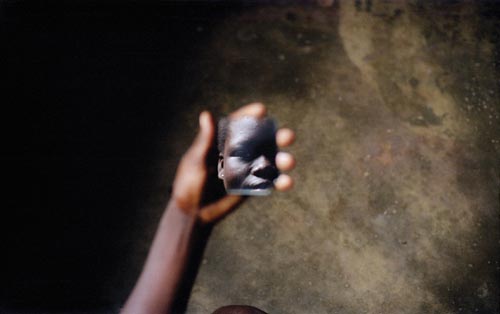

In her bedroom, Selassie examines her reflection in tiny broken mirror. She lives in a traditional Troxovi shrine of the Ewe people in Ghana. When she was a small girl, her family brought her to the shrine to make amends with a god who was angry because of a crime committed by her ancestors, years before Selassie was born. She is a fiashidi, defined in the Ewe language as a “queen fit for a king” and a “wife of the god.”

There are thousands of women like Selassie, young and old, who serve in the shrines to atone for the past crimes of their family and society. This age-old practice has sparked controversy nationally and internationally. Those calling for abolition of the practice call Selassie a trokosi or “a slave of the shrine.” The women lack freedoms, they say, are forced into physical labor and sexual relations with the priests. And so they have made it their mission to eradicate this practice and to “liberate and rehabilitate” the women and girls through vocational training and Christian counsel.

I traveled to the town of Klikor in southeast Ghana, home to Selassie and hundreds of other fiashidi, seeking answers: What does it mean to be a wife of the god? Is Selassie a queen of the town or a slave of the shrine?

God is worshipped throughout Ghana in a variety of ways. He is heard, seen, and referenced in the beat of the drums, movements of the dancers, marks on the body, patterns on cloth, trees growing in the sacred forest, and inscriptions on the rear of taxis. The majority of Ghanaians are nominally Christians or Muslims, but they still hold traditional beliefs. When Christianity arrived in the Gold Coast in the mid 1800s, the Ewe people were depicted as wild barbarians and Satan-worshipping pagans. The Christian missionaries preached their belief that conversion to Christianity equaled conversion to modern life. Yet while technological modernity and progressive thought are accepted in Klikor (some townspeople have cell phones), the older religious beliefs are still strongly held.

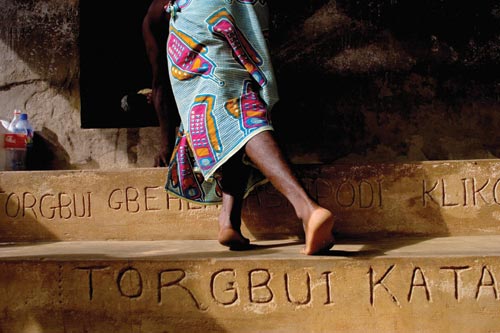

The Ewe people live in coastal areas in southeastern Ghana and the southern areas of Togo and Benin. Their ancient religion is rooted in the powers of the earth and its supernatural forces. They believe in God, the Supreme Being, and often refer to God as a spouse. The Ewe also believe in spirits or smaller gods, who do the will of God and have shrines devoted to their worship. Tro, a war god, is one of those deities. Hundreds of Troxovi shrines exist throughout the region, each hosting an uncountable number of fiashidi who call the god, Tro, their husband. In Klikor, a town of around 8,000 people near the border of Togo, the Troxovi shrine is the most powerful religious institution in the community.

My feet burrow into the soft and smoothly swept sand at the entrance to one of the three main Troxovi shrines in town. The sweet smell of apeteshie, the local drink made from sugar cane and palm, lingers in the hot still afternoon air that sticks to my bare shoulders. I am wearing only a cloth tied beneath my arms, following the regulations for all who enter the shine. Light filters in through gaps in the tin and thatched roof, illuminating benches crowded with older men, middle-age women, and new mothers with infants wrapped to their backs. They are waiting their turn for prayer or have come to pass the time gossiping. Goats and chickens tied with twine to benches wait to be offered as sacrifices to the god.

Torgbui, the priest, is dressed in the traditional attire of a Troxovi priest—a cloth around his waist, a straw necklace and cap for spiritual protection, his wrists and ankles piled high with cowry shells to signify spiritual wealth. People take turns bowing before him. On their hands and knees, they quietly tell their worries to the priest to pass onto the god. They pray for a successful business, a good harvest, the health of a sick child, the resolution of quarrels and crimes.

