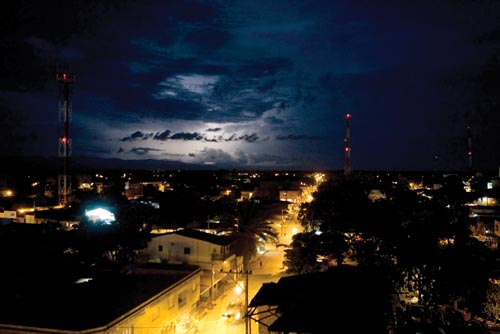

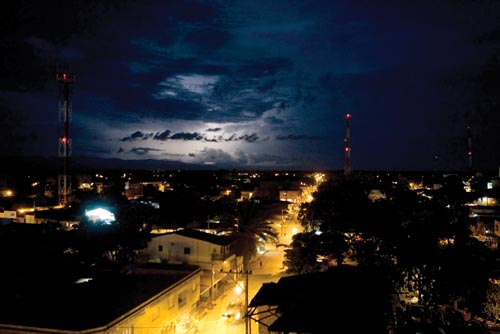

- A lightning storm over the town of Turbo, the center of banana and plantain production in Northern Colombia. Turbo is also the main port of departure for cocaine headed to the United States and Europe, a city still in the grip of paramilitary and smuggler activity.

Colombia, June–August 2007

When the trumpet sounded,

everything was prepared on earth,

and Jehovah divided the world

among Coca-Cola Inc., Anaconda,

Ford Motors, and other corporations:

The United Fruit Company Inc.

reserved for itself the juiciest piece,

the central coast of my own land,

the sweet waist of America.

—Pablo Neruda, “The United Fruit Co.”

Our flight from Bogotá to Apartadó headed north along the great verdant spine of the Andes. Flying over Medellín, a city of brick high-rises surrounded by mountains, you can look down onto the cocaine mansions and see if there is anyone in the pool. All of the country’s cities have growing slums on their peripheries, filled with war-displaced peasants and the dispossessed looking for work. Neighborhoods lit with a single bulb. Corrugated metal roofs on rough shacks lining red-dirt roads. The inhabitants of the poor barrios are the refugees from a war that has lasted more than forty years. White veils of clouds drifted over the ridges as we landed in Medellín then took off again a few minutes later for Apartadó. From the air you want to buy a parcel, you want to get in on all that beauty. We flew down out of the cool air of the Andes toward an airport that was nothing more than a few lines of asphalt cut out of the bright green banana plantations. The plane touched down and we were in the belly of the organism, but we didn’t know it yet.

When the beat-up taxi pulled away from the airport onto the shaded road, the air pouring through the windows was rich with the smell of wet earth and rotting leaves. Black men walked slowly through the fields with machetes. Most are the descendants of African slaves, and they still get the jobs that keep a man out in the sun. Spanish colonists brought the ancestors of these men here and worked them until they simply gave out.

Today, the banana region exports hundreds of millions of dollars of bananas and plantains, but the workers at the bottom of the export pyramid have little to show for it. They live in the slums at the edge of town, such as barrio Obrero, where paramilitary groups targeted them in the late nineties and murdered them in their homes. During this time of extreme militarization in Urabá, anyone suspected of labor activism or sympathy with the leftist rebels was at risk of being assassinated. The Colombian military let the gunmen work without interruption. “We patrolled side by side, fighting the guerrillas,” a former paramilitary fighter told me over beers a few days after we arrived in town. “Sometimes we traded with the army. We gave them hostages in exchange for ammunition.” Paracos (as the paramilitaries are known), their hair cut short like a soldier’s, would come for their victims on motorcycles. They called it grabbing someone. It didn’t matter what you said to them; when the paracos grabbed someone that person always died, and it was always the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC) that did the grabbing. In 2004, AUC leader Salvatore Mancuso negotiated a ceasefire with the Colombian government and surrendered to authorities at a demobilization ceremony that December. Not all of the blocks demobilized, however, and some of the old AUC groups are still actively looking for new recruits.

As the taxi clattered out of the green labyrinth and into Apartadó, there was no welcome sign, but were there one it should read, founded by united fruit, 1963. before us, there was nothing. population x. Apartadó was just a small village before the company arrived, and likewise Turbo to the east. The banana-growing region was a marshy stretch of coast near Panama with a few indigenous people, and that was all. Then United Fruit, one of the most powerful companies in the history of the Americas, transformed this section of Colombia, remade it in its own protean image and then left it behind.

- A couple walks through the barrio Obrero in Apartadó. The neighborhood, formerly a farm, was occupied several years ago and the land taken away from its owner. Most of the families who live there today work in the banana industry. During the nineties, the neighborhood was the scene of several massacres staged by the FARC and paramilitary groups who fought for the control over the industry.

