The express bus from Hyderabad to Dantewada takes fifteen hours on a good day. As the suburbs of the software hub are left behind, and then the wrought-iron gates of Ramoji Film City, the smooth pavement falls apart. But the sweep of paddy fields and palms—a facsimile of the INCREDIBLE INDIA! billboard hanging at the Delhi airport when I first arrived—grew more hypnotic with each mile, making up for the rough going. Hills loomed in the hazy distance. Cowherds shunted their stock out of harm’s way, and women carried grain in clay pots on their heads. Passing into virgin forest so dense that hardly a ray of light broke through, I finally dozed off, rustled by the occasional thwack of a tree branch as we hurtled into dusk.

Dantewada, the main town of Chhattisgarh state’s remote Bastar Division, seemed bucolic enough. The smell of freshly fried samosas wafted from the corner dhaba, where lanky men took cover from a sun that beat down like a fist. Long-distance coaches to Andhra Pradesh and Orissa came and went in a fit of honking. At either end of town, Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) barricades, reading WE NEED YOUR COOPERATION, were the only signals that something might be wrong.

Within minutes I found N. R. K. Pille, my local contact, reading a newspaper in front of his dry goods stall. Bald as a Buddha, with a belly and smile to match, the old man waved me inside for a glass of milk tea with biscuits and promised to find me a guide for the duration of my stay. How long a stay I didn’t know, though privately I had vowed not to leave Bastar until I met face-to-face with the Maoist guerrillas known to command the surrounding mountain jungle.

Pille rolled up his linen kurta to sit down. He told me he’d lived in Dante-wada for more than thirty years, doing part-time work as a correspondent for state papers. He was a grandfather now and a sort of godfather to town journalists, who stopped by to pay their respects. We slurped our tea in silence. Abruptly he leaned forward and issued a warning: these days no one could be trusted outside of town—not the rebels, not the police, definitely not the civilian militia patrolling the villages. “If you go one way the Naxals kill you, if you go the other way the police kill you,” Pille said. Most Indians called the Maoists Naxals or Naxalites—after the West Bengal village of Naxalbari, where the movement began in 1967. “Don’t be fooled. The government says it’s safe because they want to hide what is really happening.”

Today, Bastar is the epicenter of a forgotten war. As in Kashmir and Assam, India’s better-known theaters of conflict, an excess of natural beauty belies the bloodshed between the government and leftist rebels. The difference is that Maoist violence has surged in the heart of the country while Islamist and ethnic separatism on those far-flung fronts have declined. More than 350 people were killed last year in Bastar by Maoist-related violence, more than half of the 650 such deaths nationwide. Maoist influence has also spread, to anywhere from 150 to 194 districts in 16 states, and to varying degrees. Compare this to 20 districts in Jammu and Kashmir coping with Islamist separatists, and 50 districts in the Northeast where ethnic separatists are active.

The Maoists, whose ranks are estimated at 10,000 armed cadres, are strongest in forests, about one-fifth of which they control. Last March, fighters launched a midnight attack on a remote police outpost in Bastar, killing fifty-five policemen with firebombs and machine-gun fire. It was the boldest move yet in their campaign to ignite a “people’s war” throughout the country by striking at symbols of Indian authority. In November 2005, cadres freed several hundred prisoners from a jail in Bihar state. In Andhra Pradesh, they have tried to assassinate government officials with roadside bombs. Theirs is also an economic war. A two-day Naxalite blockade last June shut down key rail links and coal and mining operations, resulting in losses of about US$37.5 million to the Jharkhand state economy. Rebel leaders insist they’ve “liberated” vast rural areas to serve as staging grounds for advances on big cities; their enemies say the government has simply abdicated control.

With the exception of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, who has called the Maoists “the biggest internal security threat” facing the nation, the Indian establishment has downplayed the phenomenon. This is reflected in the dismal security presence in states of the so-called red corridor, which stretches from the Deccan Plateau to the Himalayan foothills. In Bihar, there are 54 police for every 100 square kilometers, compared to 31 in Jharkhand, and 17 in Chhattisgarh. It’s far worse in Bastar, where less than four policemen are on the ground for every 100 square kilometers, probably half being teenage irregulars.

They are the offspring of Salwa Judum (“peace mission”), a controversial program started three years ago by government officials here in the central Indian state of Chhattisgarh. The idea is to arm civilian militia. Assigned the title of “special police officers” (SPOs), most are young locals hastily trained then turned loose to fight the Maoists. Critics, like Mr. Pille, say it amounts to government-sanctioned vigilantism and has led to excesses on both sides, forcing more than 50,000 people into roadside refugee camps.

“You saw the camps along the road coming here?” Pille asked.

I shook my head.

“It must have been dark when you passed them. They are packed with scared, helpless people. It’s never been worse.”

Up two flights of creaky wooden stairs in a dank building off Lal Chowk, the main avenue in Srinagar, in India’s northernmost state of Jammu and Kashmir, Khurram Parvez recalled how the walls of his office used to shake from the bombings and gun battles that marked the passage of time. Separatist militants armed and funded by neighboring Pakistan were dying to strike at the nerve center of Indian security forces in Srinagar, the summer capital. They had tacit support from average Kashmiris, many of whom used to set their watches a half-hour back to Pakistani time in a gesture of solidarity. “At the time people saw Pakistan as a savior,” the black-bearded rights activist said. “Now they understand it has always been serving its own interests.”

Kashmir has been hostage to bitter relations between India and Pakistan since the partition of 1947. Although its population was 77 percent Muslim and 20 percent Hindu, a ratio that stands today, the last maharajah of Jammu and Kashmir, Hari Singh, opted to accede his kingdom to India. This kicked a grim fate into gear. Anti-India currents simmered until 1987, when Muslim political parties complained that state legislative elections were rigged against them. Militant wings coalesced. Two years later armed resistance to Indian rule began in the Kashmir Valley, with groups split between demands for independence or a union with Pakistan. Hardened jihadis who had fought the Soviets in Afghanistan poured in; what had been a nationalist-secularist ideology soon morphed into an Islamic one. Cross-border shelling and militant infiltrations escalated into nuclear brinkmanship between India and Pakistan, while untold crimes took place behind the scenes. An estimated eight thousand people have “disappeared” over the past twenty years, according to Khurram, who co-founded the Jammu and Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society to draw attention to lesser-known aspects of the conflict.

