Elephants don’t belong here.

But that doesn’t deter Amadou, a local guide who assures me that this, the barren badlands of north-central Mali, is prime elephant country. He saw them, the last remaining elephants along the Sahara’s southern fringe, only yesterday. Amadou is silent for a moment as we scan the empty horizon. A few months ago, he offers, a flicker of triumph passing across his face, a French tourist he was guiding impaled herself on a tree root while fleeing an angry elephant; she died soon after.

“But she was old and fat.”

“The elephant?”

“No, the tourist.”

We leave behind the monoliths of Hombori, rare outposts of drama atop the arid Sahel plateau, and cast off from the only paved road through one of the poorest countries in the world. In ever-widening circles, we drive through the hardy thorn scrub and a sparse sprinkling of acacia, lurching along washboard tracks before coming to a halt, becalmed, in the midst of a bleating herd of archaic, long-horned cattle.

Just because Amadou saw elephants yesterday does not mean that he remembers where he was at the time. Nor does he know where the elephants might be today. In the white heat of afternoon, Amadou, who wears a woolen hat and a heavily padded coat, has misplaced the largest land animal on earth.

Random tracks disappear into the distance. In all directions, soil with the consistency of talcum powder and skeletal trees mimic a poor-man’s mirage of abundance. To this questionable bounty of the earth’s resources has come an astonishing patchwork of West Africa’s peoples—nomads from the Sahara, nomads from the Sahel—pushed here by the Sahara, which inches ever closer from the north, and blocked by Africa’s burgeoning population to the south. Herders are everywhere; they respond to our queries about elephant sightings with waves toward all points of the compass.

At a Tuareg camp of flimsy beehive huts: “The elu-an were here three days ago. They destroyed one tent and ate two sacks of millet. We lit a fire for two days and they went away.”

At a Songhaï village where taciturn men sit in slivers of shade: “The chebe’ro were here two days ago. We don’t know where they went.”

At a Fulani camp, where children huddle in the folds of the women’s clothing: “The ni’awa hurried past at 5 a.m. They were heading north.”

At a ragged tent of the Bella, the former slaves of the Tuareg: “They were here this morning. But they went toward the waters of Agoufou.”

Then the trail goes cold.

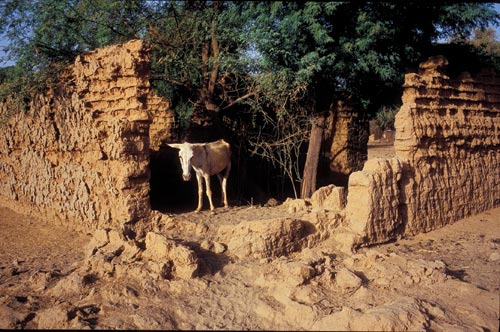

In Agoufou, a permanent settlement of cracked mud walls by a receding shoreline of stagnant water, we are assailed with as many versions of the elephants’ whereabouts, all stated with Amadou-esque conviction, as there are villagers eager to help. The elephants are in Oboko. They are by the lake. They are close. One man encountered them this morning when he went to look for his camels. Another saw them yesterday, bound for Gossi. Amadou has fallen silent.

In Oboko, a shabby fellowship of huts beyond the lake, we find another Amadou whose granary, some distance from the village, was destroyed overnight by elephants. He leads us under a merciless sun along dry riverbeds, back the way we came, bumping over rutted tracks to an enclosure fenced by hastily assembled, gossamer-thin thorn branches, where Amadou’s mud-walled granary gapes in a state of semi-collapse, strewn with millet stalks; elephant footprints and great mounds of dung lead off into the bush. “They smell the millet and they come,” he says simply. He has no money to build the cement granary that would keep the elephants at bay. Now he has no millet to see him and his family through the soudure, the hungry period, until the Sahel’s next uncertain harvest.

“Are you angry?”

“Yes, but who can I be angry with? The elephants? Being angry won’t feed my family.”

The two Amadous shrug. Neither of them, nor anyone in the vicinity, has any idea where the elephants might have gone.

The Sahel is a void, a desert in the making. If it receives rain at all, it is only for two months each year. In most years, the Sahel—an Arabic word meaning “shore,” in this case on the coast of the Sahara—receives too much rain to be a desert, yet not enough to keep the desert at bay. As a consequence, the Sahara, the youngest desert on earth, is eating away at its shores.

