One day in 1962, a man in Chile woke up blind. The cause was a pituitary adenoma: a tumor, benign but expanding, that had encroached on and finally compressed his optic chiasma. Adolfo Carmona—husband to Raquel, father to Queli, Bebo, and Gemi—could no longer see. We all owe our lives to someone’s vision and someone else’s blind spot, but it’s seldom quite so literal: I owe my existence to that tumor and the sight lines that developed around it.

One day in 1962, a man in Chile woke up blind. The cause was a pituitary adenoma: a tumor, benign but expanding, that had encroached on and finally compressed his optic chiasma. Adolfo Carmona—husband to Raquel, father to Queli, Bebo, and Gemi—could no longer see. We all owe our lives to someone’s vision and someone else’s blind spot, but it’s seldom quite so literal: I owe my existence to that tumor and the sight lines that developed around it.

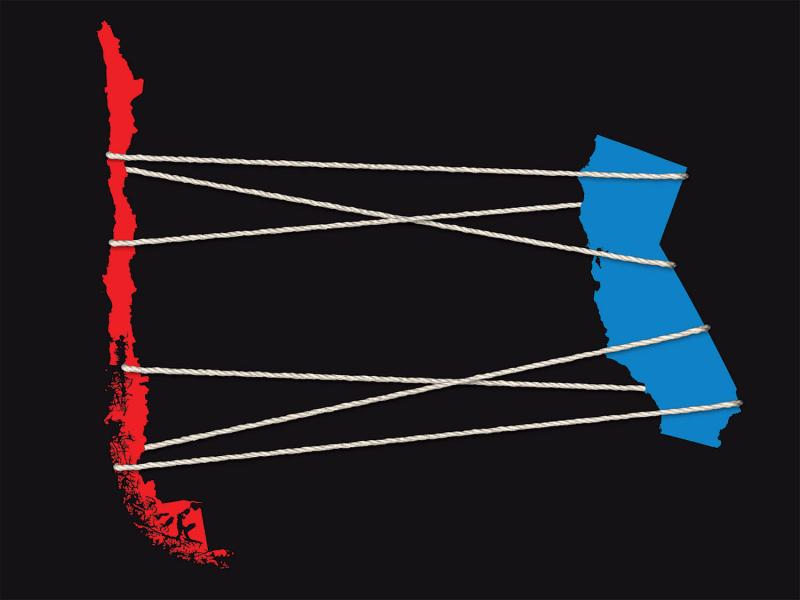

JFK had a vision. The Chile–California Program was part of his Alliance for Progress, an initiative partnering with Latin American nations to deliver them from the third world and its Communist temptations. The Chile–California Program proposed that the state of California do something no other state had done with a foreign nation: formalize a “special” relationship with Chile, both in recognition of their shared geographical features and because both fostered a kind of homegrown technical creativity, a gift for engineering raw materials into a kind of commercial sublime.

California and Chile both style themselves the fruit baskets of the Americas. Fruit, not bread; luxury, not necessity. These days, both are efficient, abundant, and slightly high-end producers of almonds and avocados and wine (rather than, say, corn). That California was a state and Chile a country seemed like exactly the kind of unimportant technicality Alliances for Progress were supposed to overcome. But in fact, this model for economic and intellectual exchange between an American state and a foreign country was unprecedented. And this essay is, in its way, the history of how that geopolitical mismatch between a giant state and a tiny nation filtered through actual people, down to me.

The program launched in December 1963 with an office in Santiago, Chile, a backup office in Sacramento, California, and the kind of vague promissory language that sounds like an excuse for a party. The director in Santiago was ostensibly in charge of policy; the deputy director in Sacramento was supposed to drum up interest from the private sector via bureaucratic undertakings like VIP visits and sister-city programs.

Fifty years later, what this iteration of the program achieved was quixotic but concrete. It transported three used fire trucks to Chile, shipped enameled cherry cans to Santiago, and coordinated and funded visits by several American engineers, urban planners, and agricultural experts.

It was also—informally, but definitively—the vector through which my family came from Chile to California.

