with Masao Miyoshi

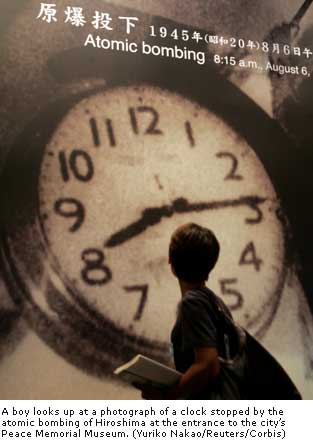

On August 6, 1945, just before 8:15 AM, Japan time, fourteen-year-old Akihiro Takahashi and his classmates at Hiroshima Municipal Junior High School were lining up in the schoolyard for morning assembly. High up in the sky, he saw a B-29 approaching. Instinctively, he pointed and soon all of his classmates were pointing as the plane was about to pass over. The teachers came from the school and ordered the students to quiet down and fall in for assembly. Takahashi looked at the platform where his teachers stood, then everything went black. When the darkness faded and his vision returned, Takahashi saw his fellow students lying around him, all of them badly burned and cut. When he stood, he couldn’t believe his eyes. “Everything had collapsed for as far as I could see,” he told a documentary film crew twenty years ago. “I thought the city of Hiroshima had suddenly disappeared.”

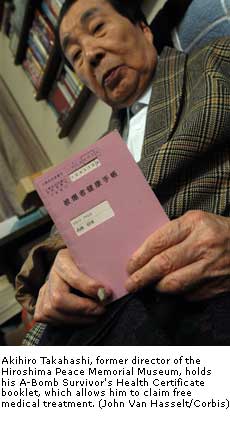

In 1979, thirty-four years after the atomic blast at Hiroshima, Takahashi became director of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and one of Japan’s most conspicuous hibakusha—literally, “those who were bombed.”  Talking this summer in a basement office at the museum, he divided his life story into three fourteens: the fourteen years before the bomb fell, the fourteen hundred meters he stood from the bomb’s hypocenter (distance from the hypocenter is a crucial factor in certification as a hibakusha), and the fourteen hospitalizations he has endured because of radiation-related illnesses. He has delicate features and a very precise way of speaking as he remembers how on that day (as everyone in Hiroshima refers to the date of the bombing), he was burned all over his body. His charred skin sloughed off and hung in long swathes exposing the muscles underneath. Like so many of the survivors, he made his way to the river to try to extinguish his burning flesh. He had no way of knowing then that the physical suffering had only begun. He spent the first year and a half after the blast in the hospital. The most serious damage was to his right arm, where the muscles and bones in his elbow and first four fingers had fused. From the radiation burn, he developed large red keloids on his wrist, which surgeons finally removed in 1954. As a photograph-illustrated placard in the museum explains, a piece of radioactive glass that lodged in his finger affected the cells in the nail bed of his index finger. To this day, the gnarled nail grows black and repeatedly falls out. He frequently visits an ear doctor, an eye doctor, a dermatologist, and a surgeon. He joked that the only kinds of doctors who have never seen him are gynecologists and psychiatrists. But behind the light façade is the fact that he now must visit a hospital daily for hour-long treatments for liver cancer and the admission that he worries every day about his health.

Talking this summer in a basement office at the museum, he divided his life story into three fourteens: the fourteen years before the bomb fell, the fourteen hundred meters he stood from the bomb’s hypocenter (distance from the hypocenter is a crucial factor in certification as a hibakusha), and the fourteen hospitalizations he has endured because of radiation-related illnesses. He has delicate features and a very precise way of speaking as he remembers how on that day (as everyone in Hiroshima refers to the date of the bombing), he was burned all over his body. His charred skin sloughed off and hung in long swathes exposing the muscles underneath. Like so many of the survivors, he made his way to the river to try to extinguish his burning flesh. He had no way of knowing then that the physical suffering had only begun. He spent the first year and a half after the blast in the hospital. The most serious damage was to his right arm, where the muscles and bones in his elbow and first four fingers had fused. From the radiation burn, he developed large red keloids on his wrist, which surgeons finally removed in 1954. As a photograph-illustrated placard in the museum explains, a piece of radioactive glass that lodged in his finger affected the cells in the nail bed of his index finger. To this day, the gnarled nail grows black and repeatedly falls out. He frequently visits an ear doctor, an eye doctor, a dermatologist, and a surgeon. He joked that the only kinds of doctors who have never seen him are gynecologists and psychiatrists. But behind the light façade is the fact that he now must visit a hospital daily for hour-long treatments for liver cancer and the admission that he worries every day about his health.

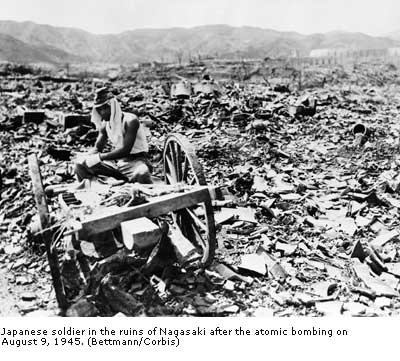

By now such stories are dangerously familiar. Though they have not really been assimilated, they have been dismissed as part of our past. As though we were not still suffering the consequences of the horrifying precedents set sixty years ago. As though that past were not creating the present—and the future. The press revisits the statistics every August, adding extra column inches and sound bytes every decennial. But the sheer size of the devastation makes it almost impossible to comprehend, much less describe: in Hiroshima, at least 66,000 people were incinerated in an instant, at least 30,000 three days later when we used a second bomb, codenamed “Fat Man,” on Nagasaki. Exact casualty figures are impossible to state, because population records turned to ash along with the record-keepers, and radiation caused many deaths long after the actual explosions. Hiroshima’s current mayor, Tadatoshi Akiba, a former math professor at Tufts, published an article in 1983 in which he calculated that 200,000 people had died as a result of the bomb in Hiroshima by 1950, and another 140,000 in Nagasaki. Nearly all were civilians—only 150 Japanese military personnel were killed in Nagasaki, for example—and at least 10,000 are definitely known to have been children.