The inevitable and irreversible process of the Sahara’s southward march is much disputed in scientific circles. There is, however, little doubt that the Sahel’s unpredictable rainfall makes it highly susceptible to short-term fluctuations. A 1991 study published in Science magazine found that below-average rainfall between the years 1980 and 1984—one of the driest years of the twentieth century—caused the Sahara to grow by 15 percent, adding 1.3 million square kilometers to its territory and temporarily pushing the desert’s boundary south by 240 kilometers.

In the Sahel, the Sahara’s echo, it is not unusual to travel for weeks without seeing a single wild creature silhouetted against the horizon. And yet, before the Sahara began its long descent into aridity four thousand years ago, the great beasts of Africa were plentiful across both the Sahara and the Sahel. Even as late as the early nineteenth century, explorers such as Mungo Park and René Caillié (the first European to reach Timbuktu and return) reported that elephants were to be found in great numbers throughout West Africa. Mali’s elephants are anomalous relics of this abundance, of the vast elephant herds that once roamed the entire African continent, from the shores of the Mediterranean to the Cape of Good Hope in the south.

European colonial encroachment into the West African interior, an insatiable hunger for Africa’s ivory, the advent of breech-loading rifles, and a growing human population propelled West Africa’s elephant population into a downward spiral. The number of African elephants fell by 75 percent in the nineteenth century. In the century that followed, elephant territory in West Africa contracted by 95 percent as the Sahel’s human population grew from eight million to nearly forty million. Of the estimated half million African elephants that remain on the continent, just twelve thousand are in West Africa, and more than half of these live in herds of less than a hundred—outposts of doomed pachyderm life surrounded by an expanding sea of humanity.

In the past two decades, elephants have disappeared entirely from Mauritania. No more than three hundred are believed to survive in the Ivory Coast and these will surely disappear within a generation. In Mali, elephants were still present in great numbers throughout the country in the mid-1970s, but now barely five hundred—Africa’s northernmost herd—remain, here in the Gourma, a massive shallow depression close to Hombori. “There is simply little room left for elephants in modern West Africa,” wrote the eminent elephant biologist Dr. R. F. W. Barnes. “With weak economic arguments for elephant conservation, and sometimes strong economic and social arguments against (due to agricultural losses), some might argue that elephants are a luxury that West Africans cannot afford.”

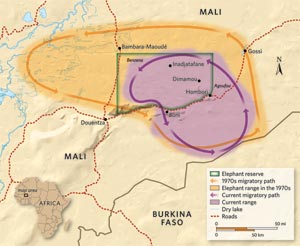

But these are not your ordinary elephants. Mali’s elephants have survived where others in West Africa haven’t because, like many peoples of the Sahel and the southern Sahara, they are nomads. In their quest for food and water, they embark on the longest recorded annual migration in elephant history, traveling up to six hundred kilometers in a counter-clockwise path. Their roaming range of twenty-two thousand square kilometers is almost four times larger than that of their nearest rivals, the desert elephants of Namibia.

Mali’s elephants spend almost half the year in the pasture lands close to Mali’s border with Burkina Faso. In January they move north, crossing the main highway close to Agoufou, after which they enter La Réserve des Elephants, a reserve that exists in name only, within boundaries known to no one; the elephants share it with an estimated hundred thousand people and more than two-and-a-half million livestock. Once in the reserve, the elephants move from one ephemeral water hole to the next as each dries out. With daytime temperatures soaring to 120 degrees Fahrenheit in May, the Gourma elephants, drawing on ancestral memory, unerringly find their way to the last accessible water source in the region, Benzena, at the western end of the reserve, one hundred kilometers southeast of Timbuktu. At the first sign of the rains, in late June, the elephants again move south, passing through the Porte des Elephants, a narrow pass through the Gandamia Escarpment, at Boni, west of Hombori.

Despite this remarkable range, the Gourma elephants have survived because of their unusual relationship with the local people. Around the campfires of the Gourma, nomads tell stories that ascribe human characteristics to the elephants and speak with awe of the elephants’ ability to find scarce water sources and the best grazing. According to the Kenya-based NGO Save the Elephants, “Many communities in the Gourma consider the elephants as a patrimony that it is necessary to conserve, as a sign of good luck, as a part of their culture, and as a source of useful by-products. There is also a perception that elephants and humans like the same areas and therefore if the elephants disappear, the area is no longer good for humans.”

But there is trouble brewing between them. During the great droughts of 1968–1974 and 1980–1985, the southern Sahara experienced an apocalypse of famine and depopulation and formerly nomadic peoples began arriving en masse in the Gourma. The droughts sounded the death knell for a nomadic way of life that had sustained the Tuareg and Fulani for centuries. They also set in motion an epochal environmental shift in the Gourma. “Traditionally, when everyone in the Gourma was nomadic, there was peaceful coexistence,” Dr. Susan Canney, project leader for the WILD Foundation’s Mali elephant project, would later write to me. But, “development agencies encouraged settlement and cultivation after the drought and that is when conflict began.”

