- Tamara, a descendent of the Ormeño family, lives in Pagancillo, a tiny village just a few miles from Aicuña. At nine years of age, she already has undergone two eye operations. Doctors advised her parents to paint her school desk black to protect her eyes from the glare of the sun.

Every so often someone shows up in Aicuña asking about “the mysterious albino town.” The curious or nosy make a twenty-hour bus ride from Buenos Aires to the almost secret hamlet in La Rioja Province of Argentina.

It’s Monday morning, and someone has just arrived.

The photographer Paola de Grenet and I are having breakfast at La Casa guesthouse—the only accommodation that exists in Aicuña—when a taxi parks in front of the yard. A man in his thirties emerges, with neatly parted hair, designer eyeglasses, and a leather briefcase.

Up until October of 2005—barely more than a year ago—La Casa was just a family ranch owned by the Ormeños, so the entrance doesn’t lead to a lobby but directly into the dining room. There, besides the photographer and me, sits Doña Josefa, the Ormeño widow and an owner of the guesthouse.

“Good morning,” says the man in Spanish as he comes through the door, with an obvious foreign accent. “Do you serve breakfast here?”

“Yes,” replies Doña Josefa. “Come in, have a seat.”

Doña Josefa’s invitation comes off as laconic. If Paola and I didn’t already know her a bit, we would have said that this grandmother was distrustful of strangers. The first impression she gives is that something—a memory, a loss, a trial—has hardened her countenance. Or that she’s in a bad mood. Or both at the same time.

“What is there for breakfast?” asks the foreigner, smiling, trying to make friends.

“The regular,” says the woman, “coffee, milk, bread, butter, cheese.”

“Anything else?”

“Why don’t you tell me what you want and I’ll let you know if I can make it for you.”

Paola and I keep quiet. She busies herself by flipping through a book on the table. I busy myself by watching her.

“Bacon and eggs, maybe?”

“Okay, bacon and eggs,” repeats Doña Josefa, disappearing into the kitchen.

The young man sits down with us. His name is Benedict Mander. He’s British, a journalist for the Financial Times of London. We ask him what brings him to Aicuña. This is a place, we remind him, that’s not on the way to anything and where no one just ends up.

Benedict Mander smiles at our question.

The truth is, to get to Aicuña you have to want to get there, fervently and with great effort. It’s a hundred and fifty-five miles from the capital of La Rioja, and six miles from the closest road—which is more of a pebble-strewn path than an actual road. Aicuña doesn’t appear on most maps. Some of Aicuña’s inhabitants say it’s an almost forgotten town at the end of the world, farther from Buenos Aires, geographically and culturally, than the Andean hamlets in Bolivia and Chile.

“I guess I’m here for the same reason you are,” he says in English, nodding his head toward Paola’s book, Anthropologies of Art.

Mander is about to start laughing. It’s obvious that all three of us have come for the same reason, drawn by the story of “Aicuña, the mysterious albino town.”

But Paola does not seem interested in making alliances. Her face grows serious, her eyebrows drawn together.

“How long are you planning on staying?” she cross-examines suddenly, also in English.

“Just today,” he says. “I asked the taxi driver to come pick me up this afternoon.”

“Then you won’t be able to get anything,” she says. “I mean, it would be best, for all of us, if you don’t even try.”

The Financial Times correspondent is shocked, agog.

“The people in this town don’t like to talk about that subject,” she explains. “We’ve been here for two days and we still don’t know if we’ll be able to speak openly with anyone.”

A few minutes later, Doña Josefa comes back carrying a tray with milk, coffee, bread, butter, and two fried eggs with bacon. Mander thanks her, dips a piece of bread into the egg yolk and takes his first bite.

For a little while, Mander, Paola, and I continue chatting in English, on all sorts of topics: how long we’ve been in Argentina, how old we are, whether we have kids. When Doña Josefa returns to the table, we switch to Spanish.

It is she who asks Mander directly: “What is it that brings you here?”

* * * *

A study by John Hopkins University estimates that there is one albino for every seventeen thousand people in the world. In Aicuña, according to Julio César Ormeño, the head of the Vital Records Office, there live about three hundred people. At its most populous, he says, there have been three hundred and fifty. The town is so small that every inhabitant—including the newborns, the elderly, and the church minister—could fit into a movie theater.