It is a little-known fact that 3,000 civilian U.S. citizens were in Hiroshima at the time of the bombing—about the same number as were killed on 9/11. Most were women and children, and history has nearly succeeded in erasing them. They are rarely mentioned because nearly all of them were either wholly or partly ethnically Japanese. They were wives and children of Japanese-Americans, who had gone to visit relatives and then been trapped by the war.

But the statistic that Americans might be most surprised to learn is that 226,598 officially certified survivors of the atomic bombings are still alive in Japan today. The actual number of hibakusha is likely much larger, as many could not meet the strict and sometimes arbitrary qualifications for certification, while others have left Japan. The average age of these witnesses, however, is now seventy-three. Most have been struggling with radiation-related illness for much of their lives, and death will surely have silenced the majority of them by the seventieth anniversary of the bombing in 2015. This then, the sixtieth anniversary, is quite literally a last chance. A last chance to remember and record. A last chance to educate.

On the wall of the Peace Museum are messages from heads of state and other celebrities. Most are sanctimonious and trite, but Leonard Bernstein is an exception. His simple statement, written on the fortieth anniversary of the bombing, seems to capture the overwhelming urgency felt today, “Too many words already—not enough action!”

* * * *

The early history of Hiroshima dates back to the 6th century, when some of the first Shinto shrines were erected in Hiroshima Bay. The Itsukushima Shinto Shrine, probably dating to the 13th century, stands as a relic of that early era. Modern Hiroshima, meaning “wide island,” was founded in 1589, on a flat delta where the seven channels of the Ota River empty into the Seto Inland Sea, when Mori Terumoto, a regional warlord, built his “Carp Castle” on the bay. During the Edo period, Tokugawa Ieyasu divided Hiroshima into two domains—the Fukuyama Fief and the Hiroshima Fief. Later, the two regions were rejoined into the Hiroshima Prefecture with Hiroshima City as its capital. The city’s many canals and wharves made importing goods from the countryside easy, while its bridges connected all parts of the growing metropolis. By the time of the first Sino-Japanese war in 1890s, Hiroshima had become such an important base for the Japanese military that the Imperial Headquarters were temporarily relocated there.

In April 1915, construction was completed on the Hiroshima Prefectural Commercial Exhibition Hall on the banks of the Motoyasu River. Jan Letzel, the Czechoslovakian architect who designed the structure, ordered that the building be built from brick and mortar reinforced with a steel frame for the interior and stone for the exterior. It was a daringly modern structure, compared to the rest of Hiroshima, but its purpose was to promote the city’s innovation and economic vitality; it required a grand, twentieth-century design, the centerpiece of which was a five-story stairwell capped by a copper dome. During the war, as Hiroshima’s economic might diminished, the hall was commandeered for low-level governmental offices—which made it a target.

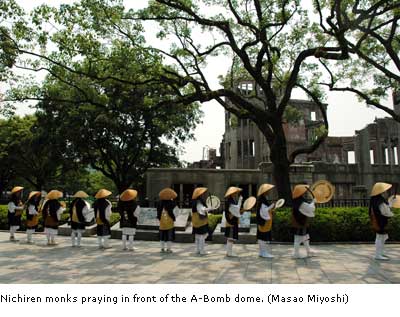

The exact hypocenter of the Hiroshima bombing lies just 160 meters southeast of the former Exhibition Hall. Everyone inside the building was killed instantly, but some mysterious combination of the direction of the blast (coming from above, rather than emanating outward) and the sturdy construction left much of the building itself intact. The warped metallic skeleton of the dome towering above the rubble of Hiroshima became one of the most photographed sights and recognizable emblems of the destruction. It was decided early on to preserve the building, now known locally as the A-Bomb Dome, in this state of ruin to keep the memory of the bomb alive after the rest of the city was rebuilt. Officially renamed the Hiroshima Peace Memorial, the A-Bomb Dome was added to the United Nations’ list of World Cultural Heritage sites in December 1996—over the objections of the U.S. and China.

Masao and I kept passing the dome on our way to and from the museum. Once, we saw a group of Buddhist monks banging prayer drums in front of it; tourists, mostly foreign, were clicking shutters, eager to capture on film the monks’ picturesque conical hats, black robes, and white leggings, their exotic prayer drums and rosaries. I wondered, aloud, if they were praying for peace. Masao said, “I don’t think so; they’re Nichiren monks. That sect was important to a lot of officers in World War II. It has been associated with militarism for a long time.”

* * * *

Takahashi resigned as director of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum in 1983, in part because of health problems, but also because he feared that the museum would never fulfill its mission to memorialize and educate. Both Hiroshima and Nagasaki are well known throughout the world, Takahashi agreed, “but their miseries are not understood. That’s what I feel when I go abroad. The names of the cities are recognized but the extent of the destruction is very little known. Whenever I talk about my experience, people say, ‘Was it really that bad?’” He believes this ignorance can mainly be attributed to the censorship imposed by the U.S. Occupation authorities, who forbade reporting about the devastation, banned photographs of human casualties (permitting only photos of destroyed buildings) until 1952, and on top of such censorship prohibited mention of the censorship.