By one estimate, two hundred new villages have appeared within the elephants’ range during the past few decades. Many of these surround the Porte des Elephants, the elephants’ last gateway to the rainy-season pastures of the south. The disappearance of this corridor—a critical “choke point” in the parlance of elephant experts—or of Benzena, the elephants’ dry-season water hole of last resort, would be disastrous for the Sahel’s remaining elephants. As a report coauthored by Canney notes, “Studies in other parts of Africa indicate that an incremental expansion of human impact reaches a threshold, at which point elephants move away. In this part of Mali, it is not clear that the elephants would have anywhere to move to.”

Time may be running out. On a visit to the Sahel in 2008, Jan Egeland, the UN Secretary-General’s Special Advisor on Conflict, described the Sahel as the world’s “ground zero” for climate change. More immediately, the good rains which fell elsewhere in Mali last year bypassed the Gourma entirely. Dry-season water holes that sustain humans and animals alike have been reduced to stagnant puddles, and goodwill toward the elephants is evaporating from the Gourma as rapidly as its water. With water holes disappearing, human populations blocking elephant escape routes, and the elephants’ survival dependent upon the goodwill and resignation of the people—especially men like Amadou in Oboko—the Gourma’s precarious environmental balance is nearing its tipping point.

Save the Elephants now warns that elephants could disappear from the Sahel within a dozen years. Or, as El-Mehdi Doumbia, a local conservationist, would later tell me, “You are watching the early signs of a catastrophe.”

Before entering the Réserve des Elephants, we circle it, following the ribbon of tarmac that marks the reserve’s southern and eastern boundaries, passing through the settlements that are tightening around the elephants’ habitat like a noose. Hour after monotonous hour, the blistered asphalt unfurls across thorn-strewn plains that possess all the charm of an overexposed photograph. Occasionally, an improbable pocket of green appears and we draw near, discovering it to be the poisonous Calotropis procera, the Apple of Sodom.

Gossi, near the easternmost frontier of the reserve, sits on the shore of the only lake in the Gourma, apart from Benzena, to survive the dry season. Prior to the droughts of the 1970s and 1980s, Gossi was little more than a seasonal camp for nomads, and hundreds of elephants visited the lake every year. Now Gossi is a permanent scar on the map, home to more than ten thousand sedentaires and untold numbers of livestock. According to Susan Canney, few elephants now come to Gossi, although a small group of males passes the dry season in the swamps south of town. As we approach, the reason elephants have forsaken Gossi is obvious: great herds of long-horned Fulani cattle wade into the shallows, obscuring the lakeshore.

We have an appointment with Toubeïssi, a local Tuareg man who passes as Gossi’s resident elephant expert. He promises to meet us at the town entrance, but then calls to say that a friend has borrowed his motorcycle and that we must go to him if we wish to meet; his directions are vague. Along Gossi’s dusty streets and potholed tracks, amid mud-walled houses and the stench of untreated sewage, small children lead us on a merry dance until, finally, we track him down. He sits cross-legged on the floor of his thinly stocked corner store. His motorcycle is parked outside.

“We have been taught by the NGOs to respect biodiversity, and that we should live alongside the elephants,” he begins, as if reading from a prepared speech. “It is one of the riches of the Malian government. The elephants do not cause problems.”

“And this year?”

“This year the rains were good, so they didn’t come so close.”

“And when it doesn’t rain?”

“They never came inside Gossi, except fifteen, maybe twenty years ago, during a drought when they came right into the main market and ate all the millet. Now they come only to the outskirts.”

“Did you see them this year?”

Toubeïssi beams. “This year was a very good year. Hundreds of elephants came to Gossi. There were so many, I couldn’t count them, even babies.”

My questions dry up. No serious elephant expert would claim that elephants still visit Gossi in large numbers, least of all in a year with so little rain. We bid each other an awkward farewell.

Baba, my driver, and I enter the reserve north of Hombori.

“The elephants, they were here last night,” he says by way of introduction. “They ate the crop of one man. Now they are thirty, perhaps thirty-five kilometers away.”

The Gourma is wild, desolate: white soil, a white wind, and dead branches silhouetted against a bare, unforgiving sky. But in these days of creeping environmental catastrophe, the Gourma’s wildness is of a very modern kind, inhabited beyond its limits by people and livestock who live here because, like the elephants, there is nowhere else for them to go.

