Two women share a hospital room, separated by a green-blue curtain, at the end of a brief, beige hallway. Their prospects foreclosed by illness, the women have agreed to enter this room, if not to share it, and to find what peace is possible. Separated always by the green-blue curtain, the women receive their respective family members, making few requests, their needs muted in a way that humbles and vexes their visitors. They are aware of each other’s presence, vaguely yet certainly, in the way of animals on opposite sides of an open field, at night.

The average stay on the ward is ten days. The two women have bad moments and somewhat better moments; they begin to notice each other in earnest. On the day that one has a crisis and the other calls for help, a proper introduction is made. Having prepared to die, the two women find themselves adrift on their respective beds, as days and then weeks begin to mount. The curtain between them hangs open for longer and longer stretches, snatching shut during visits and nursing calls.

The first woman receives family twice a day, visitors confounded by the grim, dirty-windowed hovel in which she appears trapped, and by her apparent lack of concern for her surroundings, at the end of a life marked by an outsized appreciation for beautiful spaces, especially personal spaces, for the possession and arrangement of things, elegant things, her things. The second woman sees her family less often. She has a tense daughter, a bubbly granddaughter, and a son-in-law who passes the time in a corner, drilled into a book. The daughter brings in a few framed pictures for the windowsill, items recovered from the second woman’s home, which her family has just emptied and sold.

For the first woman, a paradox emerges: surrendering the “fight” to survive has extended her hold on life, and renewed its pleasures. For the second, something more and less fortunate is revealed: She is not dying after all.

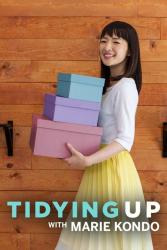

Although more clearly a work of entertainment than her mega-selling books, Tidying Up with Marie Kondo is also presented as a learning experience. Conceived in the mold of any number of lifestyle reality shows, the recent Netflix series centered on Kondo and her particular brand of tidying depicts one home transformation per episode via the “KonMari” method, wherein one’s possessions are interrogated for their ability to “spark joy,” and those that do submit to strict reorganization. If the spectrum of participants is pleasingly diverse and the framing of their dilemmas varied, ultimately they confront the same problem: too much stuff in too little space.

As visual drama, Tidying Up episodes peak early, when Kondo first instructs her subjects to pile all of their clothing onto the bed. Even those participants who do not immediately appear deranged begin to redden as the pile grows, more drawers are remembered and further closets emptied. There is the sense of a malignancy having been scraped from hidden places, synthetic fiber garments made in the world’s poorest places, with the apparent destiny of being packed into the walls of American homes.

A portion of the subjects are shamed by their clothing piles. Another portion seem to have accepted as inevitable, even desirable, that their homes should come to resemble the big-box selling floors they frequent. And then there is the woman who is elated to learn that she has produced the biggest clothing pile that Kondo has ever seen. “I win!” she exclaims, to her adult son’s dismay. “I love having all of this,” the woman says of her pile. “I really love what I have, I love clothing.” Seeing it heaped to the ceiling overwhelms her, she admits—but with what?

Kondo’s lack of judgment feels like a determined part of her TV branding and the oddly cozy tone of the show. Standing under five feet tall, the power of her spare, extremely feminine presence startles her subjects, who appear braced for a beating. Translator in tow, she explains that her method is not about trashing cherished things, but determining which possessions you most want to carry into the future. Largely unspoken is the idea that simply turning fresh eyes on your home will reveal the amount of clutter and useless crap looking back at you. In the most conspicuous cases, the show elides the question of what might bring a man to own nearly 160 pairs of unworn sneakers, or why a woman might find truest joy in the act of buying, and claim to love each tacky blouse.

This elision makes Tidying Up easy to watch and tough to fathom. Although the KonMari method turns on the idea of clarifying one’s relationship to one’s things, as depicted on the show it appears uninterested in reckoning with the extent to which an emotional attachment to possessions and possessing might run amok. The animistic Shinto philosophy on which Kondo draws was not conceived with consumer capitalism in mind. The collision of the two appears manifest in the expression Kondo wears through much of the show, taking in hug-prone Americans and awaiting translation of their words: bright, blinking eyes above a frozen smile, lightly alarmed but eager, always, to understand.

If the arc of the show bends toward cleared spaces and drawers full of shirts folded and stacked like disposable diapers, Kondo is not advocating for minimalism, exactly. The comfort of the individual is paramount; even her purging rituals are designed with it in mind. “Many people feel guilty when letting go of items,” Kondo says, over the show’s sugary, life-insurance-ad score. Expressing gratitude for the item “will lessen that feeling of guilt.” It is especially important to express gratitude for those clothes we bought and never wore, for they, too, taught us a lesson: that they are apparently not the kind of clothes we like to wear.

Tidying Up with Marie Kondo is seeded with tips and tricks, and intends to set the viewer to reflecting on her own home and habits. In the wake of its debut, social media poured with evidence of viewers inspired to KonMari their own living spaces. I watched Tidying Up as I have experienced most things over the two months since my mom’s death: thinking of her.

