I was selling holy trinkets

I was dressing kind of sharp

Had a pussy in the kitchen

And a panther in the yard…

The first poem in Leonard Cohen’s posthumous book The Flame made me laugh. Not because the lyrics are especially funny (although there are touches of Cohen’s characteristic wry humor), and not because the poem is foolish (it’s quite good), but because it is practically a medley of every single theme and obsession Cohen took up over his sixty-year career. Holiness and pussies are just a start. One almost senses him (knowingly, always knowingly) ticking off boxes. Angels and devils: check. Art, sartorial elegance, and slaves: check, check, check. Messianism: check:

I was always working steady

But I never called it art

The slaves were there already

The singers chained and charred

…………………………

Go tell the young messiah

What happens to the heart

—“Happens to the Heart”

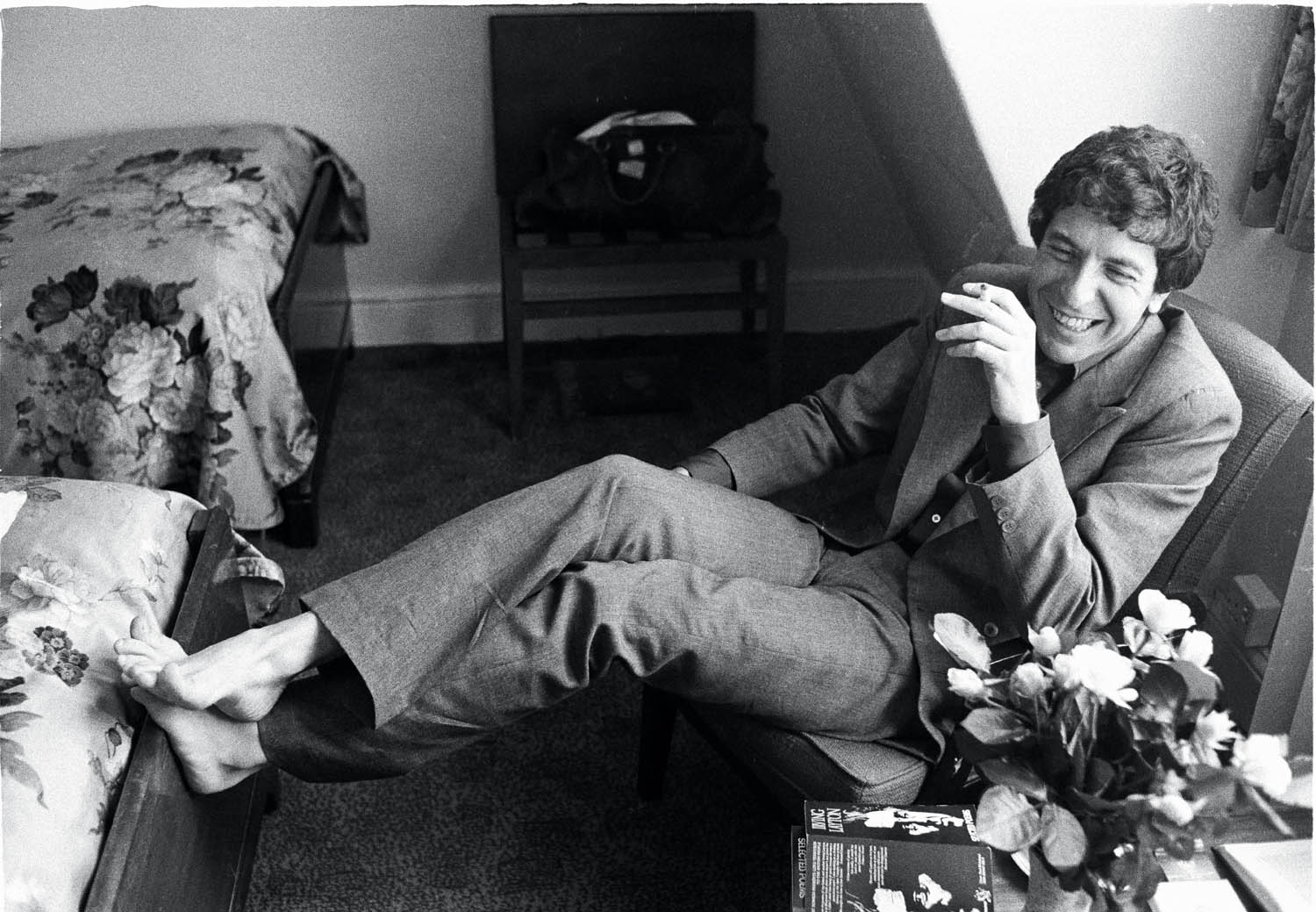

The Flame, which Cohen finished only days before his death in November 2016, is a collection of poems (most new, some old but never previously published), lyrics, drawings, and working notebooks. Cohen’s celebrity exploded in the last decade of his life; fans may come to this book unaware that it is merely the last in a long line of novels and poetry collections that Cohen published, that in fact he launched his reputation in print and not in song. He could have had a very fine career as a novelist, but he got sick of not making any money. By the mid-1960s, he was “starving,” by his own report, despite critical acclaim and a devoted following in his native Canada: “It was very difficult to pay my grocery bill.” In 1966, after a decade of publishing, he turned to songwriting.

Some of Cohen’s followers know this story (and that he had, at the time, also written four well-received volumes of poetry). Few have read the novels. There are two. The Favorite Game (1963) is a highly stylized and poetic account of youthful male friendship and early sexual experience with women. It won the Prix Littéraire du Québec and was praised as “tremendously alive” and “extraordinarily rich in language, sensibility, and humor.” Beautiful Losers (1966) is as unfettered as The Favorite Game is controlled: deliberately excessive, crude, and ridiculous. Cohen himself, in a 1965 letter to his publisher, called it “a tasteless affront” and “an irrelevant display of diseased virtuosity.” (He also said it possessed “incomparable beauty,” and was correct there, too.)

