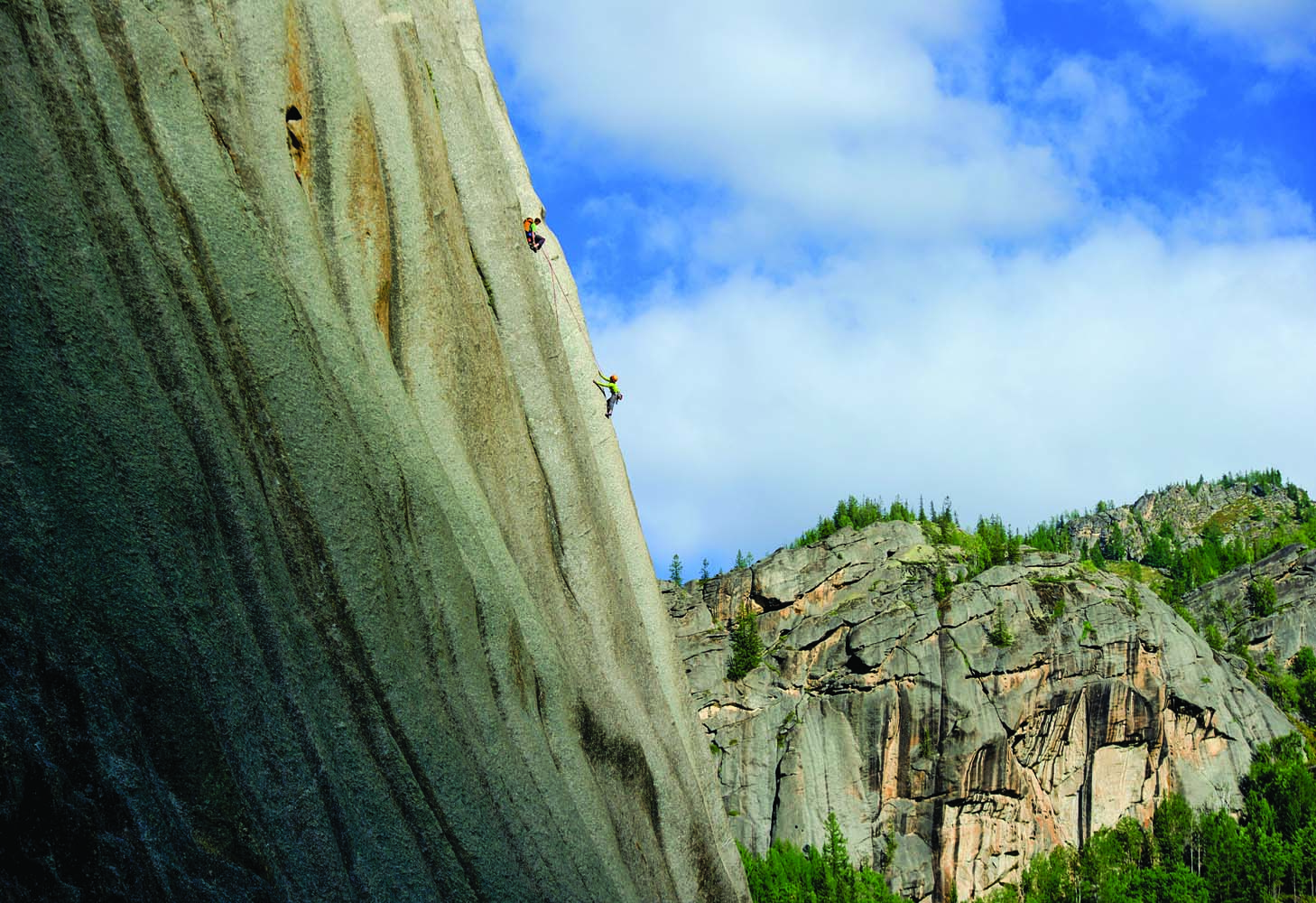

Foreigners are not allowed in newly opened Keketuohai National Geological Park. But, drawn by a hundred 1000-foot granite domes that rise above the coniferous forests and the gushing, emerald-green Irytish River, how could we stay away?

Daryha, forearms hefty from almost a half-century of milking mares, wipes the splatter of yogurt off her cheekbones, adjusts the scarlet scarf on her head, and proudly says: Azer men mal kasebi men chuhel danbayten boldem—“I am a nomad no more.”

