The Roman State had now become so strong that it was a match for any of its neighbors in war, but its greatness threatened to last for only one generation, since through the absence of women there was no hope of offspring, and there was no right of intermarriage with their neighbors …

Matters began to look like an appeal to force. To secure a favorable place and time for such an attempt, Romulus, disguising his resentment, made elaborate preparations for the celebration of games … .

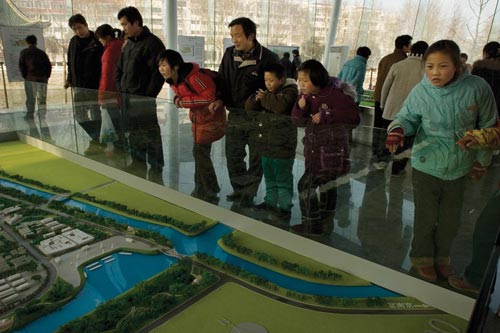

There was a great gathering; people were eager to see the new City, all their nearest neighbors … and the whole Sabine population came, with their wives and families. They were invited to accept hospitality at the different houses, and after examining the situation of the City, its walls and the large number of dwelling-houses it included, they were astonished at the rapidity with which the Roman State had grown.

When the hour for the games had come, and their eyes and minds were alike riveted on the spectacle before them, the preconcerted signal was given and the Roman youth dashed in all directions to carry off the maidens who were present. The larger part were carried off indiscriminately … .

—Livy, The Early History of Rome

When Wu Pingzhang took his wife to Nanjing so she might give him a boy, things were looking up. Development had finally trickled down to Suining, his forgotten corner of China. Landlocked and four hours from the nearest major city, in the hardscrabble Huai Valley, Suining was once the second poorest county in Jiangsu province. Now, farmers were finding work in Shanghai and the wealthy cities around it—constructing skyscrapers, laboring in China’s overnight factories, changing the diapers of nouveau riche babies. They were sending back money en masse, thousands of wire transfers all directed to Suining’s Agricultural Bank, and returning home with bags of cash. Once back, they bought apartments in new buildings and furnished them with appliances they had little experience operating. As an air conditioner repairman with two cell phones he kept on day and night, Wu Pingzhang was among the first to profit.

Liu Mei, his wife, was renowned for her cooking, and as his wallet swelled so did their bellies. By the time her belly grew for a different reason, Wu Pingzhang had enough money to rent a spacious room in town, away from his ancestral village, in a cluster of slapdash cement-block buildings, above a portrait studio called Flying on the Wind. To brighten the room, the studio lent him an airbrushed canvas backdrop—a floor-to-ceiling vista of clean white windows opening onto a glittering blue sky—and he arranged his own appliances, bought from customers secondhand, in front of the backdrop like a set in a play: a Wanbao refrigerator, a Midea microwave, a PANDA color television. The centerpiece was an upright air conditioner that stretched from the cement floor to near the ceiling. Wu even had enough to afford a frivolous indulgence, a collection of Cultural Revolution-era Mao pins he kept sheathed in a red velour case. He felt entitled to an heir.

He needed one, in fact. “It’s a question of yuanfen,” he explains to me, invoking a Chinese concept that entails a tangle of destiny, luck, and the sort of fatalism that grows out of thousands of years of continuous history. “A son will take care of you when you’re older. You need someone to sweep your grave.”

But getting an heir was complicated. First of all, Liu Mei had already given him a child, a smiley seven-year-old girl named Wu Chun. The one-child policy meant they had only one chance, and that chance had already come, without bringing Wu Pingzhang any closer to continuing his line. Wu Chun’s birth had been recorded by nosy family planning workers, who might also, given the opportunity, note details like irregularities in Liu Mei’s menstrual cycles. While forced abortions were rare now, the monitors could make it difficult for Liu Mei to have a second child. Wu Pingzhang decided they had to escape the monitors’ gaze.

Placing Wu Chun with his parents, he moved with Liu Mei to Nanjing, the provincial capital, where he rented a room a quarter the size of the apartment in Suining. Nanjing was a vast city that often overwhelmed him. But Wu Pingzhang picked up intermittent repair work, riding from house to house on a bicycle, logging fifty or sixty miles a day. Liu Mei stayed at home, and her stomach ballooned.

Wu Pingzhang just needed one boy, but when he took Liu Mei to a clinic at five months and saw the ultrasound, there were two. He is vague about whether he worked hospital connections to determine the sex of the fetuses or waited until Liu Mei gave birth to find out, but something about the image left him elated. “Not everybody has twin boys,” he says.

The couple returned to Suining for the birth, and when the twins were delivered Wu named them Da Bao and Xiao Bao. “That’s the bao from baowei zuguo, from protecting the motherland,” he told people. Big Protector and Little Protector. He envisioned the boys honoring their country. But they would also protect him in his old age and safeguard his family line.

By the time the boys said their first words, however, Wu Pingzhang started to worry. Other Suining couples in his block of apartments had been going to similar lengths to secure heirs. The bakers from Hunan province who hawked saccharin cookies from a streetside folding table had a boy. The woman who sold ice cream bars from a cooler further down had a boy. The proprietors of Flying on the Wind, who did a brisk business in photographing baby boys: also a boy.

