It was a relief to feel the blood rush back into my catatonic limbs when I finally got out of the boat at Tamanthi, a port town on the Chindwin River in northeast Myanmar.

For three whole days, I’d been gazing at the marshy banks of the slow-rolling Chindwin from a banana-hulled boat that was barely wider than my shoulders. The terrain unfolded like a scrolling diorama: white egrets feeding alongside cranes with long, hooked bills and black-rimmed wings; families floating downriver on bamboo rafts lashed together with rope, transporting loads of timber; large, brightly painted river boats, low-slung and bulging with passengers; naked children leaping off the muddy embankments, their mothers scrubbing soapy laundry in the coffee-colored water; fishermen setting nets with empty plastic soda bottles for buoys. I couldn’t talk to any of the people on shore because my guide, Nyunt Khin, spoke about fifty words of English. After a while, the beauty of the shore life couldn’t make up for the repetitiveness. I started feeling like a prisoner on the “It’s a Small World After All” ride.

In Tamanthi, we unloaded our gear and ate lunch in an open-air café that smelled like feet. Nyunt Khin arranged motorbikes for the trip to Layshee, a large town high in the Naga Hills near Myanmar’s northwestern border with India. There, we planned to stay for several days with the descendants of headhunters. The Naga tribes span both sides of the border, and no one is exactly sure what binds the disparate groups together as an ethnic group. Philologists can’t agree on whether the ancient Sanskrit word “naga” means “hillmen” or “naked people,” but it never mattered much since both meanings were entirely accurate until about seventy years ago. Until then, the Naga Hills had remained impervious to Hinduism and Buddhism alike, in no small part because wandering strangers—itinerant monks, for example—were juicy targets for headhunters. You see, much more than the fact that they lived in the hills and disdained clothing, it was a common passion for unburdening outsiders of their heads that bound the old Nagas together.

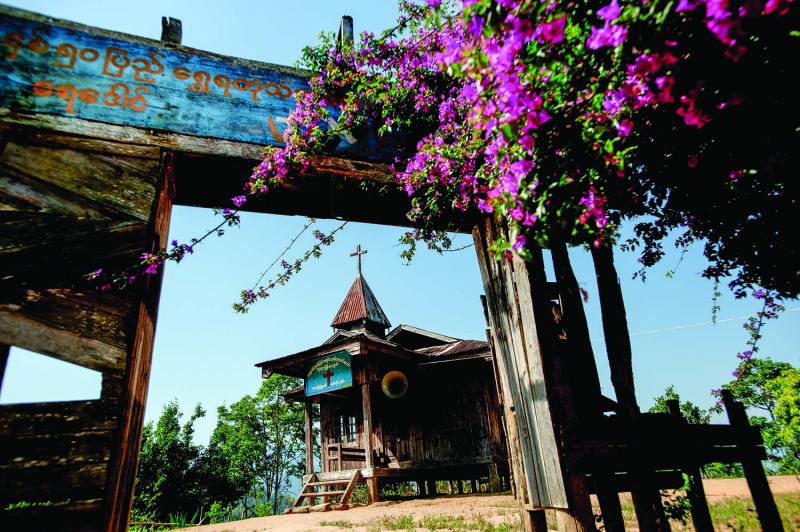

Things changed quickly for the Nagas in the first half of the 20th century. On the Indian side of the border, the British colonials outlawed headhunting and sent battalions of Gurkhas with chamber-loading rifles and scary knives of their own to punish infractions. On the Indian and Burmese sides of the border (everyone still called the country Burma back then), Christian missionaries began making inroads. Headhunting didn’t exactly jibe with Christ’s emphasis on meekness, and with Baptists and Methodists and Presbyterians roaming over the Naga Hills, it suddenly wasn’t cool to be naked anymore.