In the years before Adolfo’s tumor blinded him, the Carmonas performed the comfortable normalcy of a typical Chilean middle-class family. Adolfo was an engineer, Raquel (née Gonzalez) was a schoolteacher. Angular and elegant with an aquiline nose, she stayed home to raise their three children, Raquel (nicknamed Queli), Adolfo (Bebo), and Cecilia (Gemi). Raquel cooked and sewed and managed her fractious husband, whose mounting paranoias would eventually be explained by the adenoma whose growth no one yet suspected.

Theirs was not a love story. Raquel (Quela to her family) craved conventionality with near-radical fervor. When my grandmother Liliana, Quela’s sister, annulled her own unhappy marriage, Raquel soldered the rifts in her own. Liliana tended toward a diffuse policy of parental laissez-faire—she worked full time arbitrating disputes between farm workers and their “patrones”—but Raquel was a detail-oriented homemaker, an engineer of perfection. She kept up the appearance of her marriage long after her husband lost his ability to appreciate the illusion.

Like most illusions, Quela’s force field was as hermetic as it was attractive. As the architect of her family, her approach was a loving geodesic dome: structured, but risk-averse, clannish, and closed. No one could have guessed from their perfect portraits that in a few short years they would be forced to scatter. The girls would go to a nunnery in Florida to learn English, Bebo would stay in Santiago to care for his blind father, and Quela, a woman in her forties who’d make Martha Stewart look slapdash, struck out for California, alone and penniless, as so many Chileans had done before her.

Chileans have always been spry fortune-seekers. They’re sometimes called 48ers instead of 49ers; their arrival at the California gold rush was that quick, their mining knowledge that extensive. They were some of the only experienced miners in California in those days, and frequently taught “gringo” newcomers how to dig shafts and pan for gold. One of the most common, if simplistic, ore-crushing tools in the California gold fields was the Mexican arrastre;Chilean miners brought with them the more sophisticated two-wheeled apparatus still known as the “Chilean mill.” And Chile fed California: The newspapers were peppered with daily ads for Chilean barley and flour, which were generally cheaper than America’s own. The flow of commerce and technical knowledge has gone in both directions: If the United States has tended to see Chile as yet another “developing” nation, California and Chile have a long, mutually beneficial history.

Chilean capitalists were—then as now—gifted at spotting and exploiting opportunities. Many found that setting up shops in San Francisco was more profitable than searching for gold. Some of the richer Chileans who came to California brought their peones with them—dependent workers who claimed sites in their own names but worked them for their patrón (often for very little pay). That didn’t sit well with some American prospectors, nor did the fact that foreigners had claimed some of the best sites.

In December 1849, a group of Iowans decided to target and expel foreigners from sites they wanted to work. Intimidation tactics worked in some cases, but Chilean miners proved generally hard to intimidate. The Iowans claimed that the Chilean “peons” were slaves in a free state, and got a Judge Collier to issue an eviction order: The Chileans had eight days to vacate the site or be forcibly evicted. The Chilenos coolly informed the Iowans that they had never voted for Judge Collier and therefore didn’t recognize his authority. And what started out as a conflict in the mines of the Wild West devolved (or escalated) into a battle over paperwork: Finding a judge of their own, the Chileans asked him to issue a warrant for the Americans’ arrest, petitioned for authorization to personally make the arrests, and obtained it. They invaded the American camp, and managed to legally take more than a dozen extremely surprised Americans prisoner.

(The story ends badly for the Chileans: The Americans freed themselves, captured their captors, “tried” the Chileans, and executed three. Still, the so-called “Chilean War of Calaveras County” established the “Chilenos” as a force to be reckoned with in the courts as well as on the battlefield.)

I can’t read about these Chilean invocations of legal process without thinking of my mother, who still lives in California gold country and—though she has no formal legal training—routinely triumphs in the courts. Legalese is in her blood, as is procedural escalation. She often brings a gun to a knife fight, rattling off labor codes, filing liens, demanding sanctions. Misbehaving lawyers slink back to their employers, forced to explain that a routine refusal to pay an uppity interpreter somehow escalated into a trial that—against all odds—they lost.

