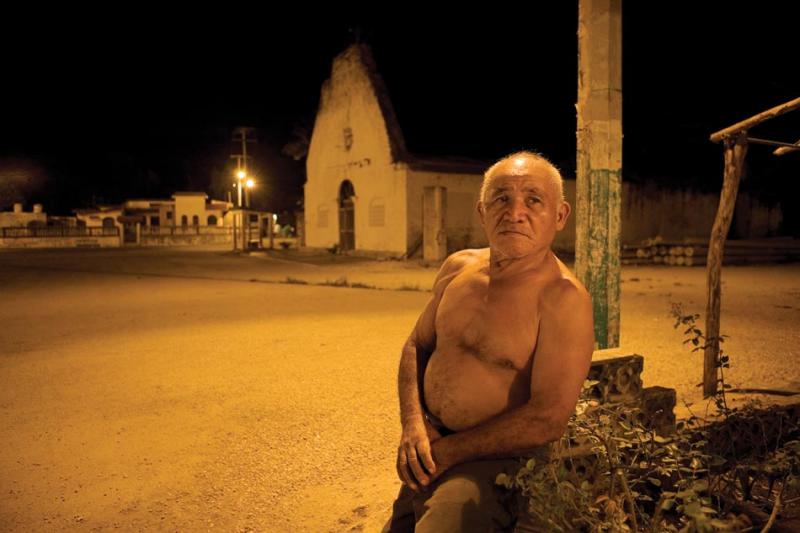

As far back as anyone can remember, the tiny Mayan pueblo of Pocoboch did not exist to the world. And the world barely existed for Pocoboch. Over the centuries, a handful of outsiders managed to find the jungle village hidden in the center of the Yucatán Peninsula: colonial Spanish missionaries bestowed on the town a rustic adobe chapel—although not even the eldest of the remaining old men has any idea when it was constructed—and on the people a fierce religiosity, expressed in neither Castilian nor Latin but the Maya that, much later, Mexican government teachers would labor so vigorously to eradicate. But even few missionaries were zealous enough to venture here.

Afflicted as it was with a landscape of tendrillar jungle flora stretching in steamy layers toward a turquoise sky forever dotted with cumulous clouds, Pocoboch was a village from which even fewer people escaped. A town so sequestered that forty-one years ago, when Eduardo Romero Martín turned twenty-three, the farthest he had been was the neighboring town. The journey in those days, on the only path out of Pocoboch, required a three-hour trek through the ensnaring monte; now it is a ten-minute school bus ride for Eduardo’s seventeen-year-old daughter, Geidy. That young Eduardo traveled the path so often was less out of restlessness than his shy infatuation with Ada María, the round-faced daughter of a storekeeper. Her face still girlish despite the thin streaks of white in her hair, Ada María flashes her devilish smile when she talks about Eduardo stealing her away to Pocoboch. That smile only disappears when she speaks of the family’s downfall—for which the land, international politics, and climate change are to blame—or of her and Eduardo’s careful efforts to shield Geidy from their own childhood suffering.

In Eduardo’s boyhood, Pocoboch was still a lush, tropical oasis. While there was no running water or electricity, the villagers were blessed with terra-cotta soil so fertile they scarcely needed to gather in the jungle in the summer for the nine-day prayer to the gods for plentiful harvests. Rain was so predictable, Eduardo recalls in bitter awe, that campesinos knew precisely which day to sow before the spring downpours, and so abundant that toads sang from the monte at all hours. The village remained perpetually damp, the plaza filled with puddles and roaming pigs, and the paths separating the scattering of wood-and-palm-roofed palapas were little more than eternal swaths of mud. After his two years of schooling—in which the teacher spoke nothing but Spanish, and the twelve pupils nothing but Maya—Eduardo took up the destiny ordained to the people of Pocoboch: growing yucca, squash, tomatoes, chiles, beans, and corn on small plots carved into the jungle, first to help feed his parents and nine siblings, and then his own wife and four children. There may not have been much money, but for most of Eduardo’s lifetime, the corn made the town run. And then, simply, it did not.

We sit at the kitchen table of Eduardo’s squat cement house at the corner of the plaza, shrouded in a spray of brilliant lavender bougainvillea, as he unfolds his story in slow Spanish accented with the hard consonants of Maya. It is a story repeated, with minute variations, in millions of families across Mexico. The story of a government so uninterested in its multitudes of rural poor that it charges fees for parents—many themselves illiterate—to send their children to school and then fails to create jobs, so that young Mexicans have no choice but to flee their pueblos. It is the story of a government which favors American businesses with massive tax breaks while families of Mexican farmers starve, and which denies nearly 25 million poor subsistence farmers access to water other than that falling from the skies, while running pipelines to the arid fields of rich agribusinesses. It is a story increasingly being repeated, too, across the developing world, as poor nations begin to pay the environmental price for the First World’s appetite for energy—not just the flood-ravaged coast-dwellers and islanders threatened by rising seas, but, more silently and pervasively, a story of spent lands, failed crops, and slow, but forced, migrations.

