My bounty is as boundless as the sea,

My love as deep; the more I give to thee,

The more I have, for both are infinite.

-Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet

In 1768, Benjamin Franklin, then postmaster general of England’s colonies in America, was presented with a mystery: why were British packet ships sailing from Falmouth, England, to New York regularly taking two weeks longer to reach their destination than merchant vessels traveling from London to Rhode Island? Franklin had already noted, on his own voyages across the Atlantic, that trips to England were much swifter than trips to the colonies. He theorized that vessels “partaking of the diurnal motion of the earth” might move faster, but the rotation of the globe couldn’t explain the discrepancy between ships bound for two points along the American coast.

For help, Franklin turned to his cousin Timothy Folger. Folger had spent his boyhood on Nantucket Island and had worked aboard whaling vessels much of his life. He told Franklin that whalers knew of a great “river in the ocean” that originated in the Gulf of Florida. Franklin later wrote:

We are well acquainted with that stream, says he, because in our pursuit of whales, which keep near the sides of it, but are not to be met with in it, we run down along the sides, and frequently cross it to change our side: and in crossing it have sometimes met and spoke with those packets, who were in the middle of it, and stemming it. We have informed them that they were stemming a current, that was against them to the value of three miles an hour; and advised them to cross it and get out of it; but they were too wise to be counselled by simple American fishermen.

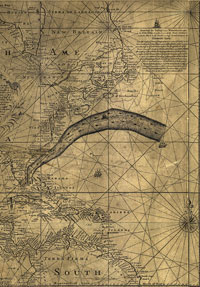

Folger drew up a simple map of the Gulf Stream’s course, which Franklin refined and had printed and distributed to British packet captains. Some have argued that with this, the first scientific investigation into the workings of the Atlantic, the wide oceans began to shrink-becoming increasingly dominable and knowable places. (Indeed, Franklin’s grandnephew John Williams, Jr., went on to publish Thermometrical Navigation in 1799, and one of Franklin’s great-grandsons, Alexander Dallas Bache, undertook the first full study of the Gulf Stream in 1845.) Franklin’s map, however, was largely ignored in his lifetime, perhaps because, as Folger posited, British captains trained in the Royal Navy were loathe to admit that colonial whalers might know more than they did about the ocean’s current.

To this day, a divide exists between the scientific experts who study our oceans, rivers, and lakes and the fishermen who regularly ply these waters in search of the day’s catch. It may be lingering arrogance of class and culture, as Franklin saw in his era, or it may be that the circles of scientists and fishermen have too rarely intersected-and when they have it has often been in a spirit of conflict over how best to manage precious natural resources. It may also be that scientists, even after centuries of study, are still often baffled and humbled by the limits of our knowledge-especially where deep-sea ecology is concerned. Near the end of his life, Sir Isaac Newton, disappointed by the vast expanse of still-unattained learning, is said to have lamented, “I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the sea-shore, and diverting myself in now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me.” The seas have always served as emblem of our ignorance, and our increased understanding of the oceans has only deepened their mysteries. The more we delve, the more the earth’s dark waters seem limitless and infinitely varied.

In recent years, however, scientists have begun to worry about the fate of our fisheries. As Donovan Webster notes in this issue, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization now lists two-thirds of all fish as fully exploited, over-exploited, or depleted. Increasing numbers of fishermen worldwide are finding it harder to survive. Readers of our Winter 2010 special issue on North Africa, for example, may recall that our writers reported how international trawler ships, unchallenged by any coast guard, had overfished the Gulf of Aden turning many Somali fishermen toward piracy, the West Coast of Africa allowing the drug trade to take hold there, and the Mediterranean creating an influx of refugees into Malta and deeper parts of Europe. The cost of overfishing is not only ecological; it is societal.

This issue sets out to see if there is anything to be done about this trend, to see whether we might be able to use our improved knowledge of our oceans and waterways to save them, rather than pillage their resources. Webster set out with photographer Jon Golden to examine the cod fishery in Iceland. Protected by an unmatched two-hundred-mile cordon against international fishing, Iceland has created one of the world’s few thriving fishing industries. Through careful management and painstaking-often painful-enforcement of catch limits, the tiny island-nation seems to have found a balance between economic development and long-term sustainability. They have shown, as Webster observes, that “with regard to fishing, the universe is both finite and possible to preserve.”

Jesse Dukes, with photographer Travis Dove, takes a similar look at the lobster industry in Maine. By way of an informal system of “lobster gangs,” the coastal waters there seem to have avoided the tragedy of the commons. By allowing old fishing families to self-manage the industry, Maine has ensured that its resources are protected by the fishermen themselves, who have the incentive to see that their businesses are passed down from one generation to the next. But some scientists worry that what best benefits a particular fishery may not necessarily be what is best for the entire ecosystem. This is especially apparent upon examining the bluefin tuna populations of the North Atlantic, as documented in this issue by Bart DiFiore and photographer Brian Skerry. DiFiore demonstrates that our knowledge of bluefin remains so incomplete that we cannot accurately judge the health of the population, much less presume to manage its harvest. Morever, every new piece of data is drawn into longstanding political arguments-often even before it can be more fully debated by the scientific community.

Similar questions about the future run through essays by Annie Murphy on salmon farms in the fjords of Patagonia, Lawrence Weschler on the crocheted coral reefs of Christine and Margaret Wertheim as they seek to sound the alarm about the effect of ocean acidification on the Great Barrier Reef, and Douglas Haynes as he examines Lake Xolotlán in Managua, one of the most polluted bodies of water in the world-the existence of which both creates the community there known as The Bottom and threatens the health of its residents.

Collectively, these stories allow a glimpse of a world that is both endlessly complex and imminently imperiled. More importantly, they demonstrate the degree to which our ability to save these precious resources-both for the healthy future of aquatic ecosystems and the healthy future of the human race-may rest on our willingness to share information without suspicion or fear. The cod fishermen of Iceland and lobstermen of Maine have a great deal to teach the scientific community, just as the scientists studying the Atlantic bluefin tuna populations and working to improve the water quality of Lake Xolotlán have a great deal to teach the fishermen who venture into those waters.