For lifelong devotees like myself—as a young teen, I spent hours listening to his LPs in my mother’s collection; when I left for boarding school, at sixteen, I stole them—there is perhaps never enough Leonard Cohen. A painstaking craftsman, he went several years between albums, not to mention the five-year hiatus he took in the mid-1990s to live as a monk at a Zen monastery outside of Los Angeles. That stint resulted in a nine-year wait between 1992’s The Future and 2001’s Ten New Songs.

It was probably inevitable that, as a novelist myself, and seeking more Cohen than the albums alone could give me, I would eventually turn to his fiction. To do so is not just for the Cohen completist. The Favorite Game and Beautiful Losers would be worthy of attention even if Cohen had never reinvented himself as a balladeer. The Favorite Game is a small jewel, and Beautiful Losers has the weird and destabilizing force of a gesture bordering on the insane. The novels draw from the same font as the music but stand in unique relation to them, like prisms that refract the same source of light.

Cohen put it slightly otherwise. Particularly in the earlier part of his career, when critics were more aware of him as both poet and singer, prose and songwriter, he spoke about the lack of distinction, for him, between the various genres. The music was the poetry was the prose. In 1966: “[Distinctions between] all those kinds of expression are completely meaningless. It’s just a matter of what your hand falls on and if you can make what your hand falls on sing then you can just do it. If someone offered me a building to design now, I’d take it up. If someone offered me a small country to govern, I’d take it.” In 1968: “I just see the singing as an extension of a voice I’ve been using ever since I can remember. This is just one aspect of its sound.” And in 1969: “There is no difference between a poem and a song. Some were songs first and some were poems first and some were situations. All of my writing has guitars behind it, even the novels.”

Cohen never published another novel after 1966, the year before his first album was released, but in 1993 he published Stranger Music. It was subtitled “Selected Poems and Songs,” yet included passages from Beautiful Losers as well as excerpts from 1984’s Book of Mercy that are neither distinctly poetry nor prose. In 2006 came Book of Longing,which featured not just poetry and prose-like selections but drawings and odd little images that have the flavor of computer clip art. The Flame is very similar to Book of Longing in composition, with the priceless addition of the drafting notebooks. To know Cohen’s music alone is not to know the fullness of the man’s art—is really not even to know the fullness of the music.