Of that total, the head of the Vital Records Office has taken census of four albinos, all men—three that currently live in Aicuña and one who moved to another town two hours away. But his archives also say something more: since the end of the nineteenth century, forty-six albino births have been registered in Aicuña alone.

According to the math, the rate of albinism in Aicuña isn’t one in every seventeen thousand people but rather one in every ninety. Or as Dr. Eduardo Castilla, the author of “Aicuña: A Study of the Population’s Genetic Structure,” maintains: albinism is almost two hundred times more likely to occur in Aicuña than anywhere else on the planet.

Despite the proof if its prevalence, there is some kind of unanimous censorship exerted over the discussion of albinism in Aicuña. The world albino is rarely spoken aloud—as if it were a taboo, one of those dark family secrets that can be ignored if no one speaks of it.

But Benedict Mander doesn’t share that code of silence. So he ends up confessing, not without a certain cautiousness, what has brought him here.

“I came,” he says quietly, “to meet the albinos of Aicuña.”

As if she has been waiting for this moment, Doña Josefa gets up from her chair and goes to look for the guestbook.

“Here, read,” she says to Mander, handing him the book, which is open to the middle.

It is the same message that she had made us read—the one by Carlo Brero, a nearly eighty-year-old Italian who, on September 28, 2006, bade his farewell to La Casa with these words, in Spanish: “I came to this town to find albino genes and I found the happiness of my youth.” Mr. Brero’s farewell letter, written in a trembling hand but with unwavering care, takes up the entire page. Before signing it, he added: “I feel personally content and I think that it’s because of the way of life here: happy children, simple, tranquil, and affable people. Love is found here amid an everyday landscape.”

When Mander finishes reading, Doña Josefa stares into his eyes, as if questioning him while at the same time trying to get her point across. Her gaze says, “You see, Aicuña is much more than an albino town.”

Paola and I watch the scene with interest and repeat the bad news: that we haven’t even seen a single albino since we arrived. What’s more, we have no guarantee that we’d be able to see one in the next few days.

We had already been warned along the way—the people in this town tend to be unsociable by nature, though if they feel comfortable with visitors they can also be very friendly, welcoming, and generous. But it makes them extremely uncomfortable when someone comes looking for albinos as if they were going to a freak show. Some of them openly admit that the presence of journalists bothers them.

Ever since a Buenos Aires magazine called 7 Días published a feature story on Aicuña’s albinos in the early eighties, the town’s inhabitants have been wary of the press. The story’s effect was immediate and, for them, unwelcome. People began to arrive hoping to meet albinos. They wanted to see them, photograph them, find out what they were like and how they looked, to discover what daily life was like in the town they imagined—one filled almost entirely by people with white hair and translucent skin.

Aicuña was unaware of its peculiarity until the gaze of the outside world revealed it. As in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, the world pointed its finger, and suddenly it was as if the whole town were monstrous and all its inhabitants both grotesque and yet somehow beguiling at the same time. Ever since then the town has been protective of the albinos who live there and evasive, even surly, toward outsiders

“One day a photographer came who wanted to take our picture,” Lucio Ormeño, one of the three albinos living in Aicuña, will tell me a few days from now.

When he speaks, Lucio Ormeño never refers to himself in the first-person singular. Instead he prefers to use we to talk about himself, even for such simple matters as we woke up or we had a business or we bought a motorcycle. It is a strange way of speaking, which is in no way a shared trait among the residents of Aicuña. It is he, and only he. It’s as if excessive modesty—or excessive something—has hindered him from expressing his individuality, even as the world regards him as so singular.

“We paid him no mind,” Lucio Ormeño will continue, in his lonely plural. “He asked us questions, he pleaded, he begged. He was desperate, but he went back to where he had come from without a single photo. We wouldn’t even pose for his camera when he offered us money.”

Lucio Ormeño will be the first person with that rare genetic condition called hypomelanism with whom I speak in Aicuña. But it will be a few more days before we do. Now, Benedict Mander, Paola, and I ask ourselves if we had done the right thing in coming here. To the so-called town of the albinos.

