After chatting about his child’s food allergies for ten minutes, that distinctive ache has stirred at the back of my throat. Yet I say nothing. The restaurant manager has been kind. He prides himself on taking care of customers like me. Because a reaction often begins with swallowing—repeated, reflexive—I drain a glass of water and finish my wine. Vegan cuisine conveniently avoids dairy and egg, beef and shrimp, but steers me smack into the path of cucumbers, mango, tofu, tree nuts. The sauce I thought was tahini might be cashew butter. I put the wrap down and take a Benadryl. I take another Benadryl a minute later. I leave most of the second sauvignon blanc on the table and tip big.

After chatting about his child’s food allergies for ten minutes, that distinctive ache has stirred at the back of my throat. Yet I say nothing. The restaurant manager has been kind. He prides himself on taking care of customers like me. Because a reaction often begins with swallowing—repeated, reflexive—I drain a glass of water and finish my wine. Vegan cuisine conveniently avoids dairy and egg, beef and shrimp, but steers me smack into the path of cucumbers, mango, tofu, tree nuts. The sauce I thought was tahini might be cashew butter. I put the wrap down and take a Benadryl. I take another Benadryl a minute later. I leave most of the second sauvignon blanc on the table and tip big.

I walk out alone. I arrived alone. It is a Sunday night in South Beach and I don’t live in South Beach, or Miami, or even Florida. I have a full twenty-block walk ahead but if I don’t move my car before getting help, it’ll be towed by tomorrow morning.

I get behind the wheel. As I turn from the quiet of Washington Avenue to the buzz of Collins, I realize I cannot drive. The friend I call on my cell phone can’t make out my words as I describe my location. I yank myself out of the right lane and into the driveway of a fancy hotel, open the door, and vomit onto the pavement. When I look at the startled valet, the first thing I say is: “I’m not drunk.”

Where is your EpiPen? I have had the epinephrine injector with me the whole time—at the restaurant, on my walk, in the car, at the hotel, and in my friends’ car as they drive me to the hospital. I have carried an EpiPen in my purse, carrying that purse room to room wherever I go, for almost thirty years. I just don’t opt to use it. Again.

Sheldon Kaplan, a biomedical engineer who also designed a medical kit for the Apollo Moon Missions, patented the device that became the “EpiPen” in 1977. A spring-loaded needle releases epinephrine directly into muscle, ideally the fleshy thigh, where it acts more quickly than if ingested by pill or patch. The first crystalline epinephrine, created in 1897, was extracted from a sheep’s adrenal glands. Today’s version is entirely synthetic. Although the benefits of adrenaline had been observed for decades, including the ability to increase blood pressure and relax the muscles lining airways, it wasn’t until the 1960s that scientists identified receptor molecules that trigger these cellular responses. This research earned Robert J. Lefkowitz and Brian K. Kobilka the 2012 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

The EpiPen was approved by the FDA for commercial sale in 1987, seven years after I was born. It was prescribed for treating anaphylactic reactions, a phenomenon considered rare at the time, defined primarily in terms of cardiac distress and difficulty breathing. If you carried an EpiPen because you were allergic to bee stings, anaphylaxis was an imminent threat; you knew to inject yourself the moment you swatted at your skin and came away with a stinger in your hand.

If, like me, you carried an EpiPen as a bulwark against multiple food allergies—some severe, some mild, some still unknown—the guidelines were murkier. Every bite into a new fruit or vegetable was, and still is, a test of my system. Every bite into a prepackaged snack or restaurant dish carries the risk of cross-contamination. A food that does not trigger a reaction the first time I eat it might trigger a reaction the second time, or the ninth.

During childhood reactions, my lips would hive up, or my eyelids would swell. I might make a squonk-ee noise that my parents recognized as an effort to scratch my itching throat. I might feel “bubbles” of irritation along my esophagus, or queasiness in my stomach. I might feel feverish. If I’d eaten enough of the offending food, I would throw up, though usually I’d only had a single bite or two. Occasionally, the reaction began before I’d even swallowed.