Although the kitchen door is open to the village square and the streets are empty, it takes us a few minutes to register that it has begun to sprinkle. This is the first rain, Eduardo says—for he has been counting—since a drizzle forty-seven days ago, and only the second rainfall the jungle village has seen this year.

Across the developing world, from Haiti to sub-Saharan Africa, massive swaths of land are quickly becoming too parched for human habitation, with nearly one billion people already affected by a combination of poor land management and climate change. In a country of vast ecological diversity, more than half of Mexico’s surface has already become too spent and arid to produce crops—a process called desertification—and every year another 250,000 hectares, the spatial equivalent of a megacity, become desertified. Despite being largely tropical, the Yucatán is at particularly high risk. A recent UN study predicted that, while water availability will decrease in all of Mexico, Yucatán will be especially hard hit—given its exposure to hurricanes and soil ill suited for rain-fed agriculture. Over the past few years, the impacts of human error and climate change have battered the region: temperatures have already begun rising, drought has caused massive forest fires fanned by the Peninsula’s hot winds, swarms of locusts have descended on milpas, a species of local deer faces extinction, and jaguars fleeing the torched monte have invaded cattle ranches. The catastrophes are reminiscent of another in this area: many scientists believe that 1,100 years ago, deforestation and climate change caused the collapse of the ancient Mayan civilization.

The now permanent droughts leave droves of people in the poorest, driest corners of the country with scarce sustenance and little option but to emigrate. Nearly one million Mexicans a year leave dusty rural homesteads in search of a way to feed themselves, with half ending up in the United States. The other half gravitate toward Mexico’s urban areas, where the infrastructure is already dangerously overtaxed. Mexico City—built atop ancient Tenochtitlan, the Aztec imperial city of canals and floating palaces on Lake Texcoco—is now so parched that many neighborhoods go without running water for days at a time, year-round. The scrubby hills on the city’s edge are covered in a kind of warehouse of human life: dull gray jumbles of unpainted concrete homes stacked haphazardly upon each other, where newly arrived migrants from nearby states flock when fortunes go sour in their own desiccated villages.

Úrsula Oswald Spring, professor at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México and former Minister of Environmental Development for the state of Morelos, studies the tide of environmental disaster which has already begun to hit Mexico—massive deforestation, pollution, salinization and scarcity of water—and the repeated failure of the government to heed the danger. The government pays enough attention to invite her, from time to time, to present to the Congress on the threat of climate change to food security—though she usually causes a stir with her opinions. Yet one of her less publicized views may particularly propel official action: that environmental damage feeds Mexican organized crime—and the resulting violence—with people fleeing to crowded urban areas where they can earn more in an hour, illegally, then they could in months of farming.

Despite specializing in the study of catastrophes, Oswald Spring told me that she believes there is still time for mitigation before the degradation becomes irreversible. Often, she said, the most promising of such programs grow from the bottom up. There is, for example, a non-governmental program run by campesinos which has taught farmers in the state of Oaxaca sustainable agriculture and water conservation techniques for over twenty years. The group—which now receives a minute portion of funding from the government after long relying solely on private donations—has even been successful in a region where desertification has been endemic since Spaniards introduced goats which ate the native vegetation. They build canals in fields to prevent erosion, rooftop rainwater-capture systems, low-energy stoves producing less smoke, and create education campaigns encouraging farmers to organically grow pre-Columbian corn rather than use genetically modified seeds.

But time is running short, and the government shows little interest in stemming this looming catastrophe of drought. “What the government cares about is making lots of money,” one village program leader told me. “What does it matter to them if the campesinos are screwed? They don’t care like one campesino does for another.”

For nearly fifty years, Eduardo and his brother Celso, six years his senior, spent their lives commuting back and forth from Pocoboch to Cancún, in neighboring, wealthier Quintana Roo. The day before we met, I retraced their path from end to beginning, starting on the edge of Cancún’s Zona Hotelera. I watched from the window of an air-conditioned shuttle as the landscape changed from dense, low jungle surrounding the airport to the drab length of highway running towards the hotel zone. Children swam in an inlet off the road, lacking access to the strips of white sand and shimmering, transparent Caribbean flanking the Sheraton and the Ritz-Carlton. In sight of the rows of massive white resorts, uniformed hotel employees sweated as they waited for buses to their homes downtown. Tourists in flip-flops and braids strolled to shopping malls housing Hooters, Starbucks, Burger King, and bars advertising Jell-O shots and Corona specials. As we neared downtown, and my beachless budget hotel, I winced at the shops and hotels adorned with faux-Mayan reliefs—orange-tinted stucco walls mimicking the stone carvings of gods and miracles at Uxmal and Chichén Itzá.

