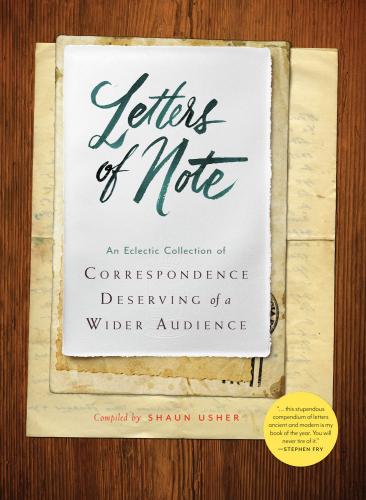

Letters of Note, a five-year-old blog run by Shaun Usher, is now a book. The blog offers correspondence “deserving of a wider audience” (as its tagline runs). When possible, Usher’s blog presents the letters in their original scans, preserving the quaint typewriter fonts, pretty letterheads, and handwritten annotations of their paper selves. This project is popular: The Letters of Note Twitter feed has an estimated 175,000 followers, and its Facebook page has been liked upwards of 73,000 times.

Letters of Note, a five-year-old blog run by Shaun Usher, is now a book. The blog offers correspondence “deserving of a wider audience” (as its tagline runs). When possible, Usher’s blog presents the letters in their original scans, preserving the quaint typewriter fonts, pretty letterheads, and handwritten annotations of their paper selves. This project is popular: The Letters of Note Twitter feed has an estimated 175,000 followers, and its Facebook page has been liked upwards of 73,000 times.

Letters of Note is an influential player in a new school of popular history shaped by the particular constraints of the internet. While popular history in book and documentary form has long tended toward narrative, viral history selects for single, supercharged documents: blasts from the past, given a hit of authenticity by the digital format, which allows readers to encounter the document (almost) firsthand and then pass it along immediately.

I’ve been running Slate’s history blog, the Vault, for the past two years. Like Usher, I’m in the business of selecting historical documents that are optimized to enter the internet’s bloodstream, be fruitful, and multiply. (In fact, I’ve often found a letter I’ve thought to write about on my blog, only to type its information into Google and see that Usher got to it first.) All of my misgivings about the format and content of this book are worries I’ve had about my own work at Slate, and should therefore be taken as something of a mea culpa.

The book Letters of Note—a beautiful object, well-presented—is fun to read. How could it not be? It’s all of the wheat of historical research, none of the chaff. Star moments for me included Aldous Huxley’s widow’s account of his LSD-assisted death; Beethoven’s letter to his brothers, explaining how his deafness had affected his attitude toward other people; and Victorian missionary Lucy Thurston’s 1855 account of a mastectomy undergone without anesthesia. Reflecting the Web’s scattershot approach, the letters are all mixed up in the book, arranged in no discernable order, whether chronological or thematic. The reader will encounter them, as the browser has, in totally random fashion, disconnected from any timeline.

The letters contain the telltale marks of their internet origins. Internet history, including the Letter of Note, must conform to a set of rules determined by the hope of traveling across social media. Because sharing a document requires aligning your name and profile with the document’s content, items are most shareable when their meanings are directly legible in the space of a tweet or a Facebook post. This is a key structural limitation: Only those gems that can be well-headlined, with display text that conveys their essential meaning immediately, will travel.

One strategy to maximize headline appeal is to find items that represent an ideal of universal humanity. For Letters of Note, this means letters in which the writer seems to reach out across the centuries and grab you by the collar, hailing you as semblable and frère. When readers retweet these links, they inevitably add commentary to this effect: “Looks like nothing ever changes!” For example, the Letters of Note book includes a hilarious letter from Charles Lamb to Bernard Barton, in 1824, describing the bad effects of a lingering cold: “I am flatter than denial or a pancake; emptier than Judge Parke’s wig when the head is in it; duller than a country stage when the actors are off it; a cipher, an o!” Another entry along these lines is a form letter that ninth-century Chinese bureaucrats used to apologize for having been drunk at a party.