Despite all these things, if I was coherent and alert, answering questions and neither hypoxic nor incontinent, we rode it out. I took antihistamines, usually Benadryl. Sometimes my grandfather or uncle, both naval doctors, would come by the house to check on me. I’d feel the cool moon of a stethoscope pressed against my breastbone.

Other times we decided to go to the hospital. The nursing staff did a lot of watching; we did a lot of waiting. Even after a first reaction recedes, many hospitals will hold you in case there is a second, biphasic reaction hours later. Epinephrine was a possibility, but more often I was administered a corticosteroid to suppress my immune system—the first of what would be several days’ worth of Prednisone. The dosing of Prednisone has improved since the eighties and nineties. Back then it was PMS in a pill, an instant gain of five pounds of water and ten pounds of bitchiness.

Often, if I tell stories of these reactions to parents, they ask, “And when did you use your EpiPen?” I pause, knowing I am about to disappoint them, and look across the divide of a generation. For them, epinephrine is first response. For us, it was last resort.

I meet these parents in bookstores, in schools, at literary festivals. We find one another because I’ve written a memoir that doubles as a cultural history of food allergy. “A memoir,” I remind them, “not a manual.”

Before the book, I had not spent much time with the advocacy communities around allergy. There were once two that dominated the American conversation—the Food Allergy & Anaphylaxis Network (FAAN), founded in 1991 and based in Virginia, and the Food Allergy Initiative (FAI), founded in 1998 and headquartered in New York. Though their missions looked similar in the abstract, they differed substantively in tone. FAAN was family-oriented, providing resources and guides for everyday life; FAI focused on policy and research. In 2012, they fused to become FARE: Food Allergy Research & Education.

In December 2011, I was invited to attend the Food Allergy Initiative’s ball in New York City. I would have been disappointed had I arrived at the gala expecting to eat from the prix fixe menu, but I would’ve also been naïve. I stopped for sushi on my way to the Waldorf Astoria. In the Grand Ballroom canopied with tiny lights, I demurred when offered dry-aged steak with “marrow mustard custard” and onion rings in a French wine sauce. I nervously adjusted the straps of my dress and made small talk. I was seated across from a renowned allergist; to be precise, I was seated across from his teenage son. Audra McDonald and Norm Lewis came out to sing selections from The Gershwins’ Porgy & Bess.

Later, I read that the 500 guests in attendance raised $4.5 million for the cause of food allergies. What is the cause of food allergies? Many in the room were focused on supporting studies of OIT, oral immunotherapy, and SLIT, sublingual immunotherapy. These treatments aim to desensitize patients through graduated exposure to an allergen. A successful trial outcome might be a peanut-allergic child who, after ingesting small doses of peanut flour daily, with slight increases every two weeks, for months, achieves a sustained tolerance of four grams: a dozen peanuts, give or take.

OIT and SLIT are experimental and time-consuming, with no data for their long-term efficacy. We are still in the early stages of adapting these procedures for those with multiple food allergies, or those at increased risk of anaphylaxis from even the slightest exposure. The cynic in me thinks of Whac-A-Mole—three years of my life spent acclimating to cashews, great. Now, what about pistachios? Milk? Shrimp?

But for those most likely to donate to food allergy research, immunotherapy offers a crucial commodity: the promise of a cure. I sat in the Waldorf Astoria surrounded by smart, wealthy, dedicated people who wanted very badly to fix their children. Which made me feel, in a way I had not before, just a little bit broken.

In 1973, Pentagon officials approached Survival Technology, Inc., Sheldon Kaplan’s employer. They needed a new kind of injection device. The stainless steel chamber used in existing injection designs was not a stable combination with certain nerve agent antidotes. Kaplan got to work. Four years later, his team was granted patent US4031893A for “Hypodermic injection device having means for varying the medicament capacity thereof.” Survival Technology delivered the ComboPen to the Department of Defense. They also readied the device for consumer sale as the EpiPen.

During the seventies, someone with severe allergies might have carried an Ana-Kit, introduced to the market by manufacturing company HollisterStier. The kit’s preloaded ampoules eliminated the guesswork of drawing epinephrine into a syringe in the middle of an allergic reaction; however, they did little to alleviate the anxiety of handling a needle. Kaplan’s injector both hides the needle, a larger gauge to punch through clothing, and amplifies the force with which it thrusts into the body. The toughest part might be steadying an EpiPen for the three full-Mississippi seconds it takes to deploy its contents. You can’t just swing and jab; people who jerk away have ended up with lacerations, the thick needle slicing through the skin.

