1.

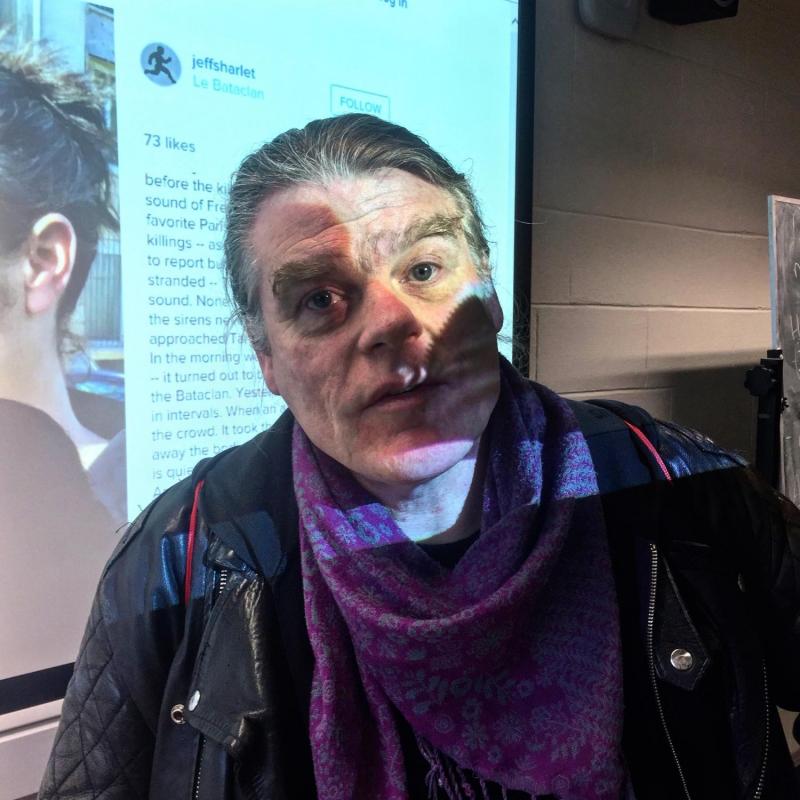

“They say the Bataclan was the first attack on music,” says Bart, “but ’twas not. ’Twas the Miami Showband.” Bart’s come to help me set up a projector at Trinity College, where I’m to talk today about Instagram. We project one of my own, a video of a photographer in Paris, taking a picture of a dog pissing on the sidewalk, across the street from the Bataclan Theatre, the Sunday after the attacks.

“I’ll want sound, too,” I tell Bart. “Give it a go,” he says. There they are: day-after sirens, not urgent—the dead being already dead—just steady. Bart listens, and thinks of the Miami Showband.

Matching suits, synchronized dance moves. “Quite unpretentious,” he says. “They played the pop tunes of the day.” July 31, 1975. Ulstermen in British Army uniforms stopped the band’s van, ordered them off, and planted a bomb. “The attempt being,” says Bart, “they would later associate all Irish as being terrorists.” Maybe they planned to “discover” the bomb, undetonated: evidence. Maybe they meant to pack the group back in the van and blow it up down the road: Irish mad dogs, exploding themselves. But the bomb went off too soon, killing two Ulstermen who were setting it. The musicians were witnesses. “So,” says Bart, “they basically murdered everybody in the band.” A trumpeter took four bullets, a guitarist seven, and they shot the singer 20 times. The sax player blew into a ditch; bass was shot but played dead and survived.

The sirens sound throughout Bart’s story. Instagram’s like that. It loops. Loop after loop after loop, and it’s never the first time, it never was. Later, a friend asks me about Paris and I tell him about Miami, and he says, yes, he knows, and he sends me a poem in the band’s memory, by an Irish poet, Paul Durcan. It ends, “You made music, and that was all: You were realists / And beautiful were your feet.”

The beautiful feet are from Romans, which borrows them from Isaiah, which no doubt took the phrase from something older, somewhere back in the before that loops round to the after. A cover song. Like Miami’s “There Won’t Be Anymore.” Like “There Goes My Everything.”

2.