These wounds remain open. But last year conflict-related deaths across the state totaled 777, down from 1,116 the year before and a peak of 4,507 in 2001. As a result, investment has jumped from $200 million to $2.3 billion over the past seven years. On a brisk March afternoon, Srinagar’s downtown street markets buzzed. Young professionals sprawled out for lunch at an island park. The only disruption was a crowd of bus drivers, hoarse from trying to shout above the din of traffic for back wages they claim the government owes them. Across the street from the former press enclave—a brick carcass pocked with bullet holes from a militant siege—was a sign for Rising Kashmir, the newest English-language daily newspaper.

Khurram told me that Kashmiris half-joke they should be grateful to the Pashtun tribes along Pakistan’s western border with Afghanistan “for taking the bombs” that used to rock these same streets with devastating frequency. Such black humor might be forgiven after decades of violence that cost an estimated 40,000 lives. The violence cost Khurram his right leg. Four years ago, the rights activist was traveling by van in northern Kashmir, monitoring elections, when a land mine exploded under his vehicle. Khurram underwent a series of operations and now uses a prosthetic, but his friend and fellow activist Asiya Jeelani wasn’t so lucky. She died instantly.

Gul Wani, a soft-spoken professor of political science at the University of Kashmir, said it would be an oversimplification to give all the credit for its troubles to Pakistan. Over an aromatic mug of Kashmiri kava at his campus residence, Wani said that a peace process that began in 2004 between India and Pakistan had produced a climate of moderation, regardless of any political calculations on either side. He noted that Kashmiri pandits (Hindus) who fled when hostilities broke out are trickling back to live in government-built housing colonies; a bus route now runs across the Line of Control, reuniting family members; and in a surprise move, Asif Ali Zardari, co-chairman of the Pakistan Peoples Party, said in March that the Indo-Pakistani relationship should not be held “hostage” to the Kashmir issue, calling on both sides to strengthen economic ties.

Zardari’s statement was met with cautious approval in India and with confusion among hard-line separatist leaders in Kashmir, who have long depended on Islamabad’s patronage. “Their falling status in Kashmiri politics is evidence that people felt their drive for a separate state had come to be co-opted by Pakistan,” Wani said. Even militants appear to be holding back. The United Jihad Council, a Pakistan-based association of thirteen hard-line militant outfits, has repeatedly escalated violence to disturb elections; recently the group made it known that it will not use arms to enforce a boycott of polls scheduled for the fall. “On a religious pretext, Pakistan has projected itself into the struggle by violent means that had achieved little.” Little more than turning one of the world’s most breathtaking places into a no-go zone for investors and tourists. “Historically, it’s been Kashmir for Kashmiris. And violence has never really been considered an instrument of change among average Kashmiris,” Wani said, “from day one until now.”

Waiting one evening for a chikara to take me to a friend’s houseboat on Dal Lake, the enduring jewel of Kashmir, I watched a man dredge the bottom for the weeds that dull its patina. To gain leverage, he arched over the rails, nearly falling overboard, until he scooped the muck and flung it in front of him in a single fluid motion. The calm was interrupted when several of the banana-shaped cruisers pulled into the jetty. A dozen tourists from Malaysia, Singapore, and southern India clambered out, cameras in hand.

“French or Italian?” a voice called.

“American,” I said, turning to locate its source.

“American! Where are the rest of you?” the man asked, introducing himself as Farooq Mir.

Farooq told me that he’d weathered Srinagar, his birthplace, through the hostilities of the 1990s before heading south like so many Kashmiris to find steady work. He plied the beaches of south Goa as a tout, honing his English and sending wads of rupees to his parents. He returned to Kashmir two years ago. Business is still far from what he’d hoped. “People have this idea that in Kashmir there are militants on one side of the street and Indian troops on the other shooting at each other, and we’re caught in the middle, like this,” he said, raising his hands in mock fright. “That was the old Kashmir. Right now things are looking up.”

On a map, the Northeast links to the rest of India by narrow 21-kilometer-wide skein of land informally known as the Chicken’s Neck. It expands into a wild landscape of steep hills, valleys, and mighty rivers—such as the Brahmaputra, which appeared frozen in the predawn gloom as we sped northward out of Guwahati, the capital of Assam. The region is home to some 500 ethnic groups that compete with one another for a share of natural spoils that include 1.3 billion tons in proven oil reserves.

I’d been invited to meet with leaders of the National Democratic Front of Bodoland (NDFB), one of a dozen or so groups in Assam fighting to carve out an independent ethnic homeland. For the past three years they have observed a cease-fire with the Indian government, which restricts them to three designated camps around the state where they are allowed to retain their arms until a political deal is brokered. My personal knowledge of the NDFB, their methods and reputation, was limited to little more than this. So when we pulled into one of the camps, the foothills of southeastern Bhutan thrusting beyond the tree line, it was heartening to see the militants making the most of peacetime.

Guns and fatigues were nowhere to be found. Instead, four rebels in jeans and knockoff Diesel T-shirts were playing a heated match of carrom at a makeshift reception center, daubing their trigger fingers with talcum powder. Outside, others played volleyball, and when the ball ran astray they carefully tiptoed over the manicured bed of posies that abutted the court. A few industrious ones chopped wood or jogged around the barracks. They wore blue tracksuits with stripes down the sleeves that implied Adidas sponsorship. More like summer camp, I thought.

A young man handed me a media kit that included the Bodo (pronounced “bo-ro”) constitution and manifesto, promotional videos, and the pamphlet NDFB: A Brief History. The Bodo motto, “Let us die for Bodo nation, but let not Bodo nation die for us,” was written at the bottom in crimson letters.

