a drink and make arrangements. “I left the hood six years ago,” Jesse told me, but keeping the lines of communication open was lucrative.

When Jesse moved away from Braddock, he left behind turf wars and gangs. (On the Pittsburgh bar and club circuit, it was every dealer for himself.) Living near a college campus and hanging out with students had been a revelation. “I thought, ‘This is a lot funner than the hood,” Jesse said. Jesse allowed his crew to buy the coke on credit while the hood guys paid cash up front. Who they sold to was no concern of Jesse’s. He was insulated; his downline would never say where they got the coke because it would give customers the chance to cut out the middleman (and infuriate Jesse). If the system worked, the drugs never stayed in one place for long, spreading in mere hours through a chain five or six or eight people long until it reached the college students, artists, bus drivers, and office workers looking for a thrill. Except for Scooter, none of Jesse’s crew even used coke. (Marijuana was another story; Jesse smoked a quarter-ounce a day. “Trees is my Paxil,” he said.)

Jesse took a break from spinning to buy a round and tell stories of AK’s misdeeds.

“So I get a call from AK,” Jesse said. “He says, ‘Call my mouthpiece. I think I’m going to jail.’ And I said, ‘What makes you think that?’ And AK’s like, ‘Because I’m in the back of a paddy-wagon in handcuffs!’”

The laughter continued. Blind drunk, AK had totaled his car on a median strip and then taken refuge in his girlfriend’s house. However, the police had tracked him down , and after surrounding the apartment building, shouted through a megaphone, “Atash Khan. We know you’re in there! Get your fat ass outside right now!”

AK lowered his head modestly and snickered.

AK was flush, flinging cash from a roll that he plucked from one baggy pocket. His thick body had ballooned from excess, vanity bringing him to wear over-sized floral prints that draped him like drop cloth on a boulder. Jesse had met AK when they were both sixteen. “This guy I knew told me I could trust him,” Jesse said. “So I dropped off some work at his house. He was already somebody’s mule way back then.” AK’s exploits spanned wrecked cars, multiple arrests, and bottles of Louis XIII guzzled like Bud Light. Since his only source of income was hustling, AK was entirely reliant on Jesse. Before the shipment came in, AK hadn’t been able to go out unless Jesse paid his bills. “I think he’s got twelve dollars to his name,” Jesse said. I’d overheard AK harassing Jesse about the shipment the week before. If AK didn’t supply his customers, they might find another connection or decide they could keep owing him money. “I like to put my people on ice sometimes,” Jesse said. “That’s when you see what they’re really all about.” Yet the wait, as Jesse well knew, had squeezed AK.

Jesse didn’t want me sleeping at his house, but the Mumbler convinced him to put us up for a few days. On the first night there, I opened Leslie’s bedroom door while looking for a bathroom. I thought nothing of it, but Jesse became convinced that I’d been trying to . . . actually I’m still not sure what, steal Leslie’s underwear? While I slept in happy ignorance the Mumbler stayed up until 6 A.M. persuading Jesse that hitting me with a baseball bat was not an appropriate response to my mistake.

It was hard to call Jesse paranoid, since it helped keep him alive and out of prison. Yet the marijuana he started smoking before breakfast, his “Paxil,” made him even more suspicious. “This is not your granddaddy’s reefer,” Jesse said before I took two drags of it one night. The resulting paranoia had convinced me that the Mumbler (a) had secretly copied my notes and voice recordings, (b) was an FBI informant, and (c) was using me in a sting operation.

Obviously I’d seen too many detective movies. Yet there was a kernel, a germ, a cell of truth to my paranoia about the Mumbler. The man was always working an angle. He lived to hustle, thrived on conflict. His feet would shuffle in delight as he told an airline that he wondered how they would repay him for wasting his time, advised his cell phone company that they owed him a free Blackberry, listened to the car rental company beg him to return the Caddy. I never got to bed earlier than 3 A.M. in Pittsburgh because the Mumbler insisted on driving from hotel to hotel to negotiate the best possible room rate. The Mumbler had originally wanted to shoot a documentary about Jesse leaving Pittsburgh. He couldn’t do that though, because the film would have ended with everybody going to prison. Instead, he had to settle for me. I’d generate the raw material for a film, the film that Jesse would help develop and finance, launching their partnership to Tribeca, to Cannes, to Hollywood.