Japanese soldiers poured into the region in 1939 and stayed for six years, keeping the British colonial army tied down on the Indian border and out of the Pacific Theater. The Japanese and the British built rudimentary roads, which connected the mountains to the Assam Plains in India and the busy Chindwin watershed in Burma. Commerce between the hill Nagas and the flatlanders began to develop. After Burma won its independence from the British in 1947, those same roads allowed the Burmese government to extend its authority into Naga territory.

Suddenly the Nagas were no longer their own people, isolated and left to live as they pleased. All of those changes made it hard to be a true Naga—which really isn’t possible if you can’t cut heads.

In 2012, massive transformation is again imminent for the Nagas and the Burmese beyond. Pro-democracy heroine Aung San Suu Kyi is ascendant after twenty-five-plus years of off-and-mostly-on house arrest. Crippling international economic sanctions, set in place after the nullified democratic elections of 1990, have largely been lifted. The government is easing restrictions on tourist visas and courting foreign investors, who are drooling over the country’s abundant mineral and timber reserves. The fog of military rule hanging over Myanmar is finally burning off. In the Naga Hills—one of the most isolated parts of a famously isolated country—I wanted to see what, if anything, remained of the old headhunters’ culture, since I thought the remnants might be wiped out by the coming cyclone of globalization. I was also interested to know what people in one of Myanmar’s peripheral backwaters thought of all the promises from the national capital, Naypyidaw. Even if the generals ceded power and opened up the country, what would that mean for them?

The sun was a blowtorch. It was the hottest part of the afternoon in the peak of the dry season. Nothing stirred, giving the thatched villages a look of abandonment. Nyunt Khin held on as his motorcycle driver whipped around hairpin corners on an asphalt path cutting through sun-scorched bush. I drove solo, my ruck-sack strapped to the back of an 125cc Honda and a lumpy rice bag filled with food and bottled water between my legs. The rice bag made it difficult to keep my left foot on the shifter. The tiny bike’s suspension bottomed out on the smallest bumps. It was fine for the first hour, when we were buzzing down a surprisingly well-paved track. Things got complicated once we began to climb. The asphalt gave way to a patchwork of interconnected potholes, then to deeply rutted clay. Steep first-gear pitches crested and dropped into bone-rattling descents that made the engine and the brakes so hot that we had to stop to throw buckets of water over them.

The air cooled as we gained altitude and the jungle loomed from all sides, thick, dark, and impenetrable. I could hear a cacophony of birdsong over the motorbike’s high-pitched whine. On a high point, I saw a huge cloud of black smoke roiling up from the jungle below. A few minutes later we were upon the fire. Flames licked at a football field of green bamboo, which sizzled and popped like a distant firefight. This was choom cultivation (otherwise known as slash-and-burn), but it looked like a raging wildfire.

Once the flames died down, farmers would come through with their long knives and hack down the charred stumps; then they would plow the newly cleared field and sow it with rice, corn, or soy. After a few years, when the soil’s nutrients had been depleted, the field would be abandoned and the jungle would creep back in. The technique was as old as the country. And it’s a pretty old country.

We shot through the inferno and moved higher. Construction crews had spread tarred, softball-sized rocks on the trail’s steepest pitches in anticipation of the monsoon rains. A steamroller had been making its way along the trail, crushing the large rocks into gravel, but most of the rock beds were still uncrushed. Climbing up the rock beds on skinny tires at a forty-five degree grade was like riding a jackhammer up a staircase. Rounding a corner, I saw an uphill rock bed and immediately noticed a dirt path off to its right. Thinking I was picking a good line, I rode full-throttle into a strip of soft, six-inch-thick dirt. The bike sank and slid out from under me, catching my left leg on the way down and crushing my ankle into the knife edge of a tarred rock.

I rolled up my pant leg to find my ankle swollen to the diameter of a fat eggplant. I patted myself down and made sure I didn’t have any bones protruding from my back or my arms, no organs flopping out of unseen gashes. Amazingly, I was okay, except for what I knew would be bad bruises on my left elbow and left ankle. One of the motorcycle porters gathered some leaves from the jungle and squashed them in his palm, then rubbed the juice on the places where the rocks cut through my skin. “Native medicine,” he said, blood-red betel slime dripping from his teeth.