The Favorite Game is the typical coming-of-age first novel raised to high artistry by a born poet and would-be prophet. It has a grave, formal humor and charm. Its protagonist is Lawrence Breavman, which comes off the tongue rather as “Leonard Cohen” does; the name Breavman suggests resonances from “brave” to “bereaved” and sounds appropriately Jewish. In the novel’s pages we encounter figures and happenings corroborated as autobiography by Cohen in various interviews and by Sylvie Simmons in her excellent and empathic 2012 biography, I’m Your Man. There is the World War I–vet father who dies when Breavman is nine, and the anecdote in which Breavman, after the funeral, buries his father’s bowtie with a written message tucked inside it: his first piece of writing as letter to the world. There is the flamboyantly emotional and increasingly unstable Russian-born mother, and the grandfather and uncles who are founders and pillars of the Montreal Jewish community.

The novel opens with a description of scars: those on a lover’s earlobes from an ear-piercing gone wrong; one left by a German bullet in Breavman’s father’s arm; one on Breavman’s temple, the result of being smacked with a shovel by his best friend, Krantz, during a childhood fight over building a snowman. (Even as little boys these two characters are known only by their last names, as if they are Laurel and Hardy or Abbott and Costello.) The novel is preoccupied with wounding, above all the wounding that desire brings, and with the exciting and distressing hints children get of the sexuality and violence waiting for them in the adult world.

As Breavman gets older, the story turns to the beauties and perils of sexual intimacy. He falls into a love affair with a woman named Shell, oscillating between a happy thralldom and a panicked desire for flight. There is a casual sexism in The Favorite Game that marks the novel as being of its era, although Breavman sometimes notes and objects to it, as when a fellow counselor at a summer camp job starts a betting pool on who will be the first to sleep with a particular woman coworker. (Despite his objection, Breavman ends up participating.) He describes one of his lovers as having a mouth that “belongs to everyone, like a park.” Nevertheless, the descriptions of the female body could be written only by someone who adores its every form, and the women in The Favorite Game have real personalities and subjectivities. Shell, who has been married to a man who doesn’t desire her sexually, believes her body is disgusting. Breavman’s patient work to teach her to take pride and pleasure in it is touching. But Cohen does not let his avatar off the hook. He’s onto Breavman’s grandiosity and the way he demands constant availability from women but will not offer it in turn. To one lover, Breavman confesses: “I want to touch people like a magician, to change them or hurt them, leave my brand, make them beautiful. I want to be the hypnotist who takes no chances of falling asleep himself.” (There is in fact a passage, again autobiographical, where Breavman successfully hypnotizes the family maid into taking off her clothes.)

No summary of the novel can get at the precision and power of its language, the way it swerves and then homes in on the kill. To quote Isaac Babel, Cohen is a writer who knows that “no iron can stab the heart with such force as a period put just at the right place.” Of Breavman’s father: He “lived mostly in a bed or tent in the hospital. When he was up and walking, he lied.” But the novel’s highest achievement is to convey the divine and ecstatic in the flow of ordinary life. Not just sex but a nighttime drive with a friend, a walk in the park, or a passionate conversation can be an experience of the sublime. In a 1994 interview, Cohen explained that the famous line in “Suzanne” in which the singer is fed “tea and oranges that come all the way from China” grew out of a visit in which the wife of a friend served Cohen a cup of Constant Comment. Constant Comment, the ubiquitous tea of my childhood! Indeed it is flavored with orange rinds (the tea itself comes from South Carolina). Cohen’s confession was revelatory: To get from Constant Comment to oranges that come all the way from China, I realized, simply requires a confident willingness to mythologize.

The sublime in Cohen is never very far from laughter. Breavman and Krantz really are Abbott and Costello much of the time, verbally feinting and jabbing, getting up to hijinks. “Two Talmudists,” they engage in “ten thousand conversations” blending the philosophical and the absurd, stalk the streets for girls, attend political meetings and fall away from them. Krantz eventually becomes the more conforming member of society, while Breavman abandons the job Krantz gives him and runs away to an uncertain future. He wants to be capable of loving his lover, his friend, and his mother, and has begun to fear that Krantz is right, that he is “unavailable.”

There is a great deal to dislike about Beautiful Losers, as Cohen himself noted, and I disliked it intensely the first time I read it. The plot is simple. A perceptive Goodreads reader once posted that it could be summed up with a line from Cohen’s “The Partisan,” his 1969 reworking of a French Resistance song: “There were three of us this morning / I’m the only one this evening / but I must go on.”