No one knows how large a presence the Chilenos actually were in California, because they preferred a joke to the truth. Of the many places in California where traces of Chilenos remain—Chili Gulch, Mokelumne Hill, Placerville, Jackson (formerly Botellas)—Chilecito in San Francisco was the biggest. A kind of “Chiletown” located at the bottom of Telegraph Hill, Chilecito contained between 3,000 and 12,000 Chileans. It is impossible to nail down further; the polling was flawed, and those Chileans who were polled enjoyed themselves at the census taker’s expense. Official California census records solemnly report the presence of Juan Embromado (John Jokebutt) and Papa Masticada (Chewed Potato). One man listed his profession as “cuidaputas” (whoreguard). Another identifies himself as George Johnson of El Pico (Place of Origin: The Penis).

That sense of humor is also transhistorical. There is a family photograph of Quela with her older sister in California in 1974, posing with pearls and handbags in front of a sign that reads “Pico Way”—“Penis Way” to Chilean eyes.

Born in Chile to a Chilean mother, Quela spent her childhood in Cuba. Her father was a rustic Spaniard who made his fortune growing sugarcane. Theirs was a rudimentary but comfortable existence—the children were instructed by their mother in a sprawling two-story house surrounded by mango and palm trees.

This bucolic lifestyle was interrupted by an uprising against then-President Gerardo Machado. Revolutionaries took up residence at the hacienda, turned the salon into their headquarters, took the horses, and killed the animals. Quela’s mother—an intellectual at a time when few Chilean women were—fled to Chile with her seven children, leaving her husband to manage the sugarcane and the increasingly unstable situation.

For the family, this was a disaster, but Quela’s reflections were typically upbeat, tidy, and detached. “In spite of everything the trip was fun,” she wrote of the sea voyage home. “We forgot our problems and the revolution.”

The Gonzalez family adapted to life back in Chile, helped by the money that still flowed in from Cuba, until one day it stopped. Quela’s father lost everything under Fidel Castro. Even worse, Quela’s brother—who’d gone back to Cuba to assist his father—was in jail. He spent seventeen years as a political prisoner. He returned to Chile a bitter and broken man and wrote a book, Azúcar Amarga, about his experience. He smoked, played chess, and penned angry editorials against the Marxist menace. He spoke of prison often, of the hatred he felt when a guard spooned a scoop of scrambled eggs into his bare hands. He despaired. When he died, his sisters discovered he’d been sleeping on newspapers instead of sheets, but because of indolence, not poverty.

Quela and her sisters were shaped by these extremes—the entrepreneurial wealth their father’s sugarcane experiments made possible (which contained its own form of patrician austerity, as they were never “rich”), punctuated by phases of disruption and loss. Their middle-classness was ruggedly aspirational. The Gonzalez craving for stability was structured by a lifetime of volatility and—in the women, at least—resilience.

Unsurprisingly, Quela made it a point to marry well: Adolfo Carmona was an engineer from a “good” family, and they set up house in Ñuñoa, a middle-class neighborhood in Santiago. They lived on the same block on Ortúzar Street as a young military man named Augusto Pinochet and his family. The children sometimes played together, but Quela and Lucía Pinochet didn’t particularly get along. As Quela raised her children and dealt with her husband’s increasingly difficult moods, Augusto Pinochet was rising in the military.

Then, on that morning in 1962, the illusion of stability was shattered. Adolfo woke up blind, and everything changed, yet again.

The Chilean War of Calaveras County in the mines in 1849 had its urban counterpart in San Francisco, where Chileans were also doing a little too well. Chilecito was attacked on July 15, 1849, by a gang of xenophobes calling themselves the “Regulators” or “Hounds.” They played a fife and drum, marched down Montgomery Street, and yelled “kill the Chilenos” as they tore down tents, beat the foreigners, shot two boys, and stole thousands of dollars in gold, jewels, and cash.

The Hounds were tried and convicted, but as I perused the trial transcript, the testimony that interested me most was from the mother of the two boys the Hounds shot. “I am the wife of Domingo Alegría,” she says,

and am the mother of the two wounded men. I was not at home on Sunday night. When I returned next morning, I found the tent torn down. Went to different tents to find my property. Saw one of the last night’s party who took away from my daughter some handkerchiefs she had got together, but prevailed on him to give them back. I then went to Domingo Cruz’s tent. The front was fastened. I went in at the back and found articles belonging to me. I commenced taking them away. Several men exclaimed they were theirs. They let me have a few things.