When Da Bao and Xiao Bao were two, the Suining CCTV affiliate broadcast a special on the nannu bili, the “boy-girl imbalance.” Wu Pingzhang learned the gender ratio among children under four in Suining had hit 152 boys to 100 girls. When he thought ahead to the twins’ futures, his vision of a cheerful, comfortable home vanished. He worried they wouldn’t be able to find wives.

Halfway between Shanghai and Beijing, the Huai Valley spans an agricultural plain that is something like China’s heartland. Around 250 BC, the valley produced Gaozu, the first emperor of the Han dynasty and one of China’s few peasant rulers. Today, however, it’s distinguished primarily by its ordinariness. Huai people speak a dialect that’s close to Mandarin and intelligible to most outsiders. They eat a food that’s a little spicy, a little salty, a little sweet. The Chinese often divide their country along a culinary line, into north and south, Noodle-eaters and Rice-eaters. A common question is, “What’s your grain?” People in the Huai Valley eat both.

The area is also representative in its demographics. A skewed sex ratio like that in the Huai Valley is the rule, not the exception across rural China. Wang Xiucong, a wiry 58-year-old Suining man who remembers a time when the genders were balanced, tells me it’s a fact of modern life. “There are boys everywhere,” he says. “Everyone has boys.”

It’s commonly reported that in China there are around 120 boys born for every 100 girls. That’s among the most lopsided ratios in the world, well above the United Nations recommended limit of 107, and it means that nearly 17 percent of new males don’t have a female counterpart. Even so, the figure doesn’t fully reflect the gravity of the situation. China’s minorities, who live primarily in western China, are exempt from the one-child policy and rarely practice sex selection. And while wealth doesn’t necessarily lead to more daughters, a handful of more developed cities report stable figures. The gender imbalance is difficult to register on a tour of Tibet, or on a business trip to Shanghai. In towns in the interior, however, the disparity is obvious—especially by, say, standing outside a kindergarten as children stream out of their classrooms at the end of the school day. In Yichun, Jiangxi, there are 137 boys for every 100 girls under age four. In Fangchenggang, Guanxi, the number jumps to 153. And in Tianmen, Hubei: 176. China’s estimated 37 million additional males are concentrated in these areas. Demographers call them “surplus.” Overstock.

The same thing is occurring, to varying degrees, across Asia, where continent-wide there are as many as 160 million extra men. In India, the 2001 census recorded 933 women for every 1,000 men—a difference of 35 million people. South Korea maintained a ratio of over 110 boys to 100 girls throughout the 1990s, and Taiwan has reached similar levels in recent decades. According to a recent United Nations Population Fund report, problems may also be imminent in Bangladesh, Nepal, and Pakistan.

Lately the phenomenon has even spread to some previously balanced regions. In 2005, a group of scholars from the Caucasus Mountains showed up at a conference in Singapore to announce that the sex ratio at birth for Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan had abruptly topped 115. (The subtitle of their paper: “Why? How?”) And in the 2000 US census, the gender ratio for second children among Chinese, Indian, and Korean immigrants who already had a girl hit 117.

What exactly the dearth of women means for Asia’s—and the world’s—future is a subject of considerable debate. Some scholars suggest reducing the number of women will ultimately improve their status (an analysis that ignores, maybe, the reception given a lone woman at a frat party). Others say a large male population might yield increased tolerance for homosexual behavior, a sort of male prep school writ large—and then find themselves in the uncomfortable position of arguing that homosexuality is a product of environment, not genetics.

Most, however, assume the extra men will continue to do what they’ve done for centuries: get, or try to get, married. In societies like China, which place a heavy emphasis on marriage, the pull of tradition is strong. Women tend to marry up, and men who can’t find partners end up relegated to the bottom of the social structure, and frustrated. It is the prospect of the status quo, times 160 million, that inspires works like Bare Branches: The Security Implications of Asia’s Surplus Male Population. Or, to name another example, the posters from the Indian government’s recent campaign against female infanticide, which show half a dozen cables aiming at a single plug.

I started looking into Asia’s gender imbalance three years ago, from my desk in Shanghai, through downloaded papers and books ordered from the US. There were papers questioning the motives of the government bodies that keep sex ratio records, papers suggesting the whole problem might be attributed to high rates of hepatitis B infection among Asians, papers proposing the missing girls were simply hidden. There were mathematical formulas. A provocative paper by Shuzhuo Li of the Institute for Population and Development Studies at Xi’an Jiaotong University predicted:

The unbalanced Chinese gender structure caused by “missing girls” will result in a series of social problems. These will include inferior physical and psychological health of the unmarried, an increasing number of non-marital births, difficulties of old-age support for those who never married, increasing prostitution, sexual violence and trafficking of women. These and related social problems will damage the society’s overall welfare, and harm the long-term sustainable development of the Chinese population and society.

Nearly half of China’s “surplus” males, I learned, are under fifteen. But that left millions of men already of marriageable age. What, I wondered, was happening now? What had really caused the imbalance, and what would its long-term effects be? To find out, I decided to make a series of trips to Suining this spring. That seemed easy enough at the time; the county is a fifty-minute plane ride from Shanghai. But it is, I found, worlds away—its gender imbalance the product of complex, often conflicting, forces. The Huai Valley is a testament to the enormity of Asia’s coming demographic challenge.