Soon the road was hugging a high escarpment. We were high up now, somewhere around four thousand feet. A thunder shower had just come through the valley, and the damp air was refreshing, suffused with the smell of the steaming jungle. Mountains carpeted with dense forest were stacked against the horizon in a diminishing gradient of blue.

On a high promontory to the northwest, tin roofs reflected the few rays of afternoon sun that snuck through the clouds. This was Layshee, our destination. We pulled into town at about 4:30 after more than four hours on the bikes, having covered a total distance of about sixty miles. There was no faster or better way than the route we’d traveled. Actually, there was no other route at all between Layshee and the Chindwin, the artery that connects Naga territory to the world. It was the most cut-off place I’d ever been.

I looked around for people who looked more like the Nagas of my imagination, wearing the hand-woven red cotton shawls I’d seen in photos, or maybe not wearing much of anything at all. But the men and women going about their business on Layshee’s main drag looked indistinguishable from the Burmese I’d seen on my trip up the Chindwin. With their long skirts and dowdy blouses, the women would’ve fit in well on the set of Little House on the Prairie. The men wore T-shirts and Burmese longyis—wide, tubular pieces of cloth wrapped tightly around the waist and tied off with a knot, sort of like how you wrap yourself in a towel after a shower. The younger men sported acid-washed jeans and mirror-finish hair helmets that made them look like Japanese cartoon characters. They wore T-shirts with nonsense English phrases. Some of them wore Angry Birds trucker hats, though I doubted any of them had ever seen the game—or even owned mobile phones, which remain very expensive in that part of the world.

The townspeople stared at me as they ambled by, too polite to stand around and gawk, but unable to keep from giggling. The only time foreigners ever come to Layshee is during the Naga New Year Festival in January, when the government issues group permits to tourist companies. For the festival, all the old-timers from the surrounding villages dig up whatever old bits of ceremonial costume they can find. The youth dance what they know of the old dances and everyone gets wasted on beer and whiskey and stuffs their faces with fire-roasted pork and water buffalo. At festival time, tourist companies bring groups up from Yangon, but the interior Naga areas are restricted during the rest of the year. My trip required wangling a $300 permit out of the government’s Ministry of Hotels and Tourism. Even with a permit, I was only authorized to stay in Layshee for four days. Myanmar may be opening for tourism, but the Naga Hills are not.

Our lodge was a two-story building made of dark wood planks with a metal roof. Outside, Naga industriousness was on full display. Women in pastel-colored straw hats were on their hands and knees in the street, spreading aggregate over a stretch of road that was about to be resurfaced. Several men were working at a table, using planes on long planks of wood to be sold for home construction. Small children were swinging full-size axes, splitting gnarly logs into uniform pieces that could be hewn down into chair and table legs. Across the street, men were nailing boards onto the frame of a new wooden house. Movement and noise were everywhere. If the Naga Hills have been slow to develop, it’s not for want of motivation.

I took a chilly bucket shower in an outdoor stall sectioned off with tarps. My ankle looked pretty ugly, but the pain was manageable. When I came back upstairs, I found David Suirungbo, my Naga guide, waiting for me on the balcony. He was reading from the Gospel of Luke in a Burmese Bible. A diminutive forty-year-old with a bright smile and a potbelly, David was born to Christian parents in Somra, a few ridges closer to the Indian border. He moved to Layshee three years ago to marry a woman who owns a small shop in the village. He married late because he’d spent his twenties and thirties roaming the Naga Hills, peddling goods purchased in India on a village-to-village circuit, making money to support his widowed mother and to pay his ten younger siblings’ school fees. During our time together, he would tell me stories about his close encounters with rogue Burmese soldiers, tigers, and swollen rivers that would be unbelievable if it weren’t for his earnestness.