* * * *

Americans did not always eat bananas. In fact, the tropical staple only came to the nation’s table through an act of desperation by a Brooklyn railroad speculator named Minor Keith. In 1871, Keith went into business with his uncle, Henry Meiggs, to build a railway from the Costa Rican capital, San José, to the port city of Limón. It was, by all accounts, a miserable undertaking. Italian workers mutinied over the conditions, and inmates from Louisiana prisons were brought in when no one else would do the job. Most of them died—as many as five thousand—trying to complete Meiggs and Keith’s project, an enterprise that was already unpopular and strangled by debt when it finally reached completion in 1890.

Not longer after the railway began operations, it quickly demonstrated itself to be a losing proposition for passenger transport, but Keith wasn’t ready to give up. During the construction of the railway he had started planting banana groves—to feed his workers—on government-ceded land near the tracks, so he decided to try his hand at the export business. He moved his trackside bananas to the port at Limón for free—he already owned the train—and freighters sailed with the fruit to the United States, where Keith sold it for a hefty profit. Soon, his banana gamble was worth more than the railroad. In 1899, on the eve of the twentieth century, Minor Keith merged his United Fruit with Boston Fruit, famous for its giant fleet of white ships, and “the octopus”—as the company is known among Latin American journalists—was born.

Soon its tentacles reached into the governments of Guatemala, Honduras, Panama, and Costa Rica, and manipulated the political establishment whenever its interests were threatened. And the company, with its acquisitive genius, kept branching out into new enterprises whenever the need arose. In 1901, United Fruit took over the postal system in Guatemala, and in a number of other countries it controlled the railway systems and the telegraph lines. A CIA-engineered coup codenamed Operation PBSUCCESS overthrew Guatemala’s elected president in 1954, when United Fruit’s business interests were threatened by new land-reform laws. The company wielded unprecedented power in Latin America, growing into a transnational entity whose appetite for resources drove the politics of the entire region.

By the twenties, United Fruit also had transformed small villages such as Santa Marta, along Colombia’s Caribbean coast, into booming industrial centers. Workers flooded into Santa Marta from distant places at a time when paying jobs were scarce. By the decade’s end, however, newly elected liberal representatives and labor leaders criticized the company and the tax-free export deal it had brokered with the government. In 1928 workers went on strike, paralyzing the company. In response, the right-wing government of Miguel Abadía Méndez called out the army, which promptly sealed off the streets to a plaza full of assembled civilians in Ciénaga and opened fire. It was a massacre that Gabriel García Márquez would immortalize in One Hundred Years of Solitude.

After the killings in Ciénaga’s central square, the Abadía Méndez government was voted out of power and the company found its business interests threatened. United Fruit needed a sympathetic national government to guarantee its profits, and that government had just vanished. United Fruit did not control Colombia as it did the Central American nations, so it was forced to make deals with the workers. Between popular liberal politicians, who now openly supported labor unions against the company, and the disruption of shipping caused by the Second World War, the octopus slowly withdrew from Santa Marta, selling its land back to the national land-reform agency at a good price, saving the company from having to abandon its assets. It was time to move on.

In 1963, United Fruit found what it was looking for in Urabá, a long-neglected but well-watered Caribbean region of Antioquia, Colombia, closer to Panama than Santa Marta. It was perfect. In the nearby fishing village of Turbo, United Fruit then repeated its well-worn and successful pattern. The company found an underdeveloped stretch of coastline, offered to build a port and bring in jobs in exchange for export concessions, then hung on as long as possible in the face of violent uprisings and popular discontent. What they tried desperately to avoid was the labor unrest that set them back in Santa Marta in the early part of the century. To get around it, United Fruit created an entirely new system of production. It was brilliant; they would create a virtual banana operation.

The big innovation was simple—the company wouldn’t own land at all. If United Fruit owned land, the workers would agitate against them. Instead, Colombian growers would own it and sell their entire crops to the company as contractors. United Fruit put ads in the paper looking for investors and got people who had never worked on a farm in their lives. Dentists and doctors suddenly became ranchers in Urabá. It was a gold rush for cheap land and the promise of big profits with the octopus. To get the growers started in business, the company handed out big development loans to the new arrivals from Medellín who proved they could cultivate bananas. With the loans and the contracts, the company locked the growers into an exclusive arrangement, and for the next five years, 100 percent of everything grown in Urabá went out on United Fruit freighters at the price the company set. Meanwhile, another conservative government in Bogotá promised to hunt down leftist dissenters and hold back the tide of Communism in the hemisphere, a crackdown that would have terrible consequences for the country. In 1966, three years after United Fruit arrived in Urabá, a group of liberal intellectuals that the government had been chasing across the country founded the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), and Colombia plunged headlong into forty years of civil war.

- Small growers receive $6 for each 45-pound box of plantains they harvest, but they must pay for all packaging, so the cost falls to roughly $3.50 per carton, a small fraction of its value in the United States. This fruit is then resold by the Colombian agricultural corporation Banacol to Chiquita brands and Dole for delivery to the US market. Chiquita sets the prices with Banacol through a long-term contract.