Before 1970, when the Mexican government selected it as the spot for the next Acapulco, Cancún was nothing but a deserted sand spit. When Celso and Eduardo first arrived in the early 1970s, the city did not exist, and neither brother spoke much Spanish, although they had been traveling for a few years to Quintana Roo and Belize working as ranch hands and cutting sugarcane. (Eduardo’s sole pleasant memory of those years is tinged with fear—being smuggled as illegal immigrants into Belize at night by canoe along with other men from Pocoboch, none of whom could swim.) Although the brothers spent grueling days in the sun in Cancún hauling out rock and sand to sell to the companies developing the hotels, the work was a step up from shoveling cattle manure.

In Cancún the brothers were closer to Pocoboch, where they returned every two weeks. Eduardo is quick to dissuade me of any bucolic notions of his pure love of the land, however; having never known a world outside of Pocoboch, he was deeply homesick for his family, language, and the village itself. But not the land. Never the land. Even then he was still a slave to it, helping his father plant and harvest in between treks to Cancún. Later, after he married Ada María and became a father, when he and Celso worked as barmen—the boost that allowed Eduardo to build his house and start construction on a second one—they commuted back and forth. The two nights they worked they slept at their sister’s house in Cancún and tended their land the rest of the week. (Celso has never married, and since becoming disabled after breaking his leg at the hip falling from his hammock three years ago, Ada María and Eduardo have cared for him, along with the brothers’ elderly mother.) Although Eduardo learned traditional Mayan farming techniques from his own father, and it is still common for Pocoboch boys to help in the fields, Eduardo has never even allowed his children to set foot on his plot. Their place is in school, not reliving the work and poverty of his life, he insists—even though this has meant that his son and two eldest daughters have left, his son for Cancún to work in a hotel and the girls to the resort island of Cozumel, working in a hotel and selling cell phones. And that soon Geidy will leave, too.

I had first heard of Pocoboch while passing through Cancún a few months earlier, talking with Erik Bastarrachea, a cab driver with Mayan features, brown hair, and light eyes, who was married to the daughter of one of Eduardo and Celso’s sisters. Perhaps because he left Pocoboch as a child rather than an adult, Erik described his childhood with a sharp mixture of yearning—for walks with his father to their field before dawn when the cornstalks, monte, and air were still coated with fog—and bitterness that he could never afford to go back to farm. In contrast, the rest of Pocoboch’s young want out and generally refuse to return, such as Eduardo’s older children and the cousin Erik sends to drive me to Pocoboch in March, Felipe (who is also the son of Eduardo and Celso’s second cousin).

By ten in the morning, when we loaded into the air-conditioned car with Felipe’s wife (from the town adjacent to Pocoboch like Ada María,) and their young daughter, the day was already steamy. At the periphery of Cancún’s sprawl, we passed clustered shacks of plywood and cardboard. Bands of federales watched the road from the beds of green pickups, machine guns at the ready. (While much of Mexico has exploded recently in paroxysms of drug-fueled bloodshed, Cancún has remained relatively calm, save for the assassination of the city police chief in 2006 and the arrest this spring of the then-current chief—for the torture and murder of a retired general helping the mayor fight organized narco-crime.) For a long stretch past Cancún proper, the road was dusty and dilapidated, edged by piles of rocks and scrubby, mangled jungle vegetation.

On the open road, we traded one vista of desperation for another, as we sped past small, sun-soaked Mayan hamlets. Clothes dried in the sun, strung from rustic palapas; pink-throated turkeys and scruffy white and yellow chicks rambled in traditional Mayan kitchen gardens, amidst spatterings of overripe oranges fallen to the dirt. There were pueblos with names like El Eden, and outposts called Panadería la Bendición de Dios—the Blessing of God Bakery. Lush banana trees, coconut palms, and squat shrubs of papaya held the promise of small bunches of fruit, as long as a hurricane didn’t come along. Simple one-story concrete-block houses were adorned with marigold bushes and incandescent shocks of bougainvillea, in neon pinks and oranges. The dusty plazas were empty, and elderly women in embroidered white cotton huipil dresses waited for buses that never seemed to arrive.