“Our history is there,” said Brahman Baglary, jabbing his finger at the pamphlet, “the one you will never find in Indian history books.” Cloaked in a Nehru jacket whose collar accented his strong jawline and wide Mongoloid cheekbones, Brahman serves as “peace and rights officer” and spoke with a booming rhetoric usually reserved for a mass audience. He explained that the Bodo, whose ancestors are believed to have migrated from the steppe of northwestern China, were a royal dynasty that predated Aryans in present-day India. The British colonized them in the early 1800s, staying on until partition in 1947. Assam’s more prominent ethnic groups were poised to gain independence when the Indian government intervened and annexed the region, giving rise to various insurgent groups like the NDFB, the United Liberation Front of Asom (ULFA), and the Nationalist Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN), which have sustained a low-intensity war against the state since the mid-1980s, costing some 20,000 lives. “As you know, indigenous people are not to be separated from our land rights,” he said. “These were snatched by the Indian government.”

The NDFB was founded in Assam in 1986, according to the Bodo constitution, to secure a sovereign Bodoland “free of colonialist exploitation, oppression, and domination.” The Bodos are a primitive tribe that account for about 10 percent of the state’s 26 million people. While the Bodo people traditionally use a script called Devanagari and practice Hinduism, the NDFP ranks are mainly Christians who prefer Roman script. Home Ministry reports, though prone to exaggeration, blame the group for hundreds of killings, bombings, and kidnappings since the armed campaign began in northwest Assam, where porous borders have for years allowed them into Bhutan and Myanmar. The Bodos counter they have defended their identity and resources from a plundering central government that has allowed non-Bodo migrants, mainly Bangladeshis, to flood their homeland. Fighting was sporadic until December 2003, when the Bhutan military waged an offensive—with India’s backing—called Operation All Clear, which succeeded in razing twelve NDFB and thirteen ULFA bases inside their borders. Several hundred militants were killed, dealing a mortal blow to the NDFB, whose ranks inside Assam today are no more than 700. The cease-fire agreement was signed in New Delhi fifteen months later.

The NDFB camp I visited lies at the fringe of Udalguri, a nondescript town with a T junction off the state railroad line. My escort, Raakesh Boro, and I strolled in the pale light. We passed bored reserve police officers who wore body armor and carried SLR rifles. The streets were deserted, storefronts locked up. The week before, a homemade bomb was tossed into a neighboring village market, injuring eleven Bengali shopkeepers. The shopkeepers union called a strike, which no one dared contradict. Raakesh quipped that “in Assam, profit always comes a distant second to petty”—read ethnic—“politics.”

At the center of town stands a bronze statue of a member of the All Bodo Students Union raising a fist to the sky. Raakesh told me he’d agitated as a student union leader until activism turned to militancy with the NDFB. It was hard to picture Raakesh, who was short and stout, generous with his easy smile, being angry with anyone for long. I asked him why he’d decided not to pick up a gun for the NDFB, as many of his closest friends had done. “Even then, I saw that the might of India was too much,” he said. “Politics is a long, slow process, but I am still here. Most of us are happy with the cease-fire.”

Raakesh has since lived on the sidelines, devoted to growing three varieties of Assam’s best-known export on a terraced 77-acre estate a stone’s throw from Bhutan. Today Assam accounts for 55 percent of India’s total tea production, he boasted, adding that the potential is growing. “Organic tea is big right now,” he said, smiling. “Especially where you come from.”

Ajai Sahni works in white plaster bungalow on a shaded lane less than a mile from India’s parliament in New Delhi. A respected academic once described him to me as “state-ist,” a view reinforced by the closeness of his office to the corridors of power and the armed security guards at the front gate. His appearance, too, is refined in the way of a veteran government official: slicked-back hair, wire-rimmed glasses, salt-and-pepper mustache neatly trimmed, a fine command of idiomatic English. His view of India is messy by comparison.

Over the course of several interviews at his office, he punctured the “dangerous half-truth” of India Shining, a Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) advertising campaign that sought to position the country at the fulcrum of a global power shift, ballasted by four billionaires in the Forbes’ top-ten list, highly profitable call-centers, Bollywood, and world-beating factories whose latest feat is a 100,000-rupee (US $2,500) mass-production car. Meanwhile, 80 percent of Indians—some 836 million people—live on less than 50¢ a day. Water is becoming scarcer. Thousands of debt-ridden farmers are killing themselves. Child malnutrition figures are equivalent to most countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Despite an economy that grows 9 percent each year, India dropped two places, from 126 to 128, on the latest UN human development index of 177 countries.

The other India is not always hidden from view. In Mumbai and Delhi, staggering poverty rubs elbows with a well-heeled middle class, as millions have abandoned village life in search of better prospects. Urban slums have bloated into cities within cities. By 2020, the urban population is expected to grow to 40 percent of India’s total population, placing tremendous pressure on infrastructure that is already at the brink of collapse. The masses, however, will remain stranded in the interior, Sahni said, “where it’s not only a different century, but a different world.” It is there that gross neglect and distress conspire to breed lawlessness.

Several years ago, Sahni helped establish the Institute for Conflict Management, the first agency of its kind created to assess security trends and fault lines throughout India and South Asia. At the time there was no comprehensive source for reliable information on terrorist or rebel outfits. Establishment reports were dry and rife with guesswork, while the mainstream press shied away from providing on-the-ground reporting in the hinterlands—a shortcoming he still bemoans. In addition to the institute, he set up a South Asia terrorism database: a public stockpile of security data that features updated media reports and in-house analyses, many of which he writes himself. Although coverage spans from Pakistan to Bangladesh, three specific domestic threats—Islamist separatism in Kashmir, ethnic fundamentalism in the Northeast, and leftist extremism in the Hindu heartland—hold his focus.