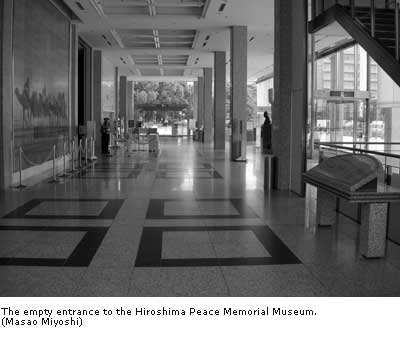

Over the last fifteen years, however, the number of American and other foreign visitors to the museum has been rising. They come from so many different countries that audioguides now are available in seventeen languages. But, while the number of foreigners has increased, overall attendance has fallen off sharply. In 1991, the all-time peak year, there were nearly 1.6 million visitors to the museum, while last year there were barely a million. It may be too soon to speculate about this year’s total, but on one July afternoon, we scanned the lobby and could find no one but a security guard. When we went to the museum’s competitor, the Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall, we were alone in the Hall of Remembrance, too.

Takahashi explains that Hiroshima was once a popular destination for school trips, but in recent years the education ministry had been putting pressure on the teachers’ unions to discontinue peace education and to promote nationalism instead. The Hiroshima prefectural Board of Education is especially strict, he said, because the city of Hiroshima is such a hotbed of political activity. When teachers in the Hiroshima schools protested the imposition of singing the national anthem in school by lip-synching, the government sent representatives to monitor the volume at which the anthem was sung.

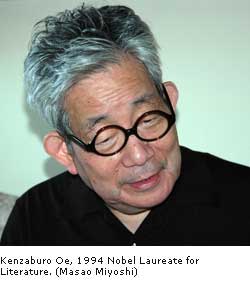

And it’s not just in Hiroshima. The education ministry has been promoting nationalism across Japan by starting to enforce patriotic indoctrination in the schools. In Tokyo, for example, the Metropolitan Board of Education—made up partly of elected representatives and partly of members appointed by the conservative Tokyo governor (and former novelist) Shintaro Ishihara—has the sole power to decide which texts meet national standards. The 1994 Nobel Laureate Kenzaburo Oe, who has been writing about this issue recently, said he believes that the board does not actually read the textbooks but instead works from a handbook which quantifies the patriotism-promoting tendencies of a text according to the numbers of times it mentions certain issues, such as the island of Takeshima, which the Japanese government contends belongs to Japan, but which the Korean government believes is Korean (and calls Dokto); or the number of times the words “Japanese traditions” appear. There is also a volunteer committee, composed entirely of well-known editors and critics—all right-wing extremists—formed specifically to write and promote a nationalistic textbook. Teachers have been resisting the use of such revisionist texts, but we heard in Hiroshima about retaliations—punitive postings to locations where a long commute would be required, for example—against teachers who resisted the directives of their local boards. The curriculum now not only omits mention of Japanese aggression in Asia but gives very little attention to the atomic bombings.

To combat such efforts, Takiko Sadanobu, a very petite seventy-year-old Hiroshima hibakusha with a perfectly square jaw and a gentle smile, has been traveling to schools all over Japan, talking about her experience of the A-Bomb.  Even teachers know little about the bombings, she says. Speaking in Japanese, she told us that the most common response she gets, from teachers and students alike, is, “Why didn’t we know?” She worries the children of hibakusha will not be able to take over as narrators: their parents told them too little, wishing to protect them from both the painful knowledge and the prejudice against hibakusha that would jeopardize their career or marriage prospects. Besides, she says, no one is interested in hearing from the second generation, which can’t compete with the vividness and immediacy of eyewitness narrators.

Even teachers know little about the bombings, she says. Speaking in Japanese, she told us that the most common response she gets, from teachers and students alike, is, “Why didn’t we know?” She worries the children of hibakusha will not be able to take over as narrators: their parents told them too little, wishing to protect them from both the painful knowledge and the prejudice against hibakusha that would jeopardize their career or marriage prospects. Besides, she says, no one is interested in hearing from the second generation, which can’t compete with the vividness and immediacy of eyewitness narrators.

She proudly shows us a thank-you letter from a twelve-year-old schoolgirl. “She was deeply moved,” Sadanobu said, “to hear what it felt like to lift your friends’ bones from the rubble.”

* * * *

One would like to believe that the antiwar feeling of Japan will be perpetually preserved by great works of literature, like Masuji Ibuse’s Black Rain, Shohei Ooka’s Fires on the Plain, Kobo Abe’s brilliant anti-nationalistic parable Woman in the Dunes, and Nip the Buds, Shoot the Kids by Kenzaburo Oe. There are many classic Japanese films, too, that convey a deeply disillusioned view of war, even when they are as violent as Akira Kurosawa’s plague-on-both-your-houses classic Yojimbo or as shamelessly tear-jerking as Isao Takahata’s internationally acclaimed anime Grave of Fireflies.

The last has a particularly hard-to-exorcise immediacy, probably because it was based on an autobiographical work by Akiyuki Nosaka, whose little sister died when he, still a child himself then, was trying to take care of her after they were orphaned in the war. Something similar is true of Keiji Nakazawa’s manga (or comic book) Barefoot Gen: A Story of Hiroshima, which might be easier to dismiss as unusually entertaining Marxist propaganda if its author—seven years old at the time the bomb was dropped on his city—had not lived through so many of the oppressions its boy-hero suffers. The most memorable journalistic accounts of nuclear devastation, like John Hersey’s Hiroshima (a detailed account of how the bomb affected six residents of the city) have focused on its impact on the daily lives of ordinary people. Oe’s nonfictional Hiroshima Notes, too, derives much of its power from its examination of how encounters with bomb survivors transformed its author’s consciousness.