As dusk settled over the deep valley below Layshee, we took a stroll toward a gilded pagoda on a hill at the edge of town. As we walked, David looked up at me and said, “Does your body feel very heavy?” I told him no, that I felt fine. “It’s just that you’re very large,” he said, “I think you must feel very heavy.” Soon we were climbing a steep trail up to the pagoda, and even on my sore ankle I was twenty paces ahead of David, who had already smoked four or five cigarettes in the hour we’d been together.

It was almost dark when we came to the top of the hill, where we found a group of teenagers hanging out, smoking cigarettes away from the prying eyes of the village. One of them strummed chords on a cheap guitar and shyly crooned the lyrics of Burmese pop songs. Looking west toward India, we could see the same trail we’d arrived on curving through the trees toward villages even more remote than Layshee. I pointed toward the horizon. “That’s where I want to go,” I said.

Back at the guesthouse, David sketched a map in my notebook showing all of the surrounding villages. Their names were alluring enough in themselves: Dinglayway Sanpya, Pingnagung, Namiyupi, Koki, Mayaylung, Pansar. I wanted to know if there were any villages where people still lived according to the old ways, where they still lived in traditional long huts and kept up with the ancient animist traditions. David pointed to the dot on his little map labeled Koki. “I think they may have some antiques there,” he said.

I must’ve looked like a kid who’d just dropped his ice cream cone. “You know, all of the people here are Christian or Buddhist now,” David said. “You won’t find anyone dressed in traditional clothing. Some of the people dress more modern than you.”

In the old days, david would’ve had something bigger to groan about than the fact that we’d be hoofing it long distances on steep mountain paths—the very activity he moved to Layshee to avoid. Before Christianity and Buddhism pacified the Nagas, no one would’ve dreamed of traveling from village to village without an escort of warriors with spears and long steel knives called daos, which they could draw from the scabbards on their backs and bury in someone’s skull in about the amount of time it would take to say “Oh, fu …”

In large holes in their ears, the warriors stuffed orchids, bear claws, parrot feathers, and random bits of found brass and steel. They wore leggings and wide bracelets made from tightly woven bamboo, a kind of decorative armor. Headdresses made from cowrie shells and hornbill beaks supported animal skulls and fearsome arrays of feathers that gave their miniature bodies an aspect of fearsome size. Their bare chests and weathered cheeks were thick with tattoos. They would’ve been utterly terrifying, and would’ve loved nothing more than to stumble upon an unsuspecting woman carrying water up to an enemy village. You can guess what would’ve happened then.

In the villages, boys and girls lived in A-frame huts called morungs with thatched roofs that came down almost to the ground. The morungs were like dormitories for the unmarried youth, who were not allowed to live at home with their parents after a certain age. They decorated the morungs with carved planks representing livestock, nude women, and sex positions. To guard against incest, taboos stipulated which boy morungs could carouse with which girl morungs. But there was no stigma whatsoever about sex in the old Naga villages until the missionaries arrived. In the old days, teenage nights were about rice beer and free love.

At least one of the morungs in each village housed a huge drum made from a hollowed out log. The log drum served as the village sound system when it was time for dancing and also sounded the alarm when the village was under attack. Adult men lived with their wives and young children in their own long huts, which they decorated with stone menhirs, plus carved planks, and last but not least, human skulls. For each of these status-conveying ornaments, the man had to throw a huge party for the village called a Feast of Merit. In a roundabout way, the feasts ensured that the village’s limited food supplies were distributed evenly. The feasts also ensured that everyone tied on a good drunk, since it was mandatory to pound mugs of rice beer during the dances.

On the morning after I arrived in Layshee, David met me at the guesthouse and we tromped off with Nyunt Khin toward Yaydong, a nearby village. It was sowing season, so the children were on vacation and joined their mothers and fathers in the fields. I recognized the woven baskets on their backs with woven palm-frond tumpline forehead straps from the old black and white photos of the Nagas from the 1930s, and I was happy to see that they hadn’t been replaced by cheap plastic sacks from China. David pointed out the various fruit trees in the villagers’ gardens: papaya, lime, orange, mango, wild banana. In one of those garden plots, we stopped to talk to an old woman bent over her hoe, scratching at the dusty soil. Her husband sat on a log outside their hut, hacking up a lung. I shook his hand and introduced myself. He informed me he had tuberculosis.