At Dimamou, a litter of straw huts inhabited by malnourished children, we take on Moussa Dicko, an elderly hunter turned elephant guide. “The elephants, they were here last night,” he says by way of introduction. “They ate the crop of one man. Now they are thirty, perhaps thirty-five kilometers away.”

We set off across the low sand hills that cover half of the Gourma, passing ragged settlements within sight of distant cattle herds, crossing clay pans white as white, and negotiating the eroded banks of seasonal riverbeds, now dry. The going is slow.

“What do the people of Dimamou think of the elephants?” I ask Moussa, shouting to make myself heard above the straining engine.

“People like the elephants because we have learned that we can make more money from them than from anything else.”

“That’s you, a guide, but what about ordinary people?”

“They also think it’s a good thing. I give them tea and sugar, so the money goes to all the village.”

“And before the tourists came, what did people think?”

“The government used to give us money to plant trees for the elephants, so people were happy with the elephants.”

“And before this?”

“For the nomads, the elephants were our guides. When people saw the elephants, they knew there was food and water. The elephants eat the tops of the trees, the goats eat the bottom.”

Two hours after leaving Dimamou, we arrive at a long line of trees where cattle and goats mill about in clouds of dust. Clusters of trees, usually rooted in seasonal standing water, are what pass for plenty in the Gourma, and they serve as the dry-season lifeblood for elephants, humans, and livestock alike. We stop a few hundred meters away. Moussa approaches on foot, talks to the herders, and then disappears into the undergrowth. We wait.

Time passes. Young men, boys really, wander over to surround the car, a clutch of dusty turbans, dark, weathered faces, and gray robes; they watch without a word, asking for nothing. From the west, astride a camel, a sinewy old Tuareg nomad comes cowled in robes of indigo and bearing an ancient rifle; he grunts in greeting. He speaks only Tamasheq, and Baba makes small talk. Respectful, Baba is reluctant to translate their conversation, but I insist. He asks the man if he knows the name of Mali’s president. “Modibo Keita.” Baba chuckles. Mali’s first post-independence president, Modibo Keita was overthrown in a coup in 1968.

After an eternity, Moussa returns: The elephants are deep in the forest. We drive around the northern perimeter and walk into the undergrowth through crater-sized footprints; the open spaces of the Gourma disappear from view. The snuffling of cattle accompanies our passage into the interior, and Moussa pauses from time to time to listen amid the clatter of hoofs and to inspect fallen leaves and piles of elephant dung. Over there, suggests a wary Fulani herder, indicating vaguely to the south. “No,” whispers a reticent Tuareg man in robes of vivid blue, “they are moving east.”

Without warning, an elephant’s cry of alarm draws the landscape to attention, bringing the forest alive. We crouch, waiting for the elephants to reveal themselves.

For two hours we creep through the forest, circling west, then south, then east, finding neither elephants nor the water that draws them here. We are tired, thirsty, and no longer excited, and there comes a moment when, surrounded by cattle, we both know that the spell has been broken. No longer whispering, we decide to return to the car until, on the forest fringe, Moussa becomes suddenly alert: he has heard something. We set off quietly, heading east.

The forest stirs. We creep forward, aware of the sound of our footsteps, stop to listen, then creep again, moving farther into the forest. In an instant, the wind, and with it, something intangible, shifts. Moussa, too, has sensed it; he has frozen in mid-step, eyes scanning the undergrowth. There is no sound, save for the ringing silence of the African wild. Then, with a barely discernible sideways flick of his head, Moussa indicates a flimsy wall of branches just twenty meters away. Behind it, an immobile gray form fills the negative space like a pale shadow in this late-morning forest drained of color. Through the scrub, I glimpse an eye, haunted and melancholy, watching. We wait, humans and elephant, holding our collective breath, too close. Moments pass, until, unable to bear the suspense, the elephant takes a step toward us, ears flared in threat display. We run. Behind us, with a great noise like a tree falling, the elephant wheels away and is gone.

We return to the car. I chatter excitedly, eager for more. But Moussa is breathing heavily and points Baba in the direction of Dimamou, his job done. He is an old man, he explains, no longer up to hours spent walking in difficult country. We are well on our way when, more out of a sense of duty than any real desire to find more elephants, Moussa waves Baba over to a young Tuareg herder and asks perfunctorily if he has seen the elu-an. “They fled at the sound of your engine. They are right in there.” Moussa sighs, but sets off nonetheless, limping into the forest.