Jesse had to trust the Mumbler to bring him into a new business in a new city. Trust that he could invest money in a film production business that as far as I could tell had only lost money. That had a number of projects “in development.” Meanwhile the Mumbler was already pressuring Jesse for money, to show that he was ready to be a partner. Trust was necessary. Trust between two hustlers. Trust from Jesse, who had an understandable tendency toward paranoia bolstered by day-long applications of not-your- granddaddy’s-reefer. Not to mention that Jesse’s idea of investment was putting cash into a safe. “I still have the very first stack I ever made,” he said. Jesse was supposed to leave Pittsburgh with the Mumbler after a week, maybe two. But two became four became six and Jesse showed no sign of going anywhere. He was making too much money.

Too much money explained why we were speeding down the interstate in West Virginia at eight on a Sunday morning, hip-hop booming, the cab hazy with marijuana smoke. On the green slope of a copse, a cantering deer stopped and looked up at the roadway, part of a natural order a million miles away. From the car speakers Nas intoned, “I never sleep / ’Cause sleep is the cousin of death.” AK looked back at me as he sang along, attempting to impart a valuable lesson to me. I was the only one who slept the night before—a luxurious total of two hours. I didn’t mind the criticism, but felt uneasy with AK taking his eyes off the road, as he was very stoned and had been drinking steadily for twelve hours. In the front passenger seat, Jesse rolled marijuana and tobacco in what was commercially sold as a blunt–cigar wrapping paper (cherry-vanilla flavor). Next to me sat Mazzoni, Scooter’s main client, a bar manager who was still recovering from a .45 slug he’d taken to the belly five months earlier during a robbery. While Mazzoni claimed the gunmen weren’t customers, I’d been told that he was selling cocaine at the time. Mazzoni had only an uncertain notion that the man sitting in front of him was the source of the drugs that had gotten him shot.

All things considered, AK was doing an excellent job of driving, although I still couldn’t help but clutch the handhold over my window. In the rearview mirror, I could see the Mumbler’s Cadillac. At a rest stop, the Mumbler complained that he kept falling asleep at the wheel. Jesse had started distributing the coke a week earlier, and the crew had been out partying every night since. Mazzoni thumbed through a stripper magazine he had picked up the night before and there was a shouted discussion over the merits of West Virginia strip clubs.

“This one,” Mazzoni said, “has Jacuzzis in the rooms. How about that? A strip club with Jacuzzis! Maybe we should skip the casino and go straight there!”

The decision to make the trip had been reached at Scooter’s. Various locales were discussed—the Bahamas first, then Vegas and Niagara Falls—only for the consensus to settle on a casino/dog-track in Wheeling. Jesse said he was banned from West Virginia—something to do with armed robbery and a high-speed police chase as a teenager. (He earned his GED in the Beckley Federal Correctional Institution.) But the inducements were too good to pass up.

“We can get straps here!” Jesse said. “All poly-carbon straps. Right up in a town over that hill. To defend ourselves from all these crazy rednecks!”

The ride floated on a wave of intoxication. Jesse had opened the taps and the money was flowing. It was a demented version of the corporate excursion: the celebration of a successful sales cycle and establishment of team solidarity. For AK it provided a chance to smooth things over with Jesse after their conflict over the coke. For Mazzoni it marked his entrée into the inner circle, the closest he’d come to hanging out with the boss. As the Mumbler phrased it, “This dude is so blown out of the water now because he thinks Jesse might put him on.” With a bar to run, Scooter had stayed home.

Jesse needed a crew for the same reasons his supplier did—a crew meant people he could relax with and party with, people who made what he did seem normal. The crew also helped him distribute the coke when he was ready. Yet, having a crew meant managing a group of full-blown sociopaths, men who’d become involved with drugs precisely because they didn’t like being told what to do. It meant dealing with Scooter’s mistakes and AK’s alcoholism.

One way Jesse played boss was by paying for everything—for all the food and drinks (no small sum), for the hotel rooms, and even for the strippers, passing out bills at the stage and buying lap dances all around. Jesse made everyone feel like they could never have as much fun with anyone else. Jesse was funny, he was smart, he knew the bartenders and pretty girls—he had charisma. Money brought the crew together, but it was Jesse’s charisma that sustained loyalty through the dry months, the arguments, and the legal threats.

