Perched atop the Moqattam Cliffs, where Pharaonic slaves cut limestone for the pyramids, the Monastery of Saint Simon and its accompanying cathedral boast a commanding view of Cairo. On a smog free day, if you peek around the cliffs to the south, you can see clear to the Great Pyramids of Giza. Looking west, you have a fine view of more recent history; you can almost throw a rock at the Citadel of Salah Ed-Din or into the endless expanse of tombs that make up el-Arafa—the City of the Dead. On the western horizon, the Cairo Tower stands apart from the deceptively modern skyline of downtown. Right below your feet, largely invisible to the outside world, you’ll find Izbet Az-Zabaleen. The Garbage City, as it’s known in English, is a hive of entrepreneurial recyclers called zabaleen, literally “garbage people,” nestled at the edge of Manshiet Nasser, a teeming slum on Cairo’s eastern outskirts. A haze produced by the exhalations of some 2,500 black-market recycling workshops carpets a landscape of windowless brick high-rises and unpaved alleys piled high with garbage, the raw material of zabaleen industry. Rooftops serve as storage for stockpiles of plastic bottles, but also for herds of sheep and pigeon coops.

Women cluster in the trash-lined dirt streets, sorting organic waste from recyclables. They hunt for aluminum, tin, steel, and sixteen types of plastic—from the kind used to make Ziploc Baggies to the crash-resistant stuff of car fenders. Bands of barefoot children play amid the waste. To the uninitiated, the scene appears downright infernal—like the fiery orc workshops of The Lord of the Rings. But looks are deceiving; the zabaleen swear they’re living better than ever.

In sixty years, the zabaleen have gone from serfs to recycling entrepreneurs. Palaces have risen from the trash, bricks purchased bottle by bottle. There are real-life garbage kings in the village with informal businesses worth millions of dollars, but most of the 60,000 zabaleen in the Garbage City live modest lives defined by hard labor and strong family obligations. They and others like them throughout the city collect an estimated 4,500 tons of garbage from Cairo and Giza each day, and they claim to turn 80 percent of everything they collect into post-waste, saleable materials. By comparison, Switzerland—which claims to have the best-organized recycling program in the world—recycles just over 50 percent of its waste.

Almost all zabaleen are Coptic Christians whose families migrated to Cairo from Upper Egypt (the country’s agricultural south, called “upper” because it’s upstream from Cairo) in the 1940s, when government land reforms brought down a centuries-old feudal system and forced tens of thousands of peasant farmers into the cash economy. Like their Muslim compatriots, Coptic zabaleen remain deeply religious. Family homes are plastered with icons and biblical quotations, and the monastery above the Garbage City is the zabaleen’s private paradise. Hundreds of people stream up the hill in the afternoons to visit the gardens and breathe the comparatively clean air. For thousands of zabaleen women who rarely leave the Garbage City, Saint Simon is the only sanctuary from a life lived among the refuse of sixteen million.

Moussa Zikri and I are admiring the view from Saint Simon one afternoon when his phone rings. His face goes gray as he listens to the voice on the other end. When he hangs up, he asks politely if we can leave.

“What’s wrong?” I ask.

“There is a fire at my dad’s work,” he says. “I have to go there now.”

We begin walking briskly downhill.

“Do you want to run?” I ask.

“Yes,” he says, and he takes off.

I sprint too, past girls on their way up to the monastery who giggle as we run by, past men hunched under ridiculously large sacks of garbage. We pick our way around donkey carts, squished rats, and puddles filled with sludge. Moussa flags down a car at the bottom of the hill. I walk the remaining distance, orienting myself toward a growing plume of black smoke. When I arrive, I find Moussa panting before a flaming heap of plastic bottles.”My materials!” he shrieks.

Moussa’s father works as a guard at a parking lot where garbage collectors keep their trucks when they’re not working. Moussa, twenty-three, is the youngest of three brothers. He recently got into the bottle recycling business with the help of a $2,000 microloan, and he stockpiles his bottles in the parking lot where his dad can keep an eye on them. Somehow a fire sprung up this afternoon and it’s consuming weeks of work right before his eyes.

Moussa’s little sister brings pails filled from a hose, and his brothers sling the water over the flames. The fire hisses and pops, mocking their efforts. Finally, firemen arrive and unleash a blast of high-pressure water from their fire engine. In minutes, Moussa’s mountain of bottles has been reduced to a steaming slagheap.

Moussa and Samaan, his older brother and partner in the bottle recycling business, rush up the street to buy a bundle of giant woven sacks made from recycled grain bags to gather the surviving bottles. They salvage enough to load a Datsun pickup to three times my height, but Moussa remains inconsolable.

“Today is a big misfortune for me,” he says. “I probably lost eight hundred kilos today.” Moussa travels all over Cairo to buy bottles from garbage collectors spread throughout the city. He hoards bottles with his own capital, then turns a small profit by shredding them into chips and reselling them to an exporter.