But while historians’ patient documentations are indispensable to intellectual consideration of the cases to be made for and against war in general and atomic weapons in particular, I am not sure rationality is an adequate guide to right and wrong. I found my own pacifistic inclinations taking on a new emotional urgency after I began seeing Masao.  An American now, he was born in Japan and survived the Tokyo firebombings of March 9-10, 1945, which reduced sixteen square miles to rubble and killed at least 84,000 people immediately—a record-breaking number before the dropping of the A-Bombs—and 100,000 or more, ultimately, as others died later of their injuries.

An American now, he was born in Japan and survived the Tokyo firebombings of March 9-10, 1945, which reduced sixteen square miles to rubble and killed at least 84,000 people immediately—a record-breaking number before the dropping of the A-Bombs—and 100,000 or more, ultimately, as others died later of their injuries.

Masao has shared some of his painful memories of that air raid with me: the hardest one to bear was that of the pervasive smell of broiled human flesh—exactly like steak, he said. He worked with his brother and some soldiers to tear down a burning house, preventing the fire from spreading further in his neighborhood, and later walked through streets full of charred corpses. He saw the burned bodies of mothers and fathers hunched over the burned bodies of the children they had been unable to protect, and the flame-blackened remains of men still uselessly shielding seared women. Most were burned too badly to be recognizable as individuals, he said; clothes and hair gone, male and female could be told apart only from what was left of the genitals.

As we traveled across Japan together this summer and heard many first-person accounts of the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, again and again, he responded to hellish specifics by saying, “I saw that, too, in Tokyo,” or “Yes, it was like that for me, too.” Yet he also stressed the differences between the A-Bomb and conventional weapons: A-Bomb victims exposed at or near the hypocenters were vaporized or reduced to ashes and bone fragments, whereas in Tokyo the victims became “so much rotting meat.” But there were many rotting corpses in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, too, and fewer people left to dispose of them; the grim narratives we heard and read in both cities almost always included mention of flocks of crows feasting on eyeballs. The most important difference between the results of the Tokyo air raids and the A-Bombings was, of course, the radiation, which continued killing survivors—and visitors who came to the sites from elsewhere—long after the attacks.

* * * *

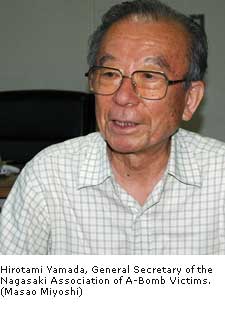

Hirotami Yamada, General Secretary of the Nagasaki Association of A-Bomb Victims, was fourteen years old, an eighth-grader, when the bomb was dropped on Nagasaki.  He is a slight man, but—in a quiet way—forceful. He wears enormous glasses, which enhance an air of authority that was probably cultivated in the classroom; he taught business administration before becoming a full-time activist. Speaking in Japanese, facing a large poster of Martin Luther King and sitting under a huge, discomforting drawing of human figures writhing in flames, he recited yet again the narrative he had been repeating for many audiences time after time, year after year.

He is a slight man, but—in a quiet way—forceful. He wears enormous glasses, which enhance an air of authority that was probably cultivated in the classroom; he taught business administration before becoming a full-time activist. Speaking in Japanese, facing a large poster of Martin Luther King and sitting under a huge, discomforting drawing of human figures writhing in flames, he recited yet again the narrative he had been repeating for many audiences time after time, year after year.

In August 1945, Yamada’s family consisted of his mother and his father, an older sister, and two younger brothers. It would have been summer vacation, only there was no summer vacation by that point in the war as children were kept in school so their parents could work in the war factories. Because the middle school Yamada attended was on the far side of the mountains, he was unharmed by the blast. He showed us his lavender hibakusha ID, with his distance from the hypocenter noted as 3.3 km; his father—only 1.3 km—is recorded there also.

Yamada made his way back with great difficulty through the ravaged city, walking among people with horrifying injuries, seeing corpses everywhere and wondering all the time if his family was still alive. When he finally reached his home, he found that the house had collapsed, pinning his mother, sister, and two brothers under the roof—but they were alive. Finding them unharmed gave Yamada hope that his father might return also.

Three days later, on the twelfth of August, his baby brother died in his mother’s arms as the family was lying on the floor together, trying to sleep in the summer heat. The next day, the thirteenth, Yamada woke to find his sixteen-year-old sister dead also. After two days, something had to be done. The dead bodies were hideous to look at, and smelling worse. He went out, scavenged some lumber, and made a bonfire for the corpses of his two siblings. He stood with his mother, watching them burn. “Looking at her children burning must have been so hard for her,” he said, “but I was a fourteen-year-old kid and couldn’t imagine what she might be feeling. When I look back now, I wonder how I could have let her stay near that bonfire.”

Fearing this strange, invisible affliction, Yamada went with his mother and the only brother he had left, the sixth grader, to his paternal grandmother’s home in Sakaya, twenty-five kilometers away. Entirely by chance, his father had been taken there to the hospital where he was born, because there was no longer a hospital in Nagasaki. When her mother-in-law told her where he was, Yamada’s mother went to the hospital immediately, only to be told her husband was so gravely injured that there was no way he could survive. He was burned all over his face and chest, his back torn apart. She decided to stay there to care for him, but within three days she could no longer move, had lost her energy entirely, and was soon hospitalized herself, along with her younger son, who had the same symptoms. “My mother, my brother, my father—all of them were obviously going to die soon,” Yamada said. But his mother and his brother were declining much faster than his father, and died before the month was over. Somehow, his father survived—despite horrible burning, scarring, and residual radiation—but sixteen years later, in 1961, he was found to have lung cancer, and died at the age of 64. His death certificate mentions no connection to the bombing.