For his autobiographical novel, Cohen uses a third-person narrator; for the majority of this fantasia he uses two first-person narrators. The first, who describes himself as an aging scholar, never receives a name; the other, known only as F., dictates about a third of the book, though from the grave: His words are in a letter opened only after his death in an insane asylum. As with Breavman and Krantz, the two narrators are inseparable from youth. They grow up together in an orphanage, one of them English, one French; they even take the same long nighttime car rides Breavman and Krantz do—with the added detail that they masturbate each other during them. F. is the master/teacher/dominator in the pair; the scholar is the acolyte/submitter. As in Cohen’s “Famous Blue Raincoat,” the two friends share a woman: The scholar is married to Edith, a member of the Iroquois tribe he studies; F. has an affair with her. At the age of twenty-four, Edith kills herself.

At the center of the scholar’s narrative is his obsession with Catherine Tekakwitha, a seventeenth-century historical figure and Montreal’s unofficial patron saint; her figurine, the narrator tells us, appears “on the dashboard of every Montreal taxi.” Also an Iroquois who died at twenty-four, she was known for her virginity and her zeal at self-mortification, so extreme that she essentially flogged and starved herself to death. In 1980, she was beatified; in 2012, she was canonized by Pope Benedict XVI. Here are the opening sentences of the novel:

Catherine Tekakwitha, who are you? Are you (1656–1680)? Is that enough? Are you the Iroquois Virgin? Are you the Lily of the Shores of the Mohawk River? Can I love you in my own way? I am an old scholar, better-looking now than when I was young. That’s what sitting on your ass does to your face. I’ve come after you, Catherine Teka-kwitha. I want to know what goes on under that rosy blanket.

This goes on for a while in the same vein; then, in the next paragraph:

I am a well-known folklorist, an authority on the A_____s, a tribe I have no intention of disgracing by my interest. There are, perhaps, ten full-blooded A_____s left, four of them teen-age girls. I will add that F. took full advantage of my anthropological status to fuck all four of them.

Sigh. To get through Beautiful Losers you have to get through a good deal of pedophilia and some rape, mostly of girls and women. This is one of the reasons I was less than enthusiastic upon my first reading. It is difficult, today, to stomach the way the girls and women in it are portrayed as “cunts,” a word freely and frequently used. The scholar and F. are complex and suggestive characters (some readers have theorized that they may even, in fact, be the same person); Edith has no interiority whatsoever. The old scholar marries her when she’s sixteen; she is purely a body, an initiator of or receptacle for sex. She may, the reader suspects, be the reincarnation of Tekakwitha, but that doesn’t rescue her from a fatal thinness of characterization. She exists so that the two men (or one-man-as-two) may play out their fates. Any other women who incidentally appear are also, simply, sexually available bodies.

Yet Cohen’s prose in this novel is spectacular, a manic mashup of prayer, harangue, exultation, dirty talk, and panic that is dizzying but in no way sloppy. (Cohen later reported that he was strung out on amphetamines during its composition. In addition, as he wrote in a wry introduction for a 2000 Chinese translation of the novel: “Beautiful Losers was written outside, on a table set among the rocks, weeds and daisies, behind my house on Hydra, an island in the Aegean Sea…. It was a blazing hot summer. I never covered my head. What you have in your hands is more of a sunstroke than a book.”) The novel blends historical accounts of French–Indian warfare and Catholic evangelism with cartoon sound effects (“Pow! Sock!”), reproductions of advertisements, and free-associative appeals to God that lift off into tragicomic poetry: “You Know the Details of the Kangaroo. Place Ville Marie Grows and Falls Like a Flower in Your Binoculars. There are Old Eggs in the Gobi Desert. Nausea is an Earthquake in Your Eye. Even the World Has a Body. We are Watched Forever. In the Midst of Molecular Violence the Yellow Table Clings to Its Shape.” The novel most often has a cartoonish aspect: To commit suicide, Edith sits at the bottom of an elevator shaft and lets the descending car crush her. There doesn’t seem to be any gore associated with this, and right afterward the narrator and F. eat takeout.