It was bound to happen. In the 1980s, Communist revolutionaries arrived in the banana fields of Urabá after a period of calm and high profits for United Fruit. The promise of the rebels was electrifying and straightforward: “You are poor, the company is rich, and this land could be yours if you are willing to take it.” Of course, this was nearly the same promise the company dangled before the growers. Groups such as FARC successfully infiltrated the unions and kidnapped the managers of the farms. But profits continued to climb; Urabá looked like a good investment for the company except for the violence, which accelerated steadily into the 1990s. Then, in 1997, the AUC arrived in force and offered to solve everyone’s problems. One of the first items on its agenda was to meet with company officials.

The company, in the meantime, had changed its name from United Fruit to Chiquita, a deliberate reincarnation in the form of the smiling, banana-form woman that the firm hoped would distract the public from its dark history.

- Luz Mari Pallares weeps as she shows a picture of her brother who was killed by AUC gunmen. Jose Pallares was a union leader and administrator of a banana plantation in Currulao, Colombia, when he was assassinated in October 1996.

* * * *

Carlos, my photographer, had arranged for us to meet with Captain Jaime Garcia of the Guardacostas in the port of Turbo. Captain Garcia offered to take Carlos out on a drug interdiction patrol on one of his fast boats, and now I’d been invited along for the ride.

“This could be bullshit,” Carlos said, looking around for the bus to Turbo.

“It could be interesting,” I said.

“I am thinking it could be total bullshit, you know, a pony show.”

“A dog and pony show.”

“Exact.”

* * * *

We caught a packed buseta from Apartadó to Turbo with thirty other Colombians and watched the banana fields roll by for an hour, all carefully cordoned off by barbed wire. Banana trees with broad flop-eared leaves and their unpicked fruit hermetically sealed in blue plastic, the trees growing a prepackaged product for the American buyer which comes without blemishes or bruises. Once we hit the end of the line, the driver took us out to the military base where the captain was waiting for us in the sun.

“You guys came in that?”

“Yes.”

“That’s a weird-looking taxi.” The captain laughed.

Our bus driver turned out to be an informant who told everybody, including the demobilized paramilitaries, that two foreigners just showed up at the Guardacostas station. There was no way to hide from it, the whole town knew who we were from the moment we landed.

Captain Garcia took us inside the severely air-conditioned office and introduced us to his men. The captain treated us to an American-style PowerPoint briefing, cataloguing the tons of cocaine intercepted every year by his crews. Dozens and dozens of tons according to the slides. A respectable amount but still a fraction of the hundreds of tons of cocaine that make it through. Carlos talked about his time in the jungle photographing the FARC and unnerved the captain with his extensive knowledge of cocaine smuggling. Captain Garcia conceded that there was really no stopping the drugs, and there hasn’t been. According to the DEA, the quantity available in the United States has not dropped since the advent of the Plan Colombia, the multibillion-dollar eradication program. Colombian production actually went up during a period of intense spraying and military actions: the growers just moved to different parts of the country. Who is behind the trade? Although the FARC is involved deeply in the business, it is the right-wing AUC that worked closely with the cartels to organize the smuggling system. Coca growers, who are usually poor peasants or campesinos, earn the least of all.

As the cocaine flows down the Atrato River into the Gulf of Urabá, it eventually makes its way toward the US and Europe through a network of shifting routes. The drug traffickers send the drugs overland through Mexico, as well as by sea with stops in intermediate countries. At each stage, the value of each pure kilogram increases, and by the time it reaches the United States the street cost has reached as much as $100,000. The more varied the routes, the lower the risk to the trafficker—a system that rewards creativity with millions of dollars. Captain Garcia’s job is to intercept these shipments in the Gulf of Urabá in an American-made fast boat called Midnight Express. Smugglers also use their own fast boats to move the cocaine, sealing the kilogram bricks inside small custom-built fiberglass hulls. At the destination, they remove the cargo and destroy the boat. On his base, Garcia keeps a haphazard museum of these intercepted lanchas, their hulls ripped open.

The Midnight Express is a steroidal machine, and it has a drug-runner feel to it, even though in its normal configuration the boat is sold as a half-million-dollar fishing vessel. It is a mystery why anyone would need a thousand horsepower to go catch sea bass and marlin, but it is great for going fast. Garcia’s 30-foot boat has four outboard engines, an excellent radar system with GPS and coastal maps, sonar, and a mount for a .50 caliber machine gun on the deck. The captain raced us out into the gulf where we found a line of banana freighters towing barges on a choppy afternoon sea. The lumbering freighters rose out of the water above us, rust-streaked leviathans.

- Carmen Palencia, a banana exporter, packs her products along with her husband. Palencia’s first husband was assassinated by paramilitaries in Cordoba state. She ran away with her children to Urabá. There she became a union organizer and fought for land she and others farmers squatted on for years. She was shot five times by paramilitaries but narrowly survived after being in a coma for weeks.