Across town from Wu Pingzhang, his cousin Wu Bing 1 rents a small, cramped cavern in a dark alley. The room nicely mirrors Wu Bing’s diminutive frame, but he’s rarely there. An itinerant construction worker, he leaves abruptly for distant cities for indeterminate lengths of time. His wife, Liao Li, suffers from a mysterious affliction of the internal organs that demands a rotating collection of expensive medicines. A devout Christian, she gives the Protestant Three Represents church 1,000 yuan ($146) a year—what Wu Bing makes in a good month. The couple is, not surprisingly, among the least successful in the extended Wu clan.

Like any man, however, Wu Bing needed an heir. On their first try, Liao Li gave him a daughter. They named her Yanyan, which means “cliff,” hoping she would grow up to be strong in heart and mind. They tried again and got a second girl. They called her Panpan, for panwang, which means “hope”—in hopes she would augur a son on the third time around. Family planning officials fined them 10,000 yuan ($1,460), adding some urgency to the task. If Panpan didn’t bring a brother soon, their lives would rapidly get very expensive.

Portentous names were an old tactic. Scattered throughout rural China are women and girls named Laidi (“Come Little Brother”), Daidi (“Bring a Little Brother”), and Youdi (“Have a Little Brother”). But this time it didn’t work. For Liao Li’s next two pregnancies, they visited an ultrasound clinic and arranged for technicians to reveal the fetuses’ gender. Sex determination is illegal in China, but a well-placed red envelope full of yuan or a carton of prized Chunghwa cigarettes can go a long way. “Maybe you have friends in the hospital,” Liao Li explains now, over a decade later. “Or someone introduces you to friends.” Both fetuses were female, and the couple decided to take matters into their own hands. An abortion cost only one-tenth the fine levied for having Panpan—a manageable expense, both times.

Liao Li tells me about the abortions one night after a dinner washed down with warm beer. After that she speaks only hypothetically. Their approach to reproduction is a sore spot for her. The Three Represents church is state-sponsored. Its services routinely include prayers for government leaders, propaganda campaigns, and major national events (during my visits, we recite multiple blessings for the Olympics). The church can hardly oppose abortion, which is critical to carrying out the one-child policy. But Liao Li, who leads the Three Represents committee in Wu Bing’s ancestral village, knows her pastor believes abortion is taking a life. And she has a problem, again hypothetically, with sex selection. “It’s stupid thinking,” she says. “When one is, after all, oneself a woman.”

But the calculation paid off: eleven years ago, Liao Li gave birth to a boy. She and Wu Bing called him Maodan, which means “Fertilized Egg.” Why that name? I ask. “It means something like ‘Treasure,’” she explains.

With three children and unpaid family planning fines accumulating, money soon grew tight. Wu Bing moved to Shanghai for a while, taking whatever work he could find. Liao Li’s mother helped out by sewing beads onto velour hair ties, selling them to wholesalers for 0.13 yuan, or two cents, apiece. Liao Li was never an enthusiastic cook, but her meals became even simpler: vegetables and beans with tough flatbread, and little, if any, meat. Through the struggle, however, a goal crystallized. They would enable Maodan to attend high school.

To realize this dream, shortly after Yanyan, their first daughter, turned twelve, Wu Bing and Liao Li seem to have persuaded her it was time she start working. They had a distant relative in a garment factory in Shanghai who offered to find her work there. For Yanyan, who says working was her idea, the thought of moving to glamorous Shanghai was exciting. In the days before she left Suining on the overnight bus, Yanyan paraded around with her mother’s purse looped around her arm.

But the factory turned out to be far from Shanghai’s famed shopping streets, in a rundown warehouse in the shadow of two elevated highways near the city’s northern limit. Younger and smaller than the other workers, with short, unkempt hair and round baby cheeks, Yanyan had trouble adjusting to the twelve-hour shifts. She couldn’t sew, so the foreman put her to work snipping stray threads. She slept in a crowded dorm in the same building as the factory, surrounded by strangers who spoke different dialects. The lonely nights got to her. Friends say she retreated inward.

But all of this I learn later. When I sit with Liao Li one afternoon at the family’s miniature kitchen set—the knee-high table surrounded by shoebox-size stools common in rural China—she doesn’t mention it. Most of the room is taken up by two beds piled high with clothes, bedcovers, and religious texts. Affixed to one wall is a small scrap of paper that reads love jokes. Apart from that, there is very little adorning the room. Wu Bing bought his family a color TV, but none of the other appliances of his cousin. Liao Li cooks outside, in a shed that juts into the alley. “We’re a poor family,” Liao Li says, drawing out the word “poor.” “But Jesus helps us.” That first year, help also came in the form of Yanyan’s meager paycheck: a monthly allowance of 600 yuan, then around $73.

Panpan stayed home and enrolled in the town middle school. Now thirteen, she’s past the age at which her older sister left home, and she spends her afternoons drawing and playing with friends. A few weeks later, when I visit the family at their ancestral village home, Panpan is in the courtyard wrestling with a ragged black puppy. “Panpan’s studying hard so she can go to high school!” Liao Li says brightly. But she doesn’t sound so sure.