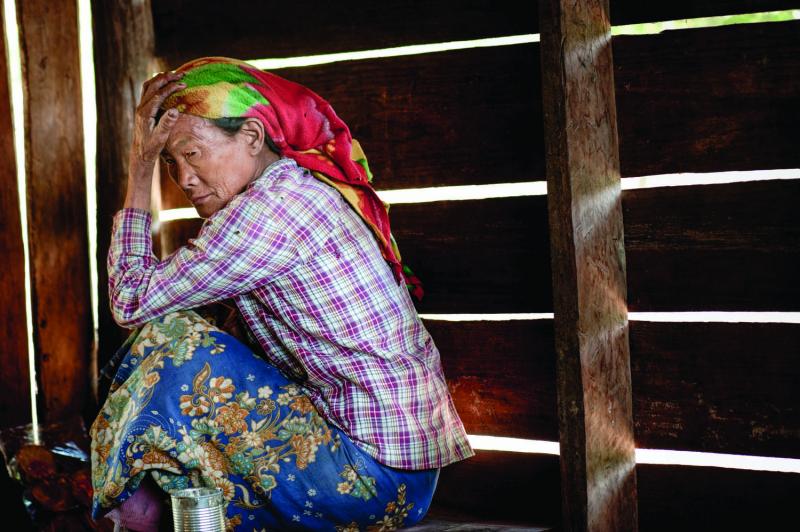

The woman’s name was Bhro Tei. She was a sinewy sixty-five years old, dressed in a threadbare plaid shirt, her head wrapped in a colorful scarf, bead necklaces piled around her neck. For fourteen years she had been shouldering the lion’s share of the work required to keep her husband and herself fed, clothed, and housed. Her husband, Koboh, sixty-nine, couldn’t work because of his illness, and he needed $10 worth of medicine per week. Bhro Tei kept chickens and a garden plot at home, but made most of her money by brewing rice beer and selling or trading it to villagers. She put down her hoe, picked up an axe, and began chopping firewood. She was preparing to leave for several days and nights down in the fields, an hour’s walk from her house, and she was making sure Koboh had enough firewood to cook his meals.

Bhro Tei said she could manage well enough until a few years ago, when old age started to slow her down. She held up her hands for us to see. “See how my fingers are all crooked now? They hurt me,” she said. As far as I could tell, she hadn’t slowed down a bit. I’ve seen people her age in the United States riding scooters in the supermarket. Once she had squared away the house for Koboh, Bhro Tei set off for her fields at a jaunty pace, singing softly to herself. The trail wound downward through the jungle, past terraced rice paddies waiting for the monsoon rains, over narrow log bridges, past a pair of water buffalo grazing in the forest. We arrived at a small clearing with a murky pond and a thatch hut raised off the ground. Bhro Tei took her hoe from her basket and immediately set to work, still singing. I watched her work for a while, then joined Nyunt Khin and David in the hut, where they were sprawled out on bamboo mats around a fire, waiting for water to boil.

Bhro Tei took a break from her work and joined us in the hut, and David asked her what she remembered of the headhunters. “Before I got married,” she said, “we had three skulls. My brothers and one sister were killed by one of those skulls.”

Headhunters believed that you could trap and enslave a human spirit in a captured skull. The enslaved spirits then protected the house and the village as long as they were sated with regular ritual sacrifices. A head that felt jilted by a stingy owner could do awful things—ruin your harvest, burn your house down, kill your children.

“The skull’s jaws chatter before it kills someone,” she said. “This happened in our house.”

The deaths put the fear of God in Bhro Tei’s parents. “The pastor in the village told my parents it was the skulls that killed them,” she said. “After they died, my parents took the skulls to the jungles and destroyed them. They asked the pastor to pray for them and they converted to Christianity.” Bhro Tei and her remaining siblings converted too, and I asked her if she still believed in the skulls’ power after she became a Christian. “No,” she answered, “it must not have been the skulls. It must have been diseases.”