After her first encounter with Mander, Doña Josefa has gone back to being the sweet, charming hostess that we have been enjoying—and will continue to enjoy—during our stay in Aicuña. She offers us more coffee, asks if we need anything, and announces what she is making for lunch that afternoon: breaded steak filets. She also says that when her son Dante comes back, he will surely find some way to help us. And he should be on his way now, she adds, since he only went to check on the watering of his orchard of walnut trees.

Dante Ormeño runs La Casa with his mother. He is a robust man in his forties, no taller than five foot six but with a woodcutter’s back and arms that make him seem larger. His face is red from summer sun and covered by a thick beard and unruly bangs, which he tries to comb to one side but which keep falling over his forehead. One of Dante Ormeño’s characteristic gestures is this attempt to keep his hair in place. He does it often, and without the least bit of vanity, but it is hopeless.

He is also a quiet man. Argentineans are renowned as consummate conversationalists, or less generously as know-it-all chatterboxes, but Dante Ormeño is quite the opposite. It is highly unlikely, unless you are a close friend, that he will be the one to start a conversation. With someone like Dante Ormeño you have to make the first move. But, contrary to appearances, he will always comply.

Benedict Mander sums up his story for Dante Ormeño, saying that this afternoon a taxi is coming to pick him up, so he has little time, and will Dante show him around the town.

And against expectations, Dante Ormeño complies.

They agree that Mander will see Aicuña from the passenger seat of a pickup. After midday, we will meet back up here for lunch. Then, Benedict Mander will leave Aicuña; as Lucio Ormeño would say, he’ll “go back where he came from.”

* * * *

In Aicuña it seems as if everyone’s last name is Ormeño.

The head of the Vital Records Office, in charge of keeping track of the births, marriages, divorces, and deaths in the town, who gave us statistics on Aicuña’s population is named Julio César Ormeño. The president of the Neighborhood Center, responsible for, among other things, distributing the scarce water for the crops, is Marino Ormeño. The secular minister who also acts as priest—because Aicuña’s only church doesn’t have one—who celebrates the Sunday masses, gives Communion, baptizes, and hears confession for the devout is Don Alberto Ormeño. The nurse who serves as a doctor and runs the Primary Care Center—a spotless first-aid post that transforms into a hospital when need be—is Mrs. Irma Oliva de Ormeño. The owners of La Casa guesthouse are Doña Josefa, the widow of an Ormeño, and her four children, including the manager, Dante Ormeño. The best student in the only school is Julián Ormeño. The only taxi driver, Juan Edgar Ormeño. And the four living albinos born in Aicuña are also Ormeños: brothers Lucio and Elio Ormeño, and another pair of brothers—not directly related to the first—Toto and Lucas Emilio Ormeño.

Lucio Ormeño is the manager of Aicuña’s telephone booth. People in Aicuña don’t have personal phones, so they give and receive calls in Lucio Ormeño’s booth.

Every time the telephone/fax machine in his small office rings, he picks up the receiver, waits a few seconds for the call to go through, and, sitting with his back very straight and his eyes fixed on some vague point beyond his dark glasses, calls out, with the booming voice of a radio announcer: “Bo-ooth!”

It’s almost always someone he knows. In a town of three hundred souls that’s not much to brag about, but Lucio Ormeño can also claim to have memorized a few dozen phone numbers. Sometimes, since his phone has a little screen for caller ID, he even pleasantly surprises the callers by addressing them directly by their last names.

“Hello, Carrizo,” he now greets someone calling from a nearby town.

It’s almost seven in the evening, but the streets are still lit by the summer sun.

Lucio Ormeño’s telephone booth, which is to say his entire office, must be about sixty-five square feet. There, apart from a cubicle where customers can have private conversations, is a wooden desk and a bookshelf that holds telephone books and notebooks in which he has written down certain numbers and emergency addresses. The only decorations on the walls are an enormous golden clock and a string of small lights that he arranged in the shape of a Christmas tree.