Moussa estimates the fire damages at about thirty dollars—a seventh of his monthly income. He’s sure the firemen would have arrived sooner if the address were somewhere other than the Garbage City. Manshiet Nasser is an “informal” development, in the language of Egypt’s Ministry of Planning; Moussa and his family are technically squatters, and they and the other zabaleen receive little in the way of government services.

I follow Moussa upstairs to his living room after he and Samaan finish unloading the unburned stock into their basement. The doorframes and walls are coated in black grime. A ceiling fan casts a choppy shadow over the room. Samaan’s one-year-old son Abanoub stumbles around behind his mother screaming bloody murder. He was circumcised the day before and has developed an infection. Abanoub’s mother paces around frantically, clutching the phone and begging Samaan to call the doctor.

Moussa’s two-year-old nephew waddles into the room with a Styrofoam plate of potato chips. He trips and spills the chips on the floor at Moussa’s feet.

Moussa bends over to pick up a chip from the floor. He crunches it in his mouth, and a fleeting grin appears beneath his glazed eyes.

“I’m going crazy,” he says.

Today’s zabaleen were preceded by a group of garbage workers called the wahaya, or “oasis people,” who emigrated to Cairo from Saharan waterholes in the early twentieth century. The wahaya made money by gathering waste paper and selling it to public bathhouses in downtown Cairo, where it was used to heat bathwater. The government eventually prohibited the use of waste paper fuel in public baths, and the wahaya had to find a new business model.

In came the first waves of Coptic farmers from Upper Egypt. They struck a deal with the wahaya: they would collect the garbage and use it to raise pigs, and the wahaya would keep the rights to garbage collection routes and monthly collection fees charged to residents. The wahaya would provide each Copt family with a pigsty and two pigs to get them started, and the Copts could buy out their pigsties over time.

In the 1940s, the first zabaleen neighborhoods sprouted in Torah and Imbaba, two greater Cairo areas that were once on the outskirts of the city but have since been enveloped in the city’s endless sprawl. The Giza Governorate forced the zabaleen out of Imbaba in the seventies and many families relocated to the arid and inhospitable desert below the Moqattam Cliffs.

The wahaya no longer collect garbage, but they guard their roles as middlemen between the trash and the profits. They still control the garbage collection routes and take a three-fifths cut of all collection fees. The trade-off between zabaleen and wahaya remains essentially the same: zabaleen families keep all the garbage they want; only now, instead of feeding it to pigs, they mine it for recyclable materials.

Sherif, the collector who worked my building with his brother and nephew in May and June 2010, paid the wahaya with rights to my neighborhood about sixty cents out of the dollar he collected monthly from each of the 250 apartments on his route. Sherif’s three-man team thus earned around a hundred dollars per month from collecting six hours a day, six days a week. The bulk of their monthly income came from selling plastic bottles to shredders like Moussa.

In 1983, the Cairo and Giza Cleansing and Beautification Authorities (CCBA, GCBA) divvied up collection routes between the biggest wahaya families and gave them legal recognition, but the zabaleen missed out on the deal. Their livelihood remains technically illegal, and they often pay petty bribes to street cops to avoid fines for using donkey carts in the city and driving trucks overloaded with garbage. Rather than draw more attention to their community by agitating for a more equitable system, the zabaleen try to fly below the radar.

In June 2009, the zabaleen took the biggest hit to their livelihood in history: in a panic over the spread of H1N1 “Swine Flu,” which had yet to reach Egypt, the government slaughtered 300,000 pigs belonging to zabaleen families. The pig cull struck the zabaleen as a personal assault. Many Copts believe they are the de-facto scapegoats whenever Egypt runs into problems, and they suspect the government of killing the pigs to appease Muslims whipped into a frenzy by the H1N1 scare.

Pig farming had been the core of zabaleen’s business since they began their relationship with the wahaya in the 1940s. The zabaleen were so well known for their pigs that many Cairenes referred to their neighborhoods as “zarayyib”—pigsties. The pigs were a vital organ in the system; they sorted organic garbage from the recyclable materials with their mouths, allowing the zabaleen to profit from the garbage in three ways: by selling pork to fellow Christians at market, by selling truckloads of manure to rural farmers as fertilizer, and by selling recyclable materials to workshops in the Garbage City. Families took fattened pigs to market every six months, and a dozen hogs could generate as much as fifteen hundred dollars of supplemental income. “The use of pigs was very clever,” explained Nicole Assad, who has volunteered in the Garbage City for nearly thirty years with the Association for the Protection of the Environment (APE). “The pig is the only animal we know that can consume such quantities of organic garbage—thirty-two kilos a day.” When the pigs vanished, it was as if the zabaleen machine suddenly had to run without an engine.

A forty-three-year-old mother of six named Naema—who, like many women in the Garbage City, spends her days sorting the garbage her husband brings home at night—told me that the worst consequence of the pig slaughter is that they can no longer handle as much trash. “We used to have two hundred pigs, and now the pigsty is overflowing with trash. We can’t keep up.” Absent hundreds of voracious mouths, the sorting process takes much longer—and produces fewer recyclables. “We want the pigs back,” another woman told me. “It was a perfect system: they ate the garbage, and we ate them.”