The most outrageous part of the novel is an extended scene in which Edith reports to F. that she can no longer have an orgasm. F. reads to her from “a swollen book, frankly written, which describes various Auto-Erotic practices as indulged in by humans and animals, flowers, children and adults, and women of all ages and cultures.” After covering such material as “Why Wives Masturbate” and “What We Can Learn From the Anteater,” F. turns to the “unusual sex practices.” Over many, many pages, Edith perches on the verge of orgasm as F. continues with entries including “Detailed Library of Consummated Incest” and “Cannibalism of Oralists.” Finally, after Edith begs him to “do something… but don’t touch me,” F. offers a “torture story” describing how the Iroquois (Edith’s ancestors) gruesomely killed two Jesuit priests. When Edith still doesn’t come, F. pulls out “the Danish Vibrator,” a device with a “White Club,” a “Developer,” “Fortune Straps,” “Formula Cream,” and other mysterious appurtenances. He goes into a bizarre monologue about his attempts, Dr. Frankenstein–like, to re-create Edith and her husband, the scholar, as perfect beings. Edith finally comes, and the vibrator, which though unplugged has acquired a life of its own, penetrates F., now “ready to submit,” and then mounts Edith. When finished, it jumps out of a window and motors itself to the beach, where it disappears into the ocean. (“Will it come back, F.? To us?” asks Edith. “It doesn’t matter,” replies F. “It’s in the world.”)

On completing the manuscript, Cohen promptly had a breakdown. He spent a week in the hospital and claimed to have memory lapses for a decade afterward. Jack McClelland of McClelland & Stewart, Cohen’s primary publisher, wrote to him: “I’m sure it will end up in the courts.… You are a nice chap, Leonard, and it’s lovely knowing you. All I have to decide now is whether I love you enough to spend the rest of my days in jail for you.” McClelland took the chance. The reviews were at best equivocal. The Toronto Daily Star said it was “the most revolting book ever written in Canada” but also “the most interesting Canadian book of the year.” The Globe and Mail said it was “verbal masturbation.” Kirkus Reviews declared itself “at a dead loss to define or defend” the novel. Beautiful Losers sold very few copies until Cohen was an established recording artist and it was given a paperback release. Then it became a campus favorite, and has since sold more than 3 million copies. (This seems to contradict my claim that few people have read it, but I rarely meet anyone who has, or even knows about it. Europeans, who have always embraced Cohen more consistently than Americans, perhaps account for the majority of copies. The novel has appeared in at least a dozen languages.)

On my second reading of Beautiful Losers, I could anticipate the elements that would offend me. I knew I’d come across a scene in which all three characters take a bath using a bar of soap apparently made from the fat of exterminated Jews. I knew I’d once again dislike the passage where Edith, age thirteen, is chased through the woods and raped. I knew I’d dislike it even more when the scholar-narrator, in relating this incident, says, “Follow her young young bum” and “Edith, forgive me, it was the thirteen-year-old victim I always fucked.” With my outrage a bit numbed, I could let the language, the sacrilege, and the wild energy pour over me and acknowledge its somewhat satanic power. And I could see more clearly an aspect of Cohen’s songwriting that is more obvious in the novels: the acceptance of, and sometimes willing participation in, violence and cruelty.

The title of The Favorite Game refers in part to a game that Breavman and Krantz invent as boys surrounded by the propaganda and news reports of World War II. Their neighborhood friend Lisa becomes a captured American; they, the Nazis, “torture” her by whipping her with a red piece of string against her bare buttocks. When older, Breavman and Krantz titillate each other with the worst examples of torture they’ve gleaned from war accounts. And there is an incident with a frog, which starts with a drunken Breavman declaring, “We’re in charge of torture tonight,” and ends, post-vivisection, with, “I suppose that’s the way everything evil happens.”

During his early musical career, Cohen acknowledged a fascination with warfare: “War is wonderful,” he said in a 1974 interview, having flown to Israel in the hope of being accepted into its army after the surprise Yom Kippur invasion. “They’ll never stamp it out. It’s one of the few times people can act their best.” In The Favorite Game, the young Breavman is obsessed with his father’s army pistol, and thrilled by a fight at a local dance hall. (“He threw his fist at a stranger. He was a drop in the wave of history, anonymous, exhilarated, free.”) Violence removes self-consciousness and painful strangerhood. Afterward, we read:

He would love to have heard Hitler or Mussolini bellow from his marble balcony, to have seen partisans hang him upside down; to see the hockey crowds lynch the sports commissioner; to see the black or yellow hordes get even with the small outposts of their colonial enemies.