Lucio Ormeño works from eight thirty to noon, and from six thirty to nine in the evening. That is, of course, when there is no interference on the line, because in that case, he says, his office remains closed until the problem has been resolved. He only takes care of the simpler breakdowns, such as replacing worn-out wires and connections. He doesn’t receive a salary for this full-time job, just 20 percent of the price of each call made from Aicuña. The calls he answers for his neighbors are free.

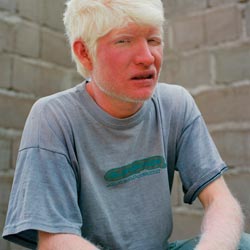

Just like his brother, Elio, Lucio Ormeño is albino, but this is one thing he is unwilling to discuss. He tells me that he studied until seventh grade, when the town’s school went only that far. Now he is thirty-nine and he feels a bit too old to sit at a desk next to young boys.

In spite of his age, Lucio Ormeño has a boyish look and smile. His face is very round and red, with the tiny eruptions of a rash caused by the desert mountain sun. And that’s just in the summer; in this harsh region, winter burns the skin as well with its fierce mix of dry air, relentless winds, and subfreezing temperatures.

In order to protect himself from this aggressive climate, Lucio Ormeño always wears a long-sleeve shirt, preferably plaid, its straining buttons offering a glimpse of the cotton T-shirt underneath. It is rare that he’ll be seen without sunglasses and a baseball cap. His white hair, which has been dyed blond, peeks out from underneath.

When he has finished talking with Señor Carrizo, he takes a piece of paper and jots down a message the caller has left for one of the townspeople of Aicuña.

That’s how he always does it, with all the calls he receives. If the message is urgent, Lucio Ormeño will go out to the street and find some kid playing nearby who can deliver it immediately. Otherwise, he holds on to messages until closing time and, on his way home, delivers them himself.

The kids love him. Almost every one that passes by the booth comes in to say hi or to tell him something.

“Before the booth we had another business,” he says, always using that we, “a food shop. The kids would come there and we’d give them candies, chocolates, little stuff like that.”

He smiles as if he were a child himself.

“Then, when we opened the booth, we kept bringing sweets. Now we don’t do it as often. We had to shut down the food shop because Mama got sick.”

I ask him if he had to study something in order to work in the phone booth.

“They gave us some training,” he says, no longer smiling.

Then he thinks for a bit, as if remembering something, and adds, “They organized a contest for the booth. We won it.”

Lucio Ormeño is also interested in photography. It used to be his hobby. In the early eighties he had taken a correspondence course that he was unable to finish, because at that time Aicuña’s postal service was—his smile returns—worse than it is now. He still has his camera, just in case, though he’s been told that the type of film it uses is no longer made.

He draws in the air with his finger something that looks like a pair of binoculars.

“Yeah, they were those 110-millimeter rolls, with those photos that came out very small, remember? Beautiful!”

I’ve never met someone who uses the word beautiful more than Lucio Ormeño.

He tells me about his childhood, when he and Elio would accompany their father to the highest hills to fix the antenna of the only television channel in Aicuña. He calls these “beautiful times.” The vegetation in the areas basically consists of desert carob, walnut trees, poplars, and cacti, all of which he describes as “beautiful landscape.” On a predawn excursion with Dante Ormeño and Paola, to take night photos in the area around town, Lucio Ormeño would manage to also call “beautiful” the night, the moon, the road, and the mountains.

After a few days of talking to Lucio Ormeño, one realizes he feels that anything undeserving of the adjective—beautiful—doesn’t deserve his consideration. What isn’t beautiful is simply ignored, or evaded, or left in silence.

“We don’t have to take care of ourselves,” he answered, for example, very curtly, when I asked him if he had to have some type of special medical treatment as an albino.

Then right away, as if gauging his words better, he admitted, “We only have to see an ophthalmologist once in a while. For the eyes, you know?”

For a few seconds he shifted his dark glasses. He didn’t remove them. He just lowered them to the tip of his nose. His pupils were pink, proof of a type of albinism, called oculocutaneous, that affects the entire body: the eyes, the skin, the hair. His pupils also vibrated, from one side to the other, with that involuntary movement known as nystagmus.

It was impossible to broach that subject again with Lucio Ormeño.