As they adapt to a hog-free world, the zabaleen have to contend with another roadblock: the arrival of multinational waste management consortiums. In 2003, in an attempt to modernize the capital, the Egyptian government invited corporations to bid on multimillion-dollar contracts for the collection and disposal of Cairo’s garbage. When green-suited waste workers hit the streets with their compaction trucks and dumpsters, the zabaleen feared their days were numbered.

But Cairo itself seemed to come to their defense. Much of the city—from the ancient Fatimid arcades to the modern slums—rose around narrow alleys meant for foot traffic and donkey carts, not for cars or trash trucks. Even in modern Zamalek, where I stayed, most streets allow for the passage of only a single car between rows of cars parked two-deep along the sidewalks. On the wider axes, paralytic traffic makes a grueling slog out of the shortest journeys. Before long, the multinationals were up to their ears in trash, utterly overwhelmed by Cairo’s garbage.

Logistics were not the multinationals’ only problem. They were also unable to convince Cairenes—accustomed to leaving their trash at their apartment doors for the zabal—to carry their trash bags down to dumpsters each day. In many locations where residents brought trash out to curbside bins, corporate garbage trucks failed to pick it up frequently enough, and the dumpsters overflowed. Dumpsters became feeding troughs for cats, dogs, rats, and weasels. The populace grew indignant.

Cairenes were also infuriated by the government’s decision to charge them for trash collection directly on their utility bills. Suddenly, they were paying twice—one payment to the multinationals, and another payment at the door for the people who actually collected the trash: the zabaleen.

To learn how multinationals were coping with their dilemma, I make an appointment with Ahmed Nabil, General Manager of International Environmental Services (IES), in his glass and steel office next to the American Embassy. IES won a $6.5 million annual contract to collect waste from Giza, but after six years on the ground the company still pays huge sums in fines for repeatedly failing to empty dumpsters on time. The fines have hobbled IES and prevented them from expanding their fleet or offering more jobs to the city’s legions of unemployed. (Nabil would not disclose a figure, but Luigi Pirandello—the Italian manager of another multinational firm called AMA Egypt—told me his company pays 7 percent of its revenue in fines.)

After bemoaning myriad forms of GCBA harassment and waxing nostalgic about his sojourn in Houston as a young engineer, Nabil—wiry, with a thin silver mustache and a raspy smoker’s voice—turns to the zabaleen. He sips his double espresso and tamps out his fifth cigarette, folding the filter neatly over the ember and pressing down with his thumb. “Of course the zabaleen are part of the plan,” he says. “From the social point of view, we have a responsibility to keep them working, and from the point of view of experience, they can do what no one else can. The question now is how should they be integrated?”

When the multinationals first arrived, they attempted to hire zabaleen as collectors at about sixty dollars a month, the going rate at the time for manual labor in Cairo. The zabaleen never showed much interest, partly because working for them would be seen as betrayal of the community—like a scab breaking a strike line—but more because the zabaleen recoil at the idea of simple wage labor.

“The zabaleen are business people in their own right,” explained Bertie Shaker, a researcher with CID Consulting, a Copt-owned firm that has advised the government and the multinationals. “They don’t want to be beholden to corporate interests, or to turn over the methods and expertise they’ve spent generations developing in exchange for a wage.”

Executives like Nabil have a strong financial interest in co-opting the zabaleen: illegal dumping by zabaleen is the main source of multinationals’ fines. The problem spun out of control after the May 2009 pig cull. For the zabaleen, dumping was partially an instrument of revenge. Mountains of trash shot skyward from vacant lots across the capital, and multinationals took months to get the situation under control.

Nabil hopes to discourage illegal dumping by bringing the assets of his company and the zabaleen in line. By contract, IES must recycle 20 percent of all garbage collected, a mark the company has never met. Nabil thinks the zabaleen could help his company reach the bar, and he plans to scratch their backs in return. He has advocated the construction of a transfer facility the zabaleen could use instead of an illegal dump site to sort recyclables from organic waste. The zabaleen could cart off all the recyclables they could manage, and IES could truck the organic waste left behind to composting facilities, where it could be turned into environmentally safe fertilizer for donation to rural farmers and counted toward IES’s recycling percentage.

“If they dump garbage on the street, we incur more expenses to collect it, but if there was a place where they could come and sort in a hygienic plant, they could double or even triple their efficiency,” Nabil says. “To waste their experience is wrong. To use their experience is a win-win situation.”