Good causes, bad causes, it doesn’t matter: Human beings will always seek a rationale for mayhem. Cohen neither condemns nor celebrates this. Irving Layton, a prominent Canadian poet and early friend and mentor of Cohen, once commented that Cohen was “one of the few writers who has voluntarily immersed himself in the destructive element, not once but many times, then walked back from the abyss with dignity to tell us what he saw.” Cohen himself once said, “I’ve always honored both the wrathful deities and the blessed deities.”

In Beautiful Losers, violence moves to the center. The book is not emotionally realistic or moving in the way The Favorite Game is. But in its oddly cerebral and oddly carnal way, it explores something urgent. Biographer Simmons sums up Beautiful Losers as “a prayer—at times a hysterically funny, filthy prayer—for the unity of the self, and a hymn to the loss of self through sainthood and transfiguration.” Well, maybe, but all I’m sure of is that Tekakwitha embodies some outer limit of the embrace of suffering, and illustrates how strangely self-assertion and self-abasement can be intertwined. Tekakwitha asserts herself ferociously by ferociously abasing herself, burning her flesh with hot coals for hours, refusing food, sleeping on a mat of thorns.

When Cohen turned from novels to songwriting, he continued to employ the vocabulary of sainthood and violence, of dominance and submission, but to different effect. Compare Beautiful Losers to Cohen’s gorgeous early song about a different saint, “Joan of Arc”:

Now the flames they followed Joan of Arc

As she came riding through the dark;

No moon to keep her armor bright,

No man to get her through this very smoky night.

She said, “I’m tired of the war,

I want the kind of work I had before,

A wedding dress or something white

To wear upon my swollen appetite.”

Here, with simplicity and concision, Cohen conveys the dignity, loneliness, and human passion of the saint. I find it impossible to identify with Tekakwitha, but I can’t help identifying with weary Joan, so recently a farmer’s daughter doing chores, expecting to marry. She is caught, like many Cohen heroes and heroines, between the sacred and the profane, unable to live fully in either realm. Later, the singer conflates martyrdom and sexual passion, suffering and ecstasy:

“And who are you?” [Joan] sternly spoke

To the one beneath the smoke.

“Why, I’m fire,” he replied,

“And I love your solitude, I love your pride.”

“Then fire, make your body cold,

I’m going to give you mine to hold.”

Saying this she climbed inside

To be his one, to be his only bride.

…………………………

It was deep into his fiery heart

He took the dust of Joan of Arc,

And then she clearly understood

If he was fire, oh then she must be wood.

In the very last lines of the song, the singer steps out into the narrative and merges with the figure of Joan: “Myself, I long for love and light / But must it come so cruel, and oh so bright?” He knows that love brings burning. In “Joan of Arc,” female martyrdom is no longer pornographic but an occasion for empathy, an event with universal resonance.

In the lilting, fairytale-like 1984 song “Night Comes On,” Cohen wonders (hopefully, it seems) about when his lover, the mother of his children, will leave him: “I needed so much to have nothing to touch / I’ve always been greedy that way.” If Tekakwitha was transformed into Joan of Arc, who was transformed into Leonard Cohen, now Cohen is transformed back into someone with longings for sainthood. For what is a saint but someone who needs to have nothing to touch, who pushes away human intimacy and comfort for a higher devotion? In “Night Comes On,” sainthood takes on an aspect that is less absurd and monstrous, is revealed as an ordinary ambivalent human tendency.

Cohen was especially fond of metaphors of masters and slaves in his early work; one of his poetry collections is titled The Energy of Slaves. More often dominated in his novels, in his songs women sometimes become the masters/dominators. This is not unproblematic. When I was sixteen, listening to “One of Us Cannot Be Wrong,” I wanted to be the woman of whom Cohen sang: “I lit a thin green candle / to make you jealous of me.” I wanted my nakedness to be a force a man was desperate to pitch himself into:

An Eskimo showed me a movie he’d recently taken of you

The poor man could hardly stop shivering, his lips and his fingers were blue

I suppose that he froze when the wind took your clothes

And I guess he just never got warm.

But you stand there so nice in your blizzard of ice

Oh please let me come into the storm.