We drew alongside one of these vessels, the reefer ship Nelson Star, while Garcia called her skipper on his cell phone and said we were going to board with the German shepherd. The captain of the Nelson was not happy about it, although he agreed. Garcia’s Midnight Express pilot maneuvered his vessel with skill, but the seas were too rough and we were too low in the water to reach the descending gangway. It reminded me of two species unable to mate. The captain called off the attempt.

The crew of the Nelson had gathered by the railing to watch Garcia, all of them wearing the same grease-stained blue coveralls. They did not wave or make any gesture of greeting. If we could have yelled out questions over the water, they could have explained that they were carrying fruit in refrigerated holds like all the other freighters in the Gulf of Urabá. A longtime member of her crew might have also told us that the Nelson had not always been the Nelson, but had changed her name from the Chiquita Jean when, in 2003, Chiquita Brands sold her back to a Norwegian shipping company along with the rest of its entire fleet. In fact, from the moment of her birth in the Norwegian yards in 1992 until 2003, the ship was a Chiquita freighter, designed to keep the fruit in perfect condition on its long voyage over the oceans. The captain said, “Sometimes they put the drugs on the banana boats.” I was stunned. I had been under the impression that drug traffickers only used small fast boats to move cocaine from place to place, but this isn’t true. The freighters are difficult to search and blend into normal shipping traffic—because that is exactly what they are. They can also haul a ton at a time if the kilo bricks are well hidden.

* * * *

In the late eighties, the ancestor of the AUC began as an extreme right-wing confederation of armed bands—largely funded by cocaine trafficking—that fought the FARC across large regions of Colombia. Naturally, their political interests were allied with the Colombian government, which also wanted to destroy the FARC—but, unlike the army, the AUC could operate without restrictions. In the space of a few short years, the AUC would be responsible for the vast majority of political killings in the country, and the group’s leaders would boast that a significant percentage of the nation’s legislators were under their direct control. From 2000 to the end of 2002, there were at least 11,500 political killings in Colombia, most of which the AUC committed. It was a long-running human rights nightmare.

In 1997, shortly after the AUC arrived in Urabá, it began to consolidate power through a series of massacres and assassinations intended to drive out the FARC, which had organized in the banana fields. Swept up in the paramilitary net were civilians who had no connection to any armed groups. A large number of villagers and workers were summarily executed after being tortured or fingered as sympathetic to the FARC. Many of the killings took place around river towns. AUC gunmen would arrive, assemble the villagers in a central place and begin to interrogate them. Often, they were killed regardless of their answers. Establishing guilt in this system is just a pretext for widespread murder. It was a tremendous success. Eventually, the AUC controlled the entire banana-growing region of Urabá, any leftist agitators were in hiding, and the AUC had access to the Chiquita port. They controlled it, but the commanders were still engaged in a brutal fight for control of the banana and coca fields. They faced a serious logistics problem. The paramilitary group was winning, but it badly needed war material to expand its influence.

On November 5, 2001, four years after the AUC arrived in Urabá, a mysterious shipment of thousands of AK-47 assault rifles and millions of rounds of ammunition arrived at the Chiquita docks, a lethal cargo that went directly to the AUC commanders. Aside from an Organization of American States (OAS) report that focused on the two Israeli arms dealers who arranged the deal from Guatemala and Panama, there have been few details to emerge about how the weapons were handled on the Colombian side. It is also true that people directly associated with the shipment have had a tendency to disappear. The Mexican captain of the Otterloo, Jesús Iturrios Maciél, sailed with the ship on November 9 to Barranquilla and then vanished. The shipping company that owned the Otterloo closed its offices in Panama a few days after news of the weapons broke in a Colombian newspaper. The information in the OAS report suggests that someone formed the company just to deliver the weapons to the AUC.

In a front-page deal reached with the US government this year, Chiquita pleaded guilty to making millions of dollars in payments to a group on the State Department list of foreign terrorist organizations: the AUC. Lawyers for the company argued that they were forced into the making payments out of fear for the safety of its workers. Chiquita also admitted that they had a similar arrangement with the FARC. The result of the plea deal was a $25 million fine for a business that earned $3.9 billion in revenue in 2006, and there were no charges filed over the weapons shipment. It is not surprising that Chiquita Brands was forced to make protection payments to armed groups operating around their plantations, but that is not the entire story.

In March 2007, Chiquita told CNN that the weapons shipment and the protection payments to the paramilitaries were unrelated. This may well be true—the weapons shipments to the AUC were connected to a dark series of events at the company’s port. The Colombian government cast doubt on the company’s claims of being the victim of extortion by the AUC. Mario Iguarán, the Colombian attorney general, said, “It was a criminal relationship: money and arms for the bloody pacification of Urabá.”

- A Colombian Coast Guard officer on patrol in the gulf of Uraba. In the background is a banana freighter, the type of vessel that has been used by the AUC to smuggle drugs in the past.