It’s a matter-of-fact account, notable for its understatement. In a time when the few women in California were in constant danger of being raped or worse, her response was to visit the responsible parties and calmly but firmly retrieve her property. This will be eerily familiar to anyone who has known a Chilean woman—especially one who immigrated to California.

When Quela died, her nightstand contained mementos, drawings from children, and a neatly written record of all those who’d borrowed money from her, and how much.

When the tumor arrived, the money departed, and Chilean medicine proved inadequate. Unless Quela wanted to do the unthinkable—abandon her husband, or watch him and her dream of living a conventional life die—she had to do the impossible: get him to the United States.

There was no money. So Quela did something that still astonishes me, even fifty years later, something all the more remarkable in Chile, where people avoid social embarrassment so energetically they’re practically British. Quela walked to the home of an ex-president, Jorge Alessandri, knocked on his door, introduced herself, and explained (proudly, cogently, trying hard not to seem like a supplicant) that she needed a way to use her teaching credential to get to California in order to cure her husband.

What’s astonishing is the act, not the outcome. No one collared by Quela—or Liliana, or, indeed, my mother—could resist her for long, and Alessandri was no exception: He arranged for Quela to meet with the minister of education under then-President Eduardo Frei. She left with a comisión de servicio in hand—a commission to teach public health for one year in California while continuing to receive her salary as a teacher in Chile.

Like the man who traded a paper clip for a house, Quela leveraged that tiny victory into more, sniffing out opportunity and acting with extraordinary speed. One day, she happened to step into the elevator at the same time as a Mr. Patrick DeYoung, the deputy director of the Chile–California Program, who was then visiting Santiago. I now know—having read all his correspondence—that DeYoung was a warm, ethical, hardworking man who’d taken a leave of absence from Lockheed to work as the CCP deputy director in Sacramento. Quela knew none of this. But such was the force of her personality that, by the time they’d parted ways, she’d determined how he could help her, and persuaded him to do so: Patrick DeYoung had offered to host her in his own home, with his wife and children.

But not her daughters. Or her son. Or her husband. She would have to mine for gold alone.

Before the US annexed Texas and California from Mexico, Chile was the most powerful maritime nation on the Pacific coast, a brief spate of supremacy that fueled centuries of grandiosity. Chilean arrogance is impervious to the smallness of its stature, and Chile has a long history of charming (and irking) its gigantic northern ally, through insouciance that Americans sometimes mistake for disrespect.

Take the case of Benjamín Vicuña Mackenna, a Chilean journalist, politician, and special Chilean envoy to the United States government who traveled to New York in 1866 to publicize Chile’s case against Spain. Spain was blockading Chile’s ports, and he hoped to secure some ships and torpedoes for the coming war. Mackenna’s letters home describe his experience in the United States with a typically Chilean combination of self-aggrandizement and self-mockery. When the Travellers Club invited him to speak, for instance, Mackenna sent them some books and materials in advance of his talk. On the day of the lecture, he noticed the books sitting on a table. The club president—who’d wholly misunderstood their importance—introduced Mackenna as an ambassador (which he wasn’t), a senator (which he wasn’t), and “one of the most distinguished and fertile authors of South America, as demonstrated by this stack of books that he has written and generously donated to this club.” “What to do?” Mackenna wrote home to Chile, narrating this incident. “How to contradict that barbarity without committing a greater one? I resigned myself, then, to passing as an ambassador, senator, and the most extraordinary writer that’s ever been seen since the formation of the world.”

When news of Mackenna’s letters to Chile got back to New York, his apparent lack of awe at the wonders of the United States enraged the American public. The New York Herald translated and republished some of the Chilean upstart’s letters and condemned him for receiving “all our kindness and then going home and abusing our country, its people, and its manners and customs.”

Yet Mackenna’s rueful description of his life in New York as a so-called ambassador is a riff on the gap between his fictional titles and his actual circumstances. “Figure to yourself this great Ambassador living in a single apartment,” he writes, “wherein is his bed, his washstand, his writing cabinet, and receiving therein all the Generals, Admirals, and colleagues that choose to honor him with their visits. Bear in mind that the great man has neither cook nor majordomo, nor lackeys, nor, indeed, (as he would have in Chile) has he a little shaver to brush his coat or black his boots.” The Herald took these observations hard: “Mr. Mackenna, and his secretary, Cueto, were impressed with the idea that, of all the countries in the world, Chile was the greatest, and, of the people of that Republic, they were two of the most remarkable. As to the latter point, they were about right, if we are to judge by their conduct.”