For centuries, here in the northern tip of Xinjiang province in western China, a stone’s throw from Mongolia, Daryha’s family moved their herds of sheep, goats, and cattle up into the Altai Mountains in spring. It was a fifteen-day journey, all the family possessions, including the felt-wool walls, eighty-four ribs and the circular wooden ring of the family home, the yurt, strapped onto the double hairy humps of four camels.

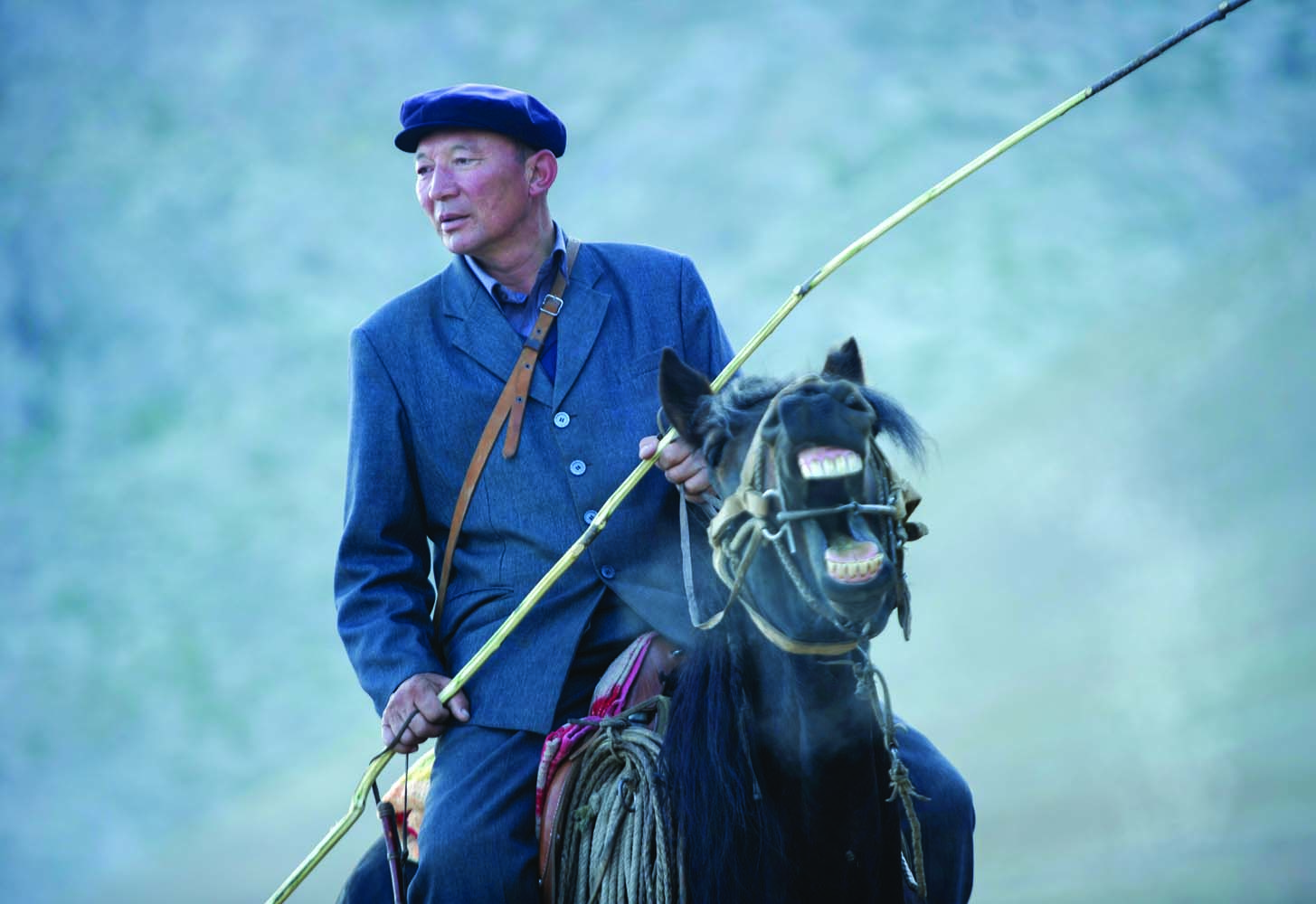

They were cowboys. Everyone, even the toddlers, rode horses. They followed the melting snow up into the alpine pastures, erected their yurt in a field of wildflowers, and lived on mare’s milk and mutton for three months. The sheep grew fat, the goats fit, the horses and humans lean. This seasonal migration was repeated in reverse in autumn, the nomads retreating out of the mountains down into smoky, mud-walled homes on the wind-scoured steppe.