* * * *

I first saw the AUC man sitting at the roof bar of the Almirante José Hotel, hunched over a beer. When a waiter walked close to him, the man looked him up and down, but the glance was sidelong and hooded. He looked nervous and didn’t want anyone walking up next to him. In the darkness on the roof of the hotel, he said nothing for long periods and then spoke rapidly, slamming his hands down on the table. He said he felt betrayed and abandoned by his former commanders. He was broke; demobilizing didn’t help him at all. Killings and vendettas followed him around, hovering over him wraithlike and invisible. I have noticed that all assassins have something in common, and it is present in the dead look the AUC man gives the waiter. The girl behind the bar went into the back room. She didn’t want to hear what he was talking about. It grew late.

I have changed the name of the AUC man to Lorenzo to protect him from being killed by members of the paramilitary group, his former comrades. It is something he thinks about all the time, how talking about this subject is dangerous. In the distance there were veins of lightning in a mass of black clouds as a storm came in. Lorenzo was still hunched over the counter as though nervous about people seeing his face. The girl had come back to bring us more beer. We were drinking Aguilas and the night was winding down and I was half-listening to the conversation. Everyone else had gone downstairs. Carlos turned to me and said, “Is there anything you want to ask him before he goes home?”

“I want to know if he heard anything about a shipment of guns that arrived at the Chiquita docks.” Years had passed, but it was worth a shot.

“Sure,” Lorenzo said, “I was there. I supervised the unloading of the rifles.”

Everyone fell silent. We listened to sporadic gunfire coming from a nearby neighborhood. Finally, Lorenzo started to tell us how the weapons arrived, how they were packed, and what he did that night, how he made sure his men put them on the trucks and that none were missing. They had been disassembled and carefully sealed in plastic bags for the trip over the sea, tucked away in farm supplies in the containers. As he talked, there was another burst of gunfire.

“Was there more than one shipment?” I asked him.

“Yes. I heard there were others, but they didn’t arrive at the Chiquita docks, they arrived somewhere else.”

Freddy Rendón, who commanded the Bananero Block of the AUC, confirmed this detail from prison in an interview with El Tiempo a few weeks after we talked to Lorenzo in Apartadó. The Urabá region is where the AUC received its weapons. It’s a perfect contraband port, which is why it was so prized. And there was not a single shipment but a series of them, and these deliveries occurred at the time when the AUC was taking new territory, killing with impunity, and making millions. The AUC had come up with a brilliant system to import weapons to Urabá after a great deal of thought and effort. Like the octopus, the paramilitary group adapted and thus solved a critical problem in its environment: its need to supply a growing army. After the rifles arrived at the Chiquita docks, there was an epidemic of AUC killings.

As we were leaving, I asked Lorenzo if we could tape an interview with him in the morning. He agreed on the condition that his face be hidden.

* * * *

The next morning, the three of us took the buseta back to Apartadó, not far from where the big weapons shipment arrived on the Chiquita docks. Seeing three men enter a dive hotel with a video camera, the maid tending the rooms thought a porno film was in the works. When we tried to explain, she laughed and turned down the beds. We had arrived in the middle of a driving rainstorm.

We set up the camera and adjusted the lighting to obscure Lorenzo’s face.

Lorenzo has the face and the dark skin of an indigenous South American. His habits are rural, and other Colombians think he is coarse and without manners. They are also afraid of him. Lorenzo is a spitter who leaves a constellation of saliva spatters on the floor. He can’t help it; he can’t stop the saliva from filling his mouth.

- A demobilized paramilitary fighter, “Lorenzo,” in Turbo. After turning in their arms, many AUC fighters have not found productive work and are under pressure to return to their former activities. Lorenzo described how paramilitary groups were reactivating in his area.

We started by discussing Lorenzo’s position in the AUC, his rise through the ranks. Lorenzo lifted his shirt to show the bullet scars on his chest and legs. He has at least six wounds on his body, including exit holes, some from combat with the FARC, the rest from a robbery attempt when he was traveling alone, carrying the supply money for his AUC brigade. Three of his own men robbed him, shot him and left him for dead in the city market. “I was so confident, I just went to the market alone with the money,” he told me. Lorenzo still keeps his revolver handy, in case he runs into one of them. Over time he rose to the level of commander in the AUC. “I worked with the Bananero Block. Those arms made it to many blocks. They divided it among I don’t know how many. The company gave a lot of support, and that armaments were divided among many blocks. And I realized that they were distributing it everywhere and that Mancuso’s people were getting the arms, too. So I found out about that and I noticed that. Different blocks shared it. Some of them would be M9s, Monterus, there were lots of AK-47s, there were M60s and PKMs. They were all brand-new and they went to different fronts.”

When the Otterloo arrived, Lorenzo worked from evening to dawn at the port loading the AUC trucks. It was a large shipment, fourteen container-loads of equipment, and it took a long time to move. “Another thing I noticed was the exchange of drugs for weapons,” he said. I caught this statement after I had the entire tape translated in Bogotá a few days later. What exactly was happening at the Chiquita docks?