The Chinese character for man is 男—an ideogram combining “field,” a grid divided into four squares, and “strength,” a sweeping two-stroke abstraction of a plow. For centuries, boys were needed to work in the fields. Woman, 女, is a bloated rendition of “person”—a stick figure with a belly. Peace, 安, is a woman under a roof—birthing more boys, but also safe and healthy. Inherent in this division is a natural balance. Men tended the fields, women looked after the home. But even in pre-revolution China, trying circumstances often forced expecting couples to make difficult choices. When food grew scarce, they opted for laborers over caretakers.2

In the Huai Valley, which was subject to the roaring floodwaters of the Huai and Yellow rivers, food often grew scarce. In 1874, after a series of particularly devastating floods brought widespread famine, Suining had 163 males for every 100 females. This made it one of the most imbalanced counties in the area. But, like today, the difference was hardly unique; men outnumbered women throughout much of the region.

When Mao Zedong assumed power in 1949, he put an end to female infanticide, making reproduction the domain of the state. He officially simplified the characters by reducing their strokes, divorcing them from their etymology, then made the etymology irrelevant by sending women to work in the fields. Women, he famously noted, hold up half the sky. China’s gender ratio briefly leveled out.

Then, following the economic reforms of 1980s, the fields lost ground to industry. In the Huai Valley, the Suining Meat Products Company set up shop, as did an array of small chemical factories and other scattered workshops. The canals lining the county’s rice paddies took on a fluorescent green hue.3 The people living alongside them became factory workers and migrant laborers.

Women excelled as both. Factory owners even preferred them, believing them less likely to make trouble. But there was no such thing as migrating for good. The leaves fall off the tree but return to the roots, as the old saying goes. During the summer harvest, and again at lunar new year, Suining’s scattered emissaries reconvened in their ancestral villages, where carrying on the family line remained essential. And in the villages, people talked. “If you don’t have a boy, you lose face,” Liu Mei says.

For centuries, locals relied on folk methods to determine the gender of a fetus. If a woman craved sour foods during her pregnancy, it was a boy. If she developed a sweet tooth, it was a girl. A boy manifested himself as a smashed, oblong belly, while a girl was rounder. Such means were, however, unreliable. One legendary local mother, Jiang Hongmei, gave birth to between ten and fourteen daughters—neighbors disagree on the number—in an effort to produce a son.4

But as Suining developed, so did its baby-making industry. For those who could afford it, ultrasound—what villagers called “the scientific method”—became the preferred approach. Reproduction-centered “black ads,” photocopied fliers and stenciled blocks of characters, appeared on communal outhouse walls and in alley corners. cure stds, infertility reads a flier posted in the outhouse near Wu Pingzhang’s house. advanced instruments. imported medicine. get better in one shot.

Twins, which are exempt from the one-child policy, became more common. By having several kids at once, some couples reasoned, they might increase their prospects of having a boy. Alternately, aspiring parents of boys shared effective methods online. On one website, couples could purchase the Have a Boy Secret Recipe, a Chinese medicine touted as a longstanding secret of the Dong minority.

With fieldwork no longer their primary source of income and family planning bureaucrats watching them closely, most couples had fewer children. It then became imperative to have a boy on the first, or at least the second, try. Women like Liao Li—third-triers—became rare. And so the gender ratio rose.

Meanwhile, the steady flow of capital into Suining allowed its people to afford bigger and more elaborate weddings. When the Wu cousins married, a simple meal sufficed. Now it became popular to marry in the traditional style, with the groom riding in on a horse, and the bride on the shoulders of hired workers, in a red sedan emblazoned with a gold “double happiness” character.

Even if the Wu cousins’ sons—Da Bao, Xiao Bao, and Maodan—can find wives, their parents worry about funding the weddings. A man seeking a partner needs an apartment, money for a wedding banquet, and a competitive bride-price—and the tab for these dues typically falls to his parents. Wu Pingzhang has a plan: when his twins are older, he will sell his collection of Mao pins. In a decade or two, he thinks, the relics will draw enough money to pay for two respectable weddings. But his cousin doesn’t have that option. Shouldering fines for two children, he has no savings. And Maodan is already eleven.

Legally, the marriage age in China is twenty-two for men and twenty for women. But many people in Suining marry in their late teens. One of the first questions people ask me is, “Have you found your other half?” When I remark on this to Liu Mei’s brother, he explains that to remain single is to remain a child, with only elderly parents to care for you in the afterlife. Wu Pingzhang puts it more bluntly: “Not getting married, not having kids—not possible!” Increasingly, however, some men have no choice.

- A groom escorts his bride from their wedding in her family’s courtyard home in a village near Suining. None of the bride’s family or friends accompanied her to the reception at the groom’s home.

One sunny morning, Wu Pingzhang picks me up at my hotel on his motorcycle and drives me out to Wu Jin, his and Wu Bing’s ancestral village. The village is a short drive from town: a left turn onto a deserted four-lane highway just past the market, a parade of nascent factories, then an abrupt swerve onto a dirt road behind the Cigarettes, Alcohol, General Merchandise, and Seed Store. From the highway, I can only see fields and stagnant green canals. Then he weaves the bike through a thicket of trees, and the village rises up in a row of brick and cement houses with peaked roofs.

Wu Jin is laid out on a grid of meandering paths, their degree of straightness determined by the number of ramshackle outhouses, vegetable patches, and pig sheds between point A and point B. Most of the houses are traditional courtyard homes, walled U-shaped buildings framing a central patch of sky. A handful smack of remittances from Shanghai: lavish two-story structures, their cement so dark it might just have been poured. The village has a population of around 300, but most able-bodied adults are off working in town or in cities in southern Jiangsu. The people who are still here are too old, too young, or too poor to leave.