At present, these three threats account for armed conflict in 20 of 28 Indian states. The common thread, Sahni says, is that all three are in “irreducible conflict with [India’s] liberal democratic tradition in general and modernization in particular.” For all its faults, he notes, India has a thriving democracy that has held the country intact thanks to the participation of rich and poor, Hindu and Muslim, upper caste and untouchable. In the 2004 general elections, for instance, nearly 60 percent of eligible citizens voted. A large portion belonged to vote banks that have given some underclass politicians a stranglehold in certain areas. This dynamism has also consolidated India’s position, bang in the middle of a bad neighborhood, where trouble looms at every border.

The transnational threat of radical Islam will not disappear any time soon, as recent bombings in Mumbai, Bangalore, and Hyderabad attest. According to government figures, at least 95 foreign-backed terrorist cells were broken up across the country between January 2004 and February 2008. But a sharp decline in Islamist violence has registered in Kashmir, of all places—a change Sahni credits to instability across the border. Without military support, Pakistan-based jihadis are having a much harder time crossing over than before; aggressive factions such as the Hizb-ul-Mujahideen, which relied on cadres inside India, are floundering. In Sahni’s view, the unrest in Pakistan has made Pakistan less appealing to Kashmiris, who have grown tired of violence and now look to the ballot to bring change, as do the 150 million Muslims in the rest of India. Improved security has allowed state governments to serve full terms, a rarity next door. “Kashmiris are looking at the reality of all that is happening there. Thinking it’s too much of a bloody mess, we’re better off over here.”

Security in the Northeast has also shown some improvement, though under-policed international borders hamper progress. This is especially true in Assam and Manipur, Sahni said, where a mixture of state mismanagement “at scales you cannot imagine” and external support has given steady oxygen to separatist factions. ULFA, the mother insurgency of the region which wants an independent Assamese homeland, receives financial and arms backing from Bangladeshi intelligence (with an extra hand from Pakistan’s ISI), which the ULFA uses as a rear base. In the lawless reaches it occupies, the group extorts from businesses ranging from tea to electricity, to fund hired guns that operate with impunity. The original grievance that spawned the group, the inflow of non-Assamese settlers, has been abandoned out of necessity and greed. “There’s no logic left in their movement,” he said. “It’s basically a business. This is the case for most groups operating in the region.”

Criminality will persist so long as there is a deficit of law and order in the Northeast. But pluralism in the region may well render competing groups obsolete. “The very nature of movements rooted in ethnic identity has made it impossible for them to go beyond their demographics,” Sahni continued, “so these movements are circumscribed and, inevitably, will destroy themselves.” Or adapt. Another Bodo separatist outfit, the Bodo Liberation Tigers, renounced violence in 2003 and entered politics. Last November, sixty-four ULFA fighters formally surrendered to the army. “These movements know they cannot really stand against the Indian state, which has enduring strengths.”

And enduring weaknesses.

“The Islamist is dying, the ethnic [separatist] is dying,” Sahni warned, “but they may be replaced by the Maoist.” He spoke of a rift in the Indian security establishment between those who are looking at the Maoist movement as it stands today, and those who see its potential. “The Home Minister has more transient political objectives in mind. He says the Naxal threat is fading . . . If that’s the case,” Sahni asked, “then why is the movement spreading?” Prime Minister Singh, on the other hand, is one of the few who recognizes the Maoists are “building up to a confrontation that is based on the exploitation of every single vulnerability and fault line within the Indian system, which they are already doing with great rigor and,” Sahni hesitated, “almost with genius.”

The Maoists consolidated in 1967 in response to the domination of upper-caste landowners in agricultural states such as Andhra Pradesh and Bihar, where lower-caste and tribal laborers faced abhorrent working conditions. At the time, activities were both legitimate, in the form of labor unions, and illicit, as when members would ransack a police station for firearms. For the next twenty years they operated on the margins of Indian politics, until a shift in the 1990s that saw the group ramp up their armed struggle against the state. The two largest factions, the People’s War Group and the Maoist Communist Centre, merged in late 2004 to form the Communist Party of India (Maoist). After a forceful state crackdown in Andhra Pradesh, their longtime bastion in the south, the Maoists found traction among downtrodden communities in the heartland—and with none more than the tribals.

Of India’s 80 million tribals, about 15 million live in the Northeast; the rest are concentrated in the center of the country, short-changed of security and basic services. An estimated 23 percent are literate, and as many as half live under the poverty line. The fertile swaths they inhabit are both a gift and a curse. As India’s economic boom kicks into overdrive, the government is abetting companies that extract timber and minerals from resource-rich areas, often muscling tribals off their ancestral lands in the process. According to one independent study, a tribal is five times as likely as a nontribal to have his property seized by the state.

In January, I spent a week in western Orissa state with the Dongria Kond tribespeople. Cannibals until the late nineteenth century, they live outside of Indian history—except for once a week when they travel on foot as many as ten miles to sell tendu leaves (used to roll bidi cigarettes) and palm wine at the nearest town market. For the past four years they’ve been involved in fierce legal battle with a UK-based company that wants to mine bauxite ore from sacred hills. In a scenario typical of many others playing out around India, Vedanta Resources built a refinery at the base of Niyamgiri Mountain without approval, expecting ex post facto support from the state. The Dongria, backed by a small army of activists, fought all the way to the Supreme Court in Delhi. The bench made a surprise ruling in their favor. In doing so, they also spelled out a loophole that may one day allow the company to break ground. Once again, the Dongria are bracing for a fight. “If anyone comes to take our Niyamgiri we will fight them with axes and shoot them with arrows,” tribal farmer Bari Pidikaka, told me, raising his battle-ax, “so these people can understand how the Dongria Kond are strong and love these hills.”

Lower-caste groups face the same assault. The Communist Party of India (Marxist)—which since independence has dominated West Bengal politics on a platform of social justice—decided last spring to allow an Indonesia-based company to set up a chemical hub, and that meant converting 10,000 acres of farmland into a Chinese-style Special Economic Zone (SEZ). Villagers resisted for months, until the state government dispatched 4,000 armed police and party thugs to evict them. In the ensuing violence at least 11 people were killed and 70 wounded. Nine more people died when protests flared again in November. The Marxists have accused the Maoists of stoking tensions, which still boil in the region, and elsewhere, as similar projects are imposed. Indian trade minister Kamal Nath, for his part, recently defended SEZs—now totaling 453 across 19 states—for generating billions in exports, “notwithstanding the skepticism expressed by a few persons.”

