Windhoek, Namibia

“Okay ladies, let me see you walk like a cow!” Utji Muinjangue cried.

A dumb look passed between artist Simone Leigh and me as we stepped onto the runway of the tiled corridor leading from the back of the house. Long-horned headpieces, fashioned from teal and turquoise animal print, and a sherbet pink and blue mélange of chiffon, that matched our dresses, balanced on the front lobe of our heads so that the rhinestone brooches at their center blinked like a third eye. I felt mine slip under my soft Afro.

“Don’t worry! It will never fall!” Mushe, one of the women who had dressed us, encouraged. “Walk!”

I made cautious steps, maneuvering three layers of white lace petticoats and a bright-colored underskirt beneath the wide hem of a dress that fell at the toe of borrowed heels.

“Like a cow …”

“I don’t know, I just feel like this needs a little more—it needs to be fuller. And sit up a bit more on my head,” Simone mused. “I’m not feeling it.”

We were wearing traditional dresses of Herero women, an ethnic group found mainly in Namibia and Angola.

Simone had gained a critical following in the US during a high-profile residency at the Studio Museum in Harlem and a show at The Kitchen partly for her series of women’s ceramic heads, the earliest ones inspired by Herero aesthetics. Her sculptures were often crowned with askew headpieces, reminiscent of Afro puffs or coiled dreadlocks, blooming with a large accretion of tiny porcelain roses. The faces seemed to turn or lift subtly in a way that revealed searching, with an air of what almost seemed a disturbance.

I laughed at Simone’s jest, knowing I inhabited the imagination of those installation heads. We wore pillbox-like hats fashioned from a few yards of cloth and straight pins, wound over rolls of newspaper sculpted into neat, narrow horns. About the Herero headgear that I was wearing, I felt inspired but, like Simone, also unsure.

As we stepped into the living room, the small crowd there clapped approval.

“A cow, Utji?” I asked.

“It’s all about the cow!” our host declared. Circle formation in the air.

“Ahhhhhh, you look like Herero women! Beautiful!” was the echo.

They admired our girth, the way the dress closed off the cleavage but set off the bundle of the breasts, substantiated the fullness at the empire-drawn waist, marked by the line of a thin cinch belt and a puffed-up shoulder that tapered to a skintight length of sleeve. The borrowed costume jewelry and the layers of a wide shawl added to our largess.

“You move like this!” Utji instructed. She slowly crossed the living room, feet close together, her weight shifting heavily, but sensually, from one rump side to the next, her head ever so slightly moving as a reverb.

Left, right. The insouciance and bored majesty of the cow.

We were instructed to sit on the terrazzo floor as Utji arranged the layers of petticoat, the wide, heavy circle of our skirts. We wore only three of up to eight layers of petticoat. While Thabiso Sekgala, the South African photographer who was Simone’s collaborator, maneuvered his Hasselblad, we sat under the admiring gaze of Utji and her friends, including Utji’s children and some from the neighborhood. They were all dressed in the latest jeans imports and modish tracksuits, sporting ubiquitous gold jewelry, hair weaves, and the latest braid styles, up-to-the-minute sneaker styles, cell phones setting off alternately with kwaito music ringtones and electronic cries of “Utji! Utji! Utji!” and “Teleeeephoooone! Teleeeephooooone!”

I had caught up with Simone in the capital of Windhoek before she embarked on research for new sculptural work. Our shared interest in southern African social history had led us to Utji’s house, where a mutual friend, a returnee after three decades of exile in America, promised that we would get a political history lesson over tea. Talk of dresses turned easily to apartheid and genocide; Simone and I were fascinated by modern Herero styles, which articulate much about the nation’s tragic colonial history.

This fascination made me suddenly conscious of us as twenty-first-century “black-eyed squints”—to play on the Ghanaian writer Ama Ata Aidoo’s notion from her celebrated 1977 novel Our Sister Killjoy—two women of African descent (Jamaica–Chicago–Black Boston), moving south from west, looking forward and backward through the lens of our own Africa.

Utji and her friends had slipped easily out of what might have been a centuries-old parody. We were dressed for them: Gone Herero. Except we looked like costume characters on an antebellum-to-Afro-futurist fantasy set.

After our walk in the dresses, Simone and I tried to explain to them how foreign it was. Not their company. Not the intimacy we’d quickly found sitting for hours at Utji’s table talking, the intimacy that continued into her bedroom where she opened her wardrobe and she and three friends pinned and tied and pulled with their teeth the thread and laces of the dresses, tightened our belts, and instructed us to push our breasts up into the bodice.

Not Namibia. It was not foreign.

Not the dress itself—like many contemporary African dress forms, it retained the bones of Victorian design, introduced by German, Finnish, and English missionaries who arrived in the nineteenth century.