It didn’t occur to me that the woman doesn’t seem to be feeling much: She is static, perhaps frozen herself. I was distracted by the power she possessed. And when Cohen “tortured the dress” that the “you”“wore for the world to look through,” I felt the hint of slut-shaming, but it only added an extra frisson. When the male protagonist takes up the position of supplicant/slave, the woman gets to be a cunt in a different way. This wasn’t enough, though—and still isn’t—to keep me from superimposing myself onto the women in Cohen’s songs. Like Shell in The Favorite Game, who learns to see herself through Breavman’s adoring eyes, I feel my femaleness become impossibly beautiful and potent through Cohen’s worshipful, if at times also resentful, lyrics. The resentment only ratifies the hold the female has on him.

Throughout his singing career, some of Cohen’s audience has insisted on seeing him as the melancholy, soft-hearted balladeer, a sensitive, pacifist type. The main website devoted to Cohenania, Cohencentric, lists the three subjects that regularly trigger negative reactions from site readers. These are “His Scientology Phase,” “His Guns,” and “His Perspective on War.” The misunderstanding of certain aspects of Cohen’s character and art is partly due to his public persona: careful, formal, soft-spoken, a Buddhist. But another cause must surely be the astonishing loveliness of Cohen’s melodies. When Cohen began to write songs, those melodies took the sometimes bombastic and dour words of his poetry and fiction and brought them buoyancy and tenderness and even joy. As a teenager, living one summer in France, I discovered that when speaking French to French people (rather than to my US school classmates), my voice became different: higher, sweeter, more stereotypically feminine. More startlingly, my thoughts organized themselves somewhat differently. I was a different person in French, a function purely of how my mouth needed to move in order to make different sounds. Cohen became a different artist when he began producing melodies as well as words. Music drew on the more affirmative part of his soul, the part crystallized for many listeners in Cohen’s most widely covered and best-known song, “Hallelujah.” Even in his great, embittered albums of the late 1980s and early 1990s, I’m Your Man and The Future, his arrangements created an effect of jauntiness. “Everybody Knows” combines lines like “Everybody knows that the Plague is coming / Everybody knows that it’s moving fast” with a thrillingly menacing beat and a sexy Spanish guitar. The even more nihilistic “The Future” (“I’ve seen the future, brother / it is murder”) is up-tempo, with a swaying backup chorus and a cheerful call-and-response with gospel harmonies. Over and over, Cohen’s linguistic and melodic brilliance merge to make a more perfect art.

In 2016, Bob Dylan, who ought to know, told David Remnick of the New Yorker that Cohen’s melodies were “genius.” “Even the counterpoint lines—they give a celestial character and melodic lift to every one of his songs…. His gift or genius is in his connection to the music of the spheres.” Dylan went on to analyze the key changes and structure of the iconic “Sisters of Mercy” (1967): “It’s so subtle a listener doesn’t realize he’s been taken on a musical journey and dropped off somewhere.”

“Mercy” happens to be a favorite term in Cohen’s music, as in his poetry. An artist who believes that violence and defeat are inevitable—and tempting—will also yearn for the presence of mercy. Another instructive prose-versus-song comparison is between 1984’s Book of Mercy, a collection of short pieces based on the Book of Psalms, and “If It Be Your Will,” a song from the same year. Both are appeals, forms of prayer. Book of Mercy is stunning, a very personal liturgy for a new age. “I stopped to listen, but he did not come” reads the first line, and in the following pieces, fifty in all, the speaker attempts to fathom and converse with the divine. The exquisite “If It Be Your Will” is a vow of submission to God’s power, and its spare, slow, patient lyrics and rhythms (particularly if you listen to the countertenor cover version by Antony) evoke the celestial quality Dylan speaks of. There is both a deep seriousness and a lightness to the song; the psalms in The Book of Mercy can’t help but lack the lightness. The Book of Mercy is not a lesser creation, but it has less lift. As his career went on, Cohen began more and more to employ his women backup singers as an independent chorus instead of blending their voices with his own (about which he was always insecure). This chorus—epitomized by the ethereal-sounding Webb Sisters, who toured with him between 2008 and 2013—became counterpoint and echo; Cohen was the sound of Earth and the chorus that of the heavens. He had solved, at least musically, the conflict between the two realms that tormented his poetry and fiction.