For the first time, in June of this year, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist George Weller’s dispatches from Nagasaki, written in September 1945 for the Chicago Daily News but censored by General Douglas MacArthur, were published in the Mainichi Daily News. Weller, traveling through the hospitals at the time, reported on “a mysterious ‘disease X’” that was killing people long after the bomb had dropped. American radio reports suggested that perhaps the ground around the Mitsubishi plant was poisoned—implying that these unexplained deaths might be the result of some chemical or biological agent in secret development by the Japanese and only released by the bomb’s awesome force.

Weller declined to accept such an explanation. “The atomic bomb’s peculiar ‘disease,’” he reported, “uncured because it is untreated and untreated because it is not diagnosed, is still snatching away lives here. Men, woman and children with no outward marks of injury are dying daily in hospitals, some after having walked around three or four weeks thinking they have escaped. The doctors here have every modern medicament, but candidly confessed in talking to the writer—the first Allied observer to Nagasaki since the surrender—that the answer to the malady is beyond them. Their patients, though their skin is whole, are all passing away under their eyes.”

As Weller filed his daily dispatches by telegraph, he had no idea that they were being intercepted and censored. No one would know what he had seen, nor hear the opinion of Dr. Yoshisada Nakashima, Kyushu’s top X-ray specialist, who arrived in Nagasaki on September 9 and told Weller that he believed these patients were suffering from radiation illnesses. “All the symptoms are similar,” Nakashima said. “You have a reduction in white corpuscles, constriction in the throat, vomiting, diarrhea and small hemorrhages just below the skin. All of these things happen when an overdose of Roentgen rays is given.”

Weller closed by reporting that twenty-five American scientists were due onsite on September 11: “Japanese hope that they will bring a solution for Disease X.”

* * * *

Toshiyuki Tanaka, a research fellow at the Hiroshima Peace Institute, plans to hold an international “people’s tribunal” this winter in Hiroshima to try the U.S. government as war criminals for the atomic bombings. At first, Tanaka’s genial, even hearty, manner and his office decorated with plastic Godzilla figurines would seem at odds with his politically charged activities and his recent research on the history of indiscriminate bombing, but he explained that Godzilla is part of his monster-as-the-bomb thesis. “Compare the first Japanese Godzilla with the one in the American remake,” he said in heavily Australian-accented English. “The Japanese one is a B-29, appearing at night and attacking everyone and everything, people and buildings indiscriminately. And the Japanese Godzilla appeared as a result of the hydrogen-bomb testing in Bikini atoll. In the American film, he’s a precision bomb, attacking only the people who try to kill him. Americans never experienced indiscriminate bombing—until 9/11.” This whole vein of study, he explained, was part of a necessary effort to get young people interested in memorializing the war. “We have to find ways to make peace fun,” he said.

As we talked about the upcoming tribunal, however, Tanaka grew somber, and whenever he said something condemning the United States, he flashed an apologetic look, then lowered his eyes briefly before returning to his plans: hibakusha will testify, including Japanese and Koreans now living in the U.S., Canada, and Australia, along with historians and medical scientists, such as one from Hiroshima University who has specialized in radiation-related illnesses. A group called Lawyers Against Nuclear War will act as prosecutors. Judges will be specialists in international law—including, Professor Tanaka is hoping, one or more retired judges from the International Criminal Court. The verdict will be announced in Washington, D.C., next January. It will, of course, have no legal force, but Tanaka hopes to spark conversation and circumspection about the horrors of war. Asked how he answers people who say that in total war there is no difference between civilians and soldiers, he said, “In my eyes, indiscriminate bombing is discrimination, really, because it targets civilians specifically.” He sees the sixtieth anniversary of the bombings as a great opportunity for educating people about this. “We’re not just talking about Hiroshima sixty years back but about Afghanistan, Iraq.”

He spoke approvingly about a current project of the organization called Peaceful Tomorrow, formed by the families of victims of 9/11. They will be coming to Hiroshima on August 8 with a stone memorializing victims of the A-bomb. The stone will bear some of their names, along with messages of apology from Americans who want to make a public statement of regret about the bombings. They left Nagasaki on August 2 and will wheel this stone in a cart until they reach Hiroshima on the anniversary. Hibakusha organizations, he pointed out, were among the first to contact these families with messages of condolence.

Indeed, the Japanese people have believed for decades that their nation has a special role as peace ambassadors and an obligation to refuse war—an obligation mandated by the American-authored “peace constitution.” But, while Japanese military are still known as Self-Defense Forces, their budget is now the fourth largest in the world—around $46 billion annually, trailing only the U.S., Russia, and China. Since three years after the bombs were dropped “No more Hiroshimas, no more Nagasakis” has been the mantra of pacifists and anti-nuclear activists, but the Japanese commitment to peace has been wavering recently, while the nuclear threat from North Korea and other neighbors increases daily. To make matters worse, the Japanese government, loath to acknowledge Japanese aggression in Asia as a prelude to war, has tended to talk about Japan’s victimization as though the nuclear destruction of two cities had no cause. Even in the Hiroshima Peace Museum, where the massacre of civilians by the Japanese Army—in what has come to be known as the Rape of Nanjing—includes Chinese estimates of 300,000 casualties, the Japanese text on the placard describing the beginning of the war with China in 1931 ascribes responsibility to neither side. It translates as “railroad destruction led to the Manchurian Incident”; the English-language text beneath admits that the Japanese Army blew up the Manchurian railway line.

