I met Andre Lambertson less than a year ago in New York. I was on a panel at a leading journalism school talking about work I had done with the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting on HIV/AIDS in Jamaica for VQR and for a website called livehopelove.com. I had come to say a few words and then to be quiet, to listen. But soon I found myself speaking up, trying my best to remind everyone that the lives that we had chronicled in Jamaica were not mere subjects—that these were people and that reporting demands deep empathy. It demands making choices about what questions to ask and what to explore, and most of all it involves a tremendous amount of respect for the people at the center of that work. I did not want to talk, but I had to.

Andre was in the audience. He introduced himself afterward and smiled that intense and embracing smile of his, giving me the knowing look of someone who has had to speak reluctantly before, of someone who has grown weary of having to explain that being involved is a part of what journalists and chroniclers do. By the time we parted, I knew we would work together. We both knew it. We both said it.

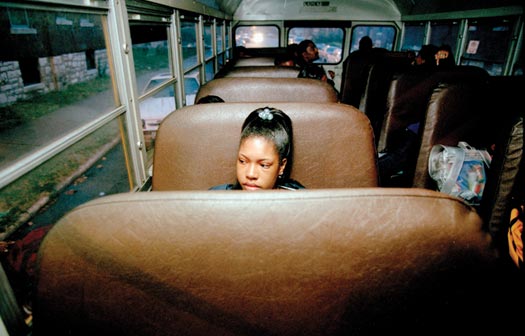

Not long after, Andre got in touch. He wanted me to see some of his work, but he gave me only a slight inkling of what he was sending, and so I was unprepared. The images that I started to open left me with a hollowness in my stomach. The funerals, the bodies, the autopsies, the dingy dark corners where people were shooting up. Andre had also sent me a short film telling the stories of various young people, tracking their lives, giving them a chance to voice their own stories.

I couldn’t help it: these people seemed like clichés, the stereotype. But it had nothing to do with the images; they were alive, filled with deep consuming colors and brilliant framing. It had to do with my feelings, my sense of helplessness, my sense that I was watching a narrative unfold so many times that I could do nothing about, that I could only acknowledge to be truth, and that I wanted to stay far from. That is how I felt. My hopelessness was the cliché.

I wrote to Andre and told him how powerful the images were and how disturbing they were for me. I wondered how he had gotten such access. I wondered how he had managed to get that image of the boy on the mortician’s slab. I wondered about the sounds I could feel behind each image. But I told Andre wasn’t sure that I could write anything. I didn’t want to return to those streets, to those apartments, to those lives.

But the images had already seeped into my mind; they had arrived at the place of haunting, and I could not simply ignore them. I found myself searching for language to exorcise the images from my mind. I was searching for poems to be rid of it all. The first lines came out as a question: “Andre, what have you given me / with these scattered ashes / that fall lightly on my shoulders?”

Looking back, I realize that these were words of anger. I was angry with Andre for making me see into this space. I was angry that children have to eke out joy in the midst of such hopelessness. I was angry at their faces for staying with me. And I was angry at poetry, how small it seemed in the face of all this.

Yet, the poems came—and, as poems do, they worked some things out for me. They turned the images back into what they had been all along: stunning images of beauty but also poignant moments of real people struggling with being human. This is the power of Andre’s photographs: to remind me that these are people not subjects. After that, I found my way through the poems with ease. Not an ease of emotion, but a technical ease. I knew where to focus, what I had to say.

“Ashes” is a blessing—and a benediction. It is a string of elegies. It is a requiem. And, as with all requiems, it is about the living more than the dead.