As we moved through the flat landscape of sun and verdant jungle, Felipe and his wife gave me a primer on Pocoboch. All the young people leave for Cancún in hope of saving up money, they told me, until, as the tales sometimes end, their fortune runs out and they are forced back, where there are simply no jobs other than working the land. Although Cancún is just a few hours away, the exiles return rarely, most often for the August village festival, where they drink and trade stories and watch the crowning of the Queen of Pocoboch. No one speaks Maya anymore; although elementary schools are just now starting to teach it, kids want to learn English to get good jobs in the hotels.

The road was nearly empty until out of the jungle a swarm of pale yellow butterflies flew. Then a single crow. Then a small flock of white doves. Near noon, when we saw a boy selling fruit in the scorching sun, Felipe’s wife asked to pull over. The boy, who looked to be about six years old, wore a sun-bleached blue t-shirt and clear plastic sandals. As she opened her wallet to pay the boy fifteen pesos for a bag of soft, pear-like zapotes, he leaned against the unrolled car window with his arms crossed, staring at Felipe’s daughter. She was chubby, cool, and comfortable in the air-conditioned car, and laughed as she watched the Disney cartoon Ratatouille on a tiny DVD player, playing hooky from school for a surprise visit to her grandmother. There was modern Mexico and the rural past it would rather forget, eye to eye.

At kilometer eighty, Felipe turned at a fork in the road, and the scenery quickly became parched. Against the perfectly robin’s-egg-blue sky, what were once thick caps of jungle were now a ragged horizon of leafless branches so dry it was as if a fire had swept through. Thin rows of palm trees hovered over scorched stretches of abandoned land; piles of blue water bottles and refuse lay strewn over other plots. Ahead, four vultures devoured the carcass of a cow. Soon we were nearing Pocoboch, and Felipe pointed to a twenty hectare plantation in the distance where some of the men have gotten jobs picking Maradol papayas for export to the United States. Out of the stifling dryness, the entrance to the pueblo was cinematic: the green of banana trees and carefully tended gardens, dogs roaming the streets, and, when we finally unrolled the windows, the smell of wood fires thick in the heavy afternoon air.

Eduardo wakes every morning at four thirty. Perpetually worried that he will exhaust himself, Ada María rises with him to prepare the only breakfast she can get Eduardo to eat—two small rolls and a bit of coffee—before he bikes five kilometers down the road. Because he now earns nothing from his own land, he works on a second cousin’s land, sowing and harvesting for about forty dollars per week. When I awake after seven at the home of Aurora Romero—Felipe’s mother, sister of Eduardo’s employer, and owner of the general store and tortilla shop—Aurora has already started her three employees preparing the corn for nixtamal. They boil dried kernels over an outdoor wood fire in water and lime to soften them. Then, they take the previous day’s corn, which has soaked in the mixture overnight, and rinse it to grind and press into hot tortillas. Before Mexican corn prices plummeted and local yields failed, villagers sold Aurora their excess; now she buys sacks of Maseca corn imprinted with a 100% MEXICANO label which villagers complain has no flavor. Ada María no longer boils and grinds her own nixtamal by hand with a stone metate, and instead buys tortillas from Aurora, as do most women in Pocoboch. With just Geidy left at home, there is less incentive to hand-press tortillas more than once a week: like many Mexican teenagers eager for the white bread and potato chips on television, Geidy barely eats even homemade tortillas.

Aurora watches, as well, as the rest of Pocoboch’s history slowly vanishes. She tells the story of the Hacienda San Roman and the Mayans kept as slaves there, including her father-in-law’s parents. Before fleeing during the 1910-1920 Mexican Revolution, she and the rest of the villagers claim, the owners treated the slaves very well. As she talks from behind her store counter, seventy-nine-year-old customer Enrique Canul Canche adds details in Maya that Aurora translates. Around the time the hacienda owners left, they say, Pocoboch was invaded by indios from another village—like Indians in the movies: men with swords and women with bare breasts. (A crowd of children gathers, giggling at the thought of the savage indios and shooting each other with imaginary guns.) In the invasion, only the villagers who escaped to the monte survived; those who sought refuge in the church were burned alive when the invaders lined the roof with sacks of chiles that they set ablaze.

The Mexican Revolution may have set the process of land reform in motion, but it was not until over a decade later that landless peasants actually gained land. Until 1911, Mexico stagnated in the thirty-one-year Porfiriato, the rule by continued crooked reelection of President Porfirio Díaz. While Díaz did much to industrialize Mexico, he also courted foreign investors with generous subsidies, encouraged private landholders to buy up public land at fire-sale prices, and allowed landowners to appropriate the communal land of indigenous groups. Just a few years into his reign, a few wealthy owners controlled the majority of Mexico’s arable land, and industrial agriculture for export condemned impoverished rural Mexicans to another kind of slavery. In 1934, private land was redistributed to campesinos as cooperative lands called ejidos, the concept of which had been common in indigenous Mexico centuries before. While ejidos enabled campesinos to work for themselves, the arrangement had drawbacks: the land couldn’t be sold, and although much of Mexican soil had already become dry and degraded, many ejidos lacked water for irrigation, a privilege reserved for export factory farms in the arid north. By the time Eduardo was born, his parents and countless Mexican campesinos were mired in a dilemma: they had land—which, fortunately in Pocoboch, was still richly productive—yet no water, agricultural resources, nor a market to which to sell their crops.