There was still plenty of room in Bhro Tei’s imagination for superstition. Just the other night, she said, the moon was so huge that she was sure it was going to crash down on the earth. She was not speaking figuratively. Then she told us about the were-tiger she recently saw prowling the village. Many Nagas still believe that some humans possess the ability to morph into tigers and travel to the spirit world to communicate with the dead. David noticed my incredulous look. “I’ve never seen one,” he said, “but I have friends who’ve seen them.”

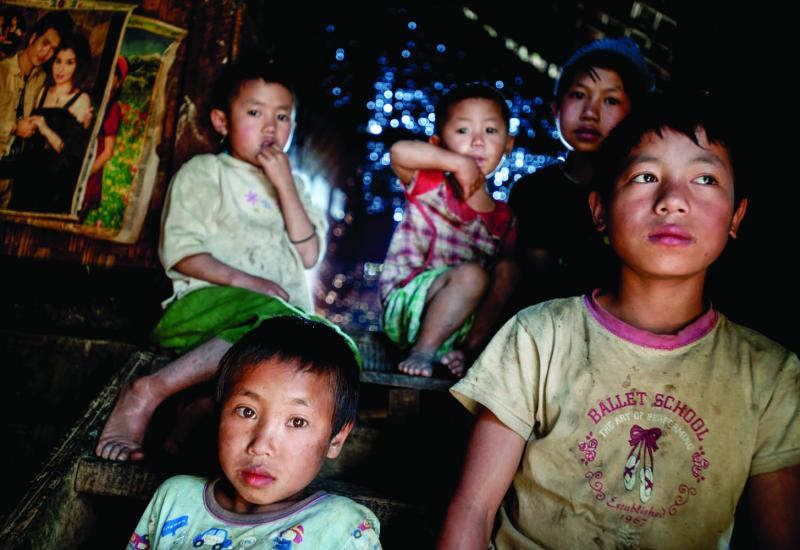

A spare man in a tank top and athletic shorts ducked into the hut and cooked himself a bowl of instant ramen on the fire. Kaman, forty-three, was the owner of the half-acre field, and he allowed Bhro Tei to use a patch of it because he knew about her husband and took pity on her. He hoped the government would make life easier for everyone. His requests were modest: a public rice mill, a mini-hydroelectric turbine, a new school so that kids wouldn’t have to travel to a major city to finish their educations. “The village has changed a lot since the old days. We have tin sheet roofs. Motorcycles allow us to travel faster and farther than before. But still our incomes are very meager. Most of us can’t afford to send our kids for higher education,” he said.

“Military rule has crushed all of our hopes,” he continued. “We’ve had no chance for positive development and we’re not free to live our own lives.” Kaman was pinning his hopes on Aung San Suu Kyi. “She will allow the NGOs and the United Nations to begin full-scale development work,” he said. “I feel with Aung San Suu Kyi something will change.” He took a big slurp of his soup from a ladle lashed to a bamboo handle. “Under military rule I’ve only known oppression and anxiety. I just wish every man would wish for his full human rights and true democracy like I do.”

The next morning, we hiked two hours to a village called Dinglayway Sanpya and drank tea with the chief, Cheri Mu. In raspy whispers, the sedate octogenarian conjured hazy memories of a lost world. “As a child, I lived naked,” he said. “Even the warriors wore only a small sash over their genitals.” A gaggle of Cheri Mu’s grandchildren sat listening near the entryway, clothed in secondhand T-shirts and flip-flops. Cheri Mu was their age when the last of the real headhunters walked the Naga Hills. He could remember a time when the warriors brought a skull back to the village and threw a huge feast, but he was too young to go. “I can’t remember the exact time because I’m illiterate, and I don’t know dates,” he admitted, but he thought it was probably the village’s last raid.