The backlash at Nandigram and Niyamgiri illustrates how development in India often favors a select few at the expense of many, widening social rifts the Maoists are keen to exploit. “We, the Maoists, are confronted with the great task of providing revolutionary leadership to over a billion people, at a time when the entire country is being transformed into a neo-colony, when the country is being sold away to the imperialists and the big business in the name of SEZs, when millions upon millions of people are being displaced by so-called development projects, when workers, peasants, employees, students, sections of the intelligentsia, [untouchables], women, [tribals], religious minorities, and others are seething with revolt,” proclaimed the Community Party of India’s general secretary, Muppala Lakshmana Rao who operates under the nom de guerre Ganapathy. “We shall be at the forefront of every people’s movement.”

To pinpoint levels of discontent before mobilizing, the party conducts in-depth social and economic surveys. In protected urban areas, it wages an overground campaign to attract disaffected members of the middle class. Slick new websites can now be found on the internet, and volunteers canvass neighborhoods. Inflation, unemployment, the high costs of education and health care are but a sampling of the issues “the party has drawn up plans for, to mobilize the middle class,” according to the elusive leader. And the two-front strategy appears to be bearing fruit; the influx of Maoist sympathizers into Delhi has been so great that an anti-Naxalite police wing is being created. To Ganapathy, all of this is part of a “protracted” war, in which flexibility—and patience—means growth. But he maintains that a cornerstone must first be carved out of “the more backward areas in central and eastern India,” to anchor the coming offensive.

On the government side, the natural antidote would be to scattershot development to areas where the Maoists are gaining traction. The problem is one of scale. By 2050, India will likely have a population bigger than China’s; some 900 million will be in rural India, of which just a fraction will have steady employment. “There is all this talk of development as a solution,” Sahni exclaimed. “But what do we offer all these people? What is the developmental model that will bring them enough prosperity to wean them from violence? People talk of development like it’s a dish that can be ordered—a plate of development, and a garnishing of justice, please.”

So what then?

“Security! You must first re-possess the area. Otherwise there is no development. The areas to which the Maoists have moved in to fight are in almost complete administrative neglect . . . You couldn’t even keep cattle there.”

Of the twenty-two official camps throughout Chhattisgarh created to house people displaced by the government conflict with Maoists, Dornapal is the largest. Row upon row of mud-and-sheet-metal barracks shelter more than 17,000 people, though there are surely many more still in hiding. My interpreter, Chandan, and I were met by Mukesh, a self-proclaimed “development officer” who said he had to escort us through the camp because we were “special guests.” We had no choice. The government was giving out plenty of food, he beamed, and schools were full.

Near one of the camp entrances, a group of tribal women in torn saris wielded pickaxes and shovels to level a dirt pathway. They were part of a state rehabilitation program that provides guaranteed work at the rate of 100 rupees an hour. It was impossible to confirm if they’d been paid; no one wanted to speak in front of our escort. In a thatched-roof hut close by, Lachi Betti, a mother of four, was busy distilling mawa berries into a homemade hooch popular among camp residents. She sold it in used plastic soda bottles. Men did the drinking, squatting in the shade and waiting for nothing in particular.

A gang of special police officers approached. Mukesh said two of them are ex‑Naxals who’d taken advantage of a government amnesty and now fought their former comrades. Saryam Boja, twenty-two, said he was beaten into serving as a village lookout for the Naxalites before moving up to rig explosives. Five years later, he realized that people supported the Naxals “just out of fear.” So he turned himself in to police to be recast as an SPO, and he was bent on revenge. I read the slogan on his T-shirt, spread across his chest: NOBODY’S PERFECT, AND I’M NOT NOBODY. His friend, Chotu Barse, chimed in that the Naxalites had come to his village and abused his family for refusing to pay extortion money. “I decided I needed a gun to fight them, so I joined Salwa Judum,” the scrawny eighteen-year-old said.

Farther inside the camp warrens, naked children splashed in pools of fetid water. Trash heaps smoldered. Leathery elders lazed under tarps emblazoned with the logos of CARE International and UNHCR, the UN’s refugee agency. We stopped for a drink and a crowd of villagers quickly gathered around to investigate us. I was hoping to do the investigating, and asked a clutch of young men what they thought of Salwa Judum, camp life, the Naxalites. “We hate the Naxals here because they interfere,” said one man, as if reading from a script. He glanced at Mukesh for approval. “The government has given us roads and schools and tries to stop them.”

Finally, a voice in the crowd spoke from the heart. In a flurry of Gondi, the tribal dialect, farmer Kavashi Budhram said he was fed up with being stuck in the camp and wanted to return to his village, ten miles away, where he could work his family plot. “Salwa Judum people are coming into our villages and making problems for us. They say we must choose,” he said. “They are like the Naxals.” Mukesh was displeased, and cut him off in a harsh tone that softened into a sanitized explanation of the outburst. Time to move on, he said, finishing his drink. The straight story was not going to come from anyone at Dornapal.

Later that day, on a gravel track off the main highway to Dornapal, Captain Rajesh Pawar pointed to a tree about fifty yards from where we stood. “That’s where his legs were, hanging off those branches.” Last year three of his men were riding a tractor down the road to a forward base at Pullampalli village, which they had just reclaimed from the Naxalites. They drove over a Naxal mine, which killed them. A crater outline the size of a Volkswagen Beetle marked the spot. The area, while secure, was still by no means locked down. “If we don’t keep up our patrols, all this will be lost again,” he said, explaining that all vegetation had been clear-cut to prevent any future ambushes. Two miles down, the road stopped at Pullampalli, set on a hilltop plateau littered with concrete-block buildings allegedly destroyed by the rebels.

