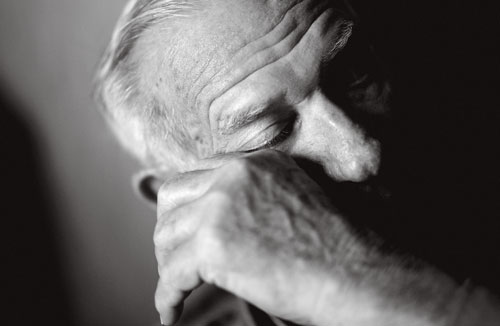

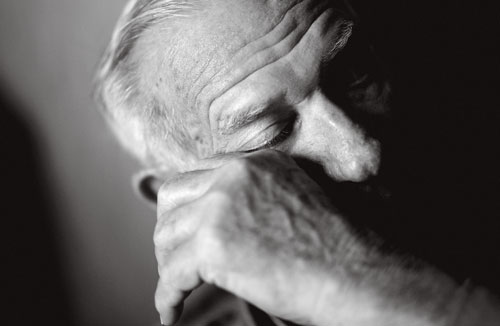

- Tom Rose wipes a tear from his eye while reminiscing about his wife who passed away. The two were married for sixty-three years, and Tom continues to struggle with her loss.

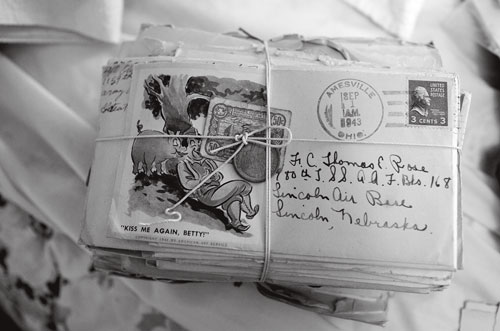

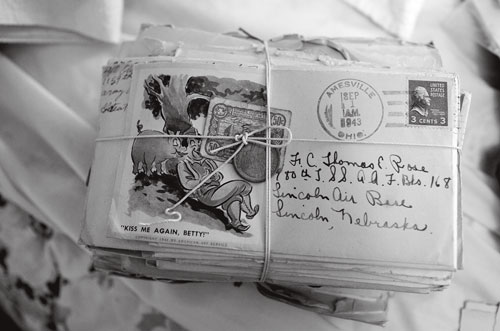

- Correspondence between Tom and his wife Mary from WWII sits tied together in an upstairs bedroom. The two were dating when Tom left for the war and married promptly upon his return.

- Tom recalls memories of his wife. “She was beautiful, just beautiful, like a model,” says Tom. “She used to work in New York, you know.”

Maisie Crow’s friendship with Tom Rose began one rainy day in the autumn of 2008 when she needed a lock for her house.

“I was waiting in line at the shop and we got to talking and I asked if I could take his portrait,” she remembers. “He invited me out to his house.”

Crow knew nothing about Tom, only that his weathered features and expressive eyes would make for a compelling photograph. When she drove out to his family farm on Canaanville Road outside Athens, Ohio, Crow discovered that the house where Tom lived was the same house he had grown up in, the same house he had shared with his wife since they returned to Ohio in 1969.

“He told me that a few months earlier he had lost Mary, his wife of sixty-three years,” Crow says. “He was having a hard time dealing with his loss, and we spent a lot of time talking about it.” Just talking brought him to tears. Tom has a look of toughness about him, like someone you would see jumping off a combine at harvest time; that tough exterior made it especially hard to watch him as, voice cracking, he spoke about missing Mary and the difficulty of adjusting to a new life without her. “It was emotionally challenging to see someone hurting so much,” Crow says.

“It was emotionally challenging to see someone hurting so much,” Crow says. “I could not have done the story with out developing a relationship with him.”

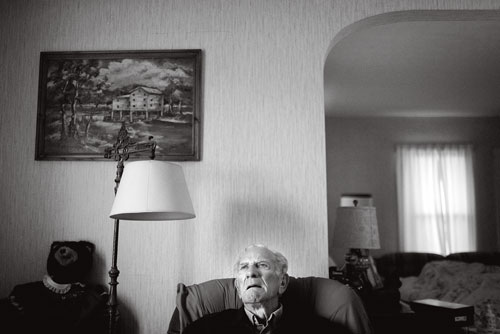

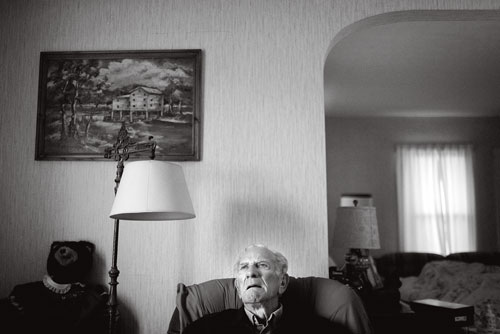

But Crow says it was not a sudden moment of realizing, “This is a story.” Instead it was a friendship. Over the next few months, she visited Tom often and gradually learned more about him. He had served in World War II. He was a salesman for thirty-one years before returning to farming. He had been a member of Lions International for over fifty years. He collected scrap metal to raise money for the blind. She also learned that Tom was visiting his wife’s grave at the cemetery on Union Street several times a month. “He said he wasn’t sleeping well and sometimes fell out of his bed when he had nightmares,” Crow says. He spent most of his time alone in the living room, the curtains drawn to block out the light. Crow saw a story that needed telling.