Wu Pingzhang pulls up to a big red double door and pushes it open, leading me across the paved yard and into the living room, whose most prominent feature is a curtain of noodles drying on a clothesline. In the corner, an old man wearing a navy blue cap and a Zhongshan suit, the high-necked jacket Westerners associate with Mao, is sitting at a rickety wooden table, scolding Da Bao and Xiao Bao.

Wu Pingzhang left the twins with his father today so Liu Mei could attend a wedding. If his wife had her way, the twins would live with their grandparents. They’re boisterous, frequently fighting with the neighbor boys, only quieting down when she puts on a grainy VCD copy of Tom & Jerry. She already has her hands full with Wu Chun, who spends most of her days inside, watching television from her bed. And together, the three kids foil her dream of opening a snack stall.

But our check-in only convinces Wu Pingzhang that the twins should not be entrusted to his father. We have barely said hello when he notices Da Bao is hot and clammy. “He can’t take care of him,” he mutters, hoisting the boy onto the motorcycle and motioning for me to climb on behind. He speeds down the highway to a row of village houses that have been converted into businesses, parks in a lot where old people are sorting plastic bottles into piles, and carries Da Bao into a makeshift clinic. Inside, a man in a dirty lab coat is watching a soap opera from behind a greasy glass case. Wu Pingzhang pays him a few dollars to inject Da Bao with antibiotics.

Before returning to Wu Jin, we stop at a restaurant a few doors down. Inside, premixed dishes are languishing in metal bins at room temperature. Wu Pingzhang sidles up to the owner, a sturdy middle-aged woman, and chats amiably in dialect, ordering raw peanuts, spicy noodles, and a rubbery yellow log made of chicken and rice. The only other person in the restaurant is a woman wearing shorts and a thick coat of makeup. She watches the exchange warily from a metal stool.

“Did you see that girl in the restaurant?” Wu Pingzhang asks me when we’re back on the bike. “She’s a xiaojie.”

“What do you mean?” Xiaojie has multiple connotations. In Shanghai, it means “miss,” a polite title used for waitresses, store clerks, and unmarried women. In northern China, it can mean “prostitute.” Surely here, in this sleepy village, it must be the former.

But no. “I mean jinu,” he says. “I know from looking in her eyes.”

“What is she doing in the restaurant?” I ask. It wasn’t yet noon.

“Waiting for customers,” he shrugs. “That’s her spot.”

He’s amused by my incredulity. Later, he adds, “There’s a whole street downtown. Jinu jie.” Prostitute Street.

In the mid-nineteenth century, a Chinese poet penned a classical poem about the people of the Huai Valley. In Suining and surrounding counties, he wrote, “Children carry swords, adults shoulder guns, and desperadoes gather by the hundreds to kill in broad daylight.”

This bleak view is understandable. For decades, bandit and militia groups roamed the valley, prompting besieged farmers to construct fortresses in self-defense. In northern Jiangsu, a rebel society called the Nien was seizing control of valuable trade routes, looting villages, and kidnapping for ransom. The Nien often swiped women, who could be traded for horses or sold outright. Virgins were particularly attractive targets. The rebels discovered families were willing to pay extra ransom if they returned their daughters before nightfall.

The Nien themselves were mostly unmarried peasant men presided over by gangsters with formidable nicknames: Big Cannon Chang, Water Pipe Wei, and Cat-Eared Golden King of Hell Wu. By 1855, their ranks had swelled to 40,000, enough to stage a full-fledged rebellion. After capturing towns throughout the Huai Valley, the Nien severed communication lines between the Qing dynasty rulers and troops who were off fighting other rebels. They did not bring down the empire, but the devastation they wrought throughout central China contributed to the Qing’s ultimate collapse.

Later, historians searching for the causes of the Nien Rebellion would point to the region’s short supply of women. As many as 20 percent of local men—and up to 39 percent of men in Suining—were unable to find wives. Concubinage among the rich exacerbated the problem. According to a county magistrate of the time, “bare sticks,” or bachelors unable to perpetuate their family line, were among the area’s principal troublemakers.

Even after famine gave way to years of more bountiful harvests, the Huai Valley remained a volatile place. In 1925, the prefecture that contains Suining counted 5,000 bandits. Groups like the Pinchers, the Black Rifles, and the Sword Daggers were so powerful that they made the area one of the toughest battlegrounds of the Communist revolution.

When Mao Zedong eventually won the frustrated bachelors over, he did so in part by promising to liberate the concubines, freeing them to marry. But the unrest in the Huai Valley would be written in history books and remembered by later generations as a caution against the perils of a skewed sex ratio.

Earlier this year, from their headquarters in a hulking gray tower on the outskirts of town, local government officials dreamed up the Suining Breakthrough—a program intended to stimulate investment, attract industry, and spur innovative thinking. The slogan is, “Break free in one year; lead in three years; eliminate poverty in four years.” The onslaught of official announcements, TV news broadcasts, newspaper spreads, advertisements, and web pages that followed made clear that to achieve the Suining Breakthrough, the people of Suining would have to sever ties to their shameful past. In July, Communist Party County Secretary Wang Tianqi took the podium at the town’s Lucky Chance Plaza and informed the crowd assembled before him that they had to purge their traditional thinking, and fast. “Suining is backward today,” he said. “But it can’t afford to be backward tomorrow. And it certainly can’t afford to be backward forever.”