Captain Pawar led me around without comment, allowing me to make my own judgments. Unlike most of his men, Pawar was solid as a fullback. He’d earned their respect, having fought guerrilla-style in the bush for over four years, winning back eighteen square kilometers of turf one meter at a time. Yet he could only grumble over the lack of capable fighters and munitions, saying at least twice as many men were needed to secure his patch of Bastar. More importantly, he added, they must be trained to fight as the enemy fights: to be mobile and remain in the shadows. “This is guerrilla warfare. The Indian Army is not prepared for this.”

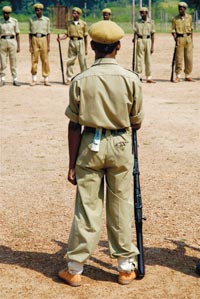

Rani Bodli is still fresh on everybody’s mind. The Bastar police camp was the scene of the Naxalite raid a year ago that left fifty-five security forces dead, nearly half of them SPOs. A part-time journalist in Dantewada showed me footage he’d shot the morning after: bodies were laid out in front of the lone barrack, many of the faces hacked or singed beyond recognition. Standing there, I tried to imagine how it must have been, hundreds of screaming rebels attacking from pitch-blackness. Now a new batch of SPOs played a game of cricket. Officer Sanjay Kanday of the Central Reserve Police Force told me guards kept a twenty-four-hour lookout on the forest from pillboxes on each corner of the perimeter. I walked inside one and was shocked when a boy not a day over fifteen turned around, lowered his rifle, and gave a shy smile.

-

- Teenage “special police officer” scans the forest around Rani Bodli camp, scene of a midnight Naxalite raid early last year that left 55 security forces dead, South Bastar region, Chhattisgarh state.

We drove on. Low-slung police bunkers ringed with razor wire dotted the road. More nervous boys with rifles. It was nearing the end of the weekly market day when we came to a grassy clearing. Off to the left a raucous hive of tribal men indicated the cockfights were still on. When they saw me walking over, they parted for me and closed again, sealing me into a ring that stank of sour sweat and cheap alcohol. Razors were strapped to the birds’ feet; they crashed into each other, edging the crowd toward frenzy with each flurry. Fists of dirty bills traded hands. I felt a tap on my shoulder; it was Chandan, my interpreter. “We go now,” he panted. “I forget to say that last week some Naxals attack here. They kill two SPO. Maybe come back.”

The consensus among journalists and aid officials in Bastar was that police had tenuous authority over towns, camps, and country roadways during the daytime. At night, it was accepted that the roadways were a toss-up, the forest off-limits. By now the sun was melting into the horizon, and between Dantewada and us lay many miles of uncertain darkness.

An eventful day then took a farcical turn. Just outside of town Chandan got a call: jailbreak at the Dantewada jail. Pots and pans were scattered all over the ground when we arrived. A generator hummed in the background while floodlights combed the night. A total of 299 prisoners had escaped en masse, including 105 described as “Naxal activists.” None had been found. Chandan told me the guards had been overpowered and beaten, but lived. How many were there? He shook his head. “Five.”

In his office the next day Rahul Sharma, the superintendent of police, told me, “The security scenario right now is pretty grim.” Sharma, in his first posting, was from Delhi. Bastar was hardly a plum assignment. In the previous eight months, he said, 137 of his officers had been killed. “We have a terrible shortage of manpower,” he continued; he was supposed to have 1,800 men but currently had 800. Some 6,000 “boys” have been recruited and are still training, he explained. The Greyhounds, a jungle commando unit that has had success against the Maoists in Andhra Pradesh, were being replicated in Chhattisgarh and other vulnerable states. The irony was that the Greyhounds’ maneuvers in AP basically pushed Maoists into Sharma’s backyard. “It will take time,” he said plaintively, “but we do expect some improvements once force levels increase.”

On the parade ground outside, several hundred green trainees marched to the orders of Sharma’s officers, who were frustrated. The trainees, wearing ill-fitting khaki uniforms and sneakers, fumbled with their rifles; some turned in the wrong direction when an officer called an about-face. It was a display that failed to inspire confidence.

The Assam government is based in Dispur, a leafy town on the Brahmaputra River about eight miles from the hustle and smoke of Guwahati. I met with a senior state intelligence officer who is normally not allowed to speak to journalists and so asked to remain anonymous. “Let me first say that the Northeast has always had many obstacles to stability,” he said serenely from behind his mahogany desk. “There are hundreds of ethic groups, open borders, rough terrain for policing.”

Today the government is spending millions to develop infrastructure as part of the Look East initiative designed to transform the region into a trade gateway to Southeast Asia, he said, inviting neighbors to explore timber, natural gas, and mineral resources. I mentioned government figures showing that outsiders were in greater danger of being targeted by nativist outfits. He attributed this to a creeping sense of desperation among militant outfits such as ULFA, who kill civilians to sow panic.

“Look at the statistics you speak of. Last year more than 450 civilians were killed in the [Northeast], compared to about 75 security personnel,” he said. “That should tell you that these people are afraid to fight our forces head-on. They target the weak instead . . . Eventually, all their support will dry up because of this.” He handed me a copy of the latest Assam Tribune. According to the headline, unknown rebels executed 14 Hindi-speaking migrant workers in nearby Manipur state. “Make no mistake, the majority of people in the Northeast today are not anti-Indian. People have accepted India as their country.”

-

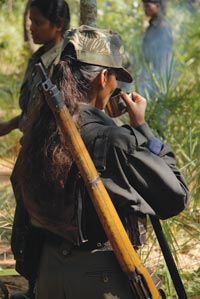

- NDFB 2nd Lt. Pwilao Mushahary with Boro separatist fighters at cease-fire camp, Udalguri, Assam state.