It was simply this reverence of the cow.

“In the US, calling a black woman a cow is a deep insult,” we feebly explained. “‘Whole heifer,’ it is one of the worst insults.”

They looked at us amused, but it was clear they were not really taking it in. Ours is a post-Mammy, post-chattel story that is as foreign as their heifer pride.

For Herero and Himba peoples, the cow is everything. Much more than we then knew.

Over local beer and snacks, we had talked for a good part of the afternoon, Simone and I mostly listening as the conversation moved in and out of English, Herero, and Nama, against the backdrop of the young girls’ play and Olympic sportscasts from the living room. An intimacy grew from the symmetry of our full bodies, middle-aged or nearly so—the kind of easy sensuality that emerges with age and child-rearing, the return of several of us to school to ward off the impoverishment of divorce and single motherhood. Simone and I reflected on the struggles of keeping families afloat as we advanced artist careers in New York City, as our new friends’ talk wandered from the urban universities where they were lecturers and graduate students to the rural farmland where they kept cattle and smaller livestock, inherited at birth, exchanged as bride wealth, or purchased with professional salaries. They regarded this capital, this tradition-keeping, with enormous pride; but a visceral sense of regret, a resignation, a tinge of embarrassment shadowed their words. As much as they were keepers of tradition, their lives had become caught up in the cosmopolitan trappings and differing measures of the world of urban Windhoek and beyond.

Theirs were different from our own considerable fractures and preoccupations—as different as the aesthetic of Afro-puffs versus horns. The substance of what could not be easily spoken of, and what was shared, however, was there in the material and the metaphor of the dress.

Feeling awkward and matronly, I had asked Mushe, a woman in her late twenties who was dressed in heels, tight-fitting jeans, and a silky blouse, how she felt when she puts on the dress.

“Ooooooh, I feel like a real woman!” she said passionately, as she struggled for the right words.

There was a palpable reverence for the dresses among them, not unlike American fetishizing of the bridal dress. Then, it was not so different from the relationship many urban African women have to clothing. Western dress is beloved; it is the trying on and wearing of a certain power, a certain relationship to one’s sexuality, one’s body, that is born out of wearing jeans, T-shirts, Lycra dresses, up-to-the-minute ready-made styles. Yet I don’t know so many African women who consider themselves truly dressed until they wear “traditional” clothing, however innovative or hybrid the form. Western dress lacks the sculptural aspects created with every pull of thread. And it often lacks sensuality, when the body is so out front. In Herero dress, as with the Ghanaian kaba and slit and other contemporary West African dress, there is an emphasis on construction; the sensuality is powerfully present below. Simone likened our borrowed dresses to a Viktor and Rolf design. But unlike the kaba and slit and other dress rooted in the Edwardian and Victorian periods, with added colonial missionary discomforts, the body was muted by the covering. Even at their most modest, these other dresses become sensual, form-fitting. Girth matters. Rump matters. It is all about the S-curve. Here, the curve is sublimated. The dress seems oddly disproportionate to the body inside. And so I was that much more surprised by the younger women’s embrace of it.

I asked Utji and the others why this form of dress has had such a powerful appeal, and for so many generations. Why had it not receded in fashion, given its staidness and association with colonialism and the violence of Christian missionaries? I knew the answer was rooted in the German Herero War of 1904 and the legacy of genocide. These horrendous events animated Herero dress forms in a way that few non-Namibians—attracted keenly to the visceral old world, costume-y, and sometimes even fantastical elements—recognize. If our friends had not explained in detail about this history, the truth would have been lost on me, or I might have understood the admiration for these dresses as a blind spot of consciousness, or as proof of the easily bandied “internalized self-hatred” of the former colonial subject.

Utji, who holds a Ph.D. in social work and lectures at the University of Namibia, was the chairperson of the Ovaherero Genocide Committee (OGC), a group that had emerged out of the antiapartheid struggle and later political movements. The OGC played a vital role in Namibia’s political determination, with the country’s first free, democratic parliamentary elections held in 1989, a year before independence. In 2004, after more than a decade of efforts by OGC and other groups, Namibia won acknowledgment but never an unequivocal apology from the German government on the occasion of the hundredth anniversary of atrocities committed in the territory when it was a colonial nation known as German South-West Africa. Lasting for three years (1904–1907), the war was one of the earliest genocides of the twentieth century and resulted in the loss of 80 percent of Namibia’s population, from 80,000 to 15,000. With 2 million citizens in an area nearly three and a half times the size of the UK, Namibia is still one of the most sparsely populated nations in the world.