One hundred years after Mackenna’s jokes about the titles conferred on him by American ignorance, Ronald Reagan was elected governor of California. Privatization was a significant part of his platform, and so was slashing government programs.

It’s interesting to watch an institution fight for its life. The correspondence from DeYoung’s office remained efficient and calm during this period, but the volume increased. DeYoung started campaigning hard. I have no idea whether Quela got caught up in the nets DeYoung cast while in Santiago as he tried to build the case for the program’s existence, but she arrived at a moment of institutional crisis. The CCP and the Carmonas were in trouble. Gemi was crying in a convent in Miami, Bebo was sick in Santiago, yellow with hepatitis, caring for his father. The tumor was growing, and Quela, newly arrived in California, was saddled with proving her value to her kind but embattled host.

Chile and California are geographical inverts—Chile’s north is roughly equivalent to California’s south and vice versa—but Chile is longer, thinner, and far more dramatic. Chile’s Atacama desert, one of the driest places on Earth, makes the threat of California’s Death Valley seem hysterically overblown. California has the Sierras, but the Andes are home to Mount Aconcagua, which at 22,841 feet dwarfs Mount Whitney (a mere 14,505). The Andean condor is bigger than the California condor, and nothing in California compares to the natural savagery of Antarctica or the Strait of Magellan.

To the extent that national character is a function of geography, then, Chile’s is structured less by the narrow spit of land it actually is than by the vast structures that enclose it on either side. The Andes and the Pacific isolate Chile from its neighbors, and they also make it difficult to psychologically detach from the sublime.

Still, these are both regions characterized by their giant winged birds, strings of mountains, and miles of coast—not to mention a fertile central valley, unstable geology, active volcanoes, and improbably rich mineral stores. Both are a little in love with their own legend, and both cultivate—and appreciate—certain kinds of infamy: If Mackenna failed to charm New York, he succeeded in California, where he proved his value as an ambassador of Chilean moxie. He even pranked the Spanish government by arranging for it to intercept a fake letter bearing his signature, which ostensibly described the movements of Chilean privateers. The Spaniards fell for it, to the delight of the Americans—Californians especially: The April 13, 1866, edition of the Sacramento Daily Union gleefully reports that “the expense to the Spanish Government of the fool’s errand upon which these vessels were dispatched, owing to the ruse played by the Chilean envoy, is estimated at $30,000.”

Reagan repeatedly sidestepped Patrick DeYoung’s requests to meet to discuss the Chile–California Program, confining his response to a slashed budget. DeYoung planned a trip for a VIP group that would include outgoing Governor Pat Brown and, crucially, a Reagan representative who would evaluate the program’s work in Chile. The trip had to be perfect. DeYoung’s letters and invitations to various functionaries were unflaggingly cordial, but the sheer mass of his output tells another story. There are Hail Marys among the carbon copies, including a letter addressed to Conrad Hilton inviting him to experience the Chile–California Program for himself.

Newly arrived in Sacramento, Quela was determined to take what little social capital she had and spin straw into gold, throwing a Hail Mary of her own: She told DeYoung she could arrange for him and whomever Governor-elect Reagan appointed to evaluate the program to meet Jorge Alessandri—the ex-president of Chile whose door she had knocked on in a moment of desperation.

It’s the kind of boast not even prankster extraordinaire Benjamín Vicuña Mackenna would have made. I imagine Quela, alone and middle-aged, sitting at the table of the Californian family she’d persuaded to host her, writing to the Chilean who made her presence there possible. Her hair is perfect as she composes her letter to the ex-president. It, too, had to be perfect. It had to recast her as a helpful liaison rather than someone who threw herself at his mercy. The ink had to alchemize the desperate need that once drove her to Alessandri’s doorstep into a chatty, even slightly arrogant presumption of friendship.

It’s imaginative jiujitsu. It’s political witchcraft. And it worked.