It’s just after eight on a May morning, and Moussa and Samaan are preparing for a long day at the shredder with taamiya sandwiches and tea at a hole-in-the-wall coffee shop down the street from their house. Today, the machine under Moussa’s house will eat 1,700 pounds of plastic soda bottles. Baba Shenouda, the Coptic Pope, drones from a fuzzy TV mounted in a corner. Moussa puffs on a gurgling waterpipe and hums along to the liturgy. One of the Zikris’ friends, a guy named Beshoul, takes it upon himself to introduce me to everyone in the shop. This is so and so, he works with PET plastic, he says, and this is so and so, he works with cardboard. Every zabaleen recycler has a specialty—they are master guildsmen of trash.

Back at the house, Moussa and Samaan hoist open the corrugated iron door to their garage. Sunlight sends rats scurrying into the shadows. We scramble over filthy bags of bottles stacked to the ceiling to get to the back of the garage, where the shredder is plugged into a high-voltage socket. Wedged into a corner, we’re completely walled-in by a fortress of eight-foot-tall bags stuffed with bottles. All that plastic does little to dampen the agonizing whine of the circular grinder Samaan uses to sharpen the shredder blades. I put on my sunglasses to protect my eyes from the bursting sparks, but Samaan just squints scornfully and keeps grinding.

The men work with astonishing speed. Their shredder consumes each giant bag of bottles in about five minutes, and little by little the magic machine chews its way out of the hole. Like Rumplestiltskin spinning a heap of straw into gold, these men are turning worthless bottles into cash. After awhile the machine gets hot and begins to put off bitter fumes, a mix of diesel exhaust and vaporized plastic. There’s no ventilation except for the open garage door. Moussa tries to hide his running eyes from the smoke rising from the mouth of the machine. Veins bulge from his thin arms as he plunges bottles into the blades with a giant Aquafina jug. Samaan fills the hopper and shovels the growing pile of chips. He hangs empty bags by a nail driven through an icon of the Virgin Mary.

At some point Samaan passes me cotton balls to stuff in my ears, but the damage is done. For the rest of the day, I feel like I’m underwater. We take a break at noon and head to the coffee shop for a smoke. We wade through a two-foot layer of 7-Up and Sprite bottles to get out of the garage—it feels and sounds exactly like wading through the balls at a McDonald’s PlayPlace. We stop to say hello to Moussa’s mother and father, who are squatting in a garage across the street, sorting plastic shopping bags into color-segregated bins. A donkey is tethered to a post next to where they’re sitting and chickens are pecking at the dusty floor.

Three giggling boys pile around the table where Moussa and I are sitting at the coffee shop. Their names are Samaan, Abanoub, and Gergis—names as common to Copts as Mohammed, Ahmed, and Mustapha are to Muslims. Moussa arm-wrestles with the boys, who clearly admire him. He’s a hotshot among the younger generation of zabaleen, with his microloan and his progress in the Recycling School, a non-profit established to reach out to zabaleen kids left behind by the formal education system.

Samaan sits alone in a corner of the coffee shop, scowling. His relationship with Moussa is frayed, but I haven’t found out why. We pay and go back to Moussa’s house, where his sister-in-law has prepared a lunch of chicken and stewed tomatoes. We pick hunks of meat off the chicken with pieces of flatbread. Moussa and Samaan don’t speak a word to each other, but Moussa’s sister-in-law is more relaxed today now that Abanoub’s infection has passed. She sits with us and laughs at my Palestinian-accented Arabic. Samaan, suddenly in a foul temper, sucks the joy from the room. He snarls at the kids whenever they stray too close.

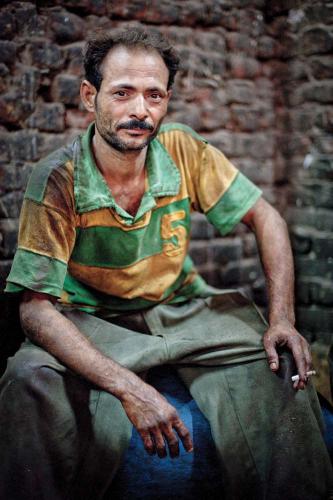

After lunch Moussa takes me to visit his English tutor, a thirty-two-year-old bachelor named Rizeq Youssef. We find him at a table on the street in front of his grandmother’s house at the edge of the Garbage City, where the zabaleen’s realm butts up against the vast Muslim slums. We wait for Riz, as Moussa calls him, to wrap up a business deal on his mobile. Riz runs a bustling PET-chip exporting business—PET is the variety of plastic used to make soda bottles—and the café next to his grandmother’s place is the closest thing he has to an office.