In the nineteenth century, the Herero, who were renowned for their handling and trade of cattle, had begun to develop a pastoralist lifestyle, slowly migrating south from territories in and closest to what is now Angola, where they settled and prospered as ranchers. Colonial documents detail a history of exchange over centuries between Herero peoples and foreign settlers, but as Germany, in many ways a pawn of England in the scramble for southern Africa’s significant riches, formalized their military presence there in 1884, Herero resistance grew. The German military revealed intentions to wipe Herero peoples from the land and profiteer from their forced labor. Coinciding with the rise of German nationalist, racist, and social Darwinist politicians and parties that later would become emblemized in the Nazi movement, the oppression and atrocities in Namibia were also supported by the increasingly commercialized European pseudoscience of race.

Utji had spent years conducting research in the National Archives in Windhoek and shared photographs and documents chronicling the mass removal of children, sent by rail and boat to work camps in Togo and Cameroon in West and Central Africa; concentration and work camps in Namibia where children and women labored with severely emaciated bodies; mass lynchings where children were lined up to witness events that echoed images of the American South; chained men and women burying relatives; the poisoning of wells and driving of Herero peoples deep into the Kalahari Desert to face starvation and death.

This history is also kept alive by oral tradition and family recollections. Many in the community had grown up with relatives who had survived the camps and killings; some were returnees from work camps in other colonial territories. The history was so prescient, so recent, that there could be no claim of amnesia. Utji’s friends who spent the afternoon with us were all active members of the OGC, Himba and Herero women who had started lives in Windhoek as students and professionals, supporting parents and extended families in the farm- and hinterlands who lived with the tangible legacy of the genocide and the ensuing eras of apartheid (as a South African protectorate) and revolution that defined the long struggle for democratic statehood.

Along with the German government’s recognition of the genocide, Namibians had secured UNESCO’s protection of the land that had served as battlefields, as well as the sites of five concentration camps, some of whose ruins will eventually be partially restored, the present markers replaced with official monuments.

The history of the genocide is little known, and its foundational relationship to Nazism is often dismissed, but its documentation lives in a 1918 tome called The Blue Book—a name shared by other official publications of the British Government—a post-facto study using survivor interviews and captured German documents detailing events and killings.

Most poignantly, the history lives in Herero women’s dress.

Utji played for us television footage of a 2011 visit to Germany by OGC members to claim the skulls of Herero men and women that had been exported by colonialists as “scientific” research material. During the genocide, skull-collecting had literally become a business. Herero women were forced to witness the death of family and community members and then clean their skulls. The women were recorded ululating as they tended to the bodies—part of traditions of protest and mourning and communication to the Herero resistance. Twisted into a false narrative about their savagery, this was mistaken for dancing. The skulls themselves remained housed for a century in German universities, research labs, and museums. Eugen Fischer, the infamous professor of medicine who devised a program of eugenics and became an important agent of Hitler, had kept a large collection of them. So widespread was the collecting of Herero heads that by the time the repatriation was ordered by the German government, many skulls were kept in ordinary residences. German citizens called to have the skulls picked up—not, I fear, as an act of relinquishing the past or facing of one’s colonial legacy, not as a display of sympathy or solidarity, but from a sense that they didn’t want to be out of step with the times, caught with symbols that echoed Nazism.

We silently watched video footage of OGC members walking on German streets in dresses representing the colors of the three major Herero clans. With them walked Herero men, some dressed in Western clothing draped with animal skins, others in German military uniforms adopted as symbols of their ancestors’ resistance, badges of courage. Many of the uniforms, especially helmets and accessories and regalia, are literal relics, family inheritance. It had become customary for Herero men to wear the clothing of their war conquests as a symbol of triumph, and as a means to inhabit the power of a terrible foe.

The OGC members sang and ululated and cried as they walked to the site where the skulls were displayed in anticipation of their arrival in Germany. The symmetries between the old dress and older European architecture—the cold, sterile cement and the empty streets recalled some of Namibia’s own palette and the barrenness and neo-colonial scrubbedness of its cities and towns and surrounding lands; the contrast of the brilliant-colored dresses of the OGC women and their passionate ceremony was visceral and haunting.

“They are so wise,” Utji said quietly, “they made sure to plan this on the Monday of a holiday weekend so that the public would not witness us when we made our motion for an apology and war reparations, and so there would be little press.”

But in the tiny international airport in Windhoek, surrounded by those beautiful, mournful hills, the return of the OGC with the skulls packed into the plane’s cargo hold was greeted by thousands of Herero women, wearing what now looked to me like the metaphorical skull-washer’s uniform.

It is difficult to reconcile the vying narratives of the dress:

Haute Fashion.

The Seduction of the Cow.

Garment of Defiance, Strength, and Survival.

Skull-Washer’s Apron.

Missionary Imposition.