Here is the ex-president’s response agreeing to her kind proposal that he meet with the visiting gringos: “You may express that he will receive them with the greatest pleasure if he is in a position to do so,” Alessandri’s letter reads, speaking in a grand—and quite Chilean—third person.

Quela followed up on her miraculous social coup by asking her son, Bebo, to wait on the DeYoungs hand and foot during their visit. His letters are consumed with the details of his preparations. The DeYoungs might have been royalty. If these letters show middle-class scheming at its most aspirational, they also register how badly the Carmonas needed a goal to knit them back into a unit. So much depended on the gringo visit to Chile: DeYoung’s job, Adolfo’s tumor, Reagan’s decision, Chile’s fire departments, the future of the Carmona family.

Twenty years old, missing his mother, sick with hepatitis, saddled with an ailing father, Bebo accepted the challenge to be the host his mother couldn’t be. When the DeYoungs arrived on January 10, 1967, Bebo was at the airport waiting for them with a dozen roses, his girlfriend Inés, and his friend Nivaldo (a member of the air force who ushered the DeYoungs through customs quickly). Bebo’s letters narrate each miniscule increment of social leverage. His gestures were like ants, utterly disproportionate to the weight they were meant to lift, but (and this was Bebo’s insight as he studied for his engineering exam) it all depends on where you put the fulcrum. As the Chile–California Program letters became more dreamily aspirational, accosting Hiltons and future presidents, the Carmona letters, no less hopeful, swarmed into smaller and smaller details. “At first we didn’t know which ones they were,” Bebo writes of trying to find the DeYoungs at the airport, “but Nivaldo looked at the labels on the luggage and discovered which were theirs.”

He writes his mother about the moment they finally met: “We introduced ourselves, Inés gave Mrs. Jean the roses and a kiss—she [Mrs. Jean] found her ‘beautifull, beautifull.’”

He invited the DeYoungs to the Carmona house “for a drink,” but Bebo also shared his mother’s eye for bigger things. What he envisioned was not a drink but something finer, a party. His preparations for the DeYoungs resemble Clarissa Dalloway’s. “I had to wax the entire first floor,” Bebo writes to Quela, “mend the curtains, dust the picture frames and lamps, shake out the shams and pillows on the furniture, and remove that giant portrait of Queli because it’s ugly.”

This is what a twenty-year-old boy writes to his mother a world away in 1966, trying to muster her party-planning perfectionism. The father’s tumor is growing. He will buy the flowers himself. “I bought: gin, pisco, chips, peanuts and salted almonds, juices, ginger ales, those tiny little Chilean pastries and lemons to prepare pisco sour. I went to Ines’ and she brought me cups and wineglasses, a pitcher, trays, and paper napkins. I also invited Nivaldo.”

These were significant expenditures. Bebo’s letters were as much about money as they were about anything else. The party represented not just social risk but entrepreneurship, investment, interest. Bebo went to fetch the DeYoungs at their hotel. They kept him waiting half an hour and he pretended not to mind. “I paid for the taxi,” Bebo writes. The smallness of the sentence reverberates with stretched resources.

The much-anticipated visit lasted a mere fifteen minutes. The DeYoungs had to go—they had a dinner party to attend.

They ate nothing. Not the chips, not the peanuts, not the almonds, not the cakes. But Bebo narrated those fifteen minutes to his mother with all the Hollywood glamour he could muster. “Nivaldo helped me prepare the drinks,” he writes. “He made them with these sugar decorations on the glasses—they looked beautiful. The gringos loved them.” And the party, such as it was (or wasn’t) bloomed into spun-sugar strands of possibility: Patrick DeYoung asked Nivaldo whether he’d considered taking some courses in the United States. Nivaldo “nearly hit the roof,” Bebo says. They were all suddenly full of hope.

As I read the official archive of the Chile–California Program and the private archive of my family’s relation to it, I realized that this is the sort of nebulous benefit the Chile–California Program conferred. My family’s arrival in California depended on Quela meeting Patrick DeYoung in an elevator—on an ex-president’s mood, on the sugar decoration on a drink, on a label, a taxi, a hope. The moments on which my existence depends don’t even rise to the status of transactions. They were simply occasions for something to spark when something did. That’s all a party is, in the end; it’s all diplomacy is, too.