When I saw the transcript of the interview, I decided to fly back to Turbo with Carlos and ask Lorenzo about the drugs-for-weapons exchange and the Chiquita freighters. I wanted to understand how the system worked.

* * * *

Everyone in the state of Antioquia awoke to the news that an image of Christ had appeared on the wings of a moth. Our friend, the former AUC killer, was an hour late for a meeting. Maybe he had lost his nerve. Maybe he was dead. In any case, there was nothing to do except wait on the roof and watch the Colombian newscasters compare portraits of Jesus to the markings on the televised insect. The tone was serious. No one on the television was joking about a potential miracle happening around the time of the Feast of the Virgin of Carmen. Carlos swore there was no resemblance, but he just didn’t want to admit it. There was a resemblance, although it could also have been Mary trapped in the moth wings, covered in a dark hejab, or an Iraqi girl framed by dun-colored sand.

On the roof of the Almirante José Hotel, the air was warm and thick. Across the Gulf of Urabá to the west, we could see the hills of the Darién Gap, which leads to the border of Panama. Above us, the sky was another sea. Tropical storms born in the Atlantic were growing in strength as they made for the Caribbean coast of Colombia, where they would flood the streets and the fields. It was impossible to sit still and simply wait, but there was nothing we could do. It was hard to know whether to be worried or not. “Man, I really think that he’s not going to show. We scared him off,” Carlos said when we were sitting at the table. The killer had always been friendly to us, but at this moment, he was down on his luck and paranoid; he could have changed his mind. In the past, when we called him, he arrived within minutes.

Lorenzo has come to trust me. All of this has taken some time to work out, over long nights of drinking. I asked questions only when he seemed relaxed enough to answer them, and even then he was often careful not to say the names of the men he worked for.

He grew up poor in a mountain village and joined a left-wing revolutionary militia called the Popular Liberation Army (ELP) when he was eight, after they promised to pay him a salary. Of course, what really happened was that he was taken as a child soldier by a group that would eventually be defeated by an up-and-coming right-wing organization. After growing up in the jungle and learning how to fight, Lorenzo ran away from the ELP when he was fifteen and then joined AUC in the mid-nineties. For assassins at the time, it was like Silicon Valley during the great boom.

Lorenzo worked first as a soldier and later commanded 600 men in the Medio Atrato river zone, where he fought against the FARC. Lorenzo then worked for El Aleman—“the German”—the commander of the Bananero Block, whose real name is Freddy Rendón. From 1997 until its dissolution in 2003, the Bananero Block of the AUC controlled the territory where the Chiquita Brands subsidiary, Banadex, had its vast banana and plantain operations.

During his time with them, the AUC, under the leadership of Salvatore Mancuso and the Castaño brothers (Carlos and Fidel), committed some of the worst atrocities in the Americas. And despite a well-publicized government amnesty program, the AUC still exists in a clandestine way. Before turning in his rifle last year, Lorenzo was responsible for his own share of killings, a number of them in cold blood. Over the course of our two weeks in Urabá, it became clear that he had learned a great deal from his time working for the Bananero Block of the AUC. Lorenzo is a living archive of paramilitary data, and his commanders, the duros, the hard men at the top, trusted him with some of the most sensitive tasks.

- A masked paramilitary soldier from the Metro Bloc guards his commanders at a meeting in Antioquia in September 2003.

Just as we were about to give up, Lorenzo appeared, smiling as if nothing was wrong. We found a table in the corner and I asked him about the drugs-for-weapons exchange and the Chiquita freighters. “Look, for every kilo of drugs they put in, they had to pay 500,000 pesos. If you’re a drug trafficker, and I’m in control, you’d have to pay me. You have 20 kilos of coca, or you have some other cargo, and I own that region—you understand me? You pay me 500,000 pesos for me to ship those drugs as if they were mine, in the boats. You understand? Chiquita’s boats. That’s what the Bananero Block had going on here.” Lorenzo watched the AUC load drugs onto Chiquita boats; he knew about it because he was there when it happened. “Look, there were drugs, and there were times that they sent drugs for weapons. They sent the kilos of drugs, and from out there, those duros said we are going to send this many kilos of drugs and I need this many rifles,” Lorenzo said.

What Lorenzo described was a successful scheme that allowed the AUC to act as a contraband-freight consolidator. The AUC could ship their own cocaine on the company freighters or they could ship product belonging to someone else for a tax of roughly $250 per kilo, which works out to a quarter of the Colombian value of the brick. And the smuggling scheme was a direct side effect of gaining access to the port. Lorenzo insisted more than once that Chiquita employees knew about the cocaine: everyone in the chain was paid a percentage to keep quiet, including the freighter captains. To place a metric ton of someone else’s product on a ship they did not own, the AUC would have made $500,000, not a bad haul for taking no real risk. And the paramilitaries received the money whether the product was intercepted or not. When they shipped their own cocaine, the AUC took the same risks as everyone else. Hiding cocaine in regular freighter traffic makes it hard to find. The freighters are enormous vessels.