The high, closed neck that persists in Herero dress design is the antithesis of Himba and Herero and other Namibian women’s historical bare-breastedness, still de rigueur among Himba today. (Thimba women from the north—the three groups are close relatives—have largely adopted classic brassieres, worn like halter tops). Religious conversion was slow to take hold in Namibia, a land where there has historically been a remarkable slowness in change and a social conservatism different from even Namibia’s near neighbors who share ethnic and environmental and social similarities that might explain such recidivism. A few prominent Herero families seem to have at first adopted the missionary dress and slowly others followed. Cloth dressing itself was adopted quite unevenly; the cow a powerful force against colonialism.

Through the nineteenth century, most Herero were bare-breasted and wore front and back leather aprons made from sheep, goat, or other wild skins, much like their present-day Himba relatives in the north. They were celebrated for their ostrich-shell-embellished overskirts and metal beadwork, the brass and copper and carved-horn cuffs worn at their wrists and ankles. The use of animal skins as the basis for Herero women’s clothing was not abandoned until the early twentieth century.

Again, I asked Utji and the others why this dress form survived rather than an embrace of pre-colonial styles.

“There would be no dress! Before the colonial era, we were naked,” they replied plainly.

There was no shame implied, if anyone was expecting it.

We sat quietly thinking about what had been said.

“Okay, not naked, but we would look like our Himba cousins,” Utji conceded. “Bare-breasted. Wearing skins.”

“But what about the original aesthetic,” which everyone acknowledged is quite fantastically haute, “but covering the breasts?” I asked.

Thimba and Himba styles from the hinterlands, not to mention Herero dress itself, could make fashion even by designers like Alexander McQueen’s dresses look mundane.

There is quite a lot of debate about it actually, Utji acknowledged. Younger generations were split. Many felt the dress styles were passé, that it held onto a past that people were too reluctant to move on from. Her own son, deeply intelligent and seeming to be nursing a twenty-first-century rage, wanted nothing to do with his mother’s activism, the dress, or Herero politics. As South Africa’s neighbors, Namibians were able to witness a very different relationship to fashion and to politics and the past with its fast-paced fashion industry competing on the world stage, constant style innovations, a booming luxury market nodding to traditional designs, and easy hybridization of various African, Asian, Islamic, and Western forms. At the same time, more and more young women seemed to be embracing Herero sartorial tradition, and there was a return of much of the early tailoring. The horn-shaped headgear, perhaps an innovation of the 1970s, though no one was exactly confident about how it had evolved or could name the precise era, was returning to its roots, to a soft, not overly embellished, vertical fashioning, more like styles associated with West Africa, pulled up high on the forehead.

The younger generations were blinging it up, too. The volume of the dress had grown—not the layering of petticoats, but the choice of wider dresses, shinier, more luxe and voluminous materials, imports from India and China and Dubai more than the traditional use of European materials, South African Dutch-originated cottons, and quilt-like peicings. There was more embroidery work, appliqué, and lace or lurex shawls. The jewelry was flashier.

No better place to see it, Utji told us, than at the fair.

Utji lived in Katutura, an area once designated for coloureds (people of mixed African and European ancestry as well as other non-whites), that had slowly integrated Herero, and then Nama and other peoples, to become a middle- and working-class residential area bordered by townships. She lived in a lovely house on a main road, with a heavy, ornate ironwork gate and a front yard appointed with old palms. The capital and largest metropolis in the Republic of Namibia, Windhoek is a city of nearly pristine beauty, with blanched, rocky hills that seem to be encircling you from at any point at the horizon. The light playing on their pale hues makes you aware of how easily the natural and urban worlds coexist there. It is a landscape so stark and so beautiful that it pulls from you, whether or not you think you have a reason to feel it, an incredible sense of awe and mournfulness.

There are few signs of poverty in the midst of the city, so as we rode to the fairgrounds in the neighboring township, Soweto, I was expecting the cover to come off of Windhoek’s constructed idyll. Windhoek resembles a hybrid of a small German city and a somewhat Africanized Dayton, Ohio; squeaky clean, efficient, well-oiled, with proper malls, chain restaurants, a proud university, outdoor cafés, pristine public bathrooms, good roads—upper- and middle-class black people and coloureds mingled freely with many, many white people.

Soweto resembled Los Angeles’s neighborhood of Watts in the 1970s. There was a kind of sanitized poverty. The worst of it looked from the surface like manageable living—not at all like the outward abjection seen in other cities—but like a tight shiny scab that might be a sign of healing, but more likely a cover with much festering below.

The fairgrounds were used mostly for trade and agricultural exhibitions, but on this weekend it was more of a Herero county fair. The headlights of the pickup we rode in revealed people of all ages flocking there, dressed mostly in the latest ready-to-wear styles, bundled in sweaters and jackets to stave off the chilly winter air.

Inside the gates stood rows of tents, with meat cooking on fires and smoke pouring out into the cold breeze. The outlines of Herero women—their dresses and wide horns—sitting on folding chairs as if at church or club meetings, were illuminated by the flames. Bread warmed beside the grills. Beer bottles clinked, rolling on the ground.