Some such letters allow us to feel common cause with people we admire who, once upon a time, had to send well-written notes to the New Yorker asking for a job (Eudora Welty) or spam a powerful politician with an unsolicited description of skills in siege warfare (Leonardo da Vinci). The early foibles of the famous reassure us that our own current failings might be a phase, soon to be forgotten in the wake of our fame and fortune.

In his brief introduction, Usher calls the volume “a carefully crafted, book-shaped museum of letters that will grip you and fling you from one emotion to the next.” To that end, letters about highs and lows of human experience are popular. Some of these are undeniably moving and beautiful. Henry James’s 1883 letter to a depressed friend who had recently lost a relative is pure gold: “It is only a darkness, it is not an end, or the end. Don’t think, don’t feel, any more than you can help, don’t conclude or decide—don’t do anything but wait.” Advice between parents and children is also popular. It’s such historical writing that’s often described as “timeless”: a misleading descriptor that promises immediate comprehension and connection.

The demands of social-media transmission require that any content that’s bound by historical context should be easily understandable and neatly resolved. This approach selects for the kinds of letters that are righteous in the face of past moral atrocities. The book contains two letters from formerly enslaved people to presumptuous ex-masters who have asked them to return to work or to send money after their emancipation. (One of those, the letter from Jourdon Anderson to Patrick Henry Anderson, is one of the Letters of Note website’s most-visited pages.) Variations on the same theme are an 1885 letter from Mary Tape, a Chinese-American mother, to the San Francisco Board of Education after a school refused to enroll her daughter, and Jackie Robinson’s 1958 letter to Dwight D. Eisenhower after the president gave a speech counseling African Americans to be patient (“You unwittingly crush the spirit of freedom in Negroes by constantly urging forbearance”).

I, too, have experienced the viral bump that past righteousness garners. Vault posts that have traveled far include a 1933 letter from Helen Keller to book-burning German students (“Do not imagine your barbarities to the Jews are unknown here. God sleepeth not, and He will visit His judgment upon you”); an early-nineteenth-century petition to Congress from American women protesting Cherokee-removal policies; and an 1879 letter from a Chinese-American merchant decrying exclusionary immigration quotas. These letters give readers a triumphant sense that, despite the indignities of history, people were there speaking out, protesting, and being counted. Moments of half-heartedness, confusion, and backsliding are far less interesting or transmissible, though these are also the meat of human existence.

A few times, I’ve tried blog posts that are ambiguous in their takeaway lessons. Early in my tenure on the Vault, I posted a set of maps commissioned by the Japanese armed forces at the end of World War II, showing which parts of their cities the Americans had bombed. The historical use of these documents moved me deeply: The red-and-white maps had been posted in ships carrying demobbed soldiers back to Japan. The post went nowhere, and when I thought about it, this made sense. American readers might not want to appear as though they were sympathetic with the Japanese by posting such a link on social media, even if, in a longer conversation with a friend, they’d be willing to talk about the questions these documents raised. Those questions impede the document’s flow through the channels of social media.

Some parts of the letters in this book creep out of the “of note” frame, containing within themselves such confusing historical ambiguities, even as their headline was sufficiently strong to propel them through social filters. Lucy Thurston’s account of her unanesthetized mastectomy might be inconveniently religious for some contemporary readers. Thurston achieves a newly pure relationship with God during her operation, celebrating her pain in a way that nineteenth-century readers would have recognized as common, but twenty-first-century readers might find strange. “God disciplines me, but He does it with a gentle hand,” she writes just before describing the surgeon’s decision to extend his foot-long incision underneath her armpit. Mary Tape, the Chinese-American mother fighting for her daughter to attend a mainstream school, is assimilationist in the extreme, shunning “other Chinese”:

My children don’t dress like the other Chinese. They look just as phunny amongst them as the Chinese dress in Chinese look amongst you Caucasians…You had better come see for yourselves. See if the Tape’s is not the same as other Caucasians, except in features.