In 1987, the average wholesale cost of an EpiPen was about $36. By the late 1990s, when I remember accompanying my mother to the pharmacy to refill our annual prescription for a single injector, we paid about $50. Sometimes we purchased an extra. This was a significant expense, but not an insurmountable one. Then in 2007, the EpiPen device was acquired by the Mylan corporation, as part of an aggressive global expansion that included purchasing the entire generics business of Merck KGaA (Kommanditgesellschaft Auf Aktien), as well as a controlling interest in Matrix Laboratories, which supplied active pharmaceutical ingredients. By 2009, a single EpiPen cost approximately $100. In just under a decade, Mylan turned EpiPens from a $200 million annual revenue into, at peak business, $1.1 billion in sales. Their product has a shelf life of little over a year, with most doctors prescribing the unit be discarded after twelve months from purchase. That’s a fruitful obsolescence—and arguably arbitrary, based on studies of potency in the months after the “expiration” date—but that has long been the case. How did Mylan grow its sales so expeditiously?

The surge in EpiPen purchases was, in part, a reflection of allergy’s growing prevalence in the population. A 2007 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention survey identified 4 percent of Americans under age eighteen as having food allergies; then a 2011 study, published in the journal Pediatrics, put the figure at 8 percent, or one out of thirteen kids. Most states, particularly after several rounds of lobbying at the congressional level, now permit (or, in some cases, require) school clinics to stock epinephrine injectors. Many private businesses, such as theme parks and cruise ships, have added them to their in-house dispensaries. I like to know EpiPens are nestled in first aid kits, just as I like to see automated external defibrillators on the walls at airports. But increased demand is just part of the picture.

In 2011, citing federal guidelines that advised carrying two epinephrine dosages at all times, based on case studies where patients continued to react after the first injection, Mylan discontinued the option of buying single injectors. Your kid misplaces one while at his soccer game and you can only afford one on this paycheck, but plan to buy another next month? Tough. Purchase two at once or none at all.

Other pharmaceutical companies attempted to clone EpiPen, but they weren’t very successful. Auvi-Q was recalled; the FDA cited a provisional model from Teva Pharmaceuticals as having “major deficiencies.” The Twinject was discontinued, eventually evolving into the Adrenaclick. Amedra Pharmaceuticals’ product had potential but little market muscle. After receiving a wave of public criticism and political pressure, Mylan finally released their generic version in late 2016; in 2018, the FDA approved Teva Pharmaceuticals’ model. But for years, EpiPen had 85 percent of the epinephrine injector market using a prohibitive price point.

When I came up to the register at the Kaiser Permanente on Capitol Hill to pick up my prescription in early 2016, the pharmacist shook her head and exhaled. “Did you know what this was going to cost?” she asked. $381.23. More than my paycheck. I paused for a minute, a minute that would have been punctuated by my mother’s howl had she been there to see me balk. Then I pulled out the credit card I’d been trying to pay off.

When I mentioned sticker shock to others later, people I didn’t even realize had allergies spoke up. One friend had been given an estimated price of $600 after insurance, $800 before. One of my students admitted she had never been able to afford an EpiPen. She tried to be within fifteen minutes of a hospital.

As with any medical condition, the individual narrative is shaped by class economics. Even if you’ve got a working EpiPen in hand, using it means a four- to twenty-four-hour hospital stay, which could equal a childcare crisis or losing a job. Recent studies in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia all show rising admissions for allergic reactions, with the highest incidence rate corresponding to younger patients. Perhaps that’s because of sheer volume; more children are allergic than ever before. Yet I wonder if twenty years from now, when those children have become adults in their own right, we will still see a leveling off of admissions in older patients. The truth is that the decisions our parents make for us are not the same decisions we make for ourselves.