I am still in Aurora’s store near noon when Eduardo returns early from work, dressed in khakis covered in a fine layer of red dirt, disintegrating brown leather shoes, and a faded blue baseball cap. He wants to show me his milpa. We walk in the opposite direction of the highway a few blocks, past large concrete-block houses of villagers who have done well in Cancún and simple wood palapas of those who have not been so lucky. We then turn onto a dirt path into the jungle. What was once verdant and lush is now a spindly mass of skeletal brown and gray limbs, the only leaves still remaining faded to a sickly matte yellow. The landscape could be mistaken for a New England forest in late fall, apart from the blasting noon heat and the grainy red soil crunching under our steps as we enter Eduardo’s corn patch. “The land will not withstand any more,” he says. “It does not give. If I buy fertilizers, I am just throwing away money, and there isn’t money, either.” Stretching towards the monte are rows of spent gray stalks, which shatter sharply as he bends them in half to keep the birds away. Hidden inside the heat-curled shells are what would have been the ears, shriveled and unformed, some smaller than my thumb. He once harvested a ton and a half of corn each year—1500 kilos—but last year eked out five kilos, less than forty cobs.

As he points out shriveled watermelon and beanstalks, Eduardo listens for the doves and urracas which used to sing to him in between eating fruit in the monte. From time to time we hear the voices of farmers, but far fewer than in the boom 1980s, when villagers could actually prosper selling their corn and Eduardo and Celso made good money tending bar on the weekends. At that point, the government had been helping campesinos for a few years, giving away fertilizer and herbicides and facilitating corn sales at regional distribution centers. Through the ejido structure, the villagers rotated planting to let spent plots rest for a few seasons, and the damage the chemicals were wreaking at first went unnoticed. Then, in 1988, Hurricane Gilberto hit. Tourism collapsed and the Cancún bar where the brothers worked closed; Eduardo’s half-constructed new house was demolished, and Ada María fell ill with pneumonia.

By 1994, when the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) passed, the brothers had not recovered financially. Neither Eduardo nor Celso had an inkling that, with NAFTA, the government would slash prices for American imports of corn and food staples, leaving Mexican farmers unable to compete. But they had noticed that the government had been quietly winding down its farm aid. Eduardo says: “The distribution center closed, and the tortilla shops stopped buying corn from campesinos. So the pueblo ended up locked in—we produced corn, but there was nowhere to sell it.” Like small towns nationwide, Pocoboch quickly began hemorrhaging residents. Eduardo’s remaining siblings left for a new pueblo in southern Quintana Roo established by Pocoboch exiles, and he and Ada María sent their eldest child, Luís Eduardo, to work and live with Eduardo’s sister in Cancún because they could not afford to send him to school.

At the end of the 1990s, after the government had begun allowing ejido members to sell land, the Pocoboch ejido privatized. (Agronomists in the state capital say that the government pressured ejidos in valuable areas to privatize and sell, often for next to nothing.) Villagers now have only one small plot—not enough to rotate planting to keep soil healthy—and, as temperatures have risen and rains slowed in the past fifteen years, what they are able to squeeze from the land has slowly diminished. The dryness, Eduardo says, is more vicious than the increasingly frequent hurricanes: instead of losing one year’s crop and being able to depend on a stockpile, campesinos must now watch their livelihoods die, little by little, each day. As he shows where he has cut dead growth to prepare for planting, he tells me that his children have already begun sending money to help. He is constantly filled with dread: about the price of food, the financial crisis worsening, his family’s health. This year, if the land does not produce, he will likely give up. “Es lo único que sabemos hacer,” he says. (It is the only work we know how to do.)

On the walk back to his house, Eduardo shows me a ranch once owned by a man named González. “Then his children got married,” he says. “They left. And the parents died. And here in the pueblo, there is not a single member of their family remaining. We are under the same risk, because our children are able to go to high school and they leave to find work, and we are left behind. Some day they will come back, and say, ‘Here in this pueblo lived my parents. Here we grew up.’ It is natural that this will happen. The day that we finally die, our family disappears. There will only be memories left.”

