The last US service member to leave Afghanistan’s soil after nearly twenty years of war did so just a minute shy of the midnight deadline on August 30. The gruesome chaos that unfolded in the days leading up to that departure, after the hasty withdrawal of US and NATO troops unleashed a rapid sweep of Taliban forces that recaptured the country in less than ten days, left many of us wondering what all the sacrifices of a twenty-year war had been for. The quickness with which the Taliban had regained control of the country and the deadly havoc at Kabul’s airport in those final days—culminating in an attack by suicide bomber that killed thirteen American service members along with dozens of Afghans seeking to escape—created an eerily disorienting sense that Afghanistan’s democratic infrastructure had been an illusion. Blood and sweat were invested in that cause, and a generation grew up under what it seemed to promise, despite the government’s rampant corruption and dysfunction. But it didn’t take long for a cold truth to seep into the larger conversation of how this had happened. Even before the last C-17 took off, soldiers and reporters alike were asking: What did we expect?

With the Taliban back in power, and ISIS-K launching attacks at will, Afghan citizens are in real danger, every day. The country’s journalists, activists, scholars, along with everyday citizens who assisted the US and its allies—and Afghan girls and women especially—are at the mercy of a regime that professes to have matured in its practice of governing but fools no one about its proclivity for violence and oppression.

The Taliban’s victory marks a closure that asks for deep reflection, looking honestly and intently at what has unfolded in the twenty years since the George W. Bush administration launched Operation Enduring Freedom with the purpose of destroying al-Qaeda. If for no other reason, looking back helps us take some measure of that mission and what followed. In the interest of creating a resource for this reflection, the editors have assembled an online archive of VQR’s coverage of Afghanistan, from our reporting to photo essays to social-media nonfiction dispatches. Readers can find the archive by visiting our homepage or by going directly to vqronline.org/afghanistan.

For more than a decade, this magazine has devoted considerable coverage to the war, its motives and costs and consequences both abroad as well as here at home. The approaches range from war reporting to more essayistic profiles and narratives; stories of soldiers wrestling with trauma; of Afghan refugees seeking safe harbor in Europe; of refugees who, having been rejected for asylum, find themselves returning to a home country they barely know.

