1.

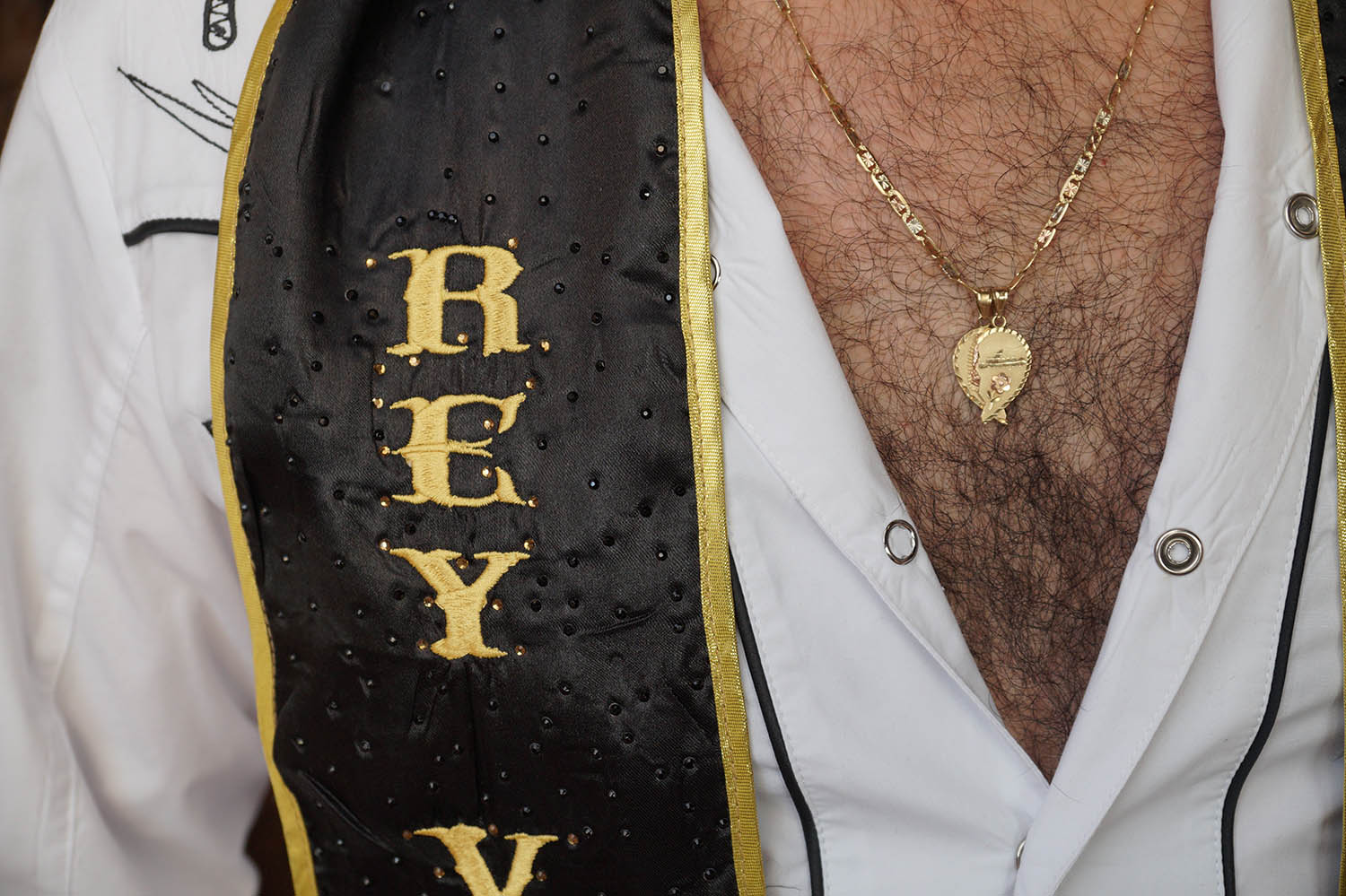

The weekend of El Grito (the Scream), when Mexico celebrates its rebel yell against Spain, is also the weekend when the season’s first pilgrims arrive in the town of Real de Catorce, high on a sun-blitzed mountaintop in the deserts of San Luis Potosí, and the weekend when 300 gay cowboys convene there to choose their Cowboy King, the Rey Vaquero de Real. José Sotelo, California’s 2016 Rey Vaquero, arrives on the second day of the party, a black-and-gold sash draped over his shoulders to match his black beard, black mirrored aviators, black-and-gold Tejano, and the two golden halves of a heart—one inscribed with his name, the other with his partner’s—nestled in a shrub of black chest hair.

The weekend of El Grito (the Scream), when Mexico celebrates its rebel yell against Spain, is also the weekend when the season’s first pilgrims arrive in the town of Real de Catorce, high on a sun-blitzed mountaintop in the deserts of San Luis Potosí, and the weekend when 300 gay cowboys convene there to choose their Cowboy King, the Rey Vaquero de Real. José Sotelo, California’s 2016 Rey Vaquero, arrives on the second day of the party, a black-and-gold sash draped over his shoulders to match his black beard, black mirrored aviators, black-and-gold Tejano, and the two golden halves of a heart—one inscribed with his name, the other with his partner’s—nestled in a shrub of black chest hair.

He wades into a sea of cowboy hats, kissing cheeks and chatting with men he sees a couple times a year at one of the dozen other conventions held annually in Tijuana, Juarez, Vegas, and Zacatecas, where he met his soon-to-be husband two years ago. “My grandparents were farmers, but I moved to the city when I was an adolescent. I miss that life,” he tells me, meaning the wild life of the countryside. “I identify with that life—and with this community. These guys are from cities, but they identify with it, too, with the past that they don’t get to live anymore.”