A few years ago, I traveled to Georgia for the AJC-Decatur Book Festival. I met a friend before my afternoon panel—a reading from the food-allergy memoir—and we sat down for lunch at a farm-to-table restaurant that was a favorite of the participating authors. The roasted chicken with fingerling potatoes was delicious. Was it a touch too greasy-good? Only at the very end, as I sopped up the jus, did my lips begin to tingle. A faint rushing noise dialed up, a buzzing. I looked around to see if anyone else could hear it. My gut surged. I slipped a Benadryl into my palm, then my mouth. I kept talking to my friend and my friend’s friend, who was telling the story of a nasty divorce.

If I bailed on the panel, I would be violating my festival contract. Would they ask me to pay for the hotel room? There was no opportunity to delay, no do-overs.

I called the waitress over and, in the guise of praising the dish, asked her to describe the exact details of preparation. As she listed herbs and spices, stocks and vinegars and oils, nothing about the story had changed. The kitchen knew about my allergies. That meant the culprit was probably accidental, a dirty spoon or spatula. I swallowed hard, excused myself to the bathroom to scrub my lips with a wad of toilet paper, and went to my panel. When the next day’s lunch date asked about a location, I said, “I know a really good place.” I chose risks I had already encountered over risks of a new restaurant with an unfamiliar menu. To change it up, I tried the trout and couscous.

When caretakers dominate the advocacy conversation, disconnects are inevitable. Sometimes, this is a matter of demanding a service without fully anticipating the consequences: a parent insists on a “peanut-free” table for her child, but does not ask her child if anyone else is allergic. The child sits alone during every lunch for a year. Sometimes, this is a matter of not anticipating the need for a service at all.

One major oversight in the food-allergic advocacy community is alcohol. If a body is primed to react to an ingredient, the body does not care whether that ingredient is delivered via a fork or a martini glass. Olives come stuffed with everything from almonds (tree nuts) to blue cheese (milk) to anchovies (fish), which are three of America’s “Big-8” allergen categories. (The other five are eggs, crustaceans and shellfish, peanuts, wheat, and soy.) Labels on liqueurs and craft beers do not always clarify the source of their flavorings, nor are they required to, because the FDA does not oversee alcoholic products. Sangrias are topped off with cubes of mango and melon; pisco sours are foamed with egg white; garnish cutting boards and cocktail shakers are reused without anything more than a quick rinse.

The irony is that these dangers might be occurring at the very restaurants that pride themselves on being sensitive to food allergies. Often, a drink order is taken the moment the customer sits down—before he or she has even thought to share any dietary restrictions, or request a nut-free menu. In 2012, the National Restaurant Association released ServSafe Allergens, an interactive online training course designed to ensure restaurants have informed and sensitive staff. But nowhere in the program is bar prep a source of concern. All the attention is on front and back of the house, the waiters and the kitchen crew. The association consulted with FARE while creating the ServSafe program; How did no one flag this as an issue? But FARE, whose offices are dominated by concerned parents, tends to focus on threats posed to those under the legal drinking age.

When I wrote about this for a newspaper, a category of commenter threaded their sympathy with disdain. C’mon, they suggested, these are not inalienable rights. Skip the booze for a night. Maybe it’s stubbornness on my part. But after a lifetime of missing out on celebratory bites—Valentine’s chocolates, birthday cakes, Thanksgiving pie—I want to raise my glass and be part of the toast with everyone else at the table.

I’ve never been afraid of needles, but I am overly self-conscious about the bruises they cause, to the point of vetoing intravenous fluids. Phlebotomists have told me I’m a tough draw and that I should always request a butterfly needle and winged infusion set. Once, after a routine test, I came home and took a long bath. I held the punctured crook of my arm under the flow of hot water, not realizing the pressure I was putting on the fresh clot, and screamed when I saw blood flare wide under the surface of the skin.

For a hemophiliac, there is no such thing as a routine bruise or bleed. In Codeine Diary: True Confessions of a Reckless Hemophiliac, Tom Andrews reflects on the tension between being a writer who happens to have a disease versus being a diseased individual who happens to write. He recognizes the peril of setting himself up as a professional hemophiliac, “recklessly confident that I speak for all bleeders.”