Each tent felt like a private club. I looked in each one voyeuristically, feeling the magic of the costume, the gathering of something inarticulably enchanting. And then I could feel the slow, deliberate, powerful movement of women crossing near to us, and I understood at once the fierce, elemental, sensuality of the cow. The women seemed almost like ships. In the sea of darkness and smoke you took note of their crossing. You moved out of their way.

There were rows, too, of exhibition tents, filled with the usual agricultural displays one finds at expos. In others, there were tailors’ booths, featuring ready-made Herero dresses and tiny replica Herero dolls. On display were many repeating dress materials, opulent and shiny, or in a more traditional woven striped material in black and shocking shades of pink and violet. Groups of men and women gathered at each booth. The shiny dresses created an intense show of material and somehow gimmicky embellishment that resembled the most garish extreme of a place like Lagos at the height of its oil wealth.

In the last booth, a camera was flashing, and a small group had formed around a woman posing against a picaresque desert background. As I drew closer, I saw her, dressed in rhinestone-studded jeans, her curly hairweave standing like a lion’s mane around her face. Behind her was a tiny grass structure with an animal skin at the door, and before her was a San man, with sharply filed incisors, characteristic light yellow-brown skin, the figure of the primordial, standing not much more than four-and-a-half-feet tall, wiry bodied, wearing just a skin-colored cloth at the loins, posed with his hand-fashioned bow and arrow. The San are an ancient people, early hunters and gatherers, rarely seen in the city, choosing to stay in their ancestral lands deep in the Kalahari. I was snapping a picture with incredulity over the timeworn “native” scene written as Herero keepsake, when someone barked at me that no pictures were allowed unless taken by or paid for with the cameraman, set up beside them with a laptop and printer hooked up to a generator.

I was not sure how the scene read to those around us, or what sense was made of what seemed a terrible re-inscription of endless colonial iconographies reproduced in cartes des visites and postcards and advertisements.

“I’m not sure it’s any different than the guys on 42nd Street taking pictures against those backdrops that say ‘Shoot the Homie,’” Simone said with the nonchalance of someone oversaturated by a culture of exploitative images.

Soon the kwaito music in the background was bumped up, and everyone was moving toward the stage, dancing.

I lingered, hoping to capture at least a bit of the smoky atmosphere, the women’s powerful silhouettes, on my iPhone. I realized there was something slightly militaristic about the women’s headgear, their horns. The mood of the tents, the campground, had revealed it.

I searched for the others in the hazy crowd, but their jeans and tracksuits blended with the rest. Then I made out Thabiso’s camera flash, and Simone’s confident, fluid stride in the field of cows.

I felt suddenly anxious to leave the city and journey to the Herero stronghold of the countryside.

The Land of the Himba

Opuwo marks a true frontier. It is a small city, near the Angolan border, a six-hour drive north from Windhoek on flat, well-maintained roads. It is the first place I’ve traveled in Africa where six hours is six hours and not twelve or fifteen or twenty-four. There is little traffic. You can ride great distances seeing only an occasional passing truck or car. It could be rural Nevada, except warthogs and baboons punctuate each half-mile. An occasional springbok or hyena and all manner of large and small deer-like animals appear along the road. They are your only hazard, and they are your thrill. On the other side of well-kept wire fences that come within a hundred feet of the road, you get a front-row seat for viewing giraffes and elephants and whatever else of the Big Five or smaller thousands amble near.

Namibia is a naturalist’s dream.

And once you pull into Opuwo, you have arrived in Namibia’s own metaphor: a forgotten, nearly untenable, wasteland.

I was traveling with Simone and Thabiso. We were each interested in Opuwo, where we were told Herero and Himba lives intersected dramatically without the dominant backdrop of expats and tourists and white Namibians.

Mushe had given us the phone number of her sister Kurumbu, who worked in an office on the dusty main road next to the city’s one large, modern beauty salon. She was a graduate student of advanced statistics, with a gentleness and intelligence and prideful knowledge of everything that we asked her to interpret.

