The German word heimat has no direct English equivalent. The closest analogue is “homeland,” but even that fails to capture the particular way in which the German people integrate a sense of place with national identity, and the degree to which that identity is passed from one generation to the next.

As a child of the 1980s, artist Nora Krug belongs to a generation that, while separated by decades from World War II and the Nazi regime, nonetheless inherited the sins of the Holocaust, a generation whose “paralyzing guilt,” as Krug describes it, was ingrained through cultural and academic ritual—through school field trips to concentration camps, rhetorical analyses of Hitler’s speeches, and an unspoken agreement to erase words such as ethnic, race, and hero from its speech.

As an adult living abroad, Krug carried this historical burden with her, experiencing almost daily confrontation with her German identity through an accumulation of awkward introductions, awkward silences, taking pains to hide her accent—dodging one way or another—and coping with the “familiar heat” of shame she felt whenever she considered herself in the context of others’ judgment. “In German society, you learn a lot about the war but you don’t feel compelled to face the issue as an individual. Nobody asks you where you’re from. When you live abroad, you’re constantly asked where you’re from, and when you say Germany there is, understandably, this association with our Nazi past.” This tension, meanwhile, was always in the context of citizenship; her grandparents never talked about the war or their role in it.

As an adult living abroad, Krug carried this historical burden with her, experiencing almost daily confrontation with her German identity through an accumulation of awkward introductions, awkward silences, taking pains to hide her accent—dodging one way or another—and coping with the “familiar heat” of shame she felt whenever she considered herself in the context of others’ judgment. “In German society, you learn a lot about the war but you don’t feel compelled to face the issue as an individual. Nobody asks you where you’re from. When you live abroad, you’re constantly asked where you’re from, and when you say Germany there is, understandably, this association with our Nazi past.” This tension, meanwhile, was always in the context of citizenship; her grandparents never talked about the war or their role in it.