He opens his memoir with a fall on the ice. What he should do is head straight to the hospital, cooling the injury along the way, to receive an infusion of factor VIII (a key blood-clotting protein) or Desmopressin (a medication that promotes factor release) as soon as possible. What he does, instead, is take the bus back to his apartment. He frames the unfolding narrative in these terms:

I have not chosen an “ideal” bleed. That is, there is much about my reaction to the traumatized ankle and about my interaction with doctors that I am not proud of. “Warts and all or not at all” was my guiding principle. There is occasional pettiness, and childishness, on my part. There is spinelessness. There is misguided anger. Above all, there is the flurry of thought and fear, which eventually gives way to the surprising, implausible surge of convalescence, the spirit’s if not the body’s, a convergence of self and world that opens one’s eyes to the mysterious in the familiar after a season in hell.

The “season in hell” is a hospital-bedded, codeine-mitigated haze during which he lavishes appreciation on his wife, riffs on John Ashbery and Joe Brainard, recalls setting a world record, and confronts memories of his brother’s death from kidney disease.

Andrews’s stream of consciousness during his initial emergency treatment disturbs me, but only because its extremes are so familiar. First comes what he calls the “reality orientation” exercises: the rehearsal of who you are, how old you are, where you are, who you’re with, why you’re there, and other willfully banal observations. I always do this aloud, as tangible confirmation that my airway is open. Then comes what he calls the “ontological breakdown,” the moment in which selfhood begins to slip. You become a metaphor, a construct. Your pain is a bow, sliding slowly across the neck of a violin. Though unlike Andrews, I’ve never then bargained for Darvon or morphine. Anaphylaxis frightens, but it doesn’t burn and pulse the way a fractured, bleeding joint does.

The final section of his memoir, “On Being a Bad Insurance Risk,” interrogates the social contract thrust upon those with chronic illness or disability. We heed. We obey. We comply with treatments based on what may be still-evolving science. Andrews receives transfusions on the front end of medicine’s comprehension of HIV as a blood-born disease. He ultimately tests negative, but his anxiety is palpable. “I can well imagine God’s spitting at my prayer of thanks for being passed over by AIDS,” he writes.

We are expected to be the best versions of ourselves. We are at the mercy of minor, chance events. “Once I lifted a gallon of milk in such a way as to break a blood vessel in my elbow,” Andrews writes. “The joint’s interior filled with blood until my elbow looked like a steroid-enhanced eggplant.” Once I sat down with my parents at an Italian bar, and we were offered a dish of olives. Who looks at a dish of olives and asks, “Are you sure these aren’t buttered?”

Andrews originally imagines his book closing with thoughts of John, his dead brother, and the notion of sea changes. He considers the pressure to “be well” while ill, meaning the societal emphasis that we must model wellness even while processing the “upheaval and danger” of disease.Instead, the book plunges ahead with the confession that Andrews, now divorced, has recently bought a Kawasaki KLX 250 bike. In his inaugural competition, he crashes four times. This comes twenty years after overshooting a corner in a motocross race, suffering a punctured calf muscle from the bike’s foot peg, and being begged by his parents and hematologist to stop. “I was about to race motocross again,” he writes, “because I needed to affirm that I was still an amateur hemophiliac, that I hadn’t turned pro.”

Is that what I’m trying to be? A resolute amateur? “Our culture urges people with chronic illnesses to resolve rich tensions,” he writes, “that to my mind are better left unresolved.”

Solutions of epinephrine are not supposed to be left in temperatures lower than 59 degrees or higher than 86 degrees. For some, that simply means protecting them while at the beach, or skiing, or other isolated occurrences. For others, the daily conditions of work—harvesting a field of corn, or pouring concrete at an outdoor construction site—render the auto-injector an impractical accessory even while it remains a critical one.

My husband, an artist, used to work an hourly wage job building rain gardens. We would make sure his lunches were vegetarian, because meat could spoil during the morning’s work. The first few times he mentioned wanting to call in sick because the temperatures were predicted to top 95 degrees, he took my silence as judgment. Not judgment so much as frustration, I told him. Two years into our joint insurance plan he still had not seen a doctor, meaning the $300 a month we paid on his behalf had gone entirely unused. He needed a physical. He needed a baseline measure of his health. He’s a man in his upper forties, and of course he should be careful of manual labor on a scorching day. My hypocrisy, as I said all this, was bitter in the mouth.