* * * *

The nurse that runs the Primary Health Care Center, Mrs. Irma Oliva de Ormeño, is the mother of the other pair of albino brothers, Toto and Lucas Emilio Ormeño. The first time Paola and I saw her, Mrs. Irma was leading a procession in honor of the Virgin of the Rosary, the town’s patron saint.

It was Sunday and the church bells were ringing to gather the devout. At eleven in the morning, the prayer hour, there were around twenty people in church, mostly women and children. By two in the afternoon, when the procession had already marched along the entire stretch of the only road in Aicuña, maybe forty more had joined, including some men that followed the rite from the doorways of their homes. Inside, on the television screens, an important soccer game of the Argentinean league was about to start.

Mrs. Irma also led the prayers. “I put my hope in you, Lord,” she recited, “and I trust in your Word.”

Almost everyone knew the litanies by heart.

Besides working as a nurse, Mrs. Irma serves as the caretaker of the church. She is in charge of making sure that the chapel is decorated with fresh flowers, that its altars and saints are always clean, and that the enthusiastic religious fervor that has characterized Aicuña throughout its almost three hundred and fifty years of existence doesn’t wane. In order to fulfill this task, she organizes prayer sessions to teach the children the mysteries of the rosary and tries to ensure that the parish priest assigned to the town, Father Enrique Martínez, comes to celebrate Holy Communion at least twice a year in addition to weddings and funerals.

As a result, Mrs. Irma’s daily routine is divided between the ten hours she spends working at the Primary Health Care Center and the significant time she devotes to the church.

“Sometimes I also have to act as psychologist and spiritual adviser,” she says one morning when we come to find her at the infirmary.

She has worked here for the last eighteen years, and it is clear that a large part of her personality has rubbed off on the Primary Health Care Center. The place shines so impeccably, is so ordered and immaculate, and smells so scrupulously disinfected. One can see that the red cement floor is waxed and polished every day. The white walls don’t have a single stain or crack. The chairs in the waiting room, also white, are all identical. In every room there are signs that reiterate her goals over the years: promoting breastfeeding, preventing uterine cancer, emphasizing the duties of fatherhood. Beside each announcement there is a religious image. A cross, Christ, the Virgin of the Rosary.

It is obvious that Mrs. Irma, thin and short, always dressed in a suit, is attentive to every last detail, even when she speaks of her most intense emotions.

For example, when talking about her children.

She has seven. The married ones have moved to nearby cities: larger, more modern places than Aicuña. With her and her husband remain the two albinos—Toto, the eldest of the seven, and Lucas Emilio, who has just finished high school—and an eight-year-old daughter.

“Toto,” she says, “is the more introverted, although maybe the proudest as well. His brother dyes his hair blond. He takes better care of himself. He would take off right now to travel the world. Not Toto. He tells me: Let me be, Mama. This is how I was born, this is how I am. One has to thank God for what one is given.”

Suddenly, without losing her serenity, her expression clouds over. Mrs. Irma also remembers that feature story in the magazine 7 Días, which seems to have created a dividing line in Aicuña’s history. She feels the gaze—perplexed, fascinated, perhaps clumsy—of outsiders insisting that Aicuña is not just an ordinary town.

“They caused us a lot of pain,” she says with the remote resentment of those who have been brought up to forgive affronts. “They said many lies: that albinos don’t see well and that they can’t work because of that. That boys like my sons were a burden on their parents. That Aicuña was a weird town where we were all albinos. People began to feel ashamed, as if there were no other albinos in the world!”

She stops suddenly and sighs, as if attempting to regain control of her emotions.

“That’s God’s will,” she says, and to a certain extent she seems to consider our conversation finished. “There’s nothing weird here. Nothing that doesn’t happen in other places.”

Implicitly, Mrs. Irma confirms what one senses about the conception of albinism in Aicuña. People seem to view it as more than a genetic condition, as though it’s a quirk of fate, like being born left-handed, shortsighted, or flat-footed. Although one can trace a predisposition for those characteristics in the family tree, in the end it is destiny, luck, or God that has made the final decision.

In the end, some people have it, and some people don’t.