A haze of granted wishes hung in the air after the gringos left, taking with them their small talk and questions that nearly strangled Nivaldo with hope. The “party” would not be a failure if Nivaldo went to flight school in Oklahoma, if Adolfo made it to California, if the geodesic dome managed to close over them once again.

“Everything we’d prepared was left over,” Bebo writes, “so between Tata, Inés, Nivaldo and I we ate everything.”

The Chile–California Program died a few months after the party in Bebo’s living room. Reagan’s second in command, William P. Clark, would eventually dismiss the program as “untenable and corrupt.”

A stunned and disappointed Patrick DeYoung returned to Lockheed in 1967. Nivaldo never made it to Oklahoma.

Quela had arrived just in time for the Chile–California Program to end, but she’d started teaching Mexican farm workers about health and hygiene. A series of Spanish-language instructional pamphlets that she wrote and illustrated was published and circulated widely among migrant communities. She became a valuable asset to public-health programs looking to reach Spanish-speaking populations. It was in this capacity that my father, an American physician who spent his spare time opening free clinics for migrant workers, met her. (She instantly recruited him to give her female students a talk about family planning and birth control.)

Quela rebuilt the stability she’d lost. She brought Adolfo to California. She brought her daughters, Gemi and Queli, back from Miami to California. She even brought my mother to Sacramento to keep Gemi company. She wrote editorials about family values for the newspaper. She spoke on the radio. She started a restaurant.

But the effort took its toll on the Carmona dome: Bebo never fully reentered it. He remained in Chile with Inés and created a life of his own. The urgent attention to detail with which he showered his mother in those early letters dwindled and slowed into a calloused and laconic privacy. His letters got shorter; some years, there are no letters at all.

Quela, for her part, wrote regularly to her “friend” Jorge Alessandri, urging him to run for president again. She mourned when Salvador Allende beat him in the 1970 election. She panicked when Fidel Castro visited Chile. And she cheered when, on September 11, 1973, the military junta overthrew the Chilean government.

Adolfo’s tumor proved to be inoperable. He remained blind.

On September 11, 1973, Augusto Pinochet led the Chilean army into La Moneda, the Chilean presidential palace. Salvador Allende died, and so did Chile’s reputation as a stable democracy. My mother was in Sacramento with Quela, Gemi, Queli, and Adolfo when the military coup took place. They were desperate for news and distressed at American coverage that—in their view—made Chile seem like a lowly, disorganized banana republic.

Liliana, who was in her office in Santiago when the coup took place, wrote a detailed and celebratory account of it to her anxious relatives in Sacramento. Quela wrote back with a proposal: that the two sisters (both of whom, remembering the losses their family sustained in Cuba, became avid pinochetistas) join forces to fix Chile’s public-relations problem in California. “I’ve thought of a plan and I want you to help me put it into practice,” she writes. It was time to explore whether “the government of Chile would have interest in reviving the Chile-California Program.”

What follows in the letter is an incantation of Quela’s social influence, a litany of half-true networks. Quela’s gift for alchemizing her connections had grown. “Tell him I’m great friends with the first director of that program,” Quela writes, her prose gathering a mesmerizing rhythm. “Tell him I’m known to the governor and the vice-governor.” Her vision for the resurrected Chile–California Program was huge: It would include technical assistance, increased agricultural production, the development of frozen, dehydrated, and canned goods. Tourism. A chain of motels.

“Tell them,” she says finally, “that you have been invited to visit by the Department of Labor Relations in California”—there had been no such invitation, but she would will it into being—“and that this organization would offer a good model for Chile. After what you’ve lived through, I think you certainly deserve some vacation time here. Offer to come here to explore everything I’ve just listed. It’s time for us to do something that takes advantage of my being here.”

Once again, Quela’s visions are astonishing not just because of their scope—her unbelievable, Andes-inflected, gold-mining leaps of faith—but also because they worked. My grandmother honored her sister’s call from across a continent and followed this blueprint. The Gonzalez force field proved even stronger than the Carmona one: It even sucked dictators in.

