“I grow more fascinated by Vietnam every day,” Kevin German is saying. “Everything here seems to have a story behind it.” German would know. A son of Port Angeles, Washington, he began visiting Vietnam in 2006, and moved there full-time two years later. Since then, between photo assignments for American and international publications, he’s given himself over to the country. In another year or two, he plans to publish a book of portraits of the nation, tentatively titled In the Footsteps of Ghosts.

“The project examines the economic and social transitions of Vietnam while focusing on the people who are left behind in these changes,” German explains. “After more than three decades, Vietnam is still struggling to recover from the aftermath of the war. But, since joining the WTO in 2007, Vietnam’s economy has been booming. The problem is that the wealth remains in the hands of the rich few. The government is set on becoming a developed nation by 2020, and they will step on any one who gets in their way. The ones left out of this change will be forced into the footsteps of Vietnam’s ghosts.”

As deliberate as German’s project has become, he arrived in Vietnam almost by chance. After graduating from Washington State University in 2003, he worked for six years at various newspapers as a staff photographer. “The last paper I worked for was The Sacramento Bee,” he says. “And I met a woman there who was Vietnamese- American, and I developed this sort of crush on her. She went back to Vietnam for a visit, had a great time, and when she returned and talked about life there, I was really jealous.” Not long after, when another friend told German he was planning to vacation in the Philippines, German decided to go along—and to stop off in Vietnam along the way. His short stay was life-altering. “I fell in love with the place,” he says. “And Vietnam just spoke to me.”

- Thanh quietly looks out the back window of his car while his driver sits in traffic. Thanh is an investor who recently lost several hundred thousand US dollars in the Vietnamese stock market.

German’s life in Vietnam became more permanent when the Vietnamese-American woman in Sacramento decided to move to Saigon and teach English there. German—who’d since become her boyfriend—chose to go, too. He identified six different areas of the country that he wanted to record through photography. “And soon I realized that all six of these subjects were connected to one another by this very fine thread,” he says. “Which is Vietnam itself.”

Camera in hand, he has covered the nation’s length and breadth: from its northern border with China to its southern tip along the Gulf of Thailand. “I get an assignment to go somewhere,” he says, “and then I stay a couple of extra days and do some personal work.”

The resulting images do a stunning job of getting at the soul of the place. Shooting from inside a car, he captures the Brownian frenzy of motorbike traffic in Saigon: the scooters and their riders almost piled up and awaiting the change of a traffic light while, inside the car, the driver is glancing in the rearview mirror. Another passenger stares off impassively. As usual, the photo has its own particulars. “That guy had just lost 60,000 US dollars in the stock market,” German says. “He was very sad. He’d just pulled out the last of his life savings, and the money was in two burlap sacks riding in the car with us. He was a rich man. This was in his private car. It’s a photo about class in Vietnam as much as anything.”

- A construction worker looks out from the top of Vietnam’s first skyscraper in downtown Saigon. The completed financial tower will have sixty-eight stories and a helicopter landing pad.

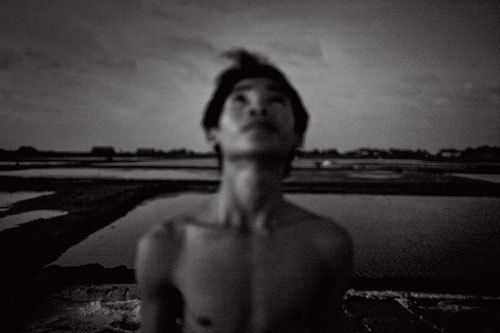

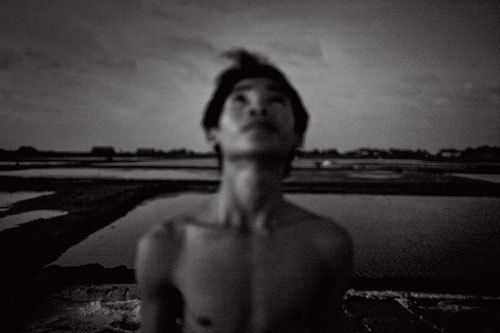

- Phong Quyen, sixteen, takes a break from scraping salt and stares up at the night sky. Farmers harvest salt cultivated in rice-patty-like fields in B n Tre, a village in southern Vietnam.

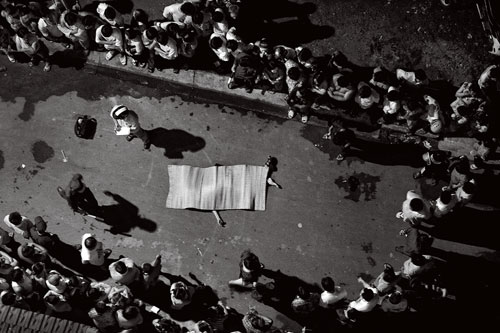

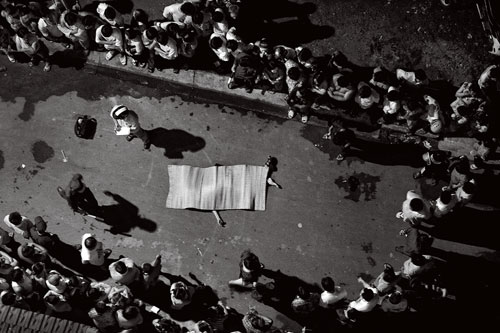

- A poor man spent his last pennies to ride the elevator to the top of apartment building D. Witnesses say he stood on top of the roof just looking down for several minutes before leaping to his death.