Without access to the Chiquita port, the AUC couldn’t have exported drugs and bought weapons so easily and could not have grown quite so fast as it did in the late nineties. It was a key part of their metabolism during that time—if you make money from exports, you need to get them to market so you can further expand the business. Chiquita, after a hundred years in the banana trade, understood this very well. For the paramilitaries, using the port was a straightforward decision based on necessity. Lorenzo believed that the AUC must have shipped tons of cocaine using this system, because it went on for years.

But did Chiquita know how its ports were being used? We asked him that question many times and his answers did not vary: “From Chiquita there had been people who knew that they were shipping drugs. Employees. People trusted by them,” he said. He was adamant: Chiquita employees knew about the drugs as well as the weapons.

On our last night in Turbo we went to drink a farewell beer at a place on the main drag. Lorenzo was nervous because he was not in his own neighborhood, but he was too polite to say that we picked a bad spot. In the neighborhood around his house, there are men endlessly riding around on bikes who watch out for him, let him know what’s going on. We saw those men ride by, checking up on him. They all had the close-cropped haircuts of paramilitaries but wore civilian clothes. Lorenzo leaned close to tell me that, given some time, he could find other AUC soldiers who could talk to us about the weapons and drugs, that he had some names, but that he had to be careful because some of these men were still active. Before long, the rains arrived with such force that the streets became riverbeds, torrents of mud-colored water coursing down them. Kids rode their bikes through the deluge, sending rooster-tails of water into the lightning-charged air.

- Salvatore Mancuso talking to AUC troops of the Catatumbo block on December 10, 2004, the day of his demobilization in Tibu, Colombia. The Catatumbo block was blamed for more than 5,000 deaths before it disbanded.

* * * *

There are beggars and a mentally retarded boy who hang around the gates of the maximum-security prison at Itagüí looking for tips. One old woman offers to clean the fingerprint ink from your hands when you leave in exchange for a few coins. It is a good business because everyone has ink-stained hands if they leave through the gates. This was the most important aspect of the security at Itagüí, the pressing of blackened digits into ledgers. The guards were relaxed and so were the senior officials and the secretaries in their clean blue uniforms with their American-style Velcro patches. Everyone was having a normal day in a beautiful town in the Andes behind a high fence. Above us the mountains intercepted the clouds.

The guards waved me through the checkpoints in a friendly and reassuring way. A few minutes later, I was waiting in an office in the administration building for Salvatore Mancuso, leader of the AUC, to appear—but he didn’t appear. Out in the hall an official from the Colombian prosecutor’s office was also waiting to talk to Mancuso, but the official wouldn’t come into the room. The young prosecutor walked in slow circles in the dark hallway, waved once, and then went back into the gloom.

A senior prison official came in after an hour and apologized for the delay. “I am sorry. Mr. Mancuso is getting a massage from a girl, and he has to shower and get dressed. He will come and talk to you when he is ready,” he explained.

“His life here is very slow,” I said. Mancuso was going to make us all wait so we would know who was in charge.

“It certainly is. Patience is very important,” the officer said and smiled sadly. We waited in the office a long time, long enough to notice how the light changed on the mountains. The prosecutor who was waiting outside finally couldn’t take it anymore and came into the office with me. He sat at a nearby desk. The prosecutor held some information about me in a portfolio that he wanted to verify. I could hear the leader’s voice coming up the stairs before he came through the door. Mancuso has a great voice, a deep baritone that could have come from the opera house. The boss brought two of his friends with him. One of them, an older professorial man named Juan Rubbini, edits his website and writes about the AUC political program. The boss towered over them all. Salvatore Mancuso, the former English student at the University of Pittsburgh who became the leader of the AUC following the death of Carlos Castaño, was now ready for his audience. In the past, he has implicated officials as high as the Colombian vice president in connection with paramilitary groups, and he is still a powerful man.

We all shook hands, and then Mancuso disappeared with the official from the prosecutor’s office and promised to return soon. Under the Justicia y Paz law, Mancuso is supposed to confess the details of crimes he committed while he ran the AUC. In exchange, he is allowed to serve a comfortable eight-year sentence in Colombia. The government has not taken his money or forced him to reveal the exact extent of his criminal organization.

Mancuso’s comforts in prison abound. The former head of the AUC has internet access, a phone, and regular visits from friends and family. In fact, he has the run of the place and walks around without an armed escort. The guards call him by his first name. In May, La Semana, an investigative weekly in Colombia, published a report based on telephone and e‑mail intercepts of paramilitary members in Cellblock 1, where Mancuso lives. In the intercepted calls, men close to AUC leaders instructed men on the outside to continue extortion schemes and commit murder. One man close to Mancuso called El Flaco was recorded as he handled orders for the purchase and sale of cocaine. It would appear from these conversations that the AUC, all cooped up in a single cellblock in Itagüí, did not give up all its power. AUC duros on the outside still wait for orders.