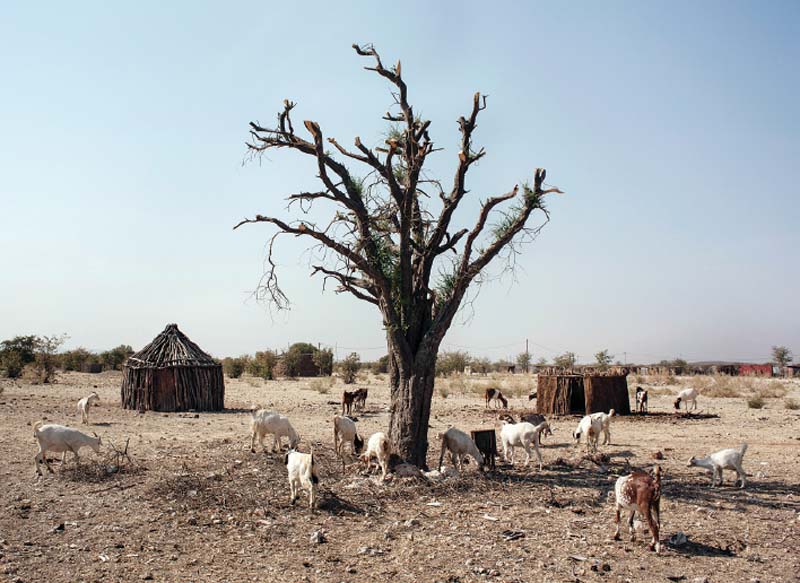

We arrived in the night and met her on the main road, and she led us to a guesthouse. Early the next morning she guided us several miles outside of town to an area of permanent Himba settlement: sparse clusters of round clay houses as large as a freight elevator. A squint-eye would mistake them for small storehouses, surprisingly connected to single power lines where cell phones charged. There was little traffic on the road, an occassional passing pickup truck loaded with Himba and Thimba travelers. Other-wise, there were just endless flat stretches of breathtaking white-blanched countryside, little evidence of water, and hills rolling out in the distance. Near each cluster of homes were enormous kraals—stick enclosures absent of the cattle they were built for—hoary, dramatic architecture that you could imagine was an inspiration to postmodernist art.

We arrived as a conspicuous group—Kurumbu in her jeans, her relaxed hair cut into a short modern style and covered with a camouflage-printed scarf; our driver, Cedric, a Nama college student with the look of a Miami beach bum and facial piercings that would fit in at any NYC hipster lounge but were in fact traditional Nama body arts; a dreadlocked Jamaican-American Simone in vintage shades and a green lace dress; a blond-tipped Afroed black-Jewish-Choctaw-American in a Ghana wax-print “skort” dress; and a black South African in style-clashing Johannesburg-mod shorts and a T-shirt, an artillery of cameras in hand. We elicited some laughs as we greeted several women sitting with small children under a canopy built from tree trunks and covered with branches with dried leaves, sitting around a dampened cooking fire.

Beyond them was a kraal, flanked by a fancy tombstone enclosed in expensive metal fencing. It was the grave of the patriarch, and its quotidian familiarity surprised me. It could be a grave most anywhere in the West—but for the metal posts on each side, with the six weathered skulls of cows stacked one on top of the other in towers, and several dozen more placed in the same manner in the forks of nearby tree branches. The curved horns intertwined, and a moss-like plant covered them, knitting together the skulls to the tree branches so that they appeared like ancient totems.

Himba women are legendary: bare, taut-breasted beauties with soft, rounded faces, covered with luminous, exotic red ochre that is rubbed into everything from head to toe and binds their long, dread-like locks. Himba women, in spite of how remote their lives, are a prevailing muse on African tourist art continent-wide. Now we were sitting among them, and it was hard not to feel voyeuristic, implicated in some way in that economy. They were not just the most beautiful, self-possessed women I’ve ever seen, the power of their beauty seemed interplanetary. It was a place of aural riot, of sand and unusual light and gentle waves of sound. The most stunningly colored birds I had ever seen flit everywhere. Green was green, blue was blue, the red of the ochre was red, but it was as if I was seeing the colors for the first time.

That is how it is to be among them. And then someone moves or brushes against you or a baby comes closer, and the touch and smell of the clay and cow fat, the whisper and crackling of soft-skin clothing, force you to reconcile the fact that this world is so material, they are so much of that very earth, the fat and the skin of the cow that lives off of it, that you, in fact, are the untethered, temporal, floating one.

Himba women traditionally possessed only what was taken from the cow and other animals and the earth and waters around them. Ochre representing blood. Cow fat. Ekori, the headdresses cut from dried animal skins. Aproning made of antelope, goat, and wild-animal skins. Cow-horn belts and bracelets, carved with patterning informed by the natural world.

The hair of one’s mother or grandmother is used with plant fibers to lengthen a Himba girl’s hair, securing one’s bond with maternal ancestors, rubbed with ash and shaped into tresses, then covered with ochre and cow fat. The ochre is taken from ancestral lands far in the interior, obtained over months of mining. It is applied each day and cherished for the aesthetic, but also for its protective elements—from sun, insects, heat, and the desert cold at night.

I closed my nose to the rancid smell of the combining of fat with mixtures of pulp and wood, sometimes burnt, animal and vegetal fats, berries and seeds to scent and augment. Their smells, like the adornments themselves, are meant to balance and affect spiritual and physical health, to proclaim clan identities, to signal as you pass through life stages.