Not even Mrs. Irma, an objective and scientific medical professional, is willing to discuss the possibility that the high rate of albinism has something to do with that one thing in Aicuña that is impossible to ignore—that nearly everyone shares the last name Ormeño.

A few weeks later, Father Enrique Martínez explain, “It is very likely precisely because of that, because almost everyone’s last name is Ormeño, that no one wants to talk about that subject in Aicuña.” Seated in his office in the church at Villa Unión—the closest thing to a city near Aicuña—Father Martínez tells me that he has known the small town for twenty-five years and has been the priest assigned there for a decade. He also says that he has heard a terrible rumor, which seems to have started circulating around the region after the 7 Días article. Some people say that the large number of albinos born in Aicuña is a kind of divine punishment for the incest that its inhabitants practiced for centuries.

Within Aicuña, there is never a single mention of incest.

For those unfamiliar with the town’s history, it makes sense to be suspicious. After all, eight out of every ten residents of the town bear the last name Ormeño. One would assume that at some point there must have been children born of direct relatives. What’s more, in Argentina only the father’s last name is passed on, leaving open the possibility that many more Ormeños are Ormeños on their mother’s side as well. Malicious speculation combined with notions of divine punishment lead easily to uninformed accusations of sexual misconduct.

“It isn’t true,” says Father Martínez. “But it is very difficult to explain to people the difference between an inbred, closed-off, isolated community that is interrelated for numerous historical reasons, and an incestuous community.”

Inbreeding is not the same thing as incest, as any pocket dictionary will tell you.

Inbreeding is the marriage—or biological crossing—between people with common ancestry or who were born within a small village or genetically isolated community. Incest, on the other hand, implies a direct degree of kinship: which is to say, when there are sexual relations between siblings or between parents and children.

Nonetheless, the popular imagination can be very powerful, and very cruel.

It’s like something out of García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude. Once upon a time in northeastern Argentina there was a village of grape and almond farmers and goat breeders. This place, called Aicuña, also known as “the town of the Ormeños,” or later “the mysterious albino town,” remained isolated for more than three centuries, two hundred and fifty years longer than García Márquez’s Macondo. Inbreeding was punished in Macondo by the birth of a boy with a pig’s tail. In Aicuña, say some vicious people in neighboring villages, the punishment is colorless children. Forty-six of them, to be precise, in little more than a century.

However, it seems that Aicuña’s isolation has something to do with those same villages that now spread rumors about its strangeness. Some say that the animosity and subsequent estrangement all began with a disagreement over property. Who owned what land. Or who wanted to take over what land. But that is another story—another taboo—which almost no one here wants to talk about.

* * * *

Aicuña has no main square and just one road.

It is a long road, curved and steep, bordered by small hills, that begins at almost five thousand feet above sea level and ends closer to six thousand feet up. It is a dirt road that most people cover on foot, although the young men prefer to do it on horseback and the kids by donkey, with groups of up to five on one animal’s back.

The houses rarely face one another, but instead alternate in a zigzag pattern: one house on the left side, with a garden beside it, and opposite that garden a house on the right side, with its own garden, and so on. Some of the older houses don’t even have doors that open onto the road. You have to enter them by going around through wood or wire fences in the side garden. The real front door—what one would simply call the entrance—is on the other side, facing the hills.

It is as if, when you arrive in Aicuña, half the town has already turned its back on you.

It is hard to forget how it feels the first time you walk down that only road. During siesta, between two and five in the afternoon, it looks as if no one lives there. But as you walk uphill, there are moments where you have the distinct impression that someone is watching you from behind.

It is a strange feeling. You turn around suddenly, trying to catch the sneak that’s surely hiding in a doorway or lurking behind a curtain, but you don’t see anyone.

One afternoon, after lunch, we are relaxing on the splendid terrace of Doña Josefa and Dante Ormeño’s guesthouse. It rises about three feet above the dirt road. From that height, on armchairs fashioned from iron poles whose seats are lined with calfskin, the town looks like the setting for an old Western.

Since it’s siesta time, the setting is deserted.

“Listen,” Dante Ormeño says to Paola and me, “you don’t hear a thing. That’s why people here are able to make out the slightest noise and can tell, by the way the motor sounds, whether the car that’s coming belongs to someone they know.”