It was a good life, admits Daryha, who is forty-eight years old, but a very hard life. Her solid bulk illuminated by a shaft of light pouring down through the circular hole in the ceiling of her yurt, she refills my bowl with fresh, lumpy yogurt and pushes a cup of sugar toward me. Daryha sewed the embroidered, brilliant-red walls enclosing the yurt’s wooden lattice, by hand, over the course of many years.

Disobeying explicit permits from the Chinese border police, we—seven American climbers—have spent the night in Daryha’s yurt, deep inside Keketuohai National Geological Park (pronounced koi-koi-toe-high). Daryha has transformed her hand-woven home into a guest house for park visitors. Keketuohai, a small park of 238 square miles, opened in July of 2008. Advertised as China’s Little Yosemite, it contains some one hundred gorgeous 1,000-foot granite domes that rise above the gushing, emerald-green Irytish River.

Daryha’s yurt, with its exquisite rug floor and the promise of beef boiled to perfection, is only a short walk from Keketuohai’s two predominant features, the Divine Bell and the Small Bell, massive, imposing granite walls that resemble Half Dome in Yosemite, although considerably smaller.

Our team has just made the first ascent of these two magnificent walls: climbing lightning-shaped fissures, getting burned back to the ground from scorching heat one day, washed off the face by freezing rain on another, finally reaching their summits, naming one line “For Whom The Bells Toll,” the other “Something Divine.” All of which means absolutely nothing to Daryha, whose pastoral ancestors pushed packed camels beneath these monuments of stone for generations without ever climbing them.

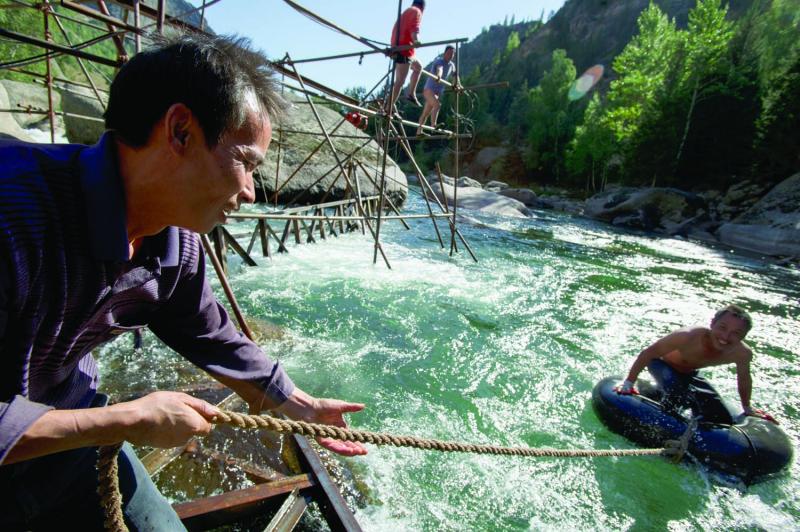

And yet this juxtaposition—the pastimes of modernity crashing into the path of ancient traditions—is at the very core of Keketuohai, one of China’s newest national parks. Daryha herself is a paradigm for this cross-cultural collision. Only five years ago there was nothing but a horse trail along the icy, snow-fed Irytish. Today the park has built a curling, one-lane, ten-and-a-half-mile concrete road up into the narrow valley. All visitors (99 percent of whom are rubbernecking Chinese with sun caps and cameras) are required to take a stretch golf-cart. In order to reduce pollution, congestion, and resource destruction, no private vehicles are allowed in the park.

Daryha admits that the new road has increased tourist traffic at her yurt. “Life is better now,” she says through Reza, my Kazakh interpreter, before handing me a business card with her cell phone number. “It is better to be a business woman than a nomad.”

The next day, still recovering from our climbs, we are seated cross-legged at low tables, having yogurt and meat inside another nomad’s yurt.