Kurumbu explained later that during some marriages, a web of fat from around the intestines of a cow offered as part of the bride wealth, would be worn over the head like a veil. It was considered protective and a high status to be afforded the intestines. So what was to be disliked about the smell of it? she asked, laughing.

Utji’s words echoed with a finger snap in circle formation. It’s all about the cow.

But there are reminders, too, of a world beyond and Himba’s engagement with it. The jewelry that every married woman wears is made from conch shells, obtained from the great distance of the sea, once as valuable as a goat. Ostrich egg and iron beads from the south and the Kalahari. Metal buttons, rifle cartridges, safety pins, factory-made clips and chains and rings, fashioned as jewelry, are also only reminders of the colonial trade and of a society touched gravely by militarism.

That morning, we stayed at the compound, watching the women grind ochre between stone, prepare and mix fat and herbs with it, as we fingered the objects touched by the clay, played with the children, each lost in our own. We were taken into a chamber by a young woman, a new mother, who was nearly six feet tall, lanky, and as elegant as a body can be. She rubbed her whole body with it, patiently allowing us to develop our own narratives from her fiction of adorning while our cameras flashed, Thabiso filmed, and Simone and I wrote in notebooks.

As with Utji and the others, the intimacy between us was true, and our discomforts, our awareness of ourselves, the dynamics we assumed as Western seekers was easily slipped. We could have been Joburg cousins; there were rarely any Black travelers in Opuwo who were not kin to someone. And we knew the customs—to return their hospitality with bags of rice, sugar, other staples from town and not just a careless gift of money.

They playfully joked that Simone walked more like “a kind of goat” than a cow, admired her tactileness with the clay, and in each of our photos of each other, we appear as specimens of a kind, hands held over the women’s mouths, shyly giggling; children staring intently inches from our faces as if at a moving picture.

The Opuwo center brags a modern grocery, one good restaurant, a few banks, hardware and dry-goods stores, and some small industry. More than anything it felt like a bulking station, resembling many towns in Africa that had grown up along war frontiers. For the first time, we encountered waste in the streets, especially the ubiquitous scourge of plastic bags. But like Windhoek’s Soweto, Opuwo’s poverty had electrical breakers. And water and electricity ran in every home; even in the one-room mud houses miles beyond town you could charge your cell phone.

The parking lot that the bank and restaurant and grocery shared was filled by waves with tour buses and SUVs transporting white European tourists, stocking up before heading on off-road adventures or back down to the game parks or the infamous dunes and ocean at Swakopmund and Walvis Bay. You could pick out the usual suspects in the crowd—the hustlers and mercenary types, the sex tourists, young Himba and Thimba girls and even a few children being paraded for them by family patriarchs, the German exiles, the retiring Afrikaner presence, middle-class Herero landowners, and coloured middlemen. Himba women and men entered the grocery store and were gawked at by visitors, amazed by the contrast of shopping carts and bare-breasted nonchalance. The store staff followed them with contempt and frisked and checked their bags as they exited.

Namibia was short on black foreign travelers. South Africa, even Botswana and Zambia, were the more traveled locales. But we claimed our space on the main road, watching and interacting.

On the road there was the coffin-maker’s shop, behind a low wall of corrugated tin emblazoned with the hand-painted figure of a coffin bearing a cross. Behind it, a small, one-room barbershop, made from fresh concrete, featured bright imported curtains hung in the door. A large bar room nearby. A row of shuttered, never occupied, expensive new stores. And the secondhand clothing seller, ubiquitous in every African town. Piles of clothing spread out on the ground and hung from the eaves of a tarpaulin-covered shed. Across the street was the office where Kurumbu worked and the hair salon where the deaf proprietress would later sit with me with newspaper and small sticks, sheshwe cloth, a small costume-jeweled brooch, and a box of pins before her, fashioning headgear. Dressmaking seemed to be the work of male tailors, and the head was left to women. On the roadside, under a cluster of trees, Himba women sold cosmetic herbs and ochre, ground and in lumps, the shells and materials, including metal scraps, for making jewelry.

Thabiso had set up his Hasselblad near to the coffin maker, and fashioned an ambulant studio. For hours he shot whoever passed and agreed to be photographed, sometimes demanding a few rand. As we worked and watched each other and the road, we were all silently questioning what we were doing, the legacy of travelers in Africa, photography’s fictions and its violence, and where we enter, as part of a new generation of black artists engaged with Africa, coming from our own particular corners of the world, trying to establish some symmetry, or a harmony, even just between the three of us.