And then, just like that, there they are, gargantuan shapes moving like a cloud shadow across the landscape. Six females lead this elusive troop through the thorn scrub, gathering infants—splendid, absurd little creatures—around them as they go. One adolescent pauses long enough to spray herself a dust bath. Another, perhaps the matriarch, swings her trunk from side to side, gently shifting her weight and maintaining momentum, before moving off again in fluid silence. In perpetual motion, in no great hurry, these giants walk with infinite, languid grace deeper into the forest. We follow in their wake, spellbound, knowing that we cannot follow, unable to let go.

I have seen elephants before in the wild, most memorably in immense congregations of hundreds in Zakouma National Park, in Chad’s south. Like the great herds of ancient Africa, they rampaged across the land in all-conquering hordes, epic in scale and masters of their isolated and thinly populated corner of the continent. But here in the West African Sahel, the elephants move in small furtive bands of fugitives, summoning their families around them and seeking refuge in the meager shade.

These elephants should not be here. Their time, after millions of years of inhabiting the Sahel, has almost certainly passed. If the predictions of elephant experts are accurate, some members of this small family will die before the next rainy season, and if not these then others of their kind, dotted in isolated small tribes across the Gourma. Even if they make it through the year, then, harried by mankind and stalked by a drying climate, these may represent the last generation of elephants to survive the Sahel, another wild thing disappearing from wild places, another symbol of our time.

The Gourma’s farmers, subsisting one bad year away from starvation, would doubtless not mourn their passing. And yet, as the herd searches for a way through the trees, I hear the words of V. S. Pritchett: “If the elephant vanished, the loss to human laughter, wonder, and tenderness would be a calamity.” There is something about elephants—their melancholy wisdom of ages, their unearthly gravitas—that stirs the soul. Even Moussa looks on with unabashed wonder.

And then they are gone, leaving in their wake an empty silence, as if the world had been held in abeyance to mark with respect the elephants’ passing. Slowly the birdcalls resume. A distant herder’s cry penetrates the trees. Cattle shapes draw near through the scrub.

We travel deeper into the reserve, reaching Inadjatafane at nightfall. The largest settlement within the reserve, Inadjatafane is one of the tidiest villages I have seen in Africa: mud-brick houses arrayed along broad sandy streets on the shores of one of the largest seasonal lakes in the Gourma. But for all its appeal, Inadjatafane is a sign of troubled times. Topographic maps of the Gourma dating from the late 1950s show only a stand of trees labeled “Tin Adyatafan.” If there was a settlement at the time, it was restricted to seasonal Tuareg tents. Now, Inadjatafane is home to around 2,500 Tuareg, Bella, Arab, and Songhaï inhabitants, irrefutable proof of the Gourma’s shift from a largely nomadic world to a settled one.

Inadjatafane is also home to El-Mehdi Doumbia, the local point man for Mali’s Direction Nationale de la Conservation de la Nature. A quiet man, El-Mehdi embodies the stillness and calm authority of a man who has spent two solitary decades working for wildlife conservation in the Gourma. According to Susan Canney, El-Mehdi is “in a league of his own in terms of elephant knowledge.” His intimate understanding of the Gourma elephants is marked by his gnarled hands, broken in the past by an ungrateful elephant that El-Mehdi helped rescue from a muddy pit. And the vast geography and fragile fault lines of his country run through his blood: his father was a black Bambara from the south, the traditional rulers over the country; his mother a Tuareg from Kidal, a people and a region that, even today, wage rebellion against what they see as a foreign government. For all that, he is a man at peace with himself.

We talk in El-Mehdi’s swept-sand courtyard, empty save for a colossal elephant skull leaning against a wall.

“This year is one of the worst years I can remember for the rains, because almost all the lakes are running dry. At the biggest lake, Benzena, it is possible that there will be no water in May. The last time it was this bad was in 1985, when Benzena ran dry. Hundreds of elephants died like flies. The government had to send trucks with water.”

Later, Ousmane Dicko, a tea shop owner and part-time elephant guide in Bambara-Maoundé, on the western boundary of the reserve, will tell me that so many newborn elephants died that year en route to the Niger River, some eighty-five kilometers from here, that they “were eating baby elephant meat for weeks.” Colonel Biramou Sissoko, the Director of the World Bank–funded Projet de Conservation et de Valorisation de la Biodiversite du Gourma et des Elephants, will also warn: “This year, the danger is that, if nothing is done, many elephants will die, and people too, because the elephants will surely go beyond Gourma to the Niger River, like they did during the drought in 1985.”