In Real de Catorce, they live a weekend-long fantasia of nostalgic masculinity. For a few days, doctors and stylists and designers, men who would never wear Tejanos and boots on an ordinary day, embody the revolutionary romantic, roaming free over the open expanse of a nation still willing itself into being, searching for love through the sights of a rifle. In the country, you roam freely. For queer Mexicans, it takes the city to love freely. Here, for a few days, you can do both.

To put on the costume is to enter a space of play, where the sexual freedoms of Mexico’s urban future peacock in the gaudy masculinity of the rural past. You pose for pictures at the ruins of an old mine, ride on horseback and laugh at off-color jokes, and, by night, dance to banda, arms sheathed in pink paisley entwined across broad backs, pointed boots tapping against old cobbles.

2.

Arriving in Real de Catorce, I change out of my ratty jeans and flannel into my own vaquero outfit: white Tejano, snap-front shirt embroidered with lassos and horses, brown ankle boots. I clack down uneven streets, past racks of tiny amulets in the shape of legs, feet, and hands, offered by pilgrims to the image of St. Francis: They’re called milagritos, little miracles, and each one is a wish for healing. “What do you think of all this?” I ask a woman selling votives by the roadside. “You mean las vaqueras?”—the cowgirls? She laughs. “It’s very nice.” She’s only teasing, but I blush nonetheless, painfully visible, plainly seen.

Arriving in Real de Catorce, I change out of my ratty jeans and flannel into my own vaquero outfit: white Tejano, snap-front shirt embroidered with lassos and horses, brown ankle boots. I clack down uneven streets, past racks of tiny amulets in the shape of legs, feet, and hands, offered by pilgrims to the image of St. Francis: They’re called milagritos, little miracles, and each one is a wish for healing. “What do you think of all this?” I ask a woman selling votives by the roadside. “You mean las vaqueras?”—the cowgirls? She laughs. “It’s very nice.” She’s only teasing, but I blush nonetheless, painfully visible, plainly seen.

Later that day, in an abandoned chapel, Gerardo and Héctor pose for pictures in front of a faded mural of a pope, a cardinal, and a king writhing naked in hellfire. “In clubs in Monterrey,” Gerardo says, “you see guys who don’t have a hair anywhere. They’re passive, obvious, tight pants and no shirts. Vaqueros look like men.”