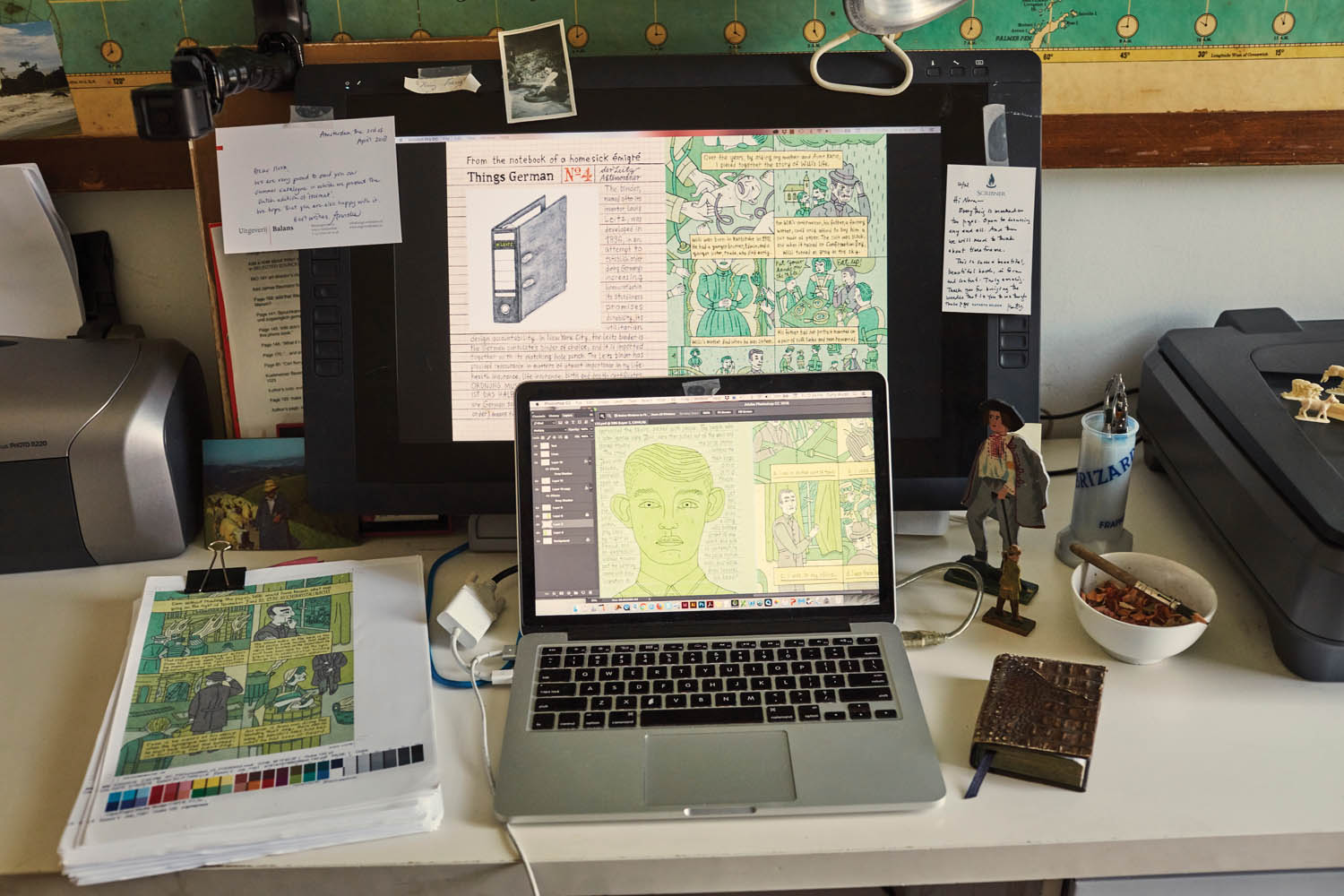

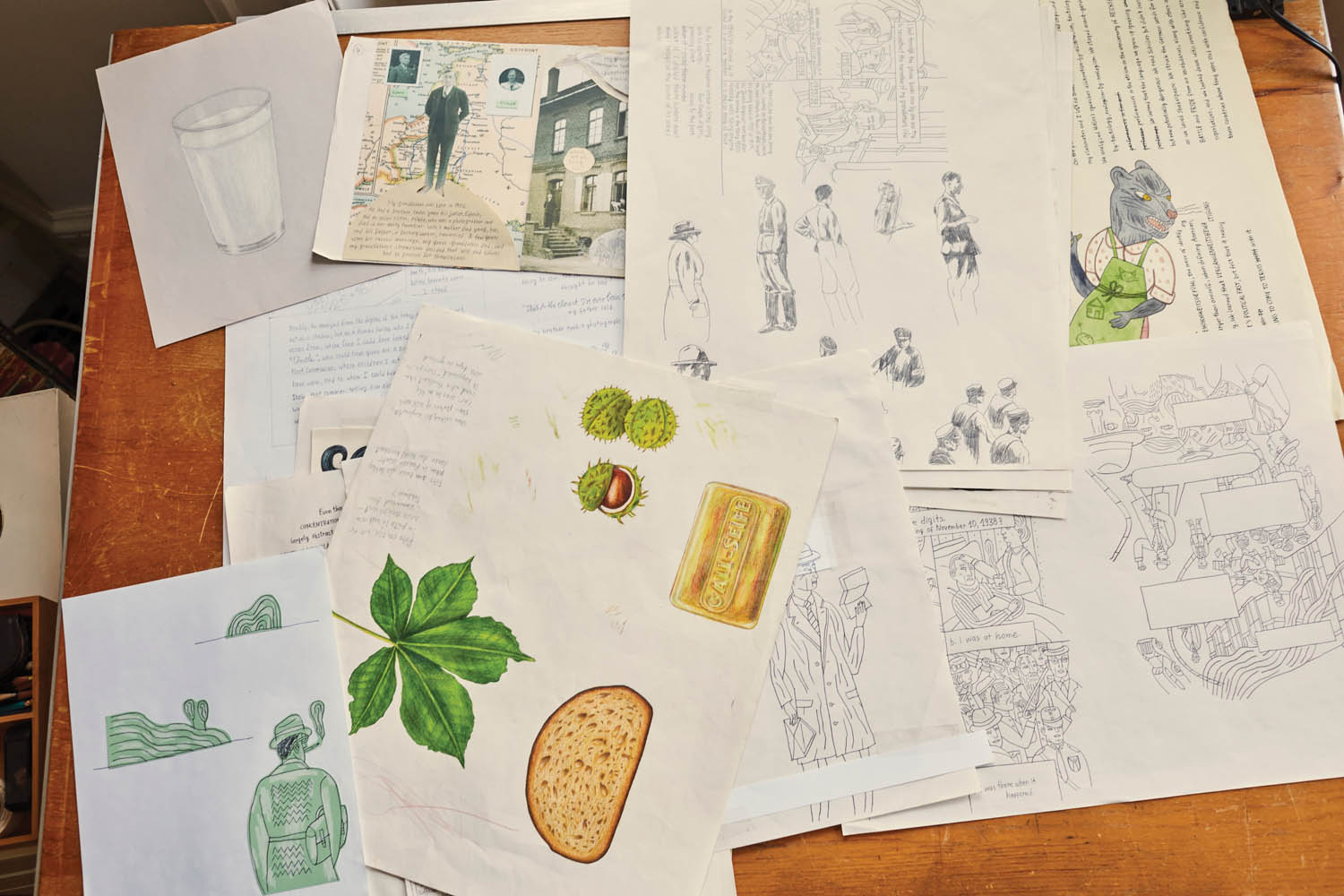

After nearly twenty years of wrestling with this inheritance, Krug chose to face certain fundamental questions head-on: What exactly was her family’s role during the war? Did they belong to the Nazi Party? Did they participate in the persecution of Germany’s Jews? And if not, were they complicit by doing nothing? Belonging is the culmination of her investigation, what Krug describes as a “visual memoir” comprising photographs, illustrations, documents, and handwritten passages that form an intense scrapbook of historical and emotional excavation.

After nearly twenty years of wrestling with this inheritance, Krug chose to face certain fundamental questions head-on: What exactly was her family’s role during the war? Did they belong to the Nazi Party? Did they participate in the persecution of Germany’s Jews? And if not, were they complicit by doing nothing? Belonging is the culmination of her investigation, what Krug describes as a “visual memoir” comprising photographs, illustrations, documents, and handwritten passages that form an intense scrapbook of historical and emotional excavation.

The book came together in slow phases, beginning with two years of research—delving into archives, visiting the home village of her uncle, a teenage SS officer, interviewing neighbors who knew him, browsing flea markets in search of wartime ephemera, “because my own family never left me any of those things, and I wanted to get a more visceral sense of what it was like to live under the Nazi regime.” She spent another two years writing, “just trying