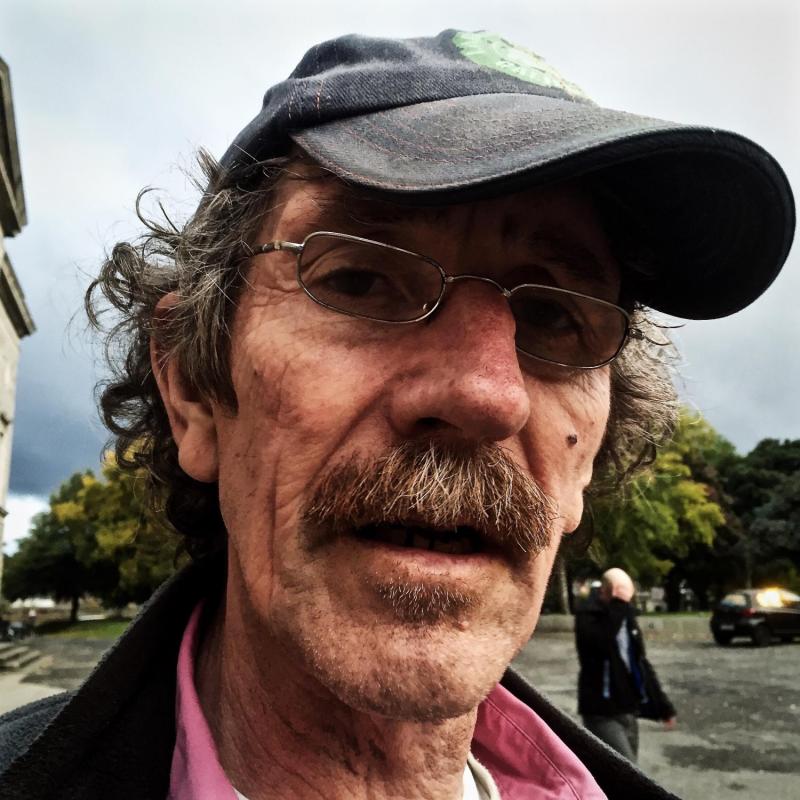

He’s not a racist, says Aidan, he’s a plasterer. He builds walls. Built. He built walls. Currently he’s in between. Between what? I ask, meaning the job no longer his and the one he may yet have. A pint and a stroll, he says. He was on TV once. Man-on-the-street kind of thing, about the Syrians. “Taken our share,” he’d said. He’d like to help them, he says, but—not a racist, you know, but those Syrians don’t need our help. Not them that are here. They are rich men, their money hidden, and they only hire their own, and their own do terrible work, they cannot build a right wall, and they pay wages no Irishman could accept. And besides, they won’t give an Irishman a job.

Aidan prefers the pub to politics, there’s a favorite of his right back there. Four or five blocks. Yes, I say, I saw you outside. “Yes, you might have,” he agrees. I wondered how he’d come on me here, a few yards back, beneath a stone arch, reading school children’s graffiti: “Miss Law”—the rest of her name obscured by a slash of green—“has the best ass in are school.” A conversation-starter, that one. We trade our places: Vermont, where I’m from; he’d been to Montana once to see a sister. Drives a red car, he says, an Irishwoman, perhaps I knew her?

I let that one sit. “I’m just fecking with ya,” he says. Let that one sit, too. “Been to Chicago,” he offers. And he does have a sister in Montana, or did; and a brother in Chicago, or did; and more brothers and sisters back home in Sligo, or did. I lose track of the maladies. Dead, dead, dead. That’s the main fact, and Aidan’s last man standing. If you don’t count the brother on his back with leukemia.

Clouds coming up, black and silver, but the sun’s last northerly light fills the window of a parked car with gold. I squint. Aidan coughs. We stroll. “Who’s your favorite singer?” he asks. He wants to tell me his: Neil Diamond. Neil’s best is “September Morn,” thinks Aidan. “But I don’t know where he’s from,” he says. “New York,” I tell him. “Brooklyn. A Brooklyn Jew.” “A Jew!” says Aidan. “Oh, that one can sing. I cannot, I cannot sing. I am a plasterer.”

3.

I’m being chased by a man on a bicycle. I know he’s coming for me because he’s shouting. “Hey, you! You!” I’m the only one in this stretch of park, walking fast, but he’s on a bicycle. Standing on his pedals. Tight Dublin-blue hoodie and paint-speckled jeans. “Stop!” he shouts. I stop. He stops. Straddles his bike. “You taking pictures of my house?” he says. Oh! “I was,” I say. “You were taking pictures of my house!” I hold up my phone. “I’m a photographer,” I say. Half a lie. “You told my mum you fancy our telly,” he says. Oh. Yeah. I did.

The woman who must be his mother, with a boy who might be his son, had arrived at their stoop just as I took this picture. “You fancy our telly?” she’d asked. “Yeah,” I’d said, “I mean no, I just liked the way it glows through the window.” “Right,” she’d said. I’d said, “I’m sorry.” She’d waved it away like something silly. Or so I’d thought.

I show her son the picture. He stares. “What’s that about?” “I don’t know,” I admit. “I’m a journalist. I walk around—” He holds up a hand. He gets it. “Okay,” he says. “You can’t be too careful. Lotta Romanians around.” He means Roma. Gypsies. He starts telling me about them. How they pretend to be beggars even as they live in mansions. How they pretend to be Muslims to grift alms from those good people when they go to their Muslim churches on Friday. How they are neither Muslim nor Christian, they are a religion of their own selves, and how they believe their ancestors stole a nail from the Romans and so there was only one for the both of Christ’s feet on his cross and for this mercy God gave them a dispensation to thieve. Oh, they are thieves, insists the son. “Drop the eye out of your head!”