Two fiashidis sit beside Torgbui. The blue cloth around their waist signifies their status; a smaller straw necklace is tied around their neck for spiritual protection; their wrists are lined with colorful beads, and their toenails gleam with fresh paint. The women pour the apeteshie into tiny coconut shells. Calling to the ancestors, Torgbui pours the drink on the floor and prays. He then hands out money to the worshippers.

I watch as twenty-six-year-old Mama nervously sits at the shrine for her initiation to become a fiashidi. Years ago her family began suffering many misfortunes—deaths, illnesses, failing business. They sought consultation with the god through a diviner and found out that long ago, an ancestor committed a crime, and the misfortunes would continue unless a female—he specifically named Mama—came to the shrine to marry the god. Mama goes through with her initiation rites: prayer, consulting a diviner, and going to the sacred forest for ritual blessings. The next day Mama is more relaxed having realized that nothing scary or harmful has happened. She, however, does not want to start a new life and live at the shrine. At home in Togo she is finishing up hairdressing school and has a boyfriend. Despite pressure from her family, the priest and the god, and years of tradition, a few days later Mama leaves the village to go back home.

The fiashidi are under no physical obligation to the shrine or priest. Many remain in the town, establishing their own households and businesses and receiving economic support from both their family and the priest. They lead people to prayer and help around the shrine. As fiashidi, they are protected from being cheated, cursed, or robbed. They are among the most economically and socially privileged women, and are treated as “Queen of the Town.”

-

- A fiashidi pauses to say a silent prayer while sweeping the floor in between the male and female Troxovi shrines in the sacred forest in Klikor.

-

- Torgbui Adzima, a priest of one of the three Troxovi shrines in Klikor, prepares for an afternoon walk through town. The priest must always dress in a blue robe, carry a staff and wear an eshie, a straw necklace, around his neck to symbolize his spiritual power.

-

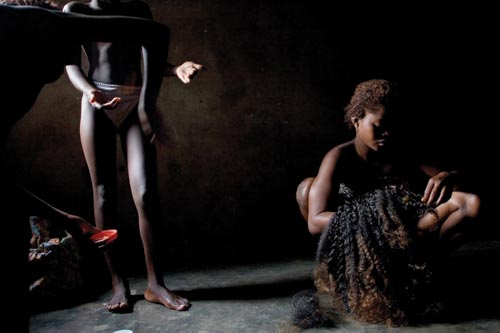

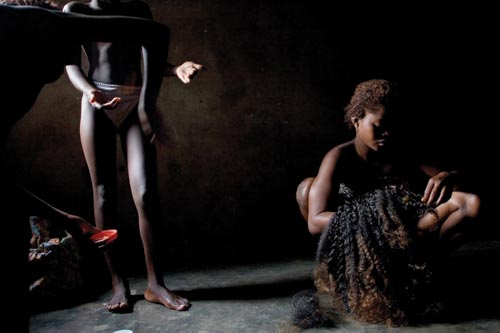

- Inside their bedroom in the shrine, young fiashidis start their day by applying lotion and brushing hair extensions. For some of them, living at the shrine is a vast improvement over the impoverished homes from which they came. A fiashidi can be any age and is replaced by a family member when she dies.

-

- Fiashidis fight for a chance to fill their calabashes with mud to plaster the walls of the shrine, a job done only by the women. Plastering the walls happens once a year during the Troxovi festival and it offers the women a chance to pray directly to the god. Those trying to end the practice of taking fiashidis say the women are slaves forced to plaster the walls as a punishment and form of physical labor.

-

- Adzo Ashipodi dresses in her finest cloth and beads to dance for the priest during the festival of the drum.

-

- Mama, 26, sits at the Troxovi shrine during her initiation as a fiashidi. Her family bows to the priest and presents the required gifts which they have spent years saving for Mama to have. Despite pressure from her family, Mama decides not to live in the shrine and returns home to Togo. The priest and families take care of the fiashidis financially. In return, the fiashidis help lead people to prayer and assist the priest. Opponents of the practice claim that the women are coerced into sex with the priest and forced to stay at the shrine against their will.