Back in Inadjatafane, El-Mehdi worries: “If they don’t make the right decision this year, it will be worse even than in 1985. As Benzena is always the last, all the elephants will go there. There may be water in Gossi this year, but in the last decade, many babies were born and many elephants only know the way to Benzena. And anyway, they won’t go a hundred kilometers to Gossi. Gossi is now a big town—there is no place for the elephants. Where will they eat? Where will they rest?”

“If there is not enough water in Benzena, what will happen?” I ask.

“It doesn’t bear thinking about. First, when there is less water, more cattle go to the lake and there is no room for elephants. Secondly, when there is no water, nomads dig wells and carry the water to camp in containers, so the elephants attack the donkeys to get the water. And third, there is a big group of elephants here, close to Inadjatafane, and many nights they come into the village, following the smell of food, and they attack shops and stores and crops. One man this year has already lost his entire crop. Things like this will become normal.”

“Are the elephants dangerous for the local people?”

“People have been killed by elephants many times: one man four years ago, two years ago a mother and baby, in 2000 a young boy. If things don’t improve, more people will die.”

I can scarcely see El-Mehdi’s face in the gathering dark.

“But don’t the local people and the elephants have a special relationship?

“All the stories you have heard about the elephants are true. If the elephants don’t appear in Benzena, the nomads know that they have gone to water, so they go off to find them. Until ten years ago, everything was fine. There was no problem between the nomads and the elephants. But now the rainy seasons are getting worse and elephants and people are coming into conflict.”

He pauses, drawing his coat around him to ward off the evening chill, shivering slightly.

“The greatest threat to the elephants is not from people and vice versa. The problem is the changing climate. Now the people and the elephants are going in greater numbers to the same place and there is not enough water.”

“What can be done?”

“The only solution is to move people from Benzena, to where there are wells, and leave the lake for the elephants.”

El-Mehdi has a report to write, by candlelight.

“Tomorrow you will go to see the elephants, but tonight, wherever you are in Inadjatafane, you will hear them.”

-

- Wells and water carried in hide containers are lowering traditional waterholes to dangerously low levels.

El-Mehdi entrusts me to the care of one of his young protégés, Shitta al-Mokhtar, a lean, light-skinned Tuareg man from a noble family. With his boyish smile, Shitta is as eager as El-Mehdi is patient. He worships El-Mehdi and steals careful glances at his mentor as he speaks; El-Mehdi smiles benignly. We set up my tent in Shitta’s empty compound and talk deep into the night.

“I have never been to school, but I have grown up around the elephants,” Shitta tells me as he boils the tea, ripening the leaves slowly over the coals. “When I used to look after my animals, my cows were sometimes among the elephants. For us, it was normal. We learned about the elephants, but it was not for the tourists. It was to know which elephants were dangerous. Everything I have learned did not come from any book. I learned by watching them.”

A goat wanders into the yard calling for its owner who, according to Shitta, ran home in fear when elephants drew near to the lakeside at dusk.

“In 1999, I was looking after my family’s animals. I was on a camel. Until 3 p.m. I didn’t pray, so I stopped to pray. Suddenly my leg became paralyzed as I was getting down. I tried to get back on my camel, but it ran away with all my food and water. For three days I stayed there. At midday on the fourth day, my leg recovered, but I no longer knew where I was. I was very thirsty. I saw an elephant and it came close. It moved its trunk on the ground, this way and that. Then it turned around and walked away. I followed. When I stopped, it stopped. When I walked, it walked. It led me to a well. I stayed in the water and drank for an hour. The elephant ate at the trees nearby. A hunter came with a camel, and the elephant charged until the man and his camel ran away. Then the elephant left. I was hungry, and I walked and walked until I found a Tuareg camp. They had found a camel with my food and shoes. I looked and looked but I never found my animals. Finally, I decided to return to my family at Inadjatafane. Since that day, I have devoted my life to elephants, to being a guide, because an elephant saved my life.”

An elephant barks from across the lake.

“I want to be close to elephants all the time,” Shitta continues, talking very quietly in that African way of respect, with eyes downcast, his face aglow in the firelight. “I am very fond of them. Where they move, I will move.”

I love sitting here in a village without electricity, around a fire, listening to stories about elephants in Tamasheq, the sound of scalding tea being poured from pot to glass to pot. There is nothing I like better. Shitta serves the first tea, a bitter brew strong enough to fortify a camel. He talks softly, telling elephant stories, regaling me with tales of close encounters and the curious ways of elephants. He explains that in Tamasheq “afous” means both “hand” and “trunk,” that the elephants “pass through the forest like a snake, slow and quiet,” that they play like children. “Five days ago, I was in the forest and came upon an elephant with a baby. I tried to hide behind a tree, but the elephant circled the tree and I knew that I could not escape. So I untied my turban and hung it from the tree. The elephant was distracted and tried to attack the turban. I ran away. I still don’t know what happened to my turban. I didn’t dare to go back.”