The Flame is Cohen’s last gift to us. While readers are unlikely to find themselves memorizing its poems as listeners do his songs, it contains deep pleasures. Cohen’s radical honesty and wit became more refined and purified with each passing year. “I think I’ll blame / my death on you / but I don’t know you / well enough / If I did / we’d be married by now” reads “I Think I’ll Blame.” From the notebooks: “I’m troubled by war / I’m troubled by peace / Can’t they think of anything else.” The devastating “My Career” consists entirely of three lines: “So little to say / So urgent / to say it.” There are the familiar invocations of slaves and masters and the transience of love, but there are also references to antidepressants, Kanye West, and Skype. The last lines of the collection refer to “a mandate from God / to enter the dark.” As if he fears appearing too earnest at times, Cohen sprinkles the pages with very funny self-portraits in which his face seems to be 90 percent wrinkles and sagging jowls. Gazing at these, one has the sensation of climbing into Cohen’s body and experiencing his constant self-distrust and bewilderment, not to mention his awareness of approaching mortality.

With its fragments and diaristic entries, The Flame illuminates the process by which Cohen moved from words on the page to Dylan’s “music of the spheres.” After he emerged from his years in the monastery on Mt. Baldy, he produced two (relatively) minor albums, Ten New Songs (2001) and Dear Heather (2004), before his great end-of-career triad: Old Ideas (2012), Popular Problems (2014), and You Want It Darker (2016), released seventeen days before his death. In these, Cohen turns more insistently to the theme of mortality. But he didn’t fasten on the title Old Ideas for nothing. In that album’s opening song, “Going Home” (in which “home” is clearly the afterlife), the singer unabashedly describes himself as God’s prophet: a “tube” that speaks the words God tells him to. Lawrence Breavman fancied himself as hypnotist, magician, and prophet; Cohen here (and not for the first time) claims that mantle. As always, it’s difficult to sort out how serious or ironic he is. In “A Street,” from Popular Problems, Cohen draws from his ample bag of war metaphors:

You put on a uniform

To fight the Civil War

You looked so good I didn’t care

What side you’re fighting for.

And in “Treaty,” on You Want It Darker, the association of love with war, and the posture of indifference to the justice of any given conflict, comes up again:

I wish there was a treaty we could sign

I do not care who takes this bloody hill

I’m angry and I’m tired all the time

I wish there was a treaty, I wish there was a treaty

Between your love and mine.

In You Want It Darker’s title track, Cohen addresses God with the phrase “Hineni,” Hebrew for “Here I Am,” the words with which Abraham replies to God’s summons of him in Genesis. In this case, Cohen seems to mean that he’s ready to be called from earthly life. A low, sinister drum line conveys a sense of dread, but the opening plainchant-like chorus and the solo by Gideon Zelermyer (the cantor from Cohen’s childhood synagogue in Montreal) counterpose the sound of trust and devotion against that dread. Cohen returns to his lifelong view of the cruelty and violence inherent in human nature:

… it’s written in the scriptures

And it’s not some idle claim

You want it darker

We kill the flame

…………………………

I didn’t know I had permission to murder and to maim

You want it darker

Hineni, hineni

I’m ready, my lord.

Never afraid to be sacrilegious, Cohen accuses God of reveling in humankind’s destructive tendencies, of wanting human beings to “make it darker.” At the very least, God does nothing to prevent our most despicable actions. But who is Cohen to gainsay God? He bows to the stronger one: “I’m ready, my lord.”

If Beautiful Losershad been a critical and commercial success in 1966, would Leonard Cohen have gone on writing novels? It’s impossible to say. That book—magnetic but exhausting, its pleasures sometimes as hard-won as Edith’s orgasm—perhaps represented a writerly point beyond which Cohen could not go, making the turn to songwriting a necessity for artistic as well as financial reasons. Or maybe he would have found yet another way to reinvent the novel form. Maybe he simply didn’t want to. Instead, he developed another version of his voice, bringing to it an even greater range of expression. Humor and celebration were always present in Cohen’s fiction and poetry, but he enabled us to hear them far better in the music. He magicked and mastered us after all, getting us to clamor for the bitter pill of his tender, scathing, suffering, beatific vision.