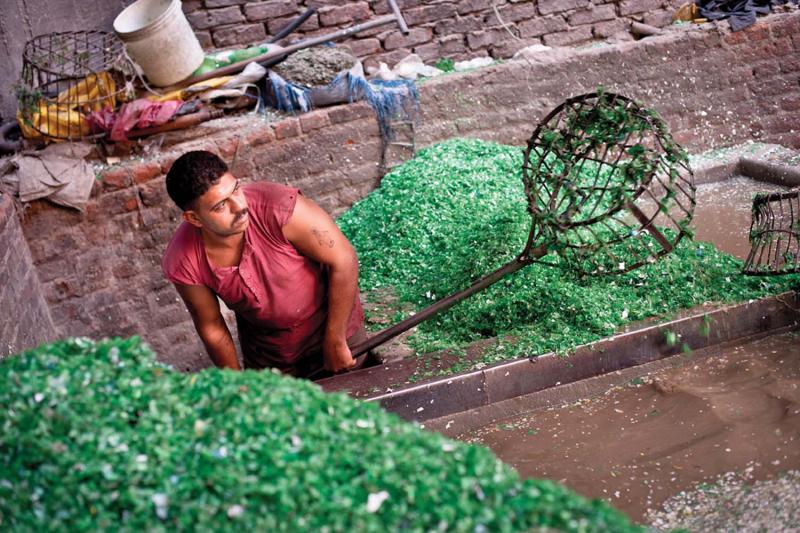

As we wait, Riz’s workers unload grain sacks full of unwashed green plastic chips from a truck. Each sack weighs about eighty pounds, and there must be thirty of them. Riz has just purchased the chips from a shredder, and now his workers will wash the chips in a series of vats to remove debris and remnants of labels. Then they’ll dry the chips in the sun and repackage them for shipment to China.

Riz is tall with graying hair, a mustache, and a pocked, chubby face. He got into the PET business about ten years ago, and he’s got his operation down to a science. He exports one ton of chips to China for a total cost of about $515, including labor and shipping expenses. He exports forty to sixty tons of PET each month to Chinese importers, who re-sell the chips to textile manufacturers at a 20 percent markup. Riz splits the profit with the importers. The real value enters when Chinese manufacturers turn the chips into polyester, which eventually makes its way to American shopping malls in the form of tracksuits and sneakers.

Riz’s business only works on an economy of scale. He buys chips from dozens of shredders, including Moussa, and deals in huge volumes. He employs seven men and runs his washing workshop six days a week. “I’m happy if I make fifty dollars per ton,” he says. At fifty dollars a ton and sixty tons a month, Riz earns about $36,000 a year. Hardly a king’s ransom, but he has ambitions. He’s saving to buy a machine that will help him increase his output to fifteen tons daily, putting him into serious cash.

Riz considers himself extremely lucky. His father was a science teacher at a government school who went out on a garbage collection route on the weekends, and his mother worked as a garbage sorter. His parents scrimped to send him to the private Gabbal Moqattam School, founded in 1981 by a Belgian nun named Sister Emanuelle. There were no schools at all in the Garbage City prior to the opening of Gabbal Moqattam, and Riz was one of the first enrolled students. Today, he is one of the school’s most celebrated graduates.

Riz went on to get a university teaching degree and become a teacher, “but I was always working both jobs,” he said, and “my business was suffering. I like teaching, but I think my mind is more suited to business.” Still, Riz can’t shake a sense of community obligation, so he spends his free time outside his grandmother’s house writing down English vocabulary for neighborhood kids and coaching them through their homework. As we talk, Moussa plucks words out of our conversation and scrawls them out in shaky English letters in his notebook. Riz pauses occasionally to correct him.

Moussa listens with wonderment as Riz rattles off calculations, so many tons of chips form the shredders equals so much profit from China. If Moussa keeps working and studying, he could develop a business like Riz’s someday. As we walk back from Riz’s in the dwindling sunlight of early evening, however, Moussa grows sullen. I quickly understand why. When we arrive at his street, Samaan comes flying out of the coffee shop in a rage.

“Where were you!” he screams. “I’ve been calling you all afternoon!”

Moussa had taken off after lunch to visit Riz and left Samaan alone to contend with a sea of bottles.

“My battery died! Besides, I told you I had a lesson today,” Moussa growls. Samaan throws up his hands and storms off. Moussa and I keep walking toward the highway, where I’ll catch a taxi home.

“Sometimes when I’m alone,” he says, “I write my whole life down. I ask myself, what can I do with my life? Can I live outside? Maybe I can leave Egypt. I am tired of this life. I am tired of carrying my whole family.”

He mumbles something.

“What did you say?” I ask.

“Ar-rab yesouah aarib min i-khaifeen.”

The Lord Jesus is close to the afraid.

Ezzat Naem has come a long way since his childhood years, when he spent his days sorting garbage with his parents. Now he’s director of the Spirit of Youth Association, which oversees the Recycling School for Boys. “Children’s education is the first thing to go during economic hardships,” Ezzat told me. A successful girls’ school program founded by the Association for the Protection of the Environment in the 1980s, centered on crafts projects and literacy, paved the way for the Recycling School, which now has a hundred and fifty boys enrolled.

Moussa is the equivalent of an eighth grader at the Recycling School, which focuses on literacy and arithmetic while striving to harness students’ entrepreneurial zeal. There is no telling how sophisticated young zabaleen could become with strong foundations in mathematics and market analysis. Like most boys of his generation, Moussa never received any formal education before starting at the Recycling School at age sixteen. Government schools in Manshiet Nasser average sixty students per classroom, and the overcrowding deprives students of individual attention. Parents pay for after-school private lessons in order for their kids to pass yearly exams. But lessons cost nearly two hundred dollars per year and Zabaleen kids are also sorely missed during the workday, when they care for siblings and help process garbage.