Shitta falls quiet as the fire crackles and spits. He serves the second tea, a tea of sweetness, an antidote to the necessary fortifications of the first, with the sugar dose raised almost to half.

“There are twenty elephants that come to Inadjatafane with the others, but they don’t go to Benzena with the rest. They stay here after the first rains, the second rains, and only go with the third, when they travel to Boni to meet the others. They all arrive at the same time, as if they had an appointment. But one male, he stays until much later. And while he is here, adults cannot approach him, but small children can go right up to him and he will not do anything. Then, very late, he goes down to Burkina Faso to call the others.”

The third tea is sweet and lightly laced with mint, a reward at day’s end. Around Tuareg campfires all across the Sahara, this final glass (although more will be offered) induces conversation, an accompaniment to storytelling and news brought by travelers.

A villager enters the compound and whispers in Shitta’s ear.

“The elephants have entered the village.”

I sleep fitfully amid the intermittent clamor of the African night. At 5 A.M. a full, precious half hour before the appointed time, Shitta arrives. He was so excited that he couldn’t sleep. I am excited, too, but the sun will not rise for another two hours; I emerge from my tent grumbling. Unperturbed, Shitta prepares a breakfast of yesterday’s bread and chatters cheerfully about the day ahead. We set off in merciful silence.

Sunrise in the Sahel. Apart from the hour before sunset, this is the only time of day when the Sahel is beautiful. A gentle sun bestows the day’s first color, burnished orange, to dust bowls before shortening the long shadows, brushing the landscape with warmth and contrast as a precursor to setting the earth ablaze. In the lifting gloom, every tree on the horizon looks like an elephant.

By now, our searching has taken on a familiar rhythm. We drive across a flat, pebble-strewn landscape, pausing to ask villagers outside seasonal straw huts if they have seen the elephants. It is rare that they have not. Having fed overnight on the gardens of Inadjatafane, the elephants have retreated north, looking for a place free from human settlements. We follow in their wake, guided by the villagers’ wary whispers.

Ten kilometers from Inadjatafane, where a plateau of sand and clay surrounds a broad expanse of low trees, Shitta orders Baba to turn off the engine, and we walk. A few hundred meters from where we enter sparse forest outskirts, fifteen elephants graze quietly and without fear, lingering in open country but already preparing to enter the forest cover where they will pass the day, only to emerge in the cool of evening when very few humans will be out. Among the herd are babies and adolescents; yet to acquire the effortless grace of their parents, they nod earnestly as they walk, unaware that they are perhaps the most vulnerable elephants in Africa.

That the Gourma elephants are fearful of humans reflects a learned need to protect their young.

Baby elephants can usually stand unaided within an hour of birth and are able to join a herd’s movements within days. But these infants, if they live, will cover hundreds of kilometers in the next few months. The daily demands of life in the Gourma—the harshness of the Sahelian environment, the widening distances between water holes and between water holes and pastures, and the length of the annual migration—especially affect the young. As a result, infant mortality is high and the Gourma’s proportion of adult elephants—more than half—is one of the highest in Africa. Even in good years, according to El-Mehdi, “more babies die than live.”

That the Gourma adults are fearful of humans reflects a learned need to protect their young. In the early seventies, during the drought, twenty baby elephants reportedly died of thirst and exhaustion after being pursued for three days by camera-toting tourists. Another infant died more recently, close to Benzena, under similar circumstances. Even without tourists, in desperate years such as this one many of these babies north of Inadjatafane will likely die.

Still unaware of our presence, the elephants edge deeper into the forest. The adults seem to glide while walking, moving faster than a running man; the infants’ heads bob as they struggle to keep up. From time to time, the elephants pause to rest, or to strip a branch of its leaves, or simply to stand in stillness. At one such moment, a baby hurries to its mother and makes as if to drink, but the mother stirs and continues on her way, her young drawn close.

I could watch these elephants forever, but Shitta signals that we should leave, lest we disturb them. We inch away, but Baba, eager that his paying client not walk too far, revs the engine and comes to pick us up. Shitta is furious. When we look back, the elephants are long gone.