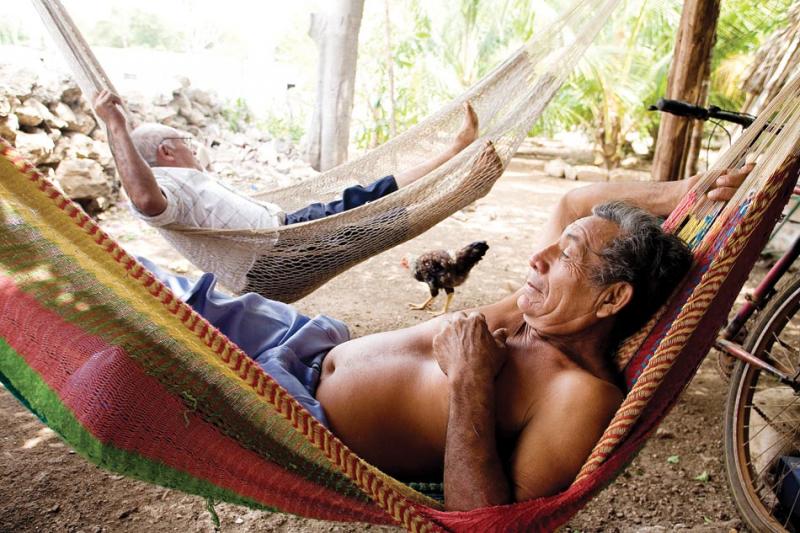

When we return from the tour of his land, Eduardo sinks into one of three hammocks strung next to the outdoor kitchen structure he built for his wife. There, Ada María bends down to light a pile of kindling. She knows that the wood smoke is not good for her lungs, but it is tradition and, more important, firewood from the monte is free while a tank of cooking gas costs hundreds of pesos. Sitting on a tiny stool, she reheats a soupy stew of ibes, the slightly bitter white beans the villagers have eaten for many generations, and then sets a pan with oil over the fire. When the oil sizzles, she throws in a handful of finely chopped purple onions and a bowlful of beaten eggs, the yolks a vibrant yellow. Her daughters refuse to eat these huevos del país (country eggs, as Yucatecans called them), which Ada María collects from her own corn-and-herb-fed chickens. When Geidy returns from school after we’ve finished lunch, Ada María tells her there are store-bought eggs waiting for her. And that I enjoyed my ibes, which Geidy also does not eat. Geidy turns to me and laughs. “Really? Take a kilo with you then.”

As Geidy eats, Ada María and I sit in hammocks alongside Eduardo, who dozes between Ada María’s jokes as she tries to teach me Maya. Across the street, beyond the layers of bougainvillea covering the house, the crumbling church gleams white in the sun and a group of shirtless farmers gathered on the park benches breaks into laughter. Geidy comes looking for me, reminding me that she has promised to show me the video of her crowning as Queen of Pocoboch. In the living room, she turns on a custom-produced DVD of the procession at the August festival. She is taller than both her parents—with shoulder-length black hair and wide doe eyes carefully traced in dark, thick liner—and sweats gracefully in her lacy, embroidered traditional Mayan terno as a succession of partners twirl her to Yucatecan folk dances. When the video ends, she pops in a DVD of her older sister being kissed by a dolphin at a show in Cozumel, and calls out to her mother: “For my birthday present, that’s all I want! I don’t want a cell phone anymore. Look! Look how the dolphin turns!”

Later, when Geidy has gone out with friends, Ada María tells me about their fifth child, a daughter she named Maya de la Cruz who arrived breech and stillborn, and whose remains the cemetery moved a few years back without her permission. Miscarriages were common in her family, and she can’t help but wonder if it was because of their poor nutrition. When Geidy was small, she goes on to tell me, just after the passage of NAFTA, Ada María hid the family photo albums so that Geidy wouldn’t know that her sisters and brother had had birthday parties. And until Geidy was in junior high and complaining that she didn’t like school, Ada María and Eduardo did not talk about their childhoods—about working rather than learning to read and eating only corn mush after their eight hours in the fields. Geidy may be difficult at times, Ada María continues, but she is turning out well: she is respectful, gets good grades, and thankfully hasn’t gotten pregnant, like so many other girls. When Geidy returns in the evening, she sits around the table with Celso and Ada María for one of her daily chores: filling tiny plastic sacks with popcorn and pumpkin seeds to sell to the village kids for a peso and a half, which will net the family a couple of dollars for the night.

The next afternoon, Geidy invites me for a bike ride to see the massive cenote, one of the underground river sinkholes dotting the Yucatán, on a rich man’s land that was once an old hacienda outside town. Although it is still light out, and Geidy’s friend Chucho is joining us so that we will not be two women alone, Eduardo is nervous. We promise to return quickly, and, after convincing the rifle-wearing gatekeeper to let us sneak in, take as quick a tour as possible, given Geidy’s enthusiasm in showing off all the marvels of this most exciting of sites in her town. On the ride back, as the sun fades, the three of us race uphill through the dry monte on tires half-filled with air, all a bit relieved when we reach the main road for the final stretch back. Just after turning onto the road, we see Eduardo pedaling towards us, on a bicycle hastily borrowed just for the trip.