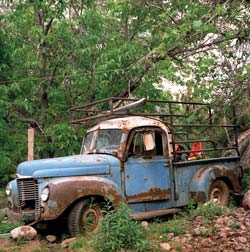

Dante Ormeño says he isn’t exaggerating. When he was a boy, his father taught him to recognize the light truck of a vendor that came once a week bringing food that wasn’t readily available in Aicuña. He remembers that he learned to identify the motor from several miles away. “Here comes Don Lulo,” he would say to himself, and he was right. And just like him, many others could do it, too.

“Except for one period when a bunch of buses came here, Aicuña has always lived in a state of almost total isolation,” Dante Ormeño continues. “Now things have changed a bit. There are some who want more people to come, who want the town to open up, who want the young people to know there’s another world out there, but it’s not easy.”

He doesn’t say it, but he’s surely one of these people determined to see things change in Aicuña. Not only has he, along with his brothers and mother, opened up La Casa guesthouse, but he has also convinced the walnut farmers to improve their crops so they can access new markets. Every Saturday, he is one of the most enthusiastic participants in a soccer tournament that about fifty townspeople take part in (the women just watch, for now). For the guesthouse he bought a Ping-Pong table, a volleyball net, a computer connected to a sound system, and an enormous television that gets satellite channels, all of which everyone in town can use for free.

Since La Casa opened in Aicuña, it’s obvious that Saturday afternoons are more dynamic.

On most Saturday nights some of the town’s young men get together to make music or play cards while drinking beer. The beer is almost always the dark kind with that sickly sweet flavor. They drink it here in liter bottles and share it around.

Julián Ormeño, a seventeen-year-old boy whom his teachers consider their most diligent student, thinks that things really started changing a few years ago when Dante Ormeño came back to the town to live. He was the one, says Julián, who, among other things, taught him to play the guitar.

Dante Ormeño is perhaps one of the few in his generation that left Aicuña in search of opportunities, held several jobs (including managing a winery), and then came back. As we relax on the terrace, I ask him why.

“My father died before he could build this guesthouse. It was his dream.”

Many people remember his father, Don Ambrosio Ormeño, as the last patriarch of the town. He was the school principal; he organized the walnut growers’ cooperative; he got loans to build houses with good quality materials; and he always believed that if he opened up a guesthouse it would attract the type of tourist that looks for peaceful spots to spend the weekends. He believed that contact with outsiders would be good for everyone in Aicuña, and not just economically.

“Here,” continues Dante Ormeño, who has now lit a cigarette and smokes leisurely, “we are like one giant family. Anything that hurts a few of us hurts us all. And you can’t just look away when something is hurting your family.”

Dante Ormeño must feel deep down that he has inherited his father’s convictions and his goals. Through his work, La Casa is now recognized as a tranquil place to spend a few days. He is determined to help his neighbors appreciate the connections the guesthouse builds, even though that means changing the unfriendly attitude some of them have toward strangers. Like his father, he must believe that one thing leads to another.

The people’s introversion, and the resulting isolation, may be blamed on the albinos of Aicuña. One may think that the villagers, feeling like the objects of outsiders’ freak curiosity, learned to become unsociable, surly, and evasive as, over the years, they closed themselves off from the world.

But that’s not the case.

In fact, it’s the reverse; the high rate of albinism is actually due to Aicuña’s long history of segregation. The isolation gave rise to the albinism, not the other way around.

If Aicuña hadn’t spent three hundred and fifty years in near isolation, without mixing with people from other places, it would have been statistically impossible for forty-six albinos to have been born there in little over a century. For someone to be born albino, both their mother and their father have to be carriers of that gene—a coincidental union that only occurs one out of every seventeen thousand births. However, in a town where eight out of every ten people are Ormeños, it’s more likely that both parents carry similar genes. They don’t have to be direct family members: it’s enough that—even if distantly—they both descend from the same branch. And it seems clear that the widespread Ormeño family is the source of this particular gene.