We shadow the forest fringe to the north and then west, passing small stagnant ponds. The further we go, the more Shitta’s mood darkens as he mutters, again and again, “Normally at this place, at this time, there is water.” With desultory gestures, he guides us to a desiccated elephant carcass, a great bag of bones lying as if in flight, its exposed ribcage bleached white by the sun. Rigid shards of skin protrude at rude angles and there are caverns where its tusks once grew, great empty pools of darkness where its eyes once were. Reading my thoughts, Shitta assures me that the elephant died not at the hands of poachers but of natural causes, and that El-Mehdi removed the tusks for further study.

“It was pointing the other way,” Shitta says, “but other elephants came and turned it around. We don’t know why.”

Close to the carcass, we enter the forest. Shitta is nervous, for we must cross treeless stretches and he knows that an encounter with a frightened elephant in open country rarely ends well. Shapes move beyond the trees, shifting shadows of elephants. As ever, they are moving deeper into the forest, toward a place which locals call “the place of the small dunes.” From a thin shelter, we watch as they mill around, pushing nose-to-nose in patient play, one resting his trunk on his playmate’s back. Shitta, who cannot remain angry for long in the company of elephants, whispers excitedly, trying to identify the elephants he knows. Then, suddenly solemn, he urges us to move on, before a sudden shift in the wind announces to the elephants that we are here and disturbs their hard-won moment of peace. We leave, reluctant and vigilant for any lagging elephants between here and our car. There are none but, turning for one last look, I see an elephant, far away to the north, separated from the herd, motionless. He watches us go.

On our last day in the Gourma, we drive a well-worn track that heads west, past columns of cattle and the vehicles of smugglers, to the lake at Benzena, the outermost limit of the elephants’ range. Beyond Benzena lies the new graded road between Douentza and the Timbuktu ferry, a track that has brought traffic and people and life to towns like Bambara-Maoundé, further enclosing the elephants within their central Gourma range. For miles around, seasonal camps that threaten to become permanent villages have colonized the sand hills that rise up from Benzena to the north, while vast herds of livestock, larger than any I have seen here, mill around the water’s edge. The shoreline is a long way from where it should be and the hard-baked mud is riddled with thousands of hoofprints.

In normal years, Benzena must accommodate a massive population of nomads, livestock, and elephants for only two months at the end of the dry season. This year, with January water levels at their lowest in decades, it will be six months before the next rains—yet the Benzena population has already swelled well beyond sustainable limits. To this intolerable pressure must be added evaporation, which, according to Colonel Sissoko, removes more water from the lake than animal and human populations combined.

The government’s response, implemented by men such as Sissoko, is to pump two hundred cubic meters of water a day into the lake, in an attempt to maintain current water levels. Due to commence soon after my visit, it seems like a simple solution, one that will keep thirst and mass starvation at bay for a time. What it won’t keep at bay is the desert. Worse still, it may even hasten its march. Pumps increase the dependence of herders and cattle on Benzena, and encourage settlement and agriculture in the area’s marginal soils. In the long term, overgrazing around the lakeshore will strip the landscape of vegetation and, as has happened across the Sahel where ground cover has disappeared, the soil will be unable to resist the relentless sun and scouring wind. The result elsewhere, in the words of one report on the Gourma, has been that “each borehole became the center of its own little desert.”

Why this matters for the elephants (as it does for domestic livestock) is that all animals require not just water, but also adequate pastureland nearby. Susan Canney, who advocates a policy of no new wells or water pumps in the elephant range, warns that “vegetation degradation around the lake risks meaning that there will not be enough food for elephants to last the dry season and they could die of starvation as they did in Tsavo in the 1970s,” when a significant proportion of the elephant population in the Kenyan park died during a drought, not from thirst, but starvation.

Colonel Sissoko himself acknowledges, albeit indirectly, that this year’s solution may be next year’s catastrophe: “Benzena is the critical point. If we have the resources, we can create pumps for the nomads all across Gourma. And then Benzena can be left to the elephants. But to do this, we need millions of dollars.”

And yet, even as human and animal populations increase, even as the soil unravels and turns to sand farther and farther from the Benzena shoreline, there remains an assumption that the elephants will endure simply because they always have. “Elephants are very clever,” Colonel Sissoko insists. “Somehow they always survive.”

There comes a time, however, when a biological limit is reached, when the water dries up, or when the distance between water and pasture stretches too far, as it surely will—if not this year, then a few years from now. And when it does, it will be too late, for humans and elephants alike.

The elephants are yet to arrive in Benzena, but they are on their way now. Will there be anything left for them when they get here? It doesn’t matter: they have nowhere else to go.