By the time Kathy Acker died, in the autumn of 1997, I was nineteen and fully under her spell, having discovered her just a few years before. Her work brought me to all sorts of feelings—lust, rage, shame, guilt, rebellion, liberation, ecstasy, transgression, indulgence. If you were the type of nineties kid I was, piercings and tattoos and all kinds of body modifications interested you, and so her look—buzz-cut bleached blonde in a leather jacket with smeared red lipstick and smudged black eyeliner, with all sorts of visible ink and metal—appealed as well. She looked like a rock star and even now I think she was the only one the literary world ever really got. At one point, a wealthy Manhattan artist I briefly fell in love with gifted me one of her original proofs for The Adult Life of Toulouse Lautrec, which I keep next to my bed at all times. It feels lucky somehow.

Then in 2015, McKenzie Wark released I’m Very Into You: Correspondence 1995-1996 and it felt like Acker was remembered again. Their e-mail correspondence was a delight to read because it felt so now, like the e-mails that could have been composed today instead of two decades before. I don’t even remember sending e-mails back then, but of course Acker was always ahead of her time. There is a unique thrill in reading private correspondence always, but especially reading Acker being just as raucous and wild over e-mail as she was in her other prose. And also, just as seductive and lyrical a writer: “There are no words. I just want to say there are no words. I’m glad you came; and I’m glad you came.…kxx.” I think it’s fair to blame the current Ackerphilia at least partially on Wark’s book.

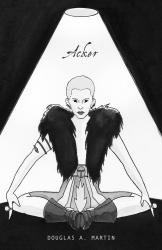

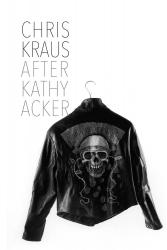

Now we’ve been gifted with two major Acker biographies. One, After Kathy Acker, by the obvious choice of author: Chris Kraus, a driving force behind the independent press Semiotext(e), who ran in Acker’s circle and was influenced by her work and presence. The other, Acker, is from an unexpected source, the lesser known Douglas A. Martin, a Brooklyn-based author of poetry and prose who has been a lifelong devotee of Acker’s. Kraus the contemporary and Martin the fan provide interesting bookends to this story. While Kraus’s is rather surprisingly a straightforward biography—it is, in fact, hard to remember this very mainstream book comes from Semiotext(e), known for introducing American audiences to French theory with a challenging roster of experimental writers—Martin’s is a lyric essay in many movements, fragmented and chaotic and academic and personal in ways Acker would have likely related to. Together they work beautifully and maybe even at their best taken as a duo.

Kraus’s biography has a note of hesitation around it, as if she herself is surprised she’s taking on such a mammoth task, although many would find her to be an ideal scribe: “Around this time last year, when I started working on what may or may not be a biography of Kathy Acker…” she coyly puts it, and perhaps this emotional gray zone is why this book is so incredibly conventional. And not in a bad way, either. The fact that it is almost pedestrian is somehow delightful. I found it to be a page-turner more than anything else, in the way most straightforward biographies of exciting individuals are. There is no trace of Krausian prose—instead plain, simple, almost business-like—and the book might even suffer from a near-scientific level of detail. Perhaps Kraus wanted her own reputation to take a backseat, but the book is meticulously researched and fact-checked almost to sterility. Kraus could have inserted herself—certainly her ex-husband and muse and Semiotext(e) coeditor Sylvère Lotringer makes many appearances throughout. He was Acker’s lover and mentor at many points. Kraus never once mentions her connection to him or her thoughts on their involvement, which actually becomes bizarre to read at points—a near-glaring omission. “I’m having this weirdo affair with Sylvère (Lotringer),” she quotes Acker writing, and then also consults Lotringer at other points: “Lotringer has no recollection of these BDSM sessions,” but without any acknowledgment of what sort of middleman she is. After all, rather unforgettably in Kraus’s hit novel I Love Dick, her love letter to Lotringer, you might say, Acker makes a notable appearance: “To Sylvère, The Best Fuck in the World (At Least to My Knowledge) Love, Kathy Acker,” she quotes an inscription in one of his books. Occasionally, Kraus is not afraid to get a bit more Krausy but it’s never too personal—it’s aesthetic. For writers, it’s a joy to follow her deep dissection of Acker’s use of the colon, for example. Sharp cultural criticism seeps in at times here and there, too: “Incredibly, critics of all kinds have embraced discursive first-person fiction in the last years as if it were a new, post-internet genre.” These instances only make me hunger for a few more dashes of Kraus to spike my Acker, but I also admire her decision to make herself more or less invisible, even when writing about friends and circles in which she was clearly enmeshed. You can’t help but want to say, Well, Kraus, what do you think of all this, yet you can’t help but admire the tight-lipped focus that keeps her on task, too.

Martin does something altogether different with his project, Acker, as if he the creative writer would never dare pretend to be anything but just that and only that. In 114 short vignettes, he tells her life story as if it were pieces of broken glass only very loosely fitted together to present some kind of impression of an image. Martin brings his own idols Julia Kristeva, Helene Cixous, Susan Sontag, Roland Barthes, Wayne Koestenbaum, and even Kathleen Hannah into the anecdotes and musings, while Bernadette Mayer, Patti Smith, and Anne Waldman are the sort of haunting matriarchs of Kraus’s world. (Both boooks have a lot of Acker’s experimental mentor/idol William Burroughs and cameos of her spirit animal and possessed chanteuse Diamanda Galás in their accounts.) Sometimes Martin is as inscrutable as an Acker text: “Let yourself come out, let yourself mingle with the other ‘I’s’ on the page. Wonder: who is ever going to be able to tell the difference, whether you begin and end,” opens one section. At other points, he is confessional and allows himself to be a character in her story: “In large measure, I began to pursue a doctoral degree as a reaction to not having a proposed paper accepted for the Lust for Life event” (the 2002 Acker symposium at New York University). And quite satisfyingly after the Kraus, Martin does the work of connecting Kraus to Acker: “It is hard not to address Acker and Sylvère Lotringer when they come up again in Chris Kraus’s 1997 hybrid-diary-manifesto-letter-novel I Love Dick.” Martin’s ruminations can’t quite stand alone as an Acker biography—it’s more of an experimental homage than anything. And while it lacks the bones and muscle that make After Kathy Acker such a powerful book, it includes the fancy and whim with care given to the beautiful prose Kraus’s book seems utterly unconcerned with. Martin is never not pretty with his reflections: “As I fear I am getting a little too close for my own comfort to consolidating an argument around the phallus, which I don’t want to do, let me go ahead and knock the wind out of my own sails in theory through poetry a bit, with a story.”

In the end, the two together—perhaps with a third, Wark’s great compilation that may indeed have ignited this fire—create a proper portrait of Acker, fitting into each other’s negative spaces so stunningly. Both of these authors know the archives well, but, though they go about projecting it quite differently, they also understand the soul of the artist. And of course, they are artists themselves. The startlingly different takes could be because Acker herself offers so many angles to choose from. To tell Acker’s story one has to wonder, which Acker? Which Acker was she to the storyteller? Which to the reader? Which to friends and lovers and family? In the end, I found myself thinking that one should aspire to be that kind of artist, the one only a kaleidoscope could hope to render, even with shady accuracy.