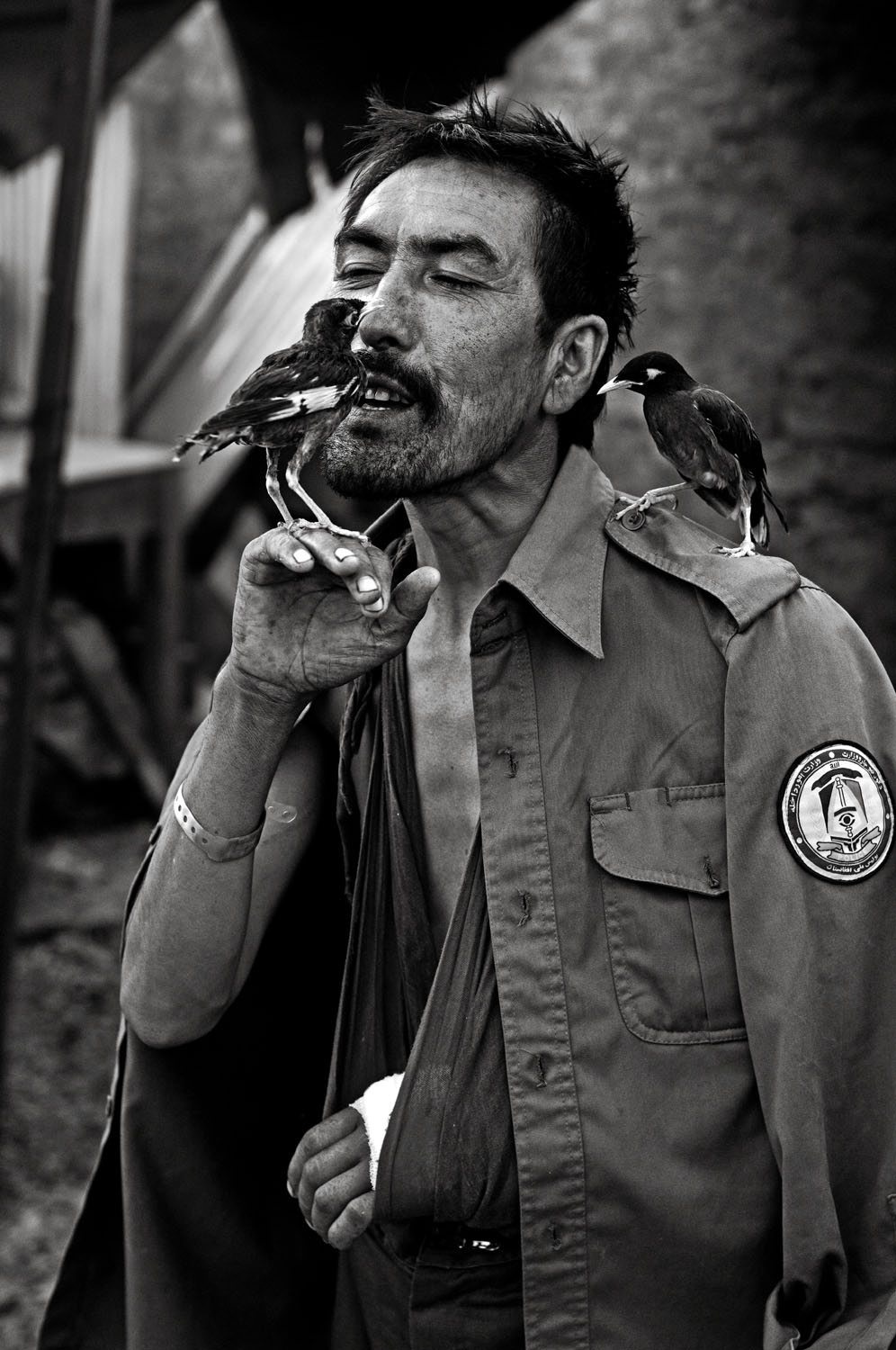

In some ways, given the Taliban’s presence in them, these pieces might be read as an archive of a notorious enemy. But they are also, clearly, testimonials of resilience and solidarity—that and more, something closer to heartbreak or madness, since many of us—soldiers, journalists, photographers, readers, Afghans and Americans alike—sensed that the mission itself had become vague while being no less deadly, that the worst lessons of military history were coming back around, and would be just as bitter.

It is sober reading, to be sure, but important for the depth of understanding it offers on what was lost, what it cost, and what’s now at stake. It’s also true that much of this perspective is delivered by a particular kind of voice, which is arguably a reflection of an editorial sensibility as well as the realities of journalism at the time these pieces were published. These qualities evolve as a magazine evolves, but at the heart of this archive, in all its depth and variety, is a pursuit of truth and clarity of purpose. War reporting is, at its heart, a heroic attempt at holding powers accountable. That perspective is as important now as it ever was in order to understand a war that will perplex us for generations to come, launched in a country whose people we sought to liberate, to understand, who we’ve harassed, who we’ve rescued, who we’ve tortured—with whom we have had such a complicated historical connection.

It should be noted, too, that many of these stories would have been impossible to report without the help of Afghans on the ground—fixers, drivers, and translators especially, many of whom are still struggling to find a way out of the country. Some made it as far the airport, only to be beaten back by Taliban forces guarding the gate. Their lives and the lives of their families hang in the balance.

One would be hard-pressed to come up with a gesture, however grand, that rises to the occasion of their commitment to helping get the story told. As veteran VQR reporter J. Malcolm Garcia put it, that commitment often transcended the nuts and bolts of reporting a story. “More important than all the information they helped you get, you formed a relationship,” he told me, during the agonizing last days of the evacuation. “You’re in a country where you don’t speak the language, you don’t know anybody, you look different. Without them, you were just kind of walking around muttering to yourself. If you didn’t have them, you didn’t have anyone to talk to, no one to eat with. You had nothing. So the passion journalists have shown in trying to get these guys out has less to do with the work, in my opinion, than the fact that these guys had become family. And we should remember that they took great risk being seen with you as the Taliban gained ground. We reaped the benefits while they now face retribution.”

Taking time to read the work they helped construct seems like a small gesture of appreciation—or perhaps it’s the most meaningful one, however far it falls short of their own bravery.

— Paul Reyes