As chief, Cheri Mu kept up with the animist traditions out of a sense of responsibility for the village, even though most of the villagers had converted to Christianity. One day, a wandering Buddhist monk showed up in the village. “He could read palms and tell the future, and he told me that if I didn’t throw away the old customs I would die young, and big trouble would fall upon my family. I believed him, but I decided to convert to Christianity instead of Buddhism because my sons were already Christians.”

After his conversion, Cheri Mu felt a weight lifted from his shoulders. “I felt safe. Before I converted, I was always worried about keeping up with the rituals to make the spirits happy and to protect the village. It was really a burden,” he said. Like many of the Nagas with whom I spoke, Cheri Mu’s conversion seemed more like a switching of alliances than a genuine submission to the one true faith, but it seemed to work for him. Cheri Mu’s son, Kope, nodded in agreement. “I feel much safer since we converted to Christianity because I know that when the heads were in the house they used to do evil things to our family, especially if we didn’t make sacrifices,” he explained. “We couldn’t even go hunting in the jungle without making a sacrifice or the spirits would haunt us. They would shake the trees. I’ve seen it myself.”

We sat around the stone hearth in the central room of Cheri Mu’s house, over which hung a traditional Naga mantelpiece of woven bamboo, on which the family’s pots and pans were stored. My eyes stung from the wood smoke. There are no gas stoves or electric burners in the Naga Hills. Everyone cooks over open fires on the floor, and black tar hangs from the mantelpieces like icicles. The illusion of traveling back in time was romantic to me, the tourist from the electrified world, but it was plainly apparent that the simplest domestic tasks in villages like Dinglayway Sanpya—boiling water for tea, washing dishes—required an extraordinary amount of labor.

Kope, a schoolteacher, had seen enough of the Nagas’ picturesque isolation. “What I regret for the schoolchildren is that they don’t have electricity at home and their parents can’t afford candlesticks for them, so they can’t practice reading at night,” he said. “If we had a public electricity utility, our children could learn much better.” Kope’s wife brought us mashed rice and banana treats wrapped up in banana leaves, a newborn baby snuggled in a sling around her shoulders. “If we could afford it, I’d like to have an electric stove, or to pour a cement floor,” Kope said, “but things like that are so far from what’s possible that I don’t even bother dreaming about it.”

Everywhere we went, David asked if anyone knew of any villages where people still kept skulls. When we were walking through Layshee one afternoon, we met a young motorcycle driver who told us that his village’s chief still had a skull and kept up all of the old rituals to keep the skull happy. The driver’s village, Pansar, lay forty miles farther along the road toward the Indian border. David sent word to the chief with the motorcycle driver that we would be paying him a visit in the coming days.

The ride from Layshee to Pansar took three hours. This time David drove Nyunt Khin, and I rode with a motorcycle driver who happened to be the brother of the girl the Pansar chief’s son had married the week before. His cheeks bulging with betel, he tooled that little bike up and down the rocky paths like a Burmese Evil Knievel.

The chief was waiting for us at his home when we arrived, wearing slacks and a white button-down shirt, his silver hair neatly combed above a drawn face with high cheekbones and a trace of stubble. He would not have looked out of place at a Sunday church service in Iowa, but he was no convert: he was the owner of a skull.

The chief’s name was Yaboh. He was fifty-six, and he guessed the hereditary chiefship of Pansar had been in his family for around 250 years. Compared to his ancestors, Yaboh was a chief in name only. Most of the chief’s traditional duties—adjudicating disputes, performing marriage rites, declaring war—had been assumed by the Burmese government or the local monks and pastors. Almost everyone in the village had converted to Christianity, but some of the villagers still came to Yaboh and asked him to intercede with the skull when they needed help with something. The skull could work wonders for a sick relative, or a jealous neighbor. “Sometimes people come secretly in the night and give their own sacrifices to the skull,” he said. “I know because they tell me later—after they get better.”