The people of Aicuña have kept a painstaking record of their town’s genealogical history, but it is not stored only in the archives of Julio César Ormeño’s Vital Records Office. The history is alive in the memories of the villagers. Many of them—and not only the old people—can recite a succession of marriages and births spanning at least fifteen generations from 1663, when Aicuña was founded, up to the present day.

This genealogical history is also an economic one, a history of struggles over land ownership.

The land that makes up Aicuña was originally purchased by the Spanish general Pedro Nicolás de Brizuela to pass along to one of his illegitimate sons. During the Spanish colonial period in the Americas, only so-called legitimate sons could legally inherit land, so in his will General de Brizuela wrote that he wanted his illegitimate son, “this poor man, to have the benefit of a piece of land with which he can support himself, and if any son of mine tries to take it from him, he will incur my curse as someone who goes against the wills of both God and his father.” Nonetheless, the legitimate sons, of which there were eight, tried several times to appropriate the property from their brother.

Two of these sons were albinos.

According to Dr. Castilla’s study of Aicuña, the two albino sons prove almost definitively that the general was the region’s original genetic carrier of hypomelanism. But General de Brizuela bequeathed the townspeople more than his recessive gene; he left the future inhabitants of Aicuña a legal battle over its ownership that has created a legacy of suspicion and distrust of the outside world.

While the legitimate descendants of the general could marry people from other villages without fear of rightful claim to their property—and dilute the presence of the albino gene in their line—the descendants of the general’s illegitimate child, the first settlers of Aicuña, paired off and had children with their neighbors.

Thus, the explanation of how the Ormeños came to dominate the population is simple: the first Ormeño was a Peruvian immigrant who had eight children with a woman whose only sister had just one. Out of nine children, then, eight were Ormeños, but while they are “one giant family,” as Dante Ormeño says, where every neighbor is also a relative, the bloodline is not necessarily a direct one.

In fact, each new generation memorized their family tree, in part, to avoid marrying too closely. But they also learned their familial inheritance by heart, in order to collectively defend themselves in land ownership trials. Of course, this family tree got more complex and tangled with Ormeños over time, but this too was a defense. If every villager could prove a direct line from de Brizuela, no one could dispute their rights. They refused to intermarry even with his legitimate descendants for fear these distant relatives might exploit the bonds of marriage to try to appropriate their lands. Better to remain within the small circle of closer family. Better to hide away.

For more than three centuries Aicuñans protected their lands by closing the village off from the outside world and shunning all visitors from there. Those who could not stand the claustrophobic grip fled, never to return. Those who stayed, inevitably, continued the inbreeding. This significantly raised the probability that both parents could be carriers of the gene, and that an albino child would be born. Thus, the illegitimate son inadvertently safeguarded his inheritance far better than his legal siblings.

But Aicuña is not an albino town. There is nothing deviant here to satisfy our more prurient desires. The whispers of divine punishment for incest are mere myth. And yet there is something archetypal, even tragic, about Aicuña—an entire lineage imprisoned by their own distrust, preferring estrangement from the world to the prospect of being judged illegitimate and having to surrender their inheritance.

In the meantime, three centuries have passed Aicuña by. Isolated geographically and culturally, the inhabitants are little prepared to cope with the twenty-first century. In the face of outside curiosity, rumor, and intrusion, most have retreated further into reactionary seclusion, turning decisively, and distrustfully, inward. This response to the hurtful whispers of its neighbors about Aicuña’s alleged sin and strangeness and to nosy journalists and vacationers looking for a thrill, can no longer protect Aicuña’s way of life. Trade, communication, globalization, and other facets of the modern world pose frightening hazards to a village that wants only to be left alone. Aicuña, as I have found it, with boys riding donkeys through the dust, with its lone taxi and its communal telephone, will not survive this century unscathed. Whether it grows or dies, it will not pass another hundred years in isolation.

Dante Ormeño, welcoming villagers and tourists alike to sit in front of that one big screen TV, is hoping Aicuña will break out of its self-imposed isolation. Eventually, he hopes, the village will become integrated with the outside world. Once it embraces this idea and allows the world in, the village may lose some of its mystique, some of its precious identity, but with these, certainly will go its predisposition for albinism—and the prying curiosity of outsiders.