These letters suffer most from the lack of context and neutral presentation of the project. In order to pull off its universalist trick so well, Letters of Note must obscure its own point of view, implicitly eschewing any kind of argument. But why were these letters included? They’re the letters “we” like, or respond to. “We” noted them. But who are “we”?

Letters both “timeless” and historical reflect the mores of the internet, as seen through Usher’s curatorial eye. Usher selects several letters, for example, that argue against censorship: comedian Bill Hicks defending his critiques of religion; Kurt Vonnegut writing to a school official who burned Slaughterhouse-Five; on the website, Green Day’s Billie Joe Armstrong replying to a critic who called him “offensive.” Such letters bristle with the kind of truth-telling that’s got great appeal to the internet, which fancies itself to be rebellious, forward-thinking, creative, and antiestablishment. These letters make the reader feel great: strong, smart, and correct. “I read in the newspaper that your community is mystified by the outcry from all over the country about what you have done,” Vonnegut writes to the book-burning principal of Drake High School in North Dakota. “Well, you have discovered that Drake is a part of American civilization, and your fellow Americans can’t stand it that you have behaved in such an uncivilized way. Perhaps you will learn from this that books are sacred to free men for very good reasons…”

Who could object to a Vonnegut salvo like that one? I certainly don’t. But the letter from Charles Bukowski to an interlocutor who asks him about his negative representations of women, black people, and homosexuals is “of note” for more than just its acerbic rejection of “censorship.” Bukowski defends himself by claiming that his writing reflects reality. If he wrote about unpleasant people who came from those groups, it wasn’t his fault; “these who I met were that.” “I only photograph, in words, what I see,” he writes.

This is a particular perspective on the nature of authorship: one that aggrandizes Bukowski’s skills as a writer, while absolving him of blame for any objectionable choices. Usher clearly chose this letter because of Twitter-friendly, aphoristic lines like this one: “Censorship is the tool of those who have the need to hide actualities from themselves and from others.” Whether or not this is true is a matter of debate—or it should be. The presentation of Bukowski’s ideas in this celebratory format forecloses that debate.

A few of Letters of Note’s most-liked online posts, presented without comment (or sometimes with a line warning the reader to skip the letter if “easily offended”), take advantage of this presumption of neutrality in a way that’s jarring. A Ted Hughes advice letter to his son includes a passage about Sylvia Plath’s jealousy that’s (at least) unfair to her and (at most) deeply off-putting to a reader who’s apprised of the whole trajectory of that marriage. (“Meeting any female between the age of 17 and 39 was out,” Hughes wrote of his time in the United States with Plath, during which, he claimed, he was unable to “explore America” due to their cloistered lives. “Your mother banished all her old friends, girl friends, in case one of them set eyes on me—presumably. And if she saw me talking with a girl student, I was in court. Foolish of her, and foolish of me to encourage her to think her laws were reasonable.”) A Mickey Mantle response to a questionnaire asking about his most “outstanding experience” at Yankee Stadium might be hilarious to some, but is also deeply misogynistic. (Mantle writes about a fan who performed fellatio on him in the stands: “She…asked me what to do with the cum after I came in her mouth. I said don’t ask me, I’m no cock-sucker.”)

Usher writes in his introduction to this volume that the letters, which he calls “priceless time capsules,” will “whisk [the reader] to a point in time far more effectively than the average history book.” This is the promise of the curated document: all of the zap of historical recognition, none of the work. And of course, the compilation of a book like Letters of Note and the writing of an “average history book” are two radically different projects. The author of an “average history book” (which is a strange designation in and of itself; there are so many kinds of “history books”) synthesizes and compares. She takes the weird bits and picks at them. She doesn’t let a letter from Bukowski (or Mantle, or Tape, or even James), no matter how wonderful, fly by without taking the chance to ask: “What does it mean?”

Above all, a writer of good history ought not to assume that people in the past were Just Like Us. There’s a reason why you won’t find trained historians using words like “timeless.” Such assumptions foreclose everything that’s interesting about historical investigation, reducing the ambiguous strangeness and familiarity of the past to a solved problem.

Can viral history avoid these traps, while still traveling far? I’m trying.