* * * *

In the last year, Kenzaburo Oe, Japan’s most revered living writer, has founded a nine-member group for the purpose of ensuring the preservation of Article 9, the “peace clause” of Japan’s constitution.  In Tokyo, Oe was gracious enough to invite us to his house for a home-cooked meal that he and his wife, Yukari, prepared. He made the oxtail stew that figures in several of his books, and Yukari made a flaky-crusted pie containing fish and vegetables. Over dinner, Oe talked about the enormous obstacles his group faces. For example, at the Yasukuni shrine, Class A war criminals are enshrined along with the war dead. Any Japanese prime minister who visits it in his official capacity incurs the wrath of peoples Japan victimized during the war: Chinese and Koreans in particular. “So this August 15th—the anniversary of Japan’s surrender—will be an interesting time,” he said. “Koizumi may dissolve parliament at the end of this month. Then he will no longer be prime minister and therefore free to go to Yasukuni, or he will go as prime minister and will be attacked for it and his popularity will go up because people will sympathize with him when he is attacked. He did promise when he ran for prime minister that he would go, so he has to. But Japan will be in a tough position if he does.”

In Tokyo, Oe was gracious enough to invite us to his house for a home-cooked meal that he and his wife, Yukari, prepared. He made the oxtail stew that figures in several of his books, and Yukari made a flaky-crusted pie containing fish and vegetables. Over dinner, Oe talked about the enormous obstacles his group faces. For example, at the Yasukuni shrine, Class A war criminals are enshrined along with the war dead. Any Japanese prime minister who visits it in his official capacity incurs the wrath of peoples Japan victimized during the war: Chinese and Koreans in particular. “So this August 15th—the anniversary of Japan’s surrender—will be an interesting time,” he said. “Koizumi may dissolve parliament at the end of this month. Then he will no longer be prime minister and therefore free to go to Yasukuni, or he will go as prime minister and will be attacked for it and his popularity will go up because people will sympathize with him when he is attacked. He did promise when he ran for prime minister that he would go, so he has to. But Japan will be in a tough position if he does.”

Oe told us about something he had read recently by the critic Tetsuya Takashi, an expert on poststructuralism and Derrida, deconstructing the symbolism of the shrine. It was not clear where the critic’s argument left off and Oe’s own thought began. “Shinto architecture is extremely simplified,” he said. “Compared to Buddhist, the style of beauty is so severe and austere, made all of wood. That simplicity is equated with nature. The Yasukuni shrine has two aspects. The shrine itself is not ideological, but there is a museum on its grounds that provides patriotic propaganda. And in daylight, visitors see nothing but the serenity of the shrine’s simple structure. People living in its precincts want to enjoy nightlife there, though, so there are lanterns after dark, and there are names of prime ministers and other politicians on the lanterns. In the museum, they play the march that was played during the war to celebrate naval victories, and naval flags—the ones with the sunrays—are displayed there. The view that’s put forth in the museum is that Japan made war in an attempt to fight Western imperialism, so although this is not said in the shrine itself, an explicit ideological statement is made through the museum, the lanterns, the marches. Now there is a problem, because the Tokyo junior chamber of commerce has been supporting a program for bringing kids to Yasukuni instead of taking them to one of the A-Bomb museums, and one of the wards in Tokyo already endorsed this program, and the Board of Education has supported taking children to the shrine.” This is the kind of thing that Oe’s group has been fighting, but they are up against powerful pressures—and not just about ceremonial matters.

The Keidanren, a federation of business leaders led by the president of Toyota, is bent on changing a law that prohibits Japan’s exporting arms or weapons-related technologies. Oe explained that such exports are not explicitly forbidden in the constitution but in a statute that was passed thirty or forty years ago, when Takeo Miki was prime minister—Miki’s widow is a member of Oe’s pro-Article 9 group—under pressure from the United Nations. The law forbids such exports to countries already at war. “When Japan was enjoying prosperity, successful businessmen didn’t pay attention to political problems. They just counted money, and it came in anyway. But after the bubble burst, there was deflation and stagnation, and now—particularly in the last two years or so—there has no longer been enough money to go around and they have had to pay attention. They started buying political power through donations and bribes and so on. The military budget has been reduced for the past several years, while the U.S. forces Japan to buy its products. The Keidanren say that the Japanese defense industry is languishing and has to be expanded, and that requires more money than they have, so they want to raise it by producing weapons for the U.S.”

* * * *

In Nagasaki one can ascend to the top of Glover’s Garden on steep moving walkways, scan the harbor from the spot where Madame Butterfly watched in vain for the ship of faithless Lieutenant Pinkerton, and descend again to have one’s photo taken with the statue of Puccini, but wherever you go you find Hello Kitty. Until modern times, Nagasaki was Japan’s most cosmopolitan city. Foreign traders—first the Portuguese, then, after the shoguns began to fear the colonialist ambitions of Catholic powers, the Dutch—were confined there, on an artificial island called Dejima, as the shoguns started fearing Protestant colonialism. They closed Japan off to the Western world for the two and a half centuries of seclusion that ended only when America forced the country open with war ships, in 1853. The result, it seems: the ubiquitous Hello Kitty. She appears on every form of souvenir, always in a hydrangea-blossom headdress—because the city is known for its hydrangeas. One can eat in the highly commercialized Chinatown and shop for tacky souvenirs. Souvenirs, upscale and down, are everywhere—pearl and tortoise-shell trinkets, anthropomorphized sponge-cake dolls (was Sponge Bob a ripoff?), and anything and everything printed with Hello Kitty.