In order to convince parents to send their kids to school, teachers had to show that students could still contribute to family income. Students at the APE girls’ school received a dollar per day for the weaving work they did between lessons, and upon graduation they received a loom in their home and free rug making material. The school would then buy the girls’ woven products and sell them to wealthy Egyptians. The girls’ school is now in its thirtieth year, and the Recycling School hopes to emulate its success.About half of the boys enrolled at the Recycling School earn money by gathering, weighing, and destroying shampoo and conditioner bottles. Proctor and Gamble funds the school as part of its Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) regimen, but also because they were losing tens of thousands of dollars to counterfeiters who used to buy stockpiles of bottles, re-fill them, then sell them on the street. Since the Recycling School opened in 2004, its boys have destroyed 250,000 bottles.

I visited Moussa at school one day and found him sitting at a low table with two students about his age and two little boys who were about twelve. The walls were painted in exuberant purples and pinks and the ceilings were strung with shampoo bottle craftwork. The room had the feel of a kindergarten, and a fair number of the boys in the room looked about kindergarten age. They were the lucky ones, to have such an early jump on education.

Moussa was taking down dictation in Arabic from a young female teacher. At another table, little boys worked math problems with an abacus. Moussa didn’t seem worried that his classmates were less than half his age. He lives and breathes the Recycling School. He is studying hard for an exam that will allow him to matriculate to high school, and he would probably live at the school if they’d let him.

“Moussa can make it if he believes in himself,” said Ezzat Naem, another one of Moussa’s heroes. It was Ezzat and the staff of the Recycling School who helped arrange Moussa’s microloan. “He snatches at opportunities. He’s hungry for chances and willing to work hard. If he is ambitious enough, he can do anything.”

Mariam Abdel Malik must have been expecting me to arrive at the Ministry of Planning with an entire television crew. She had a dozen plates of cookies set out on the giant conference table, and I think she was disappointed when she realized I had come alone. I had come to the Ministry of Planning to glean their plans for the future of the Garbage Village and the rest of Manshiet Nasser, and Mariam was going to be my guide.

There is a lot of anxiety in the Garbage City about the possibility of a forthcoming eviction, and a lot of historical evidence to suggest it might happen.

Ezzat Naem singled out real estate developers—not multinational waste management firms—as the greatest threat to the zabaleen community. He fears the government will force the zabaleen from Garbage City just like they were forced out of Imbaba forty years ago. They survived the previous eviction, but it’s different now. Back then, zabaleen lived in shacks and owned only the clothes on their backs and their pigs. Now they live in a city they’re proud of, that they’ve built with their own hands and the sweat and ingenuity of generations. “The house is the primary investment and the primary site of business,” Ezzat told me. “You can’t do this work from an apartment. It just doesn’t work. Families need their garages to store materials and to keep their machines.”

I keep Ezzat’s anxiety in mind as Mariam, a middle-class Egyptian who happens to be Christian, leads me through a PowerPoint on the Greater Cairo 2050 Master Plan. “Seventy-five percent of the population of Cairo lives within a twenty-kilometer diameter,” she tells me. “The population density is extreme, and the purpose of the plan is to decentralize Cairo to reduce population density.”

Illustrations flit across the screen of a place that looks like Orlando, not the traffic-choked, polluted mess outside the ministry’s doors. Leafy trees line wide boulevards devoid of people and cars, and aerial sketches show swathes of jungle canopy over much of the city’s slums. The few cars there are conspicuously observe the limits of their lanes—the surest sign that these images are from a fantasy Egypt.

When Mariam comes to a slide of a giraffe bending down to lick an ice cream cone held out by a blonde woman in a sports car in the middle of the desert, a ministry employee named Nahed deadpans, “Now this is the future.”

“Yes, this is too much,” Mariam laughs.

I ask Mariam to return to a slide diagramming Cairo’s residential areas according to three status labels: planned, unsafe, and unplanned. Part of the Master Plan, as Mariam explained, is to relocate everyone living in unsafe and unplanned areas to new satellite cities in the desert. The government will demolish the slums—including large portions of the historic City of the Dead, where an estimated 25,000 squatters have turned tombs into homes—and attempt to bring back the expansive green spaces that existed in Cairo’s Nile watershed just twenty years ago.

“We will build new apartments in unpopulated areas for the people in unsafe areas who are to be relocated,” she says. Unsafe areas include areas under power lines, areas where access streets are not wide enough to permit emergency vehicles, flood prone areas, and areas under cliffs. Those conditions describe almost all of Cairo’s most crowded downtown neighborhoods, as well as large areas of Giza, including the slums that abut the Great Pyramids.