The skull could also wreak havoc on people who disrespected it. One time, a villager got drunk and decided to take a piss on the exterior wall of the hut in which the skull hangs. “His balls swelled to the size of a pumpkin,” Yaboh told us. The man pleaded with Yaboh to make a sacrifice on his behalf to appease the skull. Yaboh told him to provide a fresh egg, to tell the skull he was very sorry, and to beg for forgiveness. “He did all of that, and his balls got better immediately,” Yaboh said.

We waited on wooden stools around the hearth in Yaboh’s house while his son ran off to find a sacrificial chicken. The skull would be dangerously unhappy if it were revealed to strangers without a proper sacrifice, Yaboh warned. While we sat there, his wife and new daughter-in-law started preparing lunch over the fire. A hundred or so blackened animal skulls hung in jumbled rows on one wall of the shadowy wood plank room. These were Yaboh’s hunting trophies. Bushmeat still provides a significant source of protein in the Naga diet, and farmers can often be seen carrying archaic muskets along with their wicker baskets and farm tools, hoping to catch a jungle deer or a squirrel unawares. On that day, it might’ve been better if we’d had some bushmeat to sacrifice for the skull, because Yaboh’s son couldn’t find a chicken anywhere. There had been some kind of chicken plague in Pansar several weeks before and most the village chickens had fallen sick and died.

Yaboh decided it would be okay for us to see the skull anyway. He led us out the back door into a dirt plot behind his home where a small shack stood next to a piggery. Yaboh climbed over a waist-high wooden fence into the pigpen and crouched into a doorway slathered with a thick coat of pigeon poop. He gestured for me to follow, and the pig glared at me as I climbed in. I craned my neck inside the filthy little shack, where Yaboh stood pointing up at a corner where a black skull hung from the rafters. The lower jaw was missing, but the skull was otherwise fully intact, boasting most of its upper teeth. I waited for the magic of the moment to seize me. Outside, the pig snorted.

There wasn’t much to see inside the shack, so we went back inside the house, where Yaboh’s wife served tea. Family lore has it that the skull once belonged to a warrior from Koki who fell victim to a band of Pansar tribesmen during a long feud in the age of Yaboh’s great-grandfather. The great-grandfather didn’t take the head himself—in fact, he was known as a peacemaker and had tried to dissuade the warriors from making the raid—but he insisted that it hang in his house because he was the only one in the village rich enough to afford all of the ritual sacrifices the head would need. Now it’s up to Yaboh to keep the skull happy. “It’s not too expensive,” he said, “but it takes a lot of time. It keeps me busy.”

After a while, Thoe Set, Yaboh’s eldest son, came into the room holding a live chicken by its feet. Thoe Set, twenty-six, would assume the role of chief when his father died, and he was starting to learn how to perform all of the sacrifices and various rituals. Yaboh took the chicken gently by the neck and squeezed hard. He whispered a quiet incantation while he squeezed, thanking the chicken for giving its life for the sacrifice. When the chicken’s legs stilled, Yaboh laid it on the ground and dug its heart out with his thumb. He wrapped the heart in a banana leaf and turned for the door. “I’m sorry, but no one can watch me feed the skull,” he said.

When Yaboh returned, we ate a lunch of steamed watercress, rice, and beans. Yaboh dug out his spear and bearskin bracelet. He had a cowrie shell headdress on the wall but said it had become too fragile to put on. In his ancestors’ gear, Yaboh resembled a tourist dressed up for a photo at a theme park. He told us that he didn’t know any other chiefs who still kept skulls or practiced the old animist rituals. “I may be the last one,” he said, a note of resignation in his voice.

“The world is changing day by day,” he said, looking over at Thoe Set, “and even though I’ll try to pass on all of my clan’s knowledge, I worry they’ll forget. One day I think they’ll abandon all of the old cultural traditions, the inheritance of so many generations.” Thoe Set was packing his cheek with a wad of betel wrapped in a tobacco leaf. “But I’m less worried about them maintaining the skull and rituals than I am about making sure they know that we once had a rich, strong culture. They should know about it, and be proud of it. They should be proud that their family once owned a skull.”