In comparison, Hiroshima has little to offer the tourist apart from Peace—which is to say, its thorough commitment to perpetuation of the memory of the bomb. This has come to be symbolized by cranes made of origami, left in the Peace Park in memory of Sadako Sasaki, who died of radiation-caused leukemia at the age of twelve because of her exposure during the bombing at the age of two. She spent the last year of her life frantically folding cranes in the belief that if she made a thousand of them, she might recover; her classmates joined in the effort; somehow the custom spread among schoolchildren all over Japan. They continued the practice after her death because they were so moved by her story.

What the hydrangea blossom is to Nagasaki, red and golden maple leaves are to Hiroshima. They glow in the early fall, but even here, in the city of origami cranes, Hello Kitty is everywhere. On every street corner and trinket stand, her head appears encircled by sun-touched maple leaves. But Masao and I did not come as tourists. We committed ourselves to study and research. We made repeated trips to the peace museums, looked through grisly photos and heart-rending videos of bomb-survivor interviews, every day.

Always the same: the symptoms of radiation-related afflictions—the vomiting and bleeding, the hair that falls out completely at the touch of a comb. Cancer and microencephalic retardation. Keloids, those strange raised unhealing scars that return after surgical removal. Poring over history books at night. The exhibit of drawings by hibakusha. The same images, over and over, entering through one’s ears, one’s eyes: people and buildings aflame, the human skeletons recognizable among the heaps of ash, the charred and sloughing skin, the water tanks jammed with the corpses of people who had suffocated there when trying to extinguish the flames that were consuming their flesh, the children trapped under collapsing houses.

When did I first begin seeing her, Hibakusha Kitty, with a headdress of flames, her charred skin sloughing off? Was it when Professor Tanaka said he was trying to address the indifference of the younger generation by thinking of ways to make peace fun? Or was it between trips to Japan, when I took in the Little Boy show at the Japan Society in New York? Curated by the artist Takashi Murakami, it covers both the postwar pop culture associated with otaku (a peculiarly Japanese variety of nerd) and some contemporary artists’ response to it. As I learned there, Hello Kitty was the first character created with no context, attached to no narrative, existing for no purpose but to market herself. Cultural-studies types have made much of her mouthlessness. What will become of the A-Bomb narrative when it has no context, when all the characters it is attached to are dead? In one of my visions, Hibakusha Kitty had keloids where a mouth should be; there is more than one way of screaming.

* * * *

Mitsuo Okamoto so neatly fulfills one stereotype of the educator in Japan that he could have been the model for the long-haired, bushy-eyebrowed teacher who can be seen in illustrations of a popular series of cram-school workbooks for children there.  Described by Professor Tanaka as the “father of Peace Studies,” which Okamoto teaches at Hiroshima Shudo, a private university, he was also a candidate, last year, to represent Hiroshima in the Upper House of the Diet (the Japanese parliament), but lost to the conservative incumbent. Running with the slogan, “Peace and Love,” he came in third. He is a Christian (belonging to the unidenominational Protestant Church of Japan) who perfected his completely fluent English in a seminary outside Philadelphia and has taught in several foreign countries, including the U.S. and Britain; he fairly radiates a commitment to faith, hope, charity, and turning the other cheek. He is one of the three directors of the Hiroshima Alliance for Nuclear Weapons Abolition (HANWA)—founded, as he explained, in an effort to reconcile the various warring factions of the peace movement.

Described by Professor Tanaka as the “father of Peace Studies,” which Okamoto teaches at Hiroshima Shudo, a private university, he was also a candidate, last year, to represent Hiroshima in the Upper House of the Diet (the Japanese parliament), but lost to the conservative incumbent. Running with the slogan, “Peace and Love,” he came in third. He is a Christian (belonging to the unidenominational Protestant Church of Japan) who perfected his completely fluent English in a seminary outside Philadelphia and has taught in several foreign countries, including the U.S. and Britain; he fairly radiates a commitment to faith, hope, charity, and turning the other cheek. He is one of the three directors of the Hiroshima Alliance for Nuclear Weapons Abolition (HANWA)—founded, as he explained, in an effort to reconcile the various warring factions of the peace movement.

We heard a lot about this from the peace activists we interviewed. Nagasaki resents the way Hiroshima has hogged history’s spotlight—one former Nagasaki mayor, Hitoshi Motoshima, even wrote an article called “Hiroshima, Don’t Be Arrogant.” In Hiroshima, the national government’s Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims competes for visitors with the city-run Peace Memorial Park. Japan’s two major anti-nuclear organizations, the Socialist Gensuikin and the Communist Gensuikyo (whose names have such a nearly identical meaning that translating them is pointless) have been fighting with each other as long as they have been in existence, and although their original battles centered around now obsolete East-West affiliations, their representatives are still for the most part unwilling to sit down in the same room together.

Through his groups, Okamoto tries to pressure the Japanese government into pressuring the American government to stop nuclear proliferation. They also try to raise American consciousness directly—HANWA, for example, buys a large ad in the New York Times every year. Even he concedes that such efforts are small and may not have much effect. “I’m not so optimistic as to believe we can change people’s attitude overnight,” he said, “but the peace movement is an accumulation of small efforts, and without the hope of change we could not continue to be engaged. It’s not easy to assess any social movement: you can judge success or failure only after ten or maybe a hundred years. If we had not done as much as we have, perhaps the present situation would be worse. And after all, we have been successful in that nuclear weapons have never been used since Nagasaki.”