At the casino/hotel we rented adjoining suites and collapsed. Upon waking, I found AK disconsolate at having been left asleep while the rest of the crew went shopping. (They had left Pittsburgh with only the clothes they were wearing.) AK was hungover, sleep-deprived, and angry with Jesse.

“We came down here on the humbug,” AK says. “And now I’m standing here in the hotel room while those guys are out doing who knows what the fuck. Waiting for fucking Jesse to tell them what the fuck to do and he’s standing there saying, ‘Dude. Dude. Know what I mean?’ He’ll say, ‘Know what I mean?’ twelve times and they’ll all nod their heads. It’s like Entourage with Down’s Syndrome.”

Minutes later, the rest of the crew returned with good news. The dog track and a strip club were on the other side of the parking lot. AK glowered and started complaining, but Mazzoni cut him off.

“We brought you something,” Mazzoni said, and presented a fifth of Jack Daniels. AK’s eyes lit up.

“I’m tired of all this talking,” he said. “Can we blaze?”

Another blunt circulated, but it proved too much for AK, who retreated to the bathroom where we heard him vomiting. He walked out wiping his mouth.

“My stomach lining is floating around in there,” he said.

Jesse walked into the bathroom.

“You got an ulcer,” he said. “I got one too. You have to take care of that shit.”

That night after a sojourn in the strip club we returned to the casino to find all the restaurants closed. Jesse and I tried to make a meal out of the vending machines, settling on sticks of salami and cheese. In the elevator Jesse looked gray and drained. He had only taken off a few nights in the last three weeks and none for the past seven days.

“I’m tired of this,” Jesse said. “I miss my girl. We’re meant to be together but it’s not working. I used to go home every night because I had something to go home too. Now I got to watch the woman I love out binge drinking and starving herself, destroying her life.”

When it came to women, Jesse only talked like a gangster. In practice, he was domestically inclined and supported his mother and his six-year-old daughter. (“My daughter,” he said, “is a love child.”) For Jesse money wasn’t enough. Unlike his father, his uncle, AK, and his supplier saying “fuck it” to the future, Jesse wanted something else. “I want to do something,” he said, “that my daughter can be proud of. Know what I mean? I don’t want her saying, ‘My daddy is a drug dealer.’ I want her to say . . . something else. I’m just tired of this shit,” he said. “I mean look at AK. All I’m doing is making him money and all he does is fucking stress me out.”

Like everyone I knew who chased money—the investment bankers and corporate lawyers, the ad men and TV execs—Jesse was sleep deprived and prematurely aged. Yet in his unregulated business, Jesse could lose a lot more than money.

“Jesse got arrested,” the Mumbler said. “He’s in jail.”

I’d woken up to a half-dozen missed calls from the Mumbler, and those were his first words.

“What happened?” I said, thinking that the feds had grabbed Jesse, that he got picked up with drugs, that after nearly two decades spent negotiating a high-risk profession his luck had run out.

“It was for domestic violence,” the Mumbler said. “Leslie called the cops on him.”

“She did?” I said, trying to remember the night before. There’d been the usual excess at a bar on the waterfront, then a party at which Jesse had kicked apart a table and wrestled on the floor. The last thing I heard as they dropped me off was Jesse saying he wanted to go home too.

“Did they find anything?” I said.

“I don’t know,” the Mumbler said. “But they were in his house. You know what he’s got there. You know what the third floor looks like. That place even smells wrong. Jesse’s getting sloppy. There are all kinds of things that cops should definitely not be seeing. I got to get in there somehow and clean up, if they haven’t locked it down already.”

The Mumbler was furious. Leslie had violated the most important rule of their world.

“That girl,” he said, “showed that she is a total fucking amateur. No matter what happens, you never call the police. I don’t care if he broke her arms and legs. You do not make that call.”

The code was clear: Leslie knew exactly what Jesse did and had benefited from it for years. The police were no longer problem solvers for her, only problems.

“If something happens to Jesse,” the Mumbler said, “I’ll shoot her myself.”