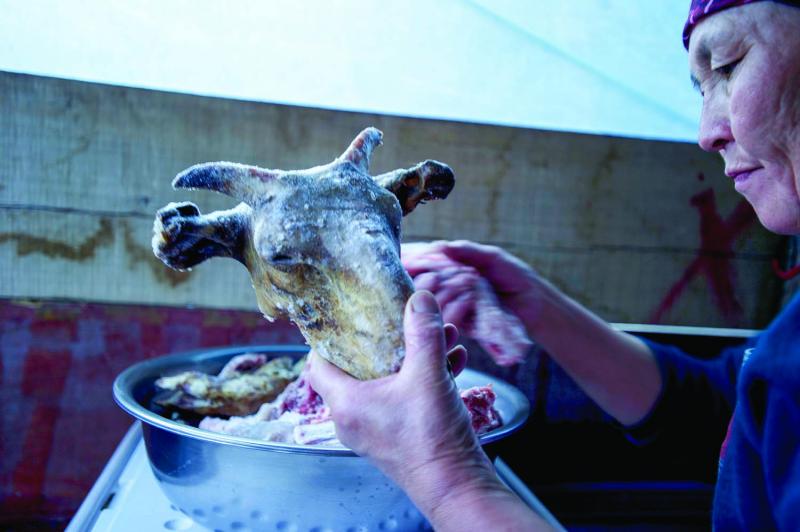

“I cook the meat, my daughter cooks the vegetables,” says diminutive Mapura. A river rock of a woman, she is wearing a vest, heavy skirt, and woolen socks.

Like Daryha, Mapura is a “nomad no more.” She also turned her family yurt into a guesthouse-cum-restaurant for tourists. Before Keketuohai officially opened, the park held a lottery, and some sixty lucky Kazakh families were awarded $90 permits to operate yurts inside the park. Mapura, age fifty-three, says that after her four daughters were grown, she didn’t have that much to do.

“But, being a nomad,” she says with a gold-toothed grin, “I knew how to cook Kazakh food—mutton, goat, horse.” There are approximately 14 million Kazakhs in the world, 10 million of whom live in Kazakhstan, 1.5 million in China’s Xinjiang Province, the rest spread throughout central Asia. Largely Islamic as a culture, and one that writes in Arabic script, Kazakhs are believed to be of Turkish and Mongol origin. They are traditionally pastoral nomads whose wealth was once measured in livestock. Because of communist policies in China and in the former Soviet Union, the majority of Kazakhs were forced to abandon the nomadic lifestyle two generations ago and now live in cities. The remote Altai Mountains are one of the last refuges of the nomadic Kazakhs.

Inside Keketuohai, which means “green forests” in Kazakh, there are several hundred nomadic families who use the Irytish River valley as a corridor to reach their high summer pastures.

Their herds constantly travel up and down the slim concrete road, splattering it with so much green manure that the park service, in hopes of not unduly tweaking tourists’ noses, employs a full-time shit-shoveling crew. Every two-hour golf-cart tour of the park is halted at least three times to allow the passage of herds of skittish sheep or stare-at-you-but-don’t-move cattle, or even the occasional nooses-through-nostrils camel train.

One cowboy named Hadek, in his mid-forties, in battered black leather boots and astride a giant brown bronco, stops to say that his herd consists of 106 cows, and that as long as he can keep running his cattle here, he has no problem with the valley being turned into a national park.

That seems to be the consensus of most of the nomads in the park.

Unlike what we Americans did in our national parks—forcibly removing all Native Americans, from Yosemite to Yellowstone to the Black Hills—the Keketuohai park management is allowing these seasonal nomads to remain. Less welcome are the three small, mud-hut villages inside park boundaries—Hayndbulak- tik, Tarate, and Baldbay—where sixty-one families live permanently year round.

“We want to remove these families from the park,” says Keketuohai director of tourism, Yan Li Hu, a woman in her mid-thirties, “but it is so hard to change their minds.” This resistance deeply disappoints the lean, stern Ms. Hu. As an incentive to leave, the park has built tenements for these families in the bleak, gemstone-mining town of Keketuohai, just outside the park.

I visit each of the idyllic, doomed villages. All three are surrounded by shimmering fields and lush pastures. “They want to build a tourist hotel right where my house is,” says Subethan, age fifty, a Kazakh with the deeply tanned, creased face of a life out-of-doors. “Hayndbulaktik, our village, is home to seventeen families and has been here for at least 250 years. We do not speak Chinese. We do not have job skills. How could we work in the city? Our life, our livelihood, is here with our livestock.”

Hayndbulaktik has no streets, just farmhouses and mud barns nestled side-by-side. Several women in scarves and skirts are out in the golden fields fiercely scything wheat. Three men wearing white, Muslim takiyahs and riding motorcycles are rounding up sheep.