It’s hard to see the avoidance of nuclear annihilation as a human victory—especially when one considers the numbers. In 1945, there were only six nuclear weapons in the world; the United States had them all. During the Cold War, the U.S. had over twenty thousand and in 1970, the U.S.S.R. had between eleven and twelve thousand. Current figures vary somewhat according to sources, like the Hiroshima and Nagasaki casualty statistics, but here again, the general tendency is clear: according to the 2005 World Almanac, the U.S. has over ten thousand now, and Russia has between eight and nine thousand. This may look like progress in a peaceful direction, but U.S. spending on nuclear development is a gasp-inducing $40 billion dollars a year. (Compare this with the $124 billion in annual aid that Jeffrey Sachs’ recent The End of Poverty estimated could wipe out world hunger.) There are now nine countries with nuclear arsenals and over forty more nations capable of producing them. The conference in May of this year for reviewing the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty was a debacle; the Bush administration is poised to build a new generation of small nuclear weapons, especially “earth penetrators,” plainly hoping to create a climate in which their use will be acceptable.

* * * *

I have always regarded any state-sanctioned violence deliberately directed against civilians as unacceptable, even when told that, paradoxically, lives were saved by bombing Hiroshima (to say nothing of Nagasaki, where the bombing seemed an incomprehensibly gratuitous cruelty even to General “Tooey” Spaatz, commander of the unit that dropped both atomic weapons). The victims there were mostly starving and powerless civilians—the old, the sick, the wounded; women (who, it should be stressed, could not even vote then in Japan) and children. Despite the overwhelming contrary consensus of historians with access to formerly classified or otherwise censored documents, our government insists the nuclear atrocities in Hiroshima and Nagasaki were somehow essential to save large numbers of lives; the figure usually given is “a million.”

This belief, this rationalization, is shared by many Americans even though evidence to the contrary is now abundant and easily available: the most detailed refutation can be found in Gar Alperovitz’s exhaustive, copiously documented The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb and the Architecture of an American Myth (1995). Alperovitz cites a worst-case U.S. military estimate of the time, according to which no more than 46,000 lives at the most would have been lost in an invasion—which was a far-fetched possibility anyway—and convincingly refutes the “million lives saved” theory. Dwight D. Eisenhower, himself—then Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Forces, soon to be chief of staff of the U.S. Army, and subsequently U.S. President—had strongly urged that “this horrible and destructive” weapon not be used, and he was not alone among the informed and the powerful in objecting.

Maybe, like me, you weren’t even born when the atomic bombs were dropped, but we’re Americans, so—even though I disapprove of using nukes or even keeping them around—the passive voice, “were dropped,” feels like a cop-out. It should not be said that bombs were dropped. We must admit that we dropped bombs. We may not approve of many things the U.S. government did then, or is doing now, but since it is our government we have to acknowledge some kind of complicity.

The opportunity to confront these difficult contradictions was lost ten years ago, when a planned Smithsonian Institution exhibit about the end of World War II was reduced to a display of the forward fuselage of the Enola Gay under pressure from veterans’ lobbies. There are people in Japan, too, who would prefer to see their country as blameless. On July 26 of this year, the Memorial Monument for Hiroshima, City of Peace—designed, like both of Hiroshima’s peace museums, by Kenzo Tange—was vandalized. The cenotaph contains the ashes of A-Bomb victims, and an eighty-volume list of names—currently 237,062, and growing every year. The memorial famously bears the inscription, “Rest in peace, for we will not repeat the mistake.” The vandal attempted to chisel off the second clause. The next day, Takeo Shimazu, a man in his twenties, turned himself in, asking authorities, “Why should the Japanese apologize on a monument we built? It is the Americans who committed the mistake.”

Time and again, Masao and I heard this feeling echoed—especially as parallels were drawn between American policy then and American policy now. Last year, in an official “peace declaration” read out loud to an international audience in the Peace Park that now stands where the bomb fell, Hiroshima Mayor Akiba stated that “the egocentric worldview of the U.S. government is reaching extremes.” He specifically condemned American disregard for the U.N. and international law, and our failure to cooperate in nuclear nonproliferation. In the visitors’ notebook of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum where many visitors, of many nationalities are invited to write their impressions, many put their opinions more bluntly. One Japanese had observed, “America is the worst country”; another Japanese visitor had added, “It’s still going on, in Iraq.” Akihiro Takahashi agreed, saying simply, “It is easy to hate the U.S. now.” Allowing such anti-American feeling to grow in Japan, and around the world, can only doom our future, and our claim that the development of the atomic bomb was intended to put an end to war grows harder to defend every time we display our willingness to bomb civilian targets.

Many years ago, when I lived in the town of Kamakura—a tourist draw for its many temples and its enormous Buddha statue—there was an emaciated old woman with brittle-looking grizzled hair and hauntingly accusing eyes who spent her days at the railroad station, ranting unintelligibly and throwing stones at all the Western sightseers who got off the trains. The people there told me she had lost her mind after every one of her relatives was killed in the war. The local authorities made sporadic efforts to stop her, but treatment for mental illnesses was fairly minimal in Japan at that time, and her aim was so poor and her pitching arm so weak that she presented no threat. She would disappear sometimes, but always came back after some weeks or months to resume her dismal vigil. I have thought of her often. I have no way of knowing whether war created her madness or only provided its futile and arbitrary focus, but she has become my emblem for the self-replicating tendency of violence in all its senselessness, when suspended, as she perpetually was, between the will to do harm and the means to inflict it.

Such long-festering wounds are polarizing Japan. The less we, as a nation, are willing to work to heal those wounds, the further it seems to push Japan toward nationalism. And, the more we insist on the justifiability of all-out warfare, the more it fuels their perceived need to rearm. Ironically, if the Japanese forsake Article 9 now, those who believe the bombings were necessary to achieve peace in that country will have to face the fact that all those helpless civilians were killed for nothing. And the American soldiers who lost their lives fighting in the Pacific—what will they have died for?