to figure out how to weigh the personal and the political, the present and the past.” Once she had the structure down, she spent another two years illustrating. “I chose a medium based on what I wanted to say on a given page,” she says, “what the mood of the moment was going to be, or how I wanted to weigh the images and the text against each other.”

Krug says she never perceived the book as an act of atonement—the Holocaust, of course, is impossible to reconcile; for any German to entertain the notion of absolution would be, as she puts it, “wildly inappropriate.” Nonetheless, her exploration is vital for several reasons that go beyond an accounting of ancestral guilt.

Krug says she never perceived the book as an act of atonement—the Holocaust, of course, is impossible to reconcile; for any German to entertain the notion of absolution would be, as she puts it, “wildly inappropriate.” Nonetheless, her exploration is vital for several reasons that go beyond an accounting of ancestral guilt.

“I think we all need to recognize ourselves as carriers of our country’s past,” she says. “We can’t pretend that we exist in a vacuum. We carry the memory of wars and political events, and these memories are passed from generation to generation. We have a responsibility to watch what we do with these memories. We have to be able to learn from these things and apply them to the present—and we have to be very careful and aware of how easily language can be abused, how easily we can lose our grip on democracy. These things happen, sometimes, very quietly, and we need to be alert and try to fight for these values.”

— Paul Reyes