In Windhoek, Herero women’s dress was mostly reserved for special outings. It still stood out in relief—like something of a spectacle—on the street in the commercial center of the city. In Opuwo, you rarely saw women in jeans or other Western wear, and those women were mostly coloureds, store clerks, or part of a tiny cadre of professionals such as Kurumbu. Instead, the streets were filled with more staid cousins of the women at the Soweto fairgrounds, sewn from bright solid or simple floral cottons, plaids, and sheshwe, the “African” patterned southern African cloths that the Dutch introduced first in indigos. It was quotidian wear; none of it really fancy or even well maintained. But it was grand at the same time.

Herero women walked in small groups, carrying bright umbrellas and large knockoff designer handbags, wigs or relaxed tresses under headgear pulled down on the forehead so that the horns almost appeared to point toward the ground. Their necks were tied with scout-like neckerchiefs, adding that subtle militaristic air. There was a gentleness in their movement, their exchanges, but you were never unaware of their presence and the rhythm in that walk.

Himba women will always be Himba women. Even for a journey to modern Windhoek, they carry themselves wherever they go. What you begin to notice in the town girls is only the most inevitable, the more orthodox of alterations: Synthetic hair from China is added to the extensions traditionally made from ancestor’s locks, creating thick dramatic puffs at the end of each coil. The unifying of their beauty, the idea of the whole—Himba peoples, Herero peoples—makes sense within the context of tradition, but also in the way it was necessary, in the face of genocide, to unite individual, family, tribe.

It was then that I truly understood that the Herero and Himba are the same peoples. As much as Himba largely maintain a nomadic life, and the Herero split from them and became pastoralists and early Christians, as much as the twentieth-century Herero women had largely adopted missionary dress and abandoned the use of skins, family ties between them were still strong. I watched them walk together, obviously clan members, often quite intimate.

Later, I would ask Kurumbu about the ubiquitous brightly colored nylon tents at every house and market. They looked so modern and costly and stood in such relief against the square, dull cement architecture. I assumed they were left by tourists, many who come north to camp.

“We buy the tents so when our Himba relatives visit they won’t dirty our houses,” Kurumbu told me. “When the weather is very harsh, you will not deny them shelter inside. But otherwise, they sleep outside.”

“Hey, Kurumbu, you are the one defending the cow-intestine wedding veil,” I quipped.

“Yes, but when you work to buy a couch and good things for your home, you don’t want them left dirty and smelling,” she said, laughing.

Knowing that I might feel the same way, still I wondered about this slow but inevitable turning away from things, the abandoning of the land—in it is the echo of the genocide, a campaign of freakish German cleansing embodied in things as mundane as colonial advertisements of soaps; a bid to rid the land of all that is native, not of modern use, and discomfiting.

In Opuwo I said goodbye to Simone and Thabiso. I wanted to visit the coastal Herero towns, including Swakopmund, the site of UNESCO-protected battlefields and the planned monuments. Always there is the problem of the traveler and the squint-eyed gaze, the desire to get below the surface of things that looking into history through fashion both wonderfully enables and holds at an excruciating distance.

And there is the uncomfortable prescience of the past.

I was the only non-white person on the combi from Swakopmund back to Windheok, filled with middle-aged South African tourists and European students volunteering on Afrikaner homesteads.

Along the way an Afrikaner woman stole my Samsonite on the sixty-mile ride by combi from Swakopmund to the capital. She left behind her bedraggled suitcase filled with an odd mixture of clothing, yarn, tampons, and geriatric medicine.

What attracted her to my luggage I do not know, beyond perhaps the shiny dark exterior.

She had unwittingly exchanged her things for clay and remnants of the cow—the beaded leather jewelry and belts, the skull-washer’s hat, and sheshwe aproning. My note-taking. Everything was covered in cow fat and ochre; the clay, quite ephemeral, and its smell, still permeated everything. The cow and I were becoming harmonized.

I was leaving at 4 a.m. for Johannesburg.

Close to midnight, I was summoned. The bag had been miraculously collected by our driver.

I was going home with everything intact—and with the hope of making some meaning of what I had learned.

“Things are working out towards their dazzling conclusions,” Ama Ata Aidoo wrote of her heroine’s journey.

For Namibia, things were working out, however you calibrate the meaning. The skulls, squeaky clean, bright, were restored to their ancestral home. There was the shiny optimism in the dresses of the new generation, the return to the old headgear, no loss of the dazzling third eye. The archive had been opened for all of us to look at now with apartheid’s end. There was a healthy debate about Herero-ness and Himba-ness being played out sartorially and in ways that far transcend fashion.

Things were working out, too, in the realm of the aural.

From the hotel courtyard, I heard a kwaito version of a vintage British hip-hop cover of a familiar song. “Four Buffalo gals, go around the outside, around the outside, around the outside … Buffalo gals go around the outside and do-si-do your partner!”—a tribute to big African-American girls and our own social walk.

We may not love the cow, but once the buffalo, yeah, maybe.