As it turned out, Jesse’s bail had been set at the nominal figure of five hundred dollars. The police didn’t find anything. I had seen the gangsters at their worst, but the arrest showed them at their best. Living, as they did, in a state of perpetual crisis (usually of their own making) a new crisis was nothing out of the ordinary. In fact, the crew was designed to manage crises, and they dealt with the aftermath quickly. The following Monday, Scoot took Jesse to the bail bondsman and handled the paperwork. Later that day, they met AK’s lawyer and planned a strategy for the hearing.

The Mumbler focused on Leslie. Complicating negotiations was the fact that Jesse couldn’t speak to her directly because of the charges. Leslie’s behavior alternated wildly. First she said she wasn’t going to press charges. Then she said she would. She pointed to a large bruise on her thigh as evidence, but a dozen people had seen her tumble down a flight of stairs in a bar the same night. “Stop acting,” Jesse said. “You ain’t gonna win any awards.” Even Leslie’s mother took Jesse’s side. Jesse showed little anger, even though Leslie had swiped the SIM card out of his phone and texted every woman on it with comments like, “Slut whore, your man is in prison. What are you going to do now?”

After three days of pleading, the Mumbler got into the house and made it legal. When he left, the trunk of the Caddy held enough contraband to open a black market. Four thousand dollars of Jesse’s money had disappeared, a theft that the Mumbler laid on Leslie. (Jesse suspected the Mumbler.) The stash went into the basement at Scooter’s, which was hidden beneath a trapdoor in a closet, a relic of Prohibition. With the house emptied, the danger faded. “So basically,” Jesse said, “I had a six thousand dollar argument.” Jesse had supported Leslie from the time she was twenty. “What am I going to do when you leave?” she’d said the day before the arrest.

More than ever, Scooter’s house became the base of operations. People walked in and out at all hours, parties raged through the night, and sacks of cocaine flew through the air. After tossing eleven ounces to a grinning AK, Jesse nodded. “That man,” he said, “has been doing crazy work for me.” Jesse had finally decided to leave and his imminent departure had quickened the business tempo—it was time to make money.

Jesse had never held a straight job, paid taxes, or opened a bank account. “I’ve never put a dollar into a bank,” he said. “Ever in my life.” In Pittsburgh, Jesse was powerful; anywhere else, he was a blank résumé. Not that he planned to leave forever—money remained in the safes, and he had to attend PTA meetings. Yet he had decided to stop dealing and make New York his home. His crew would have to fend for itself. “I told them,” Jesse said, “do as much work as you can. Stack the money that you’re making.”

“To tell you the truth,” AK said in the last days, “I’m not trying to have Jesse leave right now.” Scooter had his bar; but if AK wanted to keep making money, he’d have to find another source, as Jesse had no intention of introducing anyone to his supplier. “You can’t cop from my hook,” Jesse said, meaning that his connection would never agree to meet another agent. Even if it was possible Jesse wouldn’t do it. “Why do I got to fucking put you on?” he said. “Why do I got to make it so that you get wealthy? Nobody fucking helped me.” The connection would always be there for him in case New York didn’t work out.

On his last day in Pittsburgh, Jesse waits at Scooter’s for his last customer. He leaves the house for a quick meeting and soon afterward the customer storms in. Although it’s not quite three in the afternoon, the man is already drunk and loud with beads of sweat on his bald head. He says he’s been drinking and smoking crack since 6 a.m. He says he can get quality prostitutes at a low price.

“I got three girls in the car right now,” the bald man says. “They’re dying for this soft.”

Scooter ushers Baldy out of the living room. In a few minutes, Baldy reappears.

“These girls are wild,” Baldy says. “We’ll be going all day. Give me a call if you want to hang.”

When Jesse gets back, we tell him the story. He shakes his head.

“That motherfucker is crazy,” he says and smiles. Baldy isn’t his problem any more.

“If he gets busted and rats me out,” Scooter said, “I’ll fucking kill him. Or I’ll have him killed.”

We leave Scooter cursing in the street and head for the freeway, the Caddy stuffed with Jesse’s LP’s, turntables, clothes, and two pounds of marijuana. In the car, Jesse can’t stop talking about his new life. He’s going to relax. He’s going to take film classes. He’s going to hit the gym every day.

“I’ll be so ripped,” he says, “the only thing I’m ever going to wear is a beater and khakis. You’re going to have to beg me to put on a shirt.”