Outside the wire of the NDFB cease-fire camp, Prafulla Basumatari admitted that he and most of his neighbors would settle for a Bodo state within the Indian republic if it meant calm. “Before the cease-fire, this area had no peace at all,” said Prafulla, a school headmaster, whose adobe home sits within view of the barracks. “All the time there was a fear in the minds of people—when and what would happen, nobody knew.” Several of his students had joined the NDFB in the bush, never to come back. As fighting intensified, the Bodo community pressured the NDFB to come forward for peace talks, which they did only after heavy losses. I recalled an earlier interview with N. G. Mahanta, a political analyst in Guwahati, who told me conflict fatigue is a time-tested strategy of the Indian government in the Northeast. “If you fight the Indian state for ten, fifteen, twenty years,” he said, “after that you don’t believe you can beat the Indian state.”

Back at the NDFB camp, Second Lieutenant Pwilao Mushahary tried to convince me otherwise. The day before, when I first met him, he greeted me warmly at the gate; he wore a Bahama shirt and sandals. Since then four NDFB cadres had been shot dead at another cease-fire camp, Kokrajhar, at the northern banks of the Brahmaputra. Police called them fratricidal killings, blaming “unknown miscreants” associated with a breakaway Bodo faction. Mushahary had switched to his olive-drab jungle attire: there was a 9-mm pistol tucked under his belt. He was flanked by ten militants bristling with automatic weapons.

After three years, no government envoys had come forward to push the peace process forward, he claimed. “The response from the Indian government has been completely insincere. We do not have peace. Instead they are killing our cadres. If this is the attitude of the Indian government,” he said, placing his right hand on the pistol, “then the NDFB is ever-ready to go back to the jungle and renew our struggle.”

Such saber-rattling seemed at odds with the prevailing calm in Bodoland. As far as I could tell, the NDFB was not under siege by the Indian government. Aside from a few patrolmen in Udalguri, the state’s hand was almost invisible in Bodo territory. On the drive back to Guwahati, we passed a single army outpost of the “Red Devil” battalion. It was Holi, the festival of color, and the troops were running amok in the compound, throwing fistfuls of bright pink powder at one another.

Take a walk in central Srinagar, the heart of Jammu and Kashmir, and you will see where India’s security forces are tied down. Every block, reserve police stand watch as though on twenty-four-hour high alert. Their inescapable presence follows you out of the summer capital into the valley, with its endless chinar trees and bogs. Here, also, the men in green pace back and forth, sucking down cigarettes against the cold.

Overall, about 700,000 troops are stationed in Kashmir, or one for nearly every ten Kashmiris. Their bunkers used to be made of sandbags, residents told me, but now the sand has hardened into concrete, like permanent homes. “What Britain did to India, India is doing to us,” said Falak Mahseen, a 22-year-old medical student. Her political awareness was sharp—in this she resembled most young Kashmiris I met. She told me that almost 90 percent of Kashmiris still want independence, so the state is using the unending threat of Islamist violence as an excuse to justify an occupation. “We want peace here, but we also want our own state. Peace or no peace, this desire will never change.”

I asked Kashmir’s police superintendent, S. M. Sahai, what he could say to young Kashmiris who feel dogged by security forces at every turn. If they don’t see a reduction as the years wear on, might some of them vent their frustrations through violence? “As the situation has improved, the overt presence of forces has been reduced,” he said, “maybe not to the extent that people would like. But they have been brought down, and we will bring it down more depending on how the situation emerges.” But if there is clear evidence that Islamist militancy has plummeted—it’s estimated that 450 fighters remain in Kashmir—why do government force levels remain in such lopsided numbers? “The Pakistan factor is still there,” he said, rejecting the idea that improvements were a function of Pakistan’s internal preoccupations. Sahai argued that the “renewed vigor” of Indian forces was behind the turnaround, boasting that 86 percent of last year’s enemy engagements were initiated by state forces. But to many Kashmiris, this indicates the government is looking for trouble.

“We were expecting that [the Indian government] would have already withdrawn their forces from civilian populated areas, but they have not done it yet,” said Yasin Malik, Chairman of the Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF). “That is the reason why the Kashmiri people have a lot of questions about this peace process.” When I first met Malik, I didn’t like him. I had walked into a headquarters full of grave men reading newspapers—ex-militants to a man, I later learned—and no one bothered to look up. The silent treatment continued as I took a seat on the floor. Finally I asked where Malik was, heard a mumble, and realized he was right next to me.

What struck me then as arrogance may have been fatigue; he’d just completed a 114-day tour of hundreds of villages to gauge grassroots support and “spread the message of brotherhood,” in a bid to become a popular spokesman. On my way back to my hotel, I passed posters of him being cheered by adoring crowds. In some part of Kashmir, Malik is revered as a freedom fighter, the epitome of the Kashmiri struggle.

Malik’s days as a student activist were cut short when he was thrown in jail, at eighteen, for printing stickers calling for an independent Kashmir. Several imprisonments later, he’d lost hearing in one ear due to beatings, and blood poisoning had damaged a heart valve. “In the land of Mahatma, I could find no Mahatma present,” he said in his slow, brooding tone. “At the time, there was no space for a nonviolent movement, so I took up the gun.”

As head of the JKLF, the first militant group to call for full independence, Malik waged a bitter guerrilla war. Then, in 1996, he declared a unilateral cease-fire, renouncing violence. Scores of prison stints gave him time to read, he said, and Nelson Mandela became his hero. Although he claims India has killed more than 600 of his colleagues since the cease-fire, he affirms his commitment to dialogue. But he laments the psychological backlash if Kashmiris aren’t given more breathing space. “Over the last two years the Indian government has had such an opportunity, as no other government has had since 1947. If the people of Kashmir lose hope in dialogue, then definitely, they will go back to where I started.”

After a series of false starts, we set off to meet the Maoists. Mr. Pille had introduced me to Arvind, a video stringer for state news agency who said he had met with the rebels on two occasions. Along with Chandan, my interpreter, I hung on as Arvind’s 150‑cc Hero Honda tore down back roads to avoid the dawn police patrols. We passed Hindu shrines with offerings of carnations and cracked coconut. At the Indravati River crossing, fifty rupees paid for a dugout canoe ride into rebel territory. Territory not seized by force, Chandan said, but abandoned by the state. The ruins of a government-built schoolhouse, smashed by the Maoists, lay next to the lodge where we spent the night and from which we sent our message.