The entire Moqattam area is unsafe in at least two of those categories—it’s on the cliffs, and its tiny alleys would be all but impossible for an ambulance driver to navigate. I was on-hand two years ago when a rockslide in the Duweiqa neighborhood next to the Garbage City killed over a hundred people. In this instance, the rockslide happened at a place that was easy for ambulances and fire trucks to access, but it didn’t matter. It took days for the Egyptian rescue services to finally admit that they had no idea how to break apart the giant boulders to unearth those buried beneath. The most tragic aspect of the disaster was that the government had finished construction several years before on hundreds of new apartments for families living under and above the Duweiqa cliffs, but had never distributed them. Rumors surfaced after the rockslide that the bureaucrat in charge of placing at-risk families in the new apartments sold them to his friends instead.

As Mariam tells me about the relocation plans and shows me mockups of the Disney-esque Future World the government will build for Cairo’s poor, I think of the giant boulders on top of crushed Duweiqa homes and the lines of riot police. Not in another forty or a hundred years could I imagine a relocation project on the scale Mariam is describing. If the government won’t invest in proper schools and hospitals for the poor, why would it hand them the keys to a new city?

I inquire directly about the ministry’s plans for Manshiet Nasser. “Unsafe areas will be khalas,” Mariam says, wiping off an imaginary slate. “They will have a choice between an apartment or money.”

“So there will be no people living here in 2050?” I ask, pointing to the Garbage City on the map.

“No.”

If you hang around the Garbage City long enough, you start to think that things aren’t so bad. You give up trying to keep your shoes clean and you stop worrying about where you sit or the fact that no matter how many times you clean your fingernails, they’re always lined with black. After awhile, you don’t think about it when you shake someone’s hand who has just had their arm elbow-deep in trash. You leave your Purell at home.

And if you listen to the older zabaleen, you start to think the younger generation has it pretty good. A stout, perpetually smiling mother of five who went by the name Um Michael told me, “When I was a kid there were no schools. There were not even any houses! We used to live in wood and tin one-level shacks right next to the pigs. We even used to go to the bathroom in the pigsty.” Um Michael was born in 1968 in Imbaba. She said life has gotten much easier for women in particular. “Twenty years ago we couldn’t even leave the house!” she said.

The zabaleen are Christians, but they’re still rural Egyptians and cling to the same conservative social practices as their Muslim counterparts; until this century, female circumcision was widespread in the Garbage City (it has nearly been eliminated thanks to NGO activism), and widespread adherence to traditional Egyptian codes regarding the protection of feminine virtue—observed by Muslims and Christians—prevented women from working outside the home in any capacity.

After puberty, women’s lives were restricted almost exclusively to domestic work and child rearing. “There was no education at all for girls,” Um Michael said. Now forty-two, she is taking literacy classes at Saint Simon and has attained an eighth grade reading level. She is immensely proud. In a living room scrawled with biblical graffiti, she fed me watermelon and pungent aged cheese that masked the smell of the streets outside. “I’m sorry the house is so dirty,” she said. “It’s not usually like this, but I’ve been studying so hard I haven’t had time to clean.”

Marianne Marzouk, Um Michael’s oldest daughter, lives a life that Um Michael never could’ve imagined as a young woman. Marianne has a university degree, speaks English, and recently got a loan to start her own business. It’ll just be a small clothing shop underneath her house, but her decision to quit her pharmacy job and strike out on her own shows that entrepreneurial spirit is not limited to zabaleen men alone. It’s also notable that Marianne, at twenty-two, is not already married with children; young men and women from the zabaleen community are waiting longer to marry and having fewer kids, allowing them to pursue their work and educational interests with greater freedom.

Many younger zabaleen have visited relatives in their ancestral farming villages, and they are happy to leave the clean air and green vistas behind to return to the Garbage City. “I went with my father once to Assiut,” Moussa told me. “There was nothing to do, and I asked my father if I could come home early. I hated it!” Naema came north to be married as a teenager and has never looked back. “In the village the men work all day under the burning sun for two dollars. They don’t own the land and there is no opportunity,” she explained. “Here the men can work as much or as little as they please. The amount of money they make depends on how hard they work.”

In so many ways, a brighter future has already arrived for the zabaleen. They have achieved most of the improvements in their community through their own cooperative labor and ingenuity. All they ask now is for the freedom to continue improving their community at their own pace without government interference in the form of aggressive regulations or, in the worst case, forced relocation.

I was surprised to learn that Ezzat supports Ahmed Nabil’s idea for transfer facilities where zabaleen can turn over organic waste to the multinationals and sort their recyclables outside the Garbage City. “If we can convince the government that we are the experts with garbage and recycling, and they help us upgrade our systems and our technology, then our living conditions will improve immensely,” he said. Rizeq Youssef said he is already planning to move his washing operation out of the Garbage Village once the government makes industrial land available. “There are many people looking to buy land,” Rizeq said. “I’m trying to invest in land too, because I need space to make my business bigger.”