Convincing villagers to change their thinking, officials have long hoped, is as simple as bombarding them with propaganda. In the 1960s, village buildings in the Huai Valley read boundless faith in chairman mao. In the 1980s, following the introduction of the one-child policy, Cultural Revolution slogans gave way to red-character threats like better to let blood flow like a river than to have one more than allowed and you can beat it out! you can make it fall out! you can abort it! but you cannot give birth to it! Now, the village walls push messages of tolerance: boys and girls are the same, boys and girls are both treasures, and caring for girls starts with me. At the same time, lest villagers turn soft, corollary campaigns emphasize the Two Illegalities: sex identification during ultrasound and sex-selective abortion.

Whether the propaganda has much effect is unclear, however. Following China’s 1980s economic reforms, local propaganda bureaus retained rights to a chunk of signage, but with most other wall space, the free market now wins out. Suining’s stenciled government slogans are outnumbered by more colorful ads for life insurance providers, motorcycle repair shops, and wedding photographers. And with all of the other forces competing for people’s attention, the government line hardly seems relevant. I visit the town shortly after the unveiling of the Suining Breakthrough. But locals seem more concerned with the opening of an underground superstore.

With parents across Asia caught up in the fever of economic development, the programs that are most effective at eliminating son preference employ positive financial incentives. In 2000, China introduced the pilot program Care for Girls, which eliminates school fees for girls and provides pensions for their parents in 24 counties in select provinces. (Suining is not among them.) Over five years, the program reduced the counties’ sex ratios at birth from 134 boys per 100 girls to the national average of 120. China is now expanding the program to other counties. India has a similar program in place in the state of Bihar; the Girls’ Protection Scheme rewards parents by investing money in a maturing fund upon a girl’s birth. But so far, such programs are too limited in scope to impact the nationwide gender imbalance in either country.

More promising is the example of South Korea, which began addressing its skewed sex ratio in the late 1980s and early 1990s through stringent laws, heightened oversight of ultrasound clinics, and a vigorous education campaign. Last year, for the first time in over two decades, the country achieved a normal sex ratio at birth. A recent United Nations Population Fund report cites the country as a model for the rest of Asia.

The decades it took to fix the problem, however, left a generation of men with reduced prospects for marriage. In China, efforts at serious change will run up against the same obstacle—and be compounded by the sheer size of the population. A growing genre of ads on village walls around Suining now touts “marriage introduction agencies.” Their names suggest modern dating companies: Good Luck, Perfect Match. But locals say the agencies offer less progressive services.

I next visit Wu Jin during the June plum rains, when the land is green and the village unusually alive. The plum rains are for switching crops—wheat comes out, rice goes in—and the village’s fortune-seekers have left the comforts of town life to wade through the paddies, planting rice amid clumps of reeds. On the highway, women are spreading wheat to dry in neat mustard-colored circles. During a break in the work, a woman named Zhang Mei pokes her head into Wu Bing’s house to ask for directions to a market. She is wearing men’s pants and a black-and-white polka-dotted blouse. She says she tried to find the market on her bicycle this morning but got turned around and had to return home. “You’re still getting lost,” Liao Li chides. Zhang Mei smiles an expansive smile and continues on her way.

Zhang Mei was born thirty-seven years ago in distant Yunnan province, in a poor mountain village near the border with Tibet, a place that has as much to do with Suining as Tennessee does with Alaska. Villagers say she was fooled into moving east to Jiangsu to marry her husband, a man over fifteen years her senior who had trouble finding a local wife. Liao Li says the trafficker who took Zhang Mei east told her she’d be able to find work there. Zhang Mei says she was “introduced.”

Zhang Mei is one of four Yunnan women married to local men in Wu Jin. Villagers find the women a curiosity, joking about their thick accents. Beyond that, they disagree about the women’s place in the community. Wu Pingzhang says the Yunnan wives are happy to be in wealthier Jiangsu, that they don’t return home for visits because of high family expectations. “If they go home after all this time they have to buy gifts for everyone,” he explains. “That’s really expensive.” We’re sitting in his house waiting for lunch when he says this. Liu Mei jerks away from her cooking to interject. “‘Really expensive’?” she snaps. “They were conned.”

Liao Li explains the phenomenon as a question of supply and demand. “Those men can’t find wives,” she says. “They’re the ugliest ones.” Yunnan’s supply is cheap, not to mention delicate and obedient. But Lu Weimin, a driver friend of Wu Pingzhang, shies away from describing the arrangement as a sale. Rather, he says, it’s a transaction between families, a dance of polite gestures. “This Yunnan woman, maybe her older brother needs to get married, but he doesn’t have money to find a wife,” he explains. “So you give the family 5,000 or 6,000 yuan”—about $800—“for her brother’s wedding.”

Zhang Mei doesn’t have brothers. She is the youngest of three sisters. At seventeen, she journeyed from her village to Kunming, Yunnan’s provincial capital. It was her first time in a city, and she visited Stone Forest, a tourist site outside the city, where she had her photo taken in the traditional dress of the Dong minority. She posed for another portrait outside Yiliang General Merchandise, a Kunming department store. She had a delicate frame, the moon-shaped face worshipped in classical Chinese poetry, and hair that reached her lower back. In the photos she draped it over one shoulder, so that it flowed down her chest in a shiny black wave.