Three tribal militiamen loyal to the Maoists, known as sangam, came down the next day to escort us. Barefoot with a bow and quiver of arrows slung over his shoulder, the eldest one informed us that once they took us to their village, we left when they decided. We shrugged in agreement. For the next seven hours we moved at a calf-busting clip, stopping just twice: first to share a giant cucumber, again when a bear was spotted on a bluff above the trail. We pressed on past roaring cascades, through dirt-poor hamlets whose inhabitants had never laid eyes on a foreigner. Some stared in wonder, others ran from us.

It was dark by the time we reached their village. At Chandan’s request, a rooster was killed with the quill of one of its own feathers, plucked, and boiled. The village leader came to meet us. Instead of shaking hands he gazed at us with a kind of dumb suspicion. We presented our ID cards and equipment as evidence of our profession. It was clear he could not read. He told us that the last teacher had fled the village a year ago. Then he announced that he would meet us at first light with “a decision.”

Two hours after sunrise, we came to understand that his decision might involve our lives.

Nothing stirred around us. The village leader never showed up. With a lump in his throat Chandan started singing. Arvind tapped his feet. The heavy silence was broken by the ring of alarm gongs on all sides. We watched as every able-bodied man in the village streamed up the hillside across the ravine, carrying machetes, hoes, axes, and other homemade farm tools. For what reason, none of us wanted to guess.

“Ram, Ram, O Ram,” Chandan’s songs had turned into whispered prayers. In a final effort at hedging our fate, he instructed me to invoke my God. I said I would, double-knotted my boots, eyed a hefty stick, and prepared for the worst. The village men reappeared, streaming single file down the path they’d earlier climbed. Weapons in hand.

“Back of the beyond,” a friend had joked before my first trip to Bastar, bugging his eyeballs for effect. “It’s savage where you’re going.” At the time, the comment rang of the casual disdain many youngish urbanites have for the India they like to call “backward,” a swamp of ignorance most would prefer not to see or acknowledge. I thought I knew better. Seated on a tree stump two days’ trek from the nearest telephone, I braced myself for the sharp end of the unknown.

“We apologize for the treatment you received earlier today,” said Rajman, a Maoist officer, moments after he strode from the darkness. He handed me a pack of sugar cookies. I was told later that he’d traveled four hours on foot from his base to personally welcome us and to apologize for our unease. “The people’s army is happy to have you as our honored guests.”

To our eternal relief, six Maoists had arrived in the morning to take us to a camp deeper in the mountains. They were led by Comrade Sunil, who insisted we have some black tea before departing. After a four-hour hike inland, we made camp next to a vegetable garden tended by a friendly tribal family, who welcomed our group with a mashed-corn-and-rice drink served in hollowed gourds. Their faces bore none of the resignation common to the refugees I’d met in the roadside camps. Ram, the patriarch, said he didn’t mind the Maoists so long as their war never touched his home. “We don’t want to fight or leave our homes,” he said. “We only want to live like we always have, a natural life.”

Women cadres began coordinating the evening meal with some of the younger male recruits. Comrade Sunil leaned against a haystack and told me he’d joined the cause a couple years ago after his older brother was killed by SPOs. Exceedingly polite, Sunil took great pride in his appearance: his camouflage shirt was crisply pressed and tucked in, his brown plastic Bata loafers spotless. He admitted he’d never seen combat, but he swore with the earnestness of a schoolboy that he was ready to fight to the death. “I am prepared to stay out here and fight like this for the rest of my life,” he said, to the nod of a dozen other fighters. “And so are all the comrades of the People’s Liberation Guerrilla Army.”

A dinner of curried vegetables and rice was served. The portions given to Chandan, Arvind, and me were twice as large as the cadres’, and no one touched their food until we started. Everybody ate in comfortable silence until the Maoist officer Rajman materialized from the darkness. The cadres rose to greet him with a round of “Lal Salam” (meaning “red salute”). The fire at his back made it impossible to see his face, adding to the drama. We talked late into the night, going over the itinerary and the terms of our visit; Rajman said no faces could be caught on film or tape. The upshot was that a subdivisional commander would likely pay us an early morning visit for a rare interview.

At first light the cadres started their daily routine. The men and women broke into two groups and headed to separate stretches of a nearby stream, where they washed their hair and feet, brushed their teeth vigorously, and combed their hair. A transistor radio was tuned to the BBC World Service. Foaming toothpaste at the mouth, Sunil said that living in the bush was no excuse for bad hygiene; if anything, his superiors had told him, it demanded an extra effort.

An echo of Lal Salams signaled the arrival of the commander, Pandu. Like Rajman, he looked like a hardened fighter, and he proved to be very articulate. He distributed some Communist tracts to the cadres before sitting on a tarp by the water’s edge. Our interview lasted about an hour, during which he touted the importance “liberating” areas like Bastar. These would serve as bases for expansion, until the zones were interconnected and reached all the way to urban centers, a strategy I’d come to understand. “The people’s revolution is still in the early stages,” he said. “Time is on our side.”

Under the present circumstances, it was easy to dismiss this as wishful thinking. The wilds of Bastar are a long way from the capital. And for all their enthusiasm, most of Pandu’s foot soldiers didn’t even know who Marx and Lenin were. A handful had heard of Mao, but they couldn’t say for sure where he was from. Then again, humble beginnings in Russia and China sparked dark horse revolutions that changed history.

An army of fire ants had given me fits since the interview began. I pointed out that a column of them was climbing up Pandu’s leg. “They are our friends,” Pandu said. “We must share the forest.”

Jason Motlagh traveled to India on a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting. The Center’s journalism on internal conflicts within emerging global powers is funded by the Stanley Foundation. For more information visit pulitzercenter.org.