In the morning, Celso shows me his little parcel of land. Celso is stockier than his wiry younger brother, although his bones show through his chest, with balding white hair, a ruddy face, and tired hazel eyes streaked with red. He pushes along a bicycle to support himself as a sort of cane. (Since he cannot work much now, eventually he will sell his parcel to pay his nieces and nephews the hundreds of dollars they loaned him for his leg operation; his siblings and their children paid half the cost.) At the edge of town is a yellow water tower, on land their father donated for a well—although there isn’t enough water for farmers to irrigate and everyone must buy jugs of purified drinking water. Limping, a machete nearly half his height hanging from a rough cord looped around his waist, Celso leads me behind the tower to his plot.

As a crow caws from the leafless trees, Celso shows me the onions and beans in his vegetable patch which have survived with a bit of water, and the jicamas the groundhogs have devoured. (As the monte thins, what jungle fauna remains has become ravenous.) No scientist or expert has ever come to Pocoboch, Eduardo and Celso tell me, and at first they did not believe the news about global warming. “We thought, how are they going to guess whether this will happen?” Eduardo says. “But time passes, and we are seeing in reality what the scientists said.”

In the distance, the whirring of the water pump kicks in. Celso is quiet for a bit, then points a stout, weathered hand to the sky. “For instance, that airplane flying there. In the time when we were children, it rained a lot. But we never saw an airplane. Little by little, there were more airplanes, more airplanes, until now all the time, space is crossed with airplanes. That is what I think poisons the atmosphere—because of the speed of the airplanes flying. That is why, when the rain rises up, it does not fall.” He points up again, now at a low layer of full white clouds. “In the old times, when you saw clouds like that, in just a little bit the rains would come.”

On a particularly hot, sun-parched day, Pocoboch prepares for the arrival of the one government program that actually has an impact on the lives of the villagers. Every two months, the federal program Oportunidades distributes cash to poor mothers whose children stay in school (and elderly people without family), the idea being that women are less likely than men to drink away the money. Early on the morning the program officials will arrive, the town square turns into a small market, and vendors set up tented outposts to sell cheap polyester children’s clothes, shoes, deodorant, toys, and ice cream. Ada María and Eduardo earn a bit of extra cash renting out their front porch to a produce vendor. The Oportunidades officials, however, are irate at the display.

“For the next dispersement, if there are vendors near the program stand, the payments will be suspended until the vendors are gone,” says a young Oportunidades official in a khaki vest imprinted with the program logo. Gathered listening are nearly all of the women in the pueblo, many of the older señoras in brightly embroidered Mayan huipiles and woven rebozo shawls. Until the official began speaking, the crowd of women chatting had the air of a family birthday party. A second official gives a rehearsed primary-teacher lecture about the importance of equality of women, saying how much President Felipe Calderón values their efforts to run their households and raise their children, how much President Calderón would like them to conserve energy and start savings plans for their families, and warning them not to believe any politician in the upcoming congressional elections who says they will cut people from the Oportunidades roll if they don’t vote as they are told.

“This is a resource that comes from every Mexican,” he continues, the ice-cream bells ringing faster and faster, “a resource from those who pay taxes. You have to use it for what it was created. That is: food for your families, school uniforms, shoes for your kids in school. Okay? Make good use of it. You know how you got into the program: you came to sign up, you were given a socio-economic survey, and it was determined that you live in conditions of extreme poverty.” This is a phrase that he repeats at least three times in less than ten minutes, and then is blasted on a loudspeaker over the plaza afterwards, in Spanish and Maya: extreme poverty. When I ask Ada María later if she finds this condescending, the idea that the government needs to remind her not only that she is living in extreme poverty but that she shouldn’t misspend the money it is giving her, she says no: “Imagine if they didn’t give you that little bit of help.” That money, Eduardo adds, is what made it possible to pay for Geidy to finish high school.

After spending nearly an hour in line behind many neighbors not literate enough to sign their payment forms with anything more than an X, Ada María gets her payment of almost forty-five dollars and heads home across the square. There is enough for a small allowance for Celso, who goes to the market to carefully select a new pair of flip-flops, an essential purchase since his foot started to swell recently and is making his injured leg more painful. Neither Eduardo nor Ada María buy anything. Eduardo hands Geidy fifty pesos, and she wanders through the market, cooing over this and that before plucking out two bras and a pair of turquoise flip-flops. I think of the conversation she and I had the night before, sitting on the plaza, when she confided with resignation how much she wants to go to college to study psychology and return to work in Pocoboch. But it is simply too expensive and there are no student loans.