Hairless. Passive. Obvious. The great sins against queer machismo. Mainstream gay culture remains obsessed with masculinity, and not only in Mexico: bottom-shaming, femme-shaming, the culture of “Masc4Masc” on gay-sex apps, the flamboyant aping of overt masculinity, which is also a joke at masculinity’s expense. Think of the Village People, of pride parades, of the chiseled bodies in Chelsea, a moving exhibition of the male form. The difference here is distance, both spatial and temporal: The “manly” past is still nearby.

And so here the joke plays differently. On the street there’s no kissing, no holding hands, a willing concession to the traditional mores of country people who still, for many, represent the best of what Mexico can be. Behind closed doors, we cheer at competitions for best kiss and most sexual positions simulated. We vote for Rey Vaquero based on YouTube videos of cow-milking and live line-dancing. We’re participants in a pageant of masculinity that is also a joyous affront to it. Tight pants and cowboy hats. Men who like men who look like men. Men who pose at empty altars, hips flung out, collars of their lilac shirts open to the navel.

3.

The first time I see Joel Grimaldo, he’s slamming his boots against the bulging cobbles as he dances to the raucous clatter of banda, all swirling brass and hooting tuba. His worn vest and silver-capped teeth and sun-scarred face are a dead giveaway: He’s the only real cowboy in Real de Catorce.

The first time I see Joel Grimaldo, he’s slamming his boots against the bulging cobbles as he dances to the raucous clatter of banda, all swirling brass and hooting tuba. His worn vest and silver-capped teeth and sun-scarred face are a dead giveaway: He’s the only real cowboy in Real de Catorce.

We meet the following day at lunch. Everyone wears a number; anonymous notes are passed. Someone writes, “35: Quiero besarte.” I’m number 35; I have no idea who wants to kiss me. Joel shows me the broken bottoms of his boots. “I have others but these are my favorites,” he says.

Joel lives two hours downhill in Matehuala, the closest town to Real. In his late twenties (he’s forty-two now), Joel traveled across Mexico with a folkloric dance troupe. That crazy cowboy tarantella, he tells me, is traditional to Monterrey. Now he works at a cattle ranch, managing the horses. “That’s how I live, working all the time,” he says, “and to have fun I dance.” He plays a video of himself dancing on the bleachers of Matehuala’s baseball field, beer in hand, a small audience cheering him on like a jester. “See?” he says, “they’re shouting ‘Vaquero! Vaquero!’”

His voice drops to a whisper. “There are other gays in Matehuala, but they’re all ‘obvious.’ I don’t want people to see us together and get to talking.” To be seen with the “obvious” boys would confirm his secret. Who would cheer “vaquero” for him then? The only person not in costume wears the deepest disguise.

Joel started coming to the Rey Vaquero weekend two years ago, the only place where he can be his full self: cowboy, dancer, gay. His only other interactions with gay people are via WhatsApp, pictures and messages exchanged furtively with men ten years his senior. “You know why I like older men? Because I never had a father’s love,” he says. “My father died when I was four, so I never had a father to hold me”—he grips my shoulder—“or brush my cheek”—he brushes mine.

That night he’s the first one dancing, same tattered boots, Tejano held high. He spins wildly around his own tilted axis, smiling maniacally, a smile that his dark, gaunt face can hardly contain.

4.

Real de Catorce has two churches, the large one in town, and the abandoned one in the cemetery where St. Francis, known affectionately as Panchito, made his first mysterious appearance three centuries ago, borne in wooden boxes on the backs of mules. Among the town’s many legends is that of the saint’s leather sandals, worn through after nightly walks from his home in town to the cemetery chapel, where he tended the graves.

Real de Catorce has two churches, the large one in town, and the abandoned one in the cemetery where St. Francis, known affectionately as Panchito, made his first mysterious appearance three centuries ago, borne in wooden boxes on the backs of mules. Among the town’s many legends is that of the saint’s leather sandals, worn through after nightly walks from his home in town to the cemetery chapel, where he tended the graves.