Dr. Atwa Hussein, a soft-spoken Ministry of Environment employee with olive green eyes and a neat desk, does not conform to my idea of a scheming bureaucrat. In his office near Cairo’s old city, he told me that the government has plans construct two sorting facilities in the desert surrounding Cairo exactly like the one Ahmed Nabil described. “The biggest problem from the Ministry of Environment’s point of view is informal dumping and the accumulation of garbage,” he said. Informal dumps are more than eyesores—they catch on fire and pose a serious threat to adjacent areas, and they also exude methane and pollute the water table. Informal dumps are also factories for disease, especially when located close to overpopulated megacities like Cairo.

Dr. Hussein admitted that the government rushed into reckless contracts with the multinationals in 2003, and that new contracts should account for the zabaleen, who Dr. Hussein sees as Cairo’s most important waste management asset. His office is re-working waste management contracts to shift to a service by ton model—a shift they believe will lead to a cleaner Cairo and a more productive relationship between the government, the multinationals, and the zabaleen. “Service by route and pickup times does not incentivize the companies,” he explained. “A service by ton model will mean that companies will get paid to work as much as they can.” As for the zabaleen, “In the new contracts we will make it possible for the zabaleen to work officially as subcontractors for the multinationals. They will get paid a rate per ton of garbage they take to the sorting facility multiplied by the kilometers driven from the pickup point to the facility.”

Zabaleen collectors with whom I spoke said multinationals already allow them to dump organic waste in their trucks at night, and some even said the multinationals pay the wahaya to organize transfers. Where many parties see a hopelessly complex set of competing interests, Dr. Hussein sees an opportunity to expand and improve a system that’s already working. “In a perfect system,” he said, “zabaleen will be formally licensed as the owners of their recycling businesses. In such a system, they could make even more money.” Of course the government will benefit too. Dr. Hussein hopes the eradication of illegal dumping and the transition to environmental landfills will reduce future cleanup costs related to soil and water contamination.

Unlike the Ministry of Planning’s PowerPoint, Dr. Hussein’s plans are rational and plausible—especially because most of the cooperation he describes is already happening. The cooperation between multinationals and zabaleen just needs to be formalized to achieve maximum efficiency and to promise that the zabaleen get a fair cut.

While I was in Cairo, the Spirit of Youth Association was working with a Gates Foundation grant to explore possibilities for the zabaleen to integrate with the formal waste management sector. The organization surveyed eight hundred garbage collectors to ask if they wanted to be licensed, and the overwhelming response was “yes.” For all the zabaleen have been able to build out of trash, they’ve never been able to achieve real security. Formalization would legally sanction their operations and protect them from exploitation.

On the downside, formalizing the zabaleen and moving recycling workshops out of the Garbage City might erode the sturdy village culture that has allowed the community to thrive. In the Garbage City, the family is the best guarantee of security one can hope for; people still pay into collective pots to help friends get married or to handle medical emergencies, marriages are still arranged the old fashioned way, and children take care of their parents as they grow old. An incredibly complex web of business relationships exists in the Garbage City, but family relationships are the anchors of existence. The zabaleen have always been more like farmers who barter and trade at the village market than factory workers and owners whose relationships and decisions are based entirely on financial transactions. But large export businesses like Rizeq Youssef’s are all the evidence one needs to conclude that things are changing fast. The village is getting bigger, and so are the ambitions of its entrepreneurial youth.

If any of the Garbage City elders fear a new era in which the younger zabaleen base their decisions on money instead of family, Riz will allay their concerns. While he invests in growing his business, he also invests in his family; Riz pays tuition for all of his younger siblings, takes care of his grandmother, and even set his father up with a small shop in the neighborhood. He pays his workers more than they would earn with a multinational—more, in fact, than Riz made as a government teacher. Riz has never forgotten where he came from.

At about midnight one evening toward the end of my trip, I ride up to the Garbage City to meet a garbage collector who agreed to take me on his route. The taxi driver laughs when I ask him to take me to Manshiet Nasser.

“You’re kidding, aren’t you?” he asks.

When I get to the coffee shop where I arranged to meet the collector, he’s nowhere to be found. He probably got worried that I would attract too much attention from the police—the most common reason every collector but him refused to take me along. As luck would have it, I find Riz at an Internet café across the street. He joins me for a cup of anise-flavored yansoon.

I tell him that Moussa and Samaan have been fighting constantly, and that Moussa threatened to give up recycling altogether and try to find work as a tour guide. I tell him how Moussa said, “I am tired of carrying my whole family.”

“It’s not true,” Riz says. “It’s just that he has changed and now he looks at them as simple. He just doesn’t see how much they do for him.” Riz takes a sip of his yansoon and leans in across the table.

“Believe me,” he says, “nobody does anything alone in this place.”

In February, after the revolution in Tahrir Square, Elliott Woods returned to Manshiet Nasser’s garbage village. To read how the people in this article are confronting Egypt’s new future, go to vqronline.org.