Every year Ohio University’s School of Visual Communication publishes a student website called “Soul of Athens”—which features stories about people in the area. With a county of just over 63,000 residents, the site not only shows off the high quality of student work, but also serves as proof that a journalist doesn’t need to go to a major city or to the other side of the world to find important stories. Crow wanted to develop a multimedia story for the site about Tom’s struggle against grief, something that would combine her photographs and video with an audio story in the vein of the PRI radio show “This American Life.”

She explained the idea to Tom. “I could not have done the story without developing a relationship with him,” Crow says. “I built a relationship and he allowed me to share his story.” She began shooting more photographs and recording their conversations. They visited Mary’s grave together. They went to church. Tom walked Crow through his home, explaining the artifacts of a long marriage and its emotions. “We remodeled it piece by piece, room by room,” he told her. There was the shag carpet they had installed together. There was furniture they had purchased over the years. Collectibles on the shelves. The clock on the mantel. Their baby pictures placed in a shared frame. “If you don’t have memories,” Tom told Crow, “you don’t have anything—because life is but a memory.”

- Tom naps on the pullout couch in the living room of his farmhouse. He has not been able to sleep in the upstairs bedroom he once shared with his wife Mary since her passing.

The statement defined the direction of the resulting audio slideshow. It ticks through stacks of Tom’s snapshots of his life with Mary and their children, and Tom’s nasal Midwestern voice, often trembling with emotion, takes us carefully through his memories. “We met at the Athens County Fair,” he says of his first encounter with Mary. “I believe it was 1940. I had seen her pass on the street where we were working. I knew nothing about her, but I liked what I saw— in a nice way.” They began dating but Tom went away to war, and they were separated for years. A thick stack of Mary’s letters to him still sits carefully tied in an upstairs bedroom. As soon as he returned stateside, they were married at a little church on Fifth Avenue in New York. “And we were happily married for sixty-three years,” Tom concludes.

But much of the slideshow can be difficult to watch. Tom hurts, and we can see it. It’s been said that photojournalists—the good ones— have the ability to keep the camera on their subjects when the human instinct is to look away. Crow’s portrayal of Tom never fl inches, but she always treats him with respect and compassion.

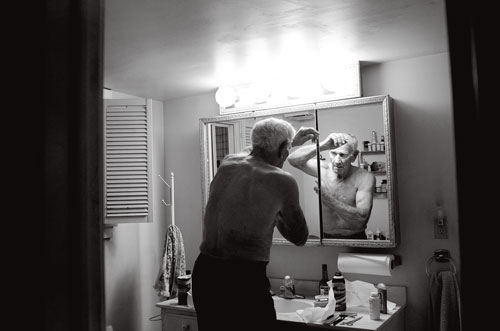

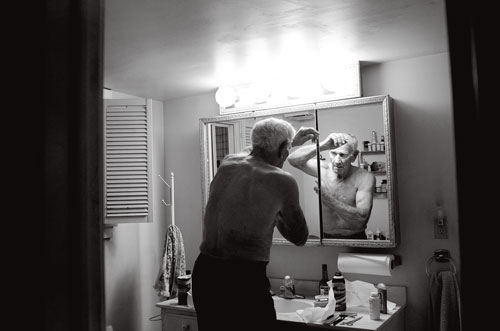

- Tom looks at himself in the bathroom mirror while putting on deodorant after a day of working on the farm.

“Death is so final. It’s like turning off a light switch,” Tom says before breaking down. Most of all, Crow never gives in to clichés or relies on platitudes, forcing us instead to confront the daily nature of Tom’s loneliness. “It’s supposed to get easier, but it better damn well hurry up,” he says, “because I can’t take much more.”

We see him sleeping on the pullout couch because he can’t bear to be in the upstairs bedroom he had shared so long with Mary. We see him trying to hang on to routine, showering and shaving before church. We see him leaned back in his recliner, adrift amid a household of memories and no one to share them with. “Everything I look at, Mary is a part of,” Tom says. “You try to live your life like you used to, but the ‘used to’ isn’t there. It’s gone.”

Crow assembled the stills, the video, interviews, and sound, then worked with senior producer Jennifer Poggi to complete the multimedia for Soul of Athens. The piece was an instant success and has since been included in the National Press Photographers Association’s Best of Photojournalism 2010 and was selected to be shown at the 2nd Lumix Festival for Young Photojournalism. The photographs, too, have landed Crow on the Emerging Talent section of Reportage by Getty Images and on the New York Times Lens blog’s list of a Dozen Promising Photographers. But the real test of the finished project, for Crow, was when we she showed it to Tom Rose. “We watched it together and we were both crying and he said it was sad, but true,” she remembers. “I can’t answer for him, but I think it was an outlet to share what he was going through.”

Devin Greaney is a freelance photographer and writer based in Memphis. His writing has appeared in the Memphis Downtowner and News Photographer, the magazine of the National Press Photographers Association.