Every night of the weekend, when the band stopped playing and the crowd had thinned, the remaining vaqueros in their evening finery made their way to the saint’s first home to drink beer among the graves, a bit of joy to share with the dead. By day, they removed their hats in church, Catholics who’ve reached an accord with their god: We believe in and love you in the knowledge that you believe in and love us back. A contract of mutual respect, like the one they’ve made with the townspeople in Real. Mexico’s Catholicism, even here in the conservative north, is a capacious thing, with space for burning cardinals and gay cowboys and angels with the faces of Indians.

On my first day in Real, before most of the vaqueros had arrived, I went to see the saint. The pilgrims—half pious, half in the guise of piety—had yet to arrive en masse. By the next morning they would crowd Real’s handful of streets, as transfixed by sweets and toys and pomade of peyote as by the supposed sanctity of this former seat of colonial capital. Consumption as faith, faith as consumption.

Half a dozen people knelt in the pews. Another half dozen took family photos at the altar, frozen half-smiles in place of the cowboys’ studied, brooding pouts. The saint himself sat above them, enclosed in glass, surrounded by flowers, on a golden throne. His face looked sad, almost stricken. Milagritos—golden amulets pinned like promises to his dull brown robes—looked, from a distance, like jewels. The humblest of saints gilded with wishes. Here, even Francis wears his finery.

5.

Not everyone wakes up for the trail ride to a ghost town high in the hills over Real de Catorce, but about sixty cowboys are there in hats and sunglasses, hiding hangovers. “None of us have lived on ranchos,” Juan Carlos Gomez says of his fellow vaqueros as he mounts a tall chestnut. Even still, everyone seems comfortable on horseback, city boys who spend weekends in the longed-for country, country boys who’ve moved to the city but keep the mountains in their bones. “In Mexico, we’re still in transition,” Gomez says. “Everything is a mix between rural and urban.”

Not everyone wakes up for the trail ride to a ghost town high in the hills over Real de Catorce, but about sixty cowboys are there in hats and sunglasses, hiding hangovers. “None of us have lived on ranchos,” Juan Carlos Gomez says of his fellow vaqueros as he mounts a tall chestnut. Even still, everyone seems comfortable on horseback, city boys who spend weekends in the longed-for country, country boys who’ve moved to the city but keep the mountains in their bones. “In Mexico, we’re still in transition,” Gomez says. “Everything is a mix between rural and urban.”

Up in the ruins, looking down on Real, cupped between the iron-red hills, Pedro tells me about his childhood in Veracruz, a sprawling state on the Gulf Coast. “I emigrated from a village, mostly cattle farms and ranches. It’s beautiful there, but the farther from the city you get, the more conservative it is,” he says. “In the country you believe what your grandmother tells you. She says something is bad, that means it’s bad.”

That night, under spinning neon lights, a guy called Eric tells me, “Everyone looks more handsome in boots and a hat. I see a guy dressed like that, and I think, es un hombrezote.” I hadn’t felt like “a big man” for most of the weekend. I’m used to passing, announcing my sexuality when it suits me; in Real, I was one of the “very nice cowgirls,” the happy brigade parading giddily in chambray and mesh, leather and rhinestones, respectful but obvious.

Back home in Mexico City, there’s a club called Marrakech, a tiny room crowded mostly with young guys, the kind of boys who wouldn’t come to a vaquero weekend, who wield their queerness like a weapon, who can turn a punchline into a pistol. On the wall there’s a painting that has become famous in the decade since Marrakesh opened, making its rounds as a meme on social media. It’s an image of a nubile man leaning against the long neck of a white horse. He wears Pancho Villa’s sombrero and mustache, his round ass pushed out in the saddle, eyes closed in rapture: passive, obvious, beautiful.

This project was made possible with support from the Eisner Foundation and KCRW.

These dispatches are from #VQRTrueStory, our social-media experiment in nonfiction, which you can follow by visiting us on Instagram: @vqreview.