Mapesh, a small woman in a neatly embroidered apron, whose cheeks are so high they are folding over, is sorting goats in her shed. Moving through the stampeding beasts, she grabs certain struggling animals by their horns and hauls them, easily, despite her size and fifty-seven hard years, into separate stalls. Some are for breeding, some are for eating, some are for sale, and some are for milking.

“Milk is necessary for every Kazakh,” exclaims Mapesh, “Kazakhs cannot live without milk!”

She invites me into a yurt-shaped building with whitewashed manure-and-mud walls, where I meet two of her five daughters, Wumethan and Berdan, milkmaids if I have ever seen any.

We share chunks from a loaf of tough, round bread—naan—bitter goat cheese, goat milk, cow milk, and sweet milk tea.

“Of course I don’t want to move,” Mapesh says staring at me with an expression of determination and sorrow. “This is my home. I won’t move.”

Before coming to Keketuohai, we naively imagined that we would be exploring a remote, unknown, wilderness-like park. But in Urumqi, the capital of China’s northwestern-most Xinjiang Province, a modern city of millions with a cityscape of construction cranes, we saw billboards advertising the park. A ten-hour drive north across the Dzungaria Basin, through the shifting sands of the Gurbantunggut Desert, brought us to Fuyin, the closest city to Keketuohai. There billboards of Keketuohai were on almost every street corner. At the park entrance we discovered a fleet of fifty new stretch golf-carts and the beginnings of a gigantic gateway museum. Designed by the same firm that built the Bird’s Nest for the Beijing Olympics, the behemothal structure has swooping waves of concrete meant to mimic the geology of the park.

But why should we have been surprised? This is twenty-first-century China. Highways and high-rises, pollution, people: just like every other First World nation. In the past two decades China has pulled a quarter of a billion people up into the middle-class. For the first time in their history, hundreds of millions of Chinese have spare time and spare cash—the first leisure class—and how do they want to spend their vacations? Just like Americans: visiting national parks.

In 2009, only six months after Keketuohai National Geological Park first opened, it had 140,000 visitors. Tourism director Hu said they plan to soon have more than a million visitors a year.

“We hope Keketuohai will make money,” Hu told me brightly. “We want this park to be a very successful business.” Excuse me?

Hu nodded with enthusiasm and explained that the Shandong Zibo Shang Sha Group, a developer that also owns hotels, shopping malls, car retailers, a company with more than 10,000 employees, has so far invested one-fifth of a billion Yuan ($25 million) into Keketuohai and plans to eventually spend three-quarters of a billion Yuan ($100 million), which includes the construction of a 1,000-bed, four-star hotel.

In other words, Keketuohai is a private national park. The Shandong group purchased a fifty-year lease on the valley and is doing all the development. They own the whole shooting match—the concrete road, the golf-carts, the typically inscrutable Chinese sayings engraved on boulders in the park (“civilized acts make the best landscape”), and the hotel we stayed at in the old mining town of Keketuohai.

If this seems somehow inappropriate, think back to the early years of park development in the United States. Private, commercial concessions were offered enormous opportunities in our parks, and to this day they have enormous political power. The fabled Ahwahnee Lodge in Yosemite, which can cost $1,000 a night, is not owned by Yosemite National Park, but rather by Delaware North Companies. The Old Faithful Inn, one of the most famous log hotels in the world, is not owned by Yellowstone National Park, but rather Xanterra Parks & Resorts.

But wait: Don’t the Kazakhs, who have been living in the Keketuohai valley for centuries, and whose entire culture is based on that particular geography, legitimately own the park? Don’t the Lakota own Rushmore? Don’t the Shoshone own Yellowstone, the Paiute own Yosemite?

On our last day in Keketuohai, before the park decided that they would no longer allow climbing and the border police kicked us out (after first politely getting a lesson in climbing), I struck up a conversation with one of the older, bespectacled, camera-dangling Chinese tourists while riding together in one of the golf-carts. When I explained my surprise that this was a private park, he smiled sagaciously.

“Let me tell you a joke,” the man said. “Chairman Mao is riding in the back of a taxi when the road comes to a T-intersection. The taxi driver asks Chairman Mao which way he should turn, left or right. The taxi is rolling forward, Chairman Mao is thinking, the impasse inevitable. Then Chairman Mao says, ‘Put your blinker on to turn left, but turn right.’”