“I can delete the picture,” I offer. “Naw,” he says. “I don’t think you’re a Romanian!” He laughs. “Not much of a picture, though, is it?” It’s not. But the television—the one perhaps he’d been watching when his mother walked in the door with her tale of a Romanian who as much confessed he’d be coming back for their telly, and would you please go right now and give that fella a talking to and whatever else may need be—it glows.

4.

“Rebecca” thinks you’ll think she’s bad because she works in a massage parlor, so she doesn’t want to show her face. She scrolls through her phone, snapshots of her city, Kuala Lumpur, her mother, her brother, her sister, her nieces. She takes out her passport to prove her age. I show her mine. “May baby!” she says. She’s May 12, I’m May 7. She’s 48, I’m 43. “You fat,” she says. “And I ugly.” She’s “ugly” in the terms of her trade because she’s 48, and because she’s ugly she has to massage fat men. “Big men!” she says. It’s unfair. They pay the same price as the small ones. But there’s so much more territory. She squeezes her right shoulder. Nobody ever asks if she wants a massage.

I offer to pay for her time, my notebook on the table instead of my body. “No need,” she says. I say, “It’s only fair,” but she shakes her head. “No. Need. You respect me, okay?”

“Rebecca” says she’s the oldest single woman in her family; had a boyfriend once, a long time ago; worked most of her life as an accountant; quit at 45 to study massage; learned about “extras” on her first job; left Kuala Lampur three months ago; came to Ireland “because, because, because…” She doesn’t know. She studies English 9 a.m.–1, works in the parlor 1 p.m.–9, walks home, cooks—“good cook, yeah!”—sleeps, repeats.

“I choose,” she says. She’s speaking of the extras. “I do not have to.” Men ask, yes, they always ask. Kelly, her boss, doesn’t ask. That’s how it works: Kelly doesn’t ask, doesn’t know. Deniability. “Client is boss,” Rebecca says. “I am service.”

There’s more, but we can’t get to it. “Truth,” she says, looking for the English to describe how much she can say. I draw a circle, divide it, point to the lesser half. Yes, she says. That much. She pushes my notebook across the table and takes my phone, holds it away from her face, considers it with a sideway glance, takes three selfies. “Here,” Siow says. These are for me. “Respect,” she says. This—“Rebecca,” the jungle wallpaper, her gold band, the pale pink of the polish on her nails—is for you.

5.

He’s smoking heroin from foil, hers is meth on top of a smoke-filled Coke bottle. Michael’s 38, Siobhan’s 20. He likes me, she does not. He’d like to chat, but Siobhan would like 100 euro. Twenty? Twenty, agreed. “Who holds the money?” I ask. He takes the bill, hands it to her. “Married yet, are ya?” she asks me. I show her my gold ring. “You?” I ask. “No,” she says. She pulls her bruised face away with gently bleeding nails, a little bit of red paint still on them.

“She’s my sister,” says Michael. A Dub voice so low and soft I lean in close to hear and feel his breath warm my cheek. “I’m her brother,” he says. I say, “It usually works like that, doesn’t it?” He smiles. He likes me, she does not.

Long time sleeping rough, he says. He picks at a black-ridged sore on a swollen hand. They both wear shelter shoes, but shelters are not right for a sister. “Bad crop,” he says of those you’d find there. I look at the half-eaten chocolate bar beside him. A liter of chocolate milk. A newspaper he squints at when the drugs are in his sister’s hands. Their legs stretched out. Their matching black toques, not so much pulled down on their heads as perched atop, like sleeping caps in a children’s story.

Michael’s eldest. “She’s the baby. I look after her.” They say there are six between them, brothers and sisters. Possibly seven. He takes off his hat, asks me to take a picture so he can see the state of things. “D’ye ever bleed like that?” he asks. I roll up a pants leg, show him my well-scabbed shin. “Psoriasis,” I say. He nods. “Likely that’s it,” he says of the sores on his skull.

Siobhan sets to work on her own head, digging with both hands. She asks if she can borrow my phone. “To get us a place,” she says. She gets her man: 20 euro, she tells him. That’s what she has. He says he’ll be around soon. Michael wants to stand. But that right foot, it bends like there’s no bone. “Wait,” says his little sister, half his size and holding down his knee. Then, to me, “Can you leave us alone together now?” Michael says, “Don’t make us look bad.” I would never. “Our mother and dad may see this.” I nod. He looks down and flicks his lighter. The foil scoops up the flame’s little yellow glow and turns his face, his scabs, golden. “Just say us as we are.”

This essay is part of our #VQRTrueStory project, a social-media experiment in nonfiction that delivers stories across platforms. Each week, a contributor takes over our Instagram feed, @vqreview, to post original dispatches that tell the stories behind the pictures. The dispatches are then published on our website, and two are selected for inclusion in each issue of the magazine. You can visit the #VQRTrueStory archive to read all the contributions so far. And be sure to follow @vqreview to keep up with the project as it unfolds.