She would not have liked the show. Not enough plot, tension, character, complication. Too repetitive. Too bloody obvious. She scoured Netflix and elsewhere, in the last months of her life, for juicy, well-turned stories: Guernsey, Babylon Berlin, Howard’s End, the Wendy Whelan doc. Marie Kondo, at any rate, had nothing on her. Accumulation was never my mother’s style: She was always changing, ever chucking. Her home was a thoughtfully appointed sanctuary, her closet pruned and curated to perfection. Her cast-offs came to compose a third of my wardrobe; she could not abide even strictly necessary objects (a toaster, dish soap) on her counters.

In terms of the anguish they produced, her disease and the lack of control it represented ran close to par. Illness had made her a captive of the home to which she had devoted the bulk of her creative energies. Unable to master her beloved spaces and objects, she could no longer bear their proximity. She had no wish to die at home; her final entry into the hospital relieved that relationship’s burdens. But there was no question of touching her things as long as my mother lived. Like an external, life-giving organ, her apartment remained pristine. If she issued the odd, reflexive order about its maintenance, she was satisfied knowing her home continued to function, a refuge for the rotating crew of family who attended her each day.

More amazing, perhaps, than her defiance of death was her great comfort in the depersonalized limbo of her shared hospital room. As days became weeks became one month and then many more, there crept into my mother’s space a steady progression of objects, beginning with her devices. I became head mule, ferrying comfort items—pajamas, caramels, baby pink lipstick—in which my mother took intensely gratifying pleasure. Always our visits involved a session of micro-directed tidying and throwing away, in which I operated as an extension of her body, a task undertaken sometimes with reverence, other times with dismay.

In the next bed, my mother’s roommate accepted with equanimity the news that not only did she not have terminal cancer, she had no cancer—and no home to which she might return. One limbo begat another. A miracle and a huge mess. Because they refused to die, the ward attempted to purge both women, but could not shake them free.

The declutter video offers relief from the thing it perpetuates: a consciousness burdened by too much of everything, including five hundred million declutter videos. Like makeover and makeunder, declutter appears to have emerged from the consumer vernacular once popularized by glossy magazines and lifestyle shows. Hashtags and social-media platforms now perform much of that work: YouTube in particular elevated decluttering to a form of entertainment, spectacle with a moral gloss. As with their shopping haul and unboxing counterparts, declutter videos titillate but also relax. It is soothing, viewers find, to watch a naughty consumer setting his excess of things—his world—to right.

The declutter video has evolved an enigmatic script and visual language: headless figures navigate a personal space, a set of hands rearrange a drawer; “I’m just not reaching for it,” is a common refrain. Often the declutterer appears confused by her possessions, and ultimately expresses disappointment in them. “You know, I look at this palette and I’m not inspired, really, to do…anything,” says one woman, scrutinizing one of her hundreds of makeup items. “I never, ever grab for this,” she says of another. “I never even think of it, you know?”

I began to fixate on these videos over the final months of my mother’s illness, and it wasn’t to relax. I found some grim confirmation in the inability of most declutterers to part with much; in the implied certainty that they might live long enough to use up eighty-seven blushes; in the astonishing, abiding hunger for those things worth reaching for. The emphasis of any declutter video is not on what goes but what gets to stay, the drama is that of having chosen wisely, of reaffirming one’s commitment. They are studies in displacement, never more so than when the declutterer appears certain, by the end of her ritual, of having accomplished something worthwhile.

The notion that a person could have a meaningful relationship with stuff is one I associate with my mother, which is to say it is an idea I have rejected—or attempted or pretended to reject—for the better part of my life. Her extended occupation of that transitory, final space whittled to its studs all of life, every possible relationship—including that of person to possession. On the limited but distinct importance of material things, with each sleep set and grooming product, we built an agreement. We spent happy hours on the status of her toiletries, scanning and replacing, scheming new purchases; her growing train case and makeup bag accrued anchoring properties, confirmed a set of intentions. Understanding more clearly its ephemeral quality made each item more essential. None “sparked joy”; all represented another day, a life that continued despite its limits.

In one episode of her show, Marie Kondo advises a woman looking to deal with her husband’s things nine months after his death. Kondo does not declutter, of course, she tidies—a verb choice whose deceptions glare when applied to the widow’s task: “I always recommend that clients wait to tidy belongings of a loved one until the end,” Kondo says. “The reason is because tidying those items is very difficult.” As that remark suggests, the episode offers no insight into a pitiless endeavor with minimal payoff, no sense of how the belongings of the dead appear at once useless and unearthly, imbued with awesome powers. They persist in a state of betrayal, death having exposed the lie that grows only more central to modern life: that the right stuff will save us, keep us safe from harm, ensure the future we imagine. The relic is the most useful of objects precisely because, like death, it chooses us. The relic rejects ownership, past and present. Above all it reminds us that we are masters of nothing.

I knew I would meet again many of the items I brought to my mother, and now I have. They are no less ephemeral for having survived. Our relationship is unclear. I can feel their presence—two travel kits filled with lotions, brushes, balms—in the next room. I claimed them from her side, stray fragments of an infinite puzzle. More than any heirloom or favored bequest, they linger. I let them; I want them to.