Rubbini, Mancuso’s friend, turned to me while I waited for Mancuso to return and said, “This man demobilized 30,000 men, and they put him in a prison!” I said I thought it was remarkable. Rubbini clearly loves Mancuso and admires him and spends serious time writing down his political views. Finally the boss returned and I had to ask the other two men to leave.

Mancuso was nervous at first. It might be that he doesn’t often speak to Americans or that he doesn’t trust the press. When I took out my recorder, Mancuso produced his own digital voice recorder and asked if it would bother me if he used it. I said, no problem at all.

I started by asking him about his political ideas. It was the FARC that started the whole business with coca, he told me, and that’s how the AUC got interested in it.

Finally, when he seemed completely at ease, I asked Mancuso about Chiquita and the shipment of weapons that arrived at the Chiquita docks on the Otterloo in November 2001. Mancuso’s demeanor instantly changed as he listened to the question. It was an intense moment, watching him respond to an unexpected development, calculating his odds, weighing his answer more carefully. He began by appealing for an appreciation of the broader milieu.

“What must also be clearly understood is the historical context that existed at that time. What were the pressures [Chiquita] faced, what was happening with them in that area. The part of Urabá where they had their banana investments was completely dominated by the guerrillas. The Colombian state was precarious there. They had to do what the guerrillas told them. In fact, they were thinking of selling their property and leaving the country at that time. When we entered the area and confronted the guerrilla phenomenon, we told [Chiquita], ‘Look, you are the best generators of jobs, of labor, of stability in the area. Stay here, don’t leave, keep investing. We’ll provide you with protection, but in exchange for that we want you to pay a tax.’” On the central question of drug exports from the Banadex port, Mancuso said in his clear, educated Spanish, “In the specific case of Chiquita, I don’t know. But surely they must have loaded up a lot of ships there. Now, I don’t know if Chiquita had its own fleet or not. I think that they didn’t have one, that the ships that came in were from the shipping line, and surely those boats were used and loaded with drugs.”

In fact, from the time of the weapons shipment until 2003, Chiquita maintained its own fleet of ships, which regularly used port facilities in Urabá, the site controlled by the AUC. These are the boats that Lorenzo trusted men to load with the cocaine. Mancuso tried more than once to say that it was the drug traffickers who managed the smuggling, not the AUC, but this is hard to believe for a number of reasons, not the least being Mancuso’s own description of his organization’s involvement in the trade. His evasiveness is understandable; he is under an extradition threat and does not want to admit to more direct knowledge of drug smuggling than he has to.

I asked him if the AUC ever traded cocaine for weapons. Mancuso leaned over the desk and said, “Phillip, we did it many times. We exchanged drugs for guns. Basically, almost all the arms transactions were made either in drugs or [US] dollars.” He confirmed that this was a main part of their growth strategy, and then spoke about AUC export taxes for cocaine in Urabá. “They charged $500,000 per kilo? Look, there were blocks up there that charged a $100, $150, $200, $300 tax to dispatch a boat, or whatever was going out—a boat, a ship, whatever. It was the AUC block that charged.”

If I wanted to know the exact details, Mancuso said, I would have to talk to the commanders of the Bananero Block of the AUC, his subordinates. Lorenzo also insisted that Chiquita people had meetings with AUC duros about drug smuggling and weapons. Lorenzo knew the exact place where they had meetings, but Mancuso wouldn’t admit to knowing about a specific agreement to export drugs from the port, although he would go on to describe the AUC drug-export scenario in vivid detail. Mancuso said he did not believe that executives of the company knew about the drugs-for-weapons exchange, because it wasn’t necessary for them to know. “The people who run the port at an operational level had to be involved; those are the people who would notice all this.”

“How hard is it to exchange cocaine for weapons?” I asked.

“It’s the easiest thing in the world,” he said and smiled.

- Chiquita relies heavily on bananas grown in the Urabá region. During the 1980s and ’90s, Communist rebels of the FARC and members of the AUC fought bitterly for control of this region.

* * * *

The company will no doubt say that if there were any drugs shipped on its freighters when the AUC controlled its port, it did not know about them. But over the years, people did find out about it and were either intimidated or paid to stay silent. This export scheme was the exact mechanism that allowed the AUC to grow and to commit crimes on a vast scale. To acquire weapons it had to ship cocaine to the United States and Europe, so it looked for an export channel. Simple. In Urabá, AUC was merely a symbiont on the body of a larger corporation that happened to share its interests. It, too, was a kind of corporation. They fed off each other.

Outside the gate of the prison, the old woman asked me how it went. I said that it went well while she cleaned the ink from my fingers with a spray bottle. The air had warmed up since the morning. The same police officer smiled and waved, and I started walking down the hill to town. Below the mountains of Itagüí, people were getting ready for the Festival of Flowers, while above them drifted the legions of Colombian ghosts who follow their every move.

Phillip Robertson and Carlos Villalon traveled to Colombia on a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting. More about this project on the Center’s website.