At age eleven, Tom Andrews got into the Guinness World Records by clapping his hands 94,520 times for fourteen hours and thirty-one minutes straight. He raced motocross; he practiced stand-up routines; he was diagnosed with hemophilia; he wrote Codeine Diary; he rode a bike again. He died in 2001, at age forty, after a coma related to contracting thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, a rare coagulation disorder. He had no health insurance at the time.

As an undergraduate at the University of Virginia, I read Andrews’s collection, The Hemophiliac’s Motorcycle. The experience was a kind of paradigm shift, as I began to consider how disability and chronic illness could shape an author’s voice rather than serve as a footnote. It would be a few years until I’d wrangle with the medicalized body on the page, in a sequence called “Allergy Girl.”

Years later, trading e-mails with a friend who had shared those undergrad workshops, we spoke openly of our respective illnesses for the first time: my allergies, his cystic fibrosis. Perhaps I should have guessed from his poem drafts, as if images of snow settling over branches are actually secretions blanketing the bronchi and alveoli. Or not. He had moved to Arizona, where he got an MFA, taught, ran a small press, and published chapbooks, including one titled L=u=N=G=U=A=G=E.

The cruelty of cystic fibrosis is that when a lung transplant becomes necessary—which it usually does, as function declines—both lungs must go. Otherwise, lingering bacteria can infect a fresh, healthy organ. My friend went into surgery at the end of 2011. On January 30, 2012, he passed away at age thirty-three.

“I almost die a lot,” I said once, for some forgettable reason, a quick quip for a laugh. For nights after, I sat with those words. I’ve weathered dozens of reactions over the years, which makes calling my condition “life-threatening” seem like indulgence. Few things annoy me more than when a well-meaning dinner companion interjects with an announcement to emphasize the seriousness of my requests: “She could die, you know.”

Yet the prescriptive attitude toward anaphylaxis is that any allergic episode can be the one that kills you. The formula for acceptable response is now rigid: You shoot the epinephrine. You go straight to the hospital. If you’re not amenable to those terms, it can be hard to know how to enter the societal conversation. Now, I have learned to be a bad patient, I wrote in a poem.

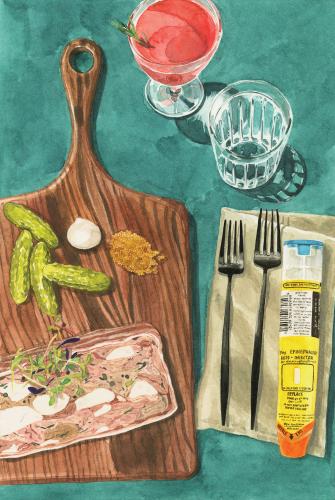

A few years back, I met my dad for happy hour on M Street, in northwest Washington. He had fed the meter for two hours, without a destination in mind, and we descended the steps to Vidalia. The Southern-themed restaurant was deserted that early in the evening and workweek. We ordered drinks and began to navigate the menu with the bartender, only to be interrupted by a curt, volcanic man wearing whites. He slapped a dishrag down on the counter. “What are you allergic to?” he asked.

I only got to mention the foods I always mention first—milk, egg—before he said, “You good with pig?” We nodded, and he disappeared. Twenty minutes later, he walked out with a terrine of pork. There were cornichons and mustard seeds on the cutting board’s side; I could eat around those. But what assurance did I have that there wasn’t another random ingredient? Shrimp, or beef? The man stared at us expectantly.

“Thank you,” I said, and took a tiny bite. Then, after a few minutes, another bite.

I had never eaten anything like that before, nor have I since. He didn’t know the extraordinary extent of my allergies. I didn’t know that he had received a James Beard award in the category of Best Chef Mid-Atlantic. I did not have a reaction. Luck. Terrines, I have since learned, frequently contain pistachios. There is no moral to this story.

This essay is adapted from “The Bad Patient,” part of Bodies of Truth: Personal Narratives on Illness, Disability, and Medicine, edited by Dinty W. Moore, Erin Murphy, and Renée K. Nicholson, forthcoming from the University of Nebraska Press in 2019.