On December 14, 1973, a mere three months after he’d overthrown the legally elected government, Augusto Pinochet interrupted a hectic schedule of consolidating power and disappearing dissidents to obediently dispatch my grandmother to California to “explore the possibility of reactivating the Chile-California Program for the Reconstruction of the Nation.” He never guessed he was following the instructions of his old neighbor from Ortúzar Street.

As when Bebo prepared for the DeYoungs, the nonnegligible outcome was a party. My grandmother arrived in Sacramento, ostensibly on affairs of state. She was accompanied by her sister Elisa, the oldest of the Gonzalez sisters. The ingredients for the Chile–California Program were in place. Quela threw a reception at her home that was attended by a senator and several members of the Chilean consulate. She arranged for my grandmother to meet with a senator at the capitol. There was pageantry: not the drums and fifes of the Hounds, but the flags and champagne flutes of a trio who understood, better than most, the imaginative dimension of diplomacy.

But after meeting with the important men and posing on Pico Way, the three sisters climbed into bed, grinning at the Chile–California Program they’d somehow managed to believably resurrect, if only for an evening.

Across the thick fog that separates Chile and California, my father, Quela’s boss, saw my mother, Quela’s niece. When my grandmother left California, my mother decided to stay. They married, had me, and had a host of other ideas, including, I recently discovered, a “Chile-California Society” of their very own, complete with official letterhead bearing our home address.

I don’t know what this particular Chile–California Society was for. My parents don’t remember creating it. But it’s fitting, in a way, a blank piece of official stationery. An instrument designed for projection, it’s the four-person “party” with sugared drinks that might—if the fifteen minutes go well—result in someone going to Oklahoma to flight school, or someone else’s sight being restored. It’s both the blankness and the blindness of trans-American potential.

Truth is tricky in my family, where the teller’s ratio of malice to goodwill means a great deal more than anything as prosaic as evidence. There are rumors, for instance, that Adolfo was never actually blind—that one day he simply tired of working and took to his chair, and pronounced himself sightless. Quela’s brother—the one who was imprisoned in Cuba—called him “Ojos de Águila”—Eagle Eyes—behind his back.

Poor Adolfo’s medical records did little to convince this faction; on the whole, we Gonzalezes prefer to preserve the nonsense we love—the Chewed Potatoes and John Jokebutts—over dull or tragic truths. My Californian half, the beleaguered side that respects the dry impartiality of facts, has struggled to verify these renegade stories. It’s hard. You have to chase down the rumor and pin it to something real—a certificate, a photograph, a letter, an archive. That’s been my work here.

But sometimes even the archives lapse into lunacy. As the Chile–California Program was wrapping up, a key functionary, preparing grimly for the end, compiled the challenges that remained: Someone had donated an ambulance. Someone else donated a Holstein bull. Her letter to a colleague begins with logistics and dissolves into fantasy. “I want to put the bull in the ambulance and ship them off together,” she writes. “Can’t you just see the headlines in the California papers with a picture of the bull in the driver’s seat? It would say something like ‘Bull leaves for Chile in Ambulance.’ Of course, the bull would have to be smoking a big black cigar and waving out the front seat of the ambulance. Then as they arrive in Chile the picture would be somewhat different. The bull would be pictured lying down in the stretcher and the caption would have to read ‘It’s been a long trip.’”

I sympathize with the impulse to stick the bull in the ambulance and ship it away, to combine life’s millstones and dispatch them, pulverize them, bury them underground. But that wasn’t Quela’s way: If Adolfo never really got out of his stretcher, Quela never really stopped waving out the front seat. And when the ambulance that sped the Carmonas to California stalled out, she bought a Valiant and taught herself how to drive.

In 2008, President Michelle Bachelet visited California in honor of a new agreement between California and Chile (it would be a “pact” this time, not a “program”) with Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger. Quela traveled to Davis for the occasion, tack-sharp, spine curled from age. And at the reception, the Gonzalez myth once again hatched into fact: Quela, who was never formally involved with the Chile–California Program, was publicly hailed by President Bachelet as one of its most important members.

No one corrected the record. Like Vicuña Mackenna—who nodded as the Travellers Club pronounced him ambassador, senator, and author extraordinaire—Quela, proud, nearing ninety, smiled and leaned into the truth-making power of the presidential hug. The photograph only shows her back, but those who saw her say her eyes were twinkling.