“I would like for my children to have a profession,” Eduardo told me the day we met, although he knows that working in a hotel or selling cell phones is already infinitely easier than his own work. “I am powerless to help them. I am seeing that they want more, but I cannot give it to them. Sometimes when I’m working, when I’m lying down resting, I start to think about that, and I feel sad for them. Because they want to continue. It is the destiny of being poor—if we were to look for a defect, we can start at the beginning of my life. From the beginning of my life, that’s where it started.”

My last afternoon in Pocoboch, Eduardo, Ada María, and I wait for Geidy to arrive from school. The small white van that transports the kids to the high school in the next town pulls up at the village square, and she quickly changes into jeans embroidered with pink and red flowers, a sleeveless pink polo shirt with a red collar, and her new flip-flops. Her parents are in clothes I have seen multiple times over my visit: Eduardo, a short-sleeved pale blue button-up shirt with holes in the shoulder, Ada María, a black blouse-and-skirt combination with pink roses that, in many washings, has become muted in color.

We head towards the milpa, Geidy and Ada María on foot, Eduardo on his bike to run an errand before meeting us down the road. When it comes time to turn off the street onto the dirt path, Geidy has no idea which direction we are headed, and follows her mother like a young child. The horizon is filled with strings of cottony cumulous clouds, and around us whips a strong, dry wind like the California Santa Anas. Geidy is uncharacteristically quiet, chatting a bit with her mother but more often gazing around at the monte in serious concentration. Halfway, Eduardo catches up with us, and Geidy takes the bike to ride in front alone.

She has gotten far ahead by the time we reach the narrow entrance to her father’s land. “Por acá, Geidy,” he calls out. As we enter the milpa, Eduardo talks about missing the food of Pocoboch when he worked in Cancún, and the ability to go to his land and pull up a jicama if he had the hankering. “This is where we get the ibes,” he tells Geidy, motioning to the small white beans. With a calloused hand, he pulls a thin gray-green vine up a bit from where it has attached itself, in a delicate spiral, to a parched brown cornstalk. Geidy stares around, taking in the shriveled dryness of this place where her father has worked harder than a man should to grow the food she has eaten her whole life. “So many ibes,” she says, not quite under her breath.

What does being here make her think of her father’s life, I ask after her parents have wandered away to study the crops. She is at first coy, pretending to not have an opinion, but when I press, her answer comes fast. “Why does he do it? Why does he farm?” she asks aloud. Her harsh thoughts sound troubled rather than malicious. “Why didn’t he go to school? Why doesn’t he know how to read?” It is a question, she says, of her modern thinking versus theirs—the antigüita. “I don’t know. I think it was the ignorance of before, the lack of being able to study. Maybe he could’ve done something more to get ahead. Looked for more opportunities somewhere else. But they got accustomed, and they’ve stayed.”

The gravity of her words hangs over us, and Geidy is silent. After a bit, we drift back to her parents; I take photos of the three of them squinting in the sun, and Ada María jokes as always, borrowing my sunglasses for a glamour shot. Soon we begin the walk back, the dry leaves crackling under our feet, Eduardo pushing the bike back up the small hills. Ada María and Geidy walk ahead, and when I ask Eduardo how he feels bringing Geidy to his land, he instead tells me what he imagines is in his daughter’s head. “She might feel sad because she sees where I am struggling, where I am earning a bit so that she can go to school. She should think of that when she sees the place where I do this brutal work. The children should think about how they are seeing how we suffer, how we work so that they can study. The first thing that they should think is, ‘What is happening to my dad isn’t going to happen to me. I am going to study.’ That is what they should think.” He is content to have shown her the place from which he has always fed her, he tells me finally. But not proud.

When we return to Pocoboch, a taxi waits to drive me the half hour to the bus station in the closest city. Ada María and Eduardo insist on joining me for the ride, and we take a detour to the neighboring town to drop Geidy off. Because the end of the term is near, teachers are rushing to cram as much in as possible before the students graduate—and, most likely, head off to work in Cancún—so her class has been called back for special evening classes, and Geidy wanders slowly towards the school as we drive away. Out on the highway, the dry wind from the monte is overpowering, the sun still searing. Just before entering the city, we pass a crossroads where workers are building a bridge over the interstate highway. We watch as a group of young, dark-skinned men in hardhats scramble amidst the piles of dusty white rock. They break the rocks into pieces with jackhammers, Ada María lamenting how hard their work must be

Research for this article was supported in part by the Middlebury Environmental Reporting Fellowship.