Zhang Mei says she met her husband in Kunming. Her neighbors say a trafficker brought her east and sold her to a Wu Jin family. In any case, she married, and her husband, who worked the night shift at a pesticide factory, installed her in the village. Most Wu Jin women are outsiders who married in. Zhang Mei just came from farther away.

Later, when I stop by Zhang Mei’s house, I find her scooping freshly dried wheat into large burlap sacks. She invites me in for tea. Her house is half the size of Liao Li’s, with two beds, a worn couch, and a kitchen crammed into one room, but warm and cheerful, with pink mosquito netting over the beds and knickknacks hanging on the walls. There is a TV that’s tuned to a soap opera, and above that a plastic clock stopped at 6:30, and next to that an enormous photo laminated onto a thick rectangular board. Staring out of the frame are a couple clad in white, the man in a bow tie, the woman in a gaudy dress. Inset in the lower right-hand corner is a small full-length image of just the woman, as if for emphasis.

It’s hard to tell what anyone really looks like in Chinese wedding photos, to make out an expression beneath the thick layer of whitening powder, the intense airbrushing, the clipped half-smile. But in this case it’s impossible to hide the groom’s big ears, hen eyes, and receding hairline. And it’s hard to hide the look of bewilderment in the bride’s eyes.

In the desk beneath the wedding photo, Zhang Mei keeps a thick stack of snapshots locked in a small drawer. For two decades, her mother and aunt have mailed her images from the life she is missing. She can trace the growth of her sister’s children, the march of weddings, the lunar new year reunions.

In Jiangsu, meanwhile, her life progressed like that of any other village woman. As the years passed, she picked up the twisted vowels and injected “ahs” of Suining’s dialect. She cut her hair and twirled it into a loose bun. She joined Liao Li’s prayer group, even as she gained a reputation as a card shark, a woman always up for a round of majiang. She had three children, finally giving birth to a son on the third try. Like any other couple, she and her husband made calculations. To avoid the fine for their second daughter, they sent her to live with Zhang Mei’s mother—a return, one generation later, of a lost girl.

As we talk, Zhang Mei shuffles about the kitchen area, where she has hung a red velvet poster of Jesus on the cross. She’s glad she found the church. “I carry some burdens, and people sometimes criticize me,” she says. “If I didn’t pray, I would keep it all in my heart.”

She hacks a watermelon into large chunks and brings me a piece. We sit on the sagging couch, watching the soap opera (Women Don’t Cry), and spit seeds on the floor. During a commercial break, she turns to me and smiles. “It’s good you didn’t get married young,” she says.

Yunnan wives are famous throughout China. In January, a man with the username of lzhy6 opened a thread on Baidu Know, a forum similar to Google Answers, and described how his girlfriend was threatening to leave him unless he found a job.

I’m so upset, I want to go to Yunnan and buy a wife

5000 yuan, 18 years old, good-looking, can do housework, good at cooking and washing dishes

Doesn’t mind having kids, eight or ten will do haha

In the string of responses that followed, some users chastised him for treating women like chattel. But many were helpful. One said he also hoped to buy a wife, offering his contact information so they might coordinate their trips. A second explained that in this era the good women have been snapped up already. Then a third countered with the suggestion that “lzhy6” try Linyi, Shandong, where one could get a woman for only 3,000 to 4,000 yuan. “It’s old-school to go to Yunnan to buy,” he explained.

Yunnan is one of China’s poorest provinces, with an annual per capita rural income of 2,042 yuan ($298). According to provincial police department statistics, around 1,000 women and children are trafficked out of the province every year. The International Labor Organization, which monitors trafficking in the region, estimates the number is much higher than that. Families often consent to the sales, making cases difficult to track.

Women are typically lured east by the promise of employment. Sometimes, they’re snatched from markets and streets as girls and sold to families with young boys. The old practice of buying a tongyangxi, or “foster daughter-in-law,” and raising her alongside her future husband has apparently reemerged in some parts of China as a way of securing a wife early. But trafficking isn’t a problem just in Yunnan. With a shortage of women looming across Asia, the wife trade is rapidly turning international.

In the past few decades, wealthy countries like South Korea and Taiwan have seen a proliferation of “marriage tour” companies, which operate like Western mail-order bride services, facilitating meetings between male clients and women in poorer countries. In Korea, where rural governments concerned about shrinking populations sometimes subsidize marriage tours, 14 percent of newlywed men married foreign wives in 2005. In Taiwan, the total reached one-third in 2003. Many of these countries’ brides now come from Vietnam.

As China grows wealthier, it could join its neighbors in importing women. Already in southern Guangxi province, men routinely cross the border to find wives in Vietnamese villages. And in 2006, a joint China-Burma investigation uncovered a trafficking ring that had been selling Burmese women to Chinese men. According to the US State Department Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons, women are also trafficked into China from North Korea, Mongolia, and Thailand.

Wife-trading might be a solution, albeit a crude one, if not for the finite supply of women. In 2005, Australian geographers found that in some Vietnamese villages as many as half of local women ages 18 to 30 had left to marry foreigners. The next year, the Vietnamese government introduced new marriage registration requirements, stipulating that couples seeking marriage permits be able to communicate with each other. But it doesn’t seem to have helped. In April, the president of the Vietnam Family Planning Association told the Vietnam News that the loss of Vietnamese women to foreigners remains a serious problem. Meanwhile, Vietnam’s own sex ratio is rising. In sixteen provinces and cities, it has reached 128 boys for every 100 girls. And most Vietnamese men can’t afford to look abroad.