Likewise, his portrait of a shirtless rural man in B n Tre captures the breadth of the landscape— the vast salt-harvesting fields of the Mekong River delta behind him—with the horizon lying like a hard-drawn line far, far in the distance. But the image also captures the despair of the province, where thousands of salt workers have been cast into poverty by plummeting salt prices—brought on by the importation of cheaper foreign salt by the newly globalized government. Helpless farmers spend days bent in the burning sun, but their nights are filled with worry. “That photo was lit by moonlight,” German says.

German’s views of Vietnam sit in sharp contrast to the claustrophobic, black-and-white news images of a nation most Americans recall from the Cronkite era. They accurately document the country’s huge landscape, sprawling across seacoasts and enormous fields and conical mountains, where water buffalo are still used for the heavy work on farms, but they also show office towers rising in the cities as fast as the I-beams and conduit go in.

“Vietnam is developing at an incredible rate,” German says. “And the juxtaposition between rich and poor, as in any country, is huge. Here, with 80 percent of the people still living as rural poor while skyscrapers and cell phone towers wash across the landscape? There are amazing stories in that.”

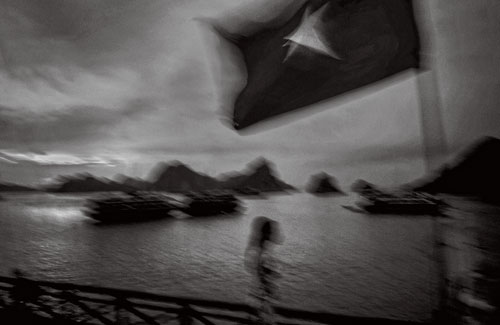

In one particular grainy frame, he captures a handful of karst limestone batholiths jutting from the seas of Ha Long Bay, with a hazy woman and the nation’s single-star national flag in the foreground like bookends. The image was taken on a tourist boat out in the bay, one of many cruises aimed at capitalizing on the natural beauty of the UNESCO World Heritage Site. It’s gauzy and placidly moody and beautiful. Yet it also bespeaks the growing commercialism that threatens Vietnam’s very core.

Nearly all of German’s Vietnam portraits seem to embody these kinds of contrasts and contradictions. “When I think of the photos I’ve taken so far, I’m always drawn to the one of the kid jumping into the river,” German says. “It was taken on a tributary of the Mekong. There’s garbage in the water—pollution—but the kid is jumping in and loving it.” It’s a moment of pure joy, of playfulness.

- Dozens of “saved” children roam the halls of an orphanage outside of Nha Trang. Their mothers were talked out of abortions but they did not want to keep them.

German says he likes to juxtapose the bellyflop photo with another image, which he calls “Death at Building D.” That image was taken from his own apartment block in Ho Chi Minh City. “I was still pretty new there,” he says. “I was worried about how the police might react to someone shooting pictures of this scene. So I shot a couple of images from the third floor. Then I went up to what I think was the sixth floor, which was dark. Nobody could see me.” The person at the center of the image was a homeless man who lived on the street near German’s apartment complex. “The kids on the street used to make fun of him,” German says. “Nobody knew his name. Everyone called him ‘The Poor Man.’ Anyway, he used his last 1,000 Dong, which was about 16 cents at the time, to buy a ticket to ride the to the top of the building in the elevator. If you don’t live in the building, you have to buy a ticket to use the elevator. When he got to the top, he stepped off and fell into the street. He landed in this strange position. They covered him up.” The image stands in stark contrast to the joyful children on the bridge—perhaps some of whom taunted the poor man—but it shows us one of the many ghosts German sees in the newly emerging Vietnam.

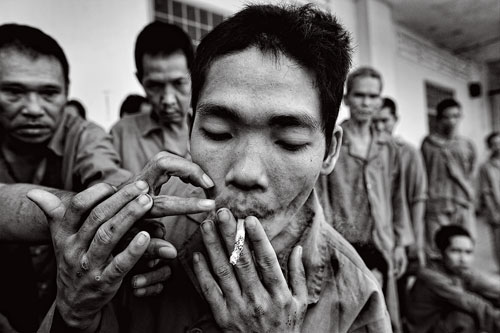

Such apparitions are all around at a mental hospital in My Tho that he has visited often as part of a portfolio about mental health. One day when he was there, several of the patients began struggling and fighting over a cigarette. “They all wanted the last puff,” German says. “I love all the hands coming into the frame. But my favorite part of that photo is that I’d been visiting that hospital regularly for some time, and they would never let me shoot. And then, one day, they just welcomed me in and left me alone there. And I began shooting. That’s Vietnam.”

Donovan Webster is the author of several books, including Aftermath: The Remnants of War and Meeting the Family: One Man’s Journey Through His Human Ancestry.