One Thursday morning, I accompany Liao Li to church. I meet her at 5:30 am at the entrance to her alley, and she gestures for me to climb onto her bicycle rack. I sit with my legs to one side, and we inch out of town. Panpan and Maodan are off from school and home alone. Wu Bing left for a construction job in Nanjing over a month ago, leaving Liao Li with the cell phone and no way to contact him. When he can, he calls from a public pay phone.

We cross a stream that a billboard advertises as the site of a coming entertainment complex and emerge into a cluster of wood stalls, marking, for the moment, the point where town meets village. The church is housed in an old warehouse a few hundred feet from the road. When we enter, it is already half full. A rosy-cheeked woman is standing in front of a gold cross cut out of glittery paper, clutching a microphone and leading the congregation in song.

Save for the cross, the décor is spare. Tube-shaped fluorescent lights are buzzing overhead. The edges of the ceiling are rimmed with mold. Liao Li takes a seat near the back and pulls a songbook out of her bag.

The singer’s sharp soprano booms through speakers strung up in the back of the church. Ni … zai … nali? “Where … are … you?” The congregants, who sit facing her on maroon wooden benches, follow an octave below, stumbling every time the melody dips. They are overwhelmingly female, with the trim bobs and shoulder-length hair of the middle-aged, along with a few ponytails suggesting youth. The benches are so hard that many have brought their own cushions.

Liao Li, who hasn’t, follows along. The melody is pentatonic, bluesy, and faintly reminiscent of a slave hymnal:

The factory is big

But workers are rare

The crops are abundant

But workers are rare

A middle-aged woman wearing oversized glasses takes the microphone and addresses the congregation in a low, rumbling voice. What follows is not so much a sermon as it is an exquisite one-woman show, a mishmash of impersonated dialogue, delivered in dialect, and forceful exposition in Mandarin. She urges the worshippers not to be “small people”—to resist gossip, to treat people the same regardless of their backgrounds, to remember they are all, in the end, peasants.

Dialect: “Have you had a son yet?”

Mandarin: “Do you have to raise the son? Do you have to care for him when he grows up?”

Liao Li pulls out a small notebook and jots down notes. Lately, she’s traded one set of child-rearing worries for another. A year and a half ago, after Yanyan grew despondent in the Shanghai garment factory, she and Wu Bing found her work in a factory in Nanjing, a small bolt manufacturer where most workers are from Suining and her father, at least for the duration of his current job, can visit on his days off. Yanyan is fifteen now, and she seems happier. But Liao Li has started worrying that Maodan isn’t studying hard enough. He spends his afternoons in the maze of alleys outside his family’s room, shooting Pogs with a rotating crew of neighborhood boys. “Maybe you can help him,” she suggests at one point. “He doesn’t work at English.” She wants, badly, to know that the tradeoff—one, maybe two, girls in factories in exchange for their brother’s education—isn’t in vain.

The minister crescendos to a finish, and the worshippers drop to their knees, turn so they are facing the back of the church, and place their heads on the pews. Liao Li curls into a ball on the floor. Then the women cry, like mourners at Chinese funerals, in waves of long, tearless wails.

Before I leave for Shanghai, I stop by Wu Pingzhang’s house one last time. Liu Mei is washing up from lunch, the half-finished dishes still on the table, a severed umbrella top protecting them from flies. Da Bao and Xiao Bao are watching Tom & Jerry. Wu Chun is lying on the bed behind the screen.

Wu Pingzhang asks me to look into a few things for him back in the city. He wants me to have his Mao pins appraised by an antique dealer so he can double-check that they will bring in enough money to fund the twins’ marriages in twenty years’ time. He borrows my camera and carefully frames the pins against their red velour case, photographing them one by one. There are a few dozen in all.

A few weeks later, I am eating dinner with a friend at a Thai restaurant back in Shanghai when Wu Pingzhang sends me a text message. “If you marry your old man do you want to have a son? I know a secret recipe do you want it?”

It is, I assume, a forward he sent to several different women. For one, I don’t have an old man. Second, in several extended talks about reproduction and children, I never expressed a desire to have a son over a daughter. I text back: “I’m not thinking of having kids right now but what do you mean?”

He replies promptly. “It’s a real secret recipe have you heard of Chinese medicine?”

Then he adds: “Don’t think about it too much.”

Notes

- This name, like the names of all people interviewed for this article, has been changed. ↩

- The decision to kill a female child wasn’t always economic. Imperial records from the Qing dynasty suggest that the rich may have practiced female infanticide as well. ↩

- The Huai Valley is featured in Elizabeth Economy’s influential work on China’s environmental troubles, The River Runs Black. In the past two decades, she writes, “Paper and pulp mills, chemical factories, and dyeing and tanning plants, employing anywhere from ten to several thousand people, have sprouted along the bank of the river and its tributaries … [and] freely dumped their waste into the river, making the Huai China’s third most polluted river system.” ↩

- When family planning officials appeared to stave Jiang’s fertility, neighbors tipped her off and she ran. After giving or selling a few daughters to traffickers and sending others to factories at a young age, she finally had a son. When I ask her one day whether she wanted